- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

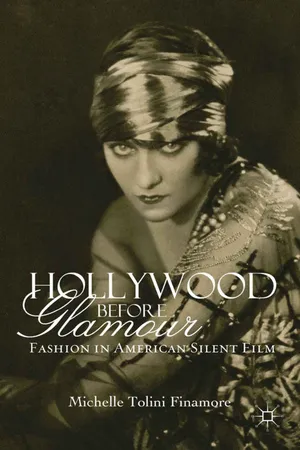

This exploration of fashion in American silent film offers fresh perspectives on the era preceding the studio system, and the evolution of Hollywood's distinctive brand of glamour. By the 1910s, the moving image was an integral part of everyday life and communicated fascinating, but as yet un-investigated, ideas and ideals about fashionable dress.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hollywood Before Glamour by M. Tolini Finamore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

In 1914, a young Gloria Swanson dressed up in her most fashionable ensemble to visit Essanay studios in Chicago. In her autobiography, Swanson recalled it was “one of the new Staten Island outfits [she] was dying to wear. It was a black-and-white checkered skirt with a slit in the front from an Irene Castle pattern and a black cutaway jacket with a green waistcoat. I wore a perky little Knox felt hat with it.”1 Her memory of this day was probably sparked by the photograph of the graphic ensemble that is tipped into one of the innumerable scrapbooks documenting her career (Figure 1.1). Swanson wrote in cursive above the picture: “Simple Sixteen and oh so chic.” Although she did not go to the studios to look for work, the casting director asked her to return the next day to play a role in a moving picture. Swanson told her aunt that she was certain her suit’s provenance – modeled after the clothing of famed dancer and fashion icon Irene Castle – was the real reason for his interest. The next day the casting director telephoned and requested that she wear the same outfit, proving her right.2

Before the establishment of well-stocked wardrobe departments with in-house costume designers, it was important for budding starlets, who usually wore their own clothing for films, to strike the right balance of fashionability, charisma, and potential on-screen presence. Swanson soon demonstrated that she was so astute at dressing herself that only five years into her career the press commented that she was “one of the best dressed women on the screen.” The same article also noted that her personal sense of style had undoubtedly bolstered her precipitous ascent to stardom.3 Indeed, one of her scrapbook pages from her later career had her handwritten inscription posted above various fashionable press shots and reading: “Proving the fact that Gloria is the best dressed woman both on and off the screen & Oh: Irene Castle”4 (Figure 1.2).

Swanson could not have known on that day at Essanay that she would become a wildly successful film actress who would soon displace Irene Castle as the epitome of chic. Swanson’s early career spans the time frame of this book and is a unifying thread that offers insight into the significant changes in the presentation, and representation, of fashion in American film in the first decades of the twentieth century. Between 1905 and 1925, the film industry evolved from a small-scale form of entertainment with working-class associations to a more refined product aimed at a broader audience that included the middle classes. The study begins in the incipient years of the US film industry, which was then only ten years old, and examines the emergence of what is now known as Hollywood’s “golden age” and the concomitant rise of a distinctive brand of Hollywood glamour. The 30-year period witnessed profound changes in audience, corporate organization, and approaches to design on film, all of which influenced how fashion was displayed to the viewer.

Figure 1.1 Gloria Swanson in outfit worn to visit Essanay Studios, Chicago, 1914. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Courtesy of Gloria Swanson Inc.

Figure 1.2 Page from Gloria Swanson’s scrapbook showing Swanson as fashion plate in various press clippings. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Courtesy of Gloria Swanson Inc.

It is commonly believed that film producers in the nascent days of cinema (1905–15) were not interested in fashion because actors were required to supply their own garments for film. There is, however, ample evidence that in those years conscious decisions were being made about dress and its screen presentation by actors, casting directors, directors, art directors, and uncredited designers, who were working in far greater numbers than has hitherto been recognized. From the mid-1910s on, ready-to-wear and high fashion were incorporated into film narratives and commercial “tie-ups” were established between the film and fashion industries. In addition, social messages related to dress were incorporated into the narrative content of films, reflecting broader cultural issues, including the moral reform movements of the Progressive era and a new interest in “American” design during World War I.

