- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book discusses British cinema's representation of the Great War during the 1920s. It argues that popular cinematic representations of the war offered surviving audiences a language through which to interpret their recent experience, and traces the ways in which those interpretations changed during the decade.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Great War in Popular British Cinema of the 1920s by L. Napper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘In the Midst of Peace, We Are at War’: The British Film Trade in 1919

Even before the Armistice was signed, anxieties about the challenges faced by the cinema trade in the post-war period were already being expressed. There were concerns not only about the speed with which wartime restrictions might be lifted (an issue close to the hearts of exhibitors), but also questions about the cinematic representation of the war and the reception of such films by audiences with first-hand experience of the conflict (Figure 1.1). This chapter is intended to sketch out some of these debates briefly, particularly as they appeared in one of the leading trade magazines, Kinematograph Weekly. It offers a snapshot of the trade in 1919, detailing some of the difficulties involved in the transition to peace, but also establishing some of the more fundamental themes which would continue to concern the trade throughout the 1920s, not least its relationship with American cinema.

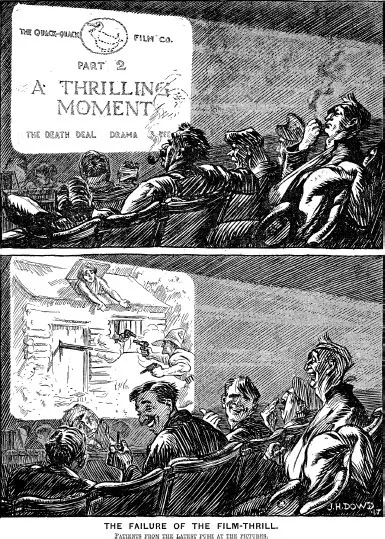

J.H. Dowd’s cartoon from Punch in August 1917 offers a useful starting point.1 It shows a number of veterans of the ‘latest push’ settling down to enjoy a picture in their local cinema. Their keen and serious anticipation turns