The star’s image, her clothing, and the film company’s desired trademark look were tightly intertwined. When Swanson signed her contract with Cecil B. DeMille in 1919, the very first clause in the agreement stipulated that the studio was in control of the star’s public image. The clause immediately following dealt with clothing and wardrobe, noting that the film company would furnish all the “costumes” and gowns for the starlet. The actor’s clothing was inextricably linked to his or her on-screen image. Furthermore, the distinction between “costumes” and gowns was an important one. “Costumes” referred to clothing for historical dramas or “character” parts, and “gowns” referred to contemporary clothing, which would often be purchased from fashion designers, custom salons, or department stores for, or by, the actress.

While the first in-house designers to be awarded regular on-screen credits were not hired until the late 1920s, there were many wardrobe heads and designers working “behind the scenes” in the 1910s. Swanson worked with one of the earliest-named costume designers in film – Clare West – who famously costumed Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1914) and was later employed to dress Cecil B. DeMille’s lavishly dressed pictures. Yet, the work of Jane Lewis, Alpharetta Hoffmann, Mme. Violet (a.k.a. Mrs. George Unholz), and Irene Duncan is today unappreciated because of lack of on-screen acknowledgment. Nevertheless, these designers too played an important role in the industry and in the interface between fashion and film.

For contemporary-dress pictures, stars like Swanson, with her substantial income, could patronize the premier fashion designers in both the United States and France. Swanson in particular was quite savvy about writing her clothing expenses into her contract and purchased garments from the finest makers available, including the custom shops at Bonwit Teller, Henri Bendel, and J. Thorpe, and couture designers such as Lucile.5 The international couturière Lucile (a.k.a. Lady Duff Gordon), who had a fashion salon on the East Coast, was a ubiquitous and influential presence on the screen (see Chapters 3 and 4). The life and work of West Coast costume designer and fashion editor Peggy Hamilton Adams also constitute a case study within this book, because her experience helps to illuminate the differences between a fashion designer like Lucile, who “dressed” films, and a costume designer working in the film industry, who designed garments specifically for film. As the industry grew and film producers shifted their interest to attracting a more middle-class audience, costume design became a more integral part of the film’s art direction and the production process and the line between “costumes” and gowns increasingly blurred.

In terms of film narrative, the audience was an important determinant of subject matter and Chapter 2, The Working Girl and the Fashionable Libertine: Fashion and Film in the Progressive Era, serves as a general introduction to the relationship between the fashion and film industries between 1905 and approximately 1914. It offers an overview of major developments in the fashion and film industries before 1914, and an investigation of how the cultural and moral values of the period informed film content. The chapter explores how a largely working-class audience saw actors costumed in “everyday” dress who played out roles in class-based narratives. These films ranged from those in which a factory worker is shown producing garments to those that highlight custom-made clothing only accessible to an upper-middle-class or upper-class consumer. A discussion of both fictional and documentary films produced in the United States that addressed garment manufacturing explores how fashion, specifically the shirtwaist, was presented to, and also reflected, the dress concerns of working-class audiences. The type of working girl depicted in the films studied in this chapter ranged from the shirtwaist factory worker and the mill girl to the at-home pieceworker. Some fictional shorts that illustrated working life were heavy on pathos, while others were part of a “social problem” genre that aimed to be conscious rallying cries for changes in labor laws. The infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, for example, was the subject of a number of films. Not only was there documentary coverage of the fire, but the plight of the factory girl entered the public consciousness through numerous fictional films that replicated and commented on the dire working conditions of sweatshops.

Although images of haute couture–inspired fashion in the newsreels were becoming more and more prevalent (and are explored in depth in Chapter 4), when high fashion was part of a storyline in the period 1905–14, it was often satirized and used to demonstrate how urban, Parisian design could turn a simple country girl into a “fashionable libertine” or a wanton woman. Chapter 2 also explores how the burlesque of common fashion trends such as the picture hat, the sheath or Directoire-style dress, and Orientalist Parisian couture was affected by the larger cultural context of moral reform. Such comedic send-ups of fashionable dress make sense within the context of what film historian Tom Gunning has termed the “cinema of attractions,” which still drew much inspiration from the Vaudeville stage and its slapstick routines. From the beginning of the “Nickelodeon” period (i.e., from 1907–12) to the late 1910s, a gradual shift occurred from films that emphasized the production of fashion, to those that emphasized the consumption of fashion.6

World War I was important to the evolution of the American film industry in general, and to the representation of fashion in particular. Chapter 3, “American” Design in Fashion and Film, explores how reduced exports from Europe during the war led to advances in both industries. In film, the era of World War I is considered seminal to the United States’ eventual domination of the global film market and the fashion world. The war compelled designers, magazine and newspaper editors, and others to look to home-grown talent and focus more attention on “American” design. The chapter will explore the notion of “Americanness” from various perspectives: through attitudes about the “immorality” of French fashion and film, in terms of actual design (some more literally “American” than others); through the notion that film and ready-to-wear fashion were truly “democratic” American arts; and via propaganda films. At the start of Swanson’s career, she was dressed by Peggy Hamilton at the short-lived Triangle Film Corporation for a number of these propaganda films, which she noted were common fare at the time. While some may argue that advances made by American fashion during the war were short-lived, film maintained its hegemonic control of the international market after the war ended.7

In addition to print media, fashion newsreels were becoming an important disseminator of up-to-date information about the latest fashions of the Paris couture industry. Chapter 4, Goddesses from the Machine: The Fashion Show on Film, explores the history of early fashion newsreels and considers their divergence from narrative films in the ways in which they treated high fashion. Production values in these newsreels followed the visual pattern seen in other film genres, evolving from unsophisticated and somewhat static presentations in the early 1900s to livelier and more refined showings of the latest offerings from Paris. Some of the earliest newsreels depicted mannequins revolving on turntables set against wrinkled, curtained backdrops. By the early 1910s, however, the fashion show had matured and the film stagings of fashion drew their inspiration from the private showings of couture houses, complete with eighteenth-century-inspired salon settings and professional “living” mannequins.

Lucile and Paul Poiret, both of whom were exceptionally skilled at marketing, were two of the first couture designers to exploit film for business promotion. Their involvement in film further popularized their couture houses and contributed to their name recognition in the United States. Lucile’s relationship with the industry was long-lasting and fruitful and she designed clothing for many more films than has commonly been documented. While both Poiret and Lucile claimed to have “invented” the fashion show, Lucile was more successful in applying her fashion-show innovations to film, and she dressed some of the characters in the earliest serial dramas. The fashion newsreels, together with melodramatic filmic narrative, evolved into a new category of fashion presentation – the stylishly dressed serial drama. Chapter 4 investigates these highly popular serial dramas in which the self-assured and physically active “new woman” heroine played out all manner of derring-do while wearing couture garments, and analyzes how these serials functioned as a type of runway show, with changes of dress within each episode and new clothing featured each week.

As Lucile was well aware, the film viewer was potentially an important consumer, but the focus of these films was on brand recognition rather than on providing information about how to purchase the garments featured on the screen. Newsreels of the early 1910s often highlighted the latest styles from Paris, without always crediting the designer. Although Lucile was often recognized in the contemporary press as the designer of numerous films, she often did not get billing in the screen credits. The industry was, however, beginning to experiment with the potential of commercial tie-ups and newspapers, local shops, and department stores, and the newsreel and serial drama were the first to exploit these connections. Fashion serials like Our Mutual Girl (1914), for example, were coupled with highly successful marketing campaigns.

Couture fashion directly from the Parisian runways gradually started to be more important to both film producers and actresses, some of whom were becoming recognized in their own right as “stars.” The term “star” was first used with reference to Florence Turner, the Vitagraph Girl, in 1910 and the “star system” gained in power from 1912 onward.8 Fan magazines, which were also on the rise, began to identify the Paris or New York designers of the stars’ on- and off-screen wardrobes. Fans grew to expect to see their favorite stars dressed in the latest styles and film marketers began to advertise not only the designers but also, when relevant, the impressive expense of costuming particular films. In terms of plot content, social problem films depicting the plight of the working classes were on the wane and films that venerated, rather than satirized, high fashion were on the rise. Many films continued to convey their moralistic messages, but even these provided a storyline that would allow for the insertion of a mise-en-scène that focused on the latest in fashionable dress.

By the late 1910s, the film industry’s focus on fashion and its consumption became even more intense, and themes that would “please the ladies” directly inspired the subject matter of film.9 Advances in the mass production of ready-t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Working Girl and the Fashionable Libertine: Fashion and Film in the Progressive Era

- 3 World War I and “American” Design in Fashion and Film

- 4 “Goddesses from the Machine”: The Fashion Show on Film

- 5 Costumes and Gowns: The Rise of the Specialist Film Costume Designer

- 6 Peggy Hamilton: Queen of Filmland Fashion

- 7 The Birth of Hollywood Glamour

- Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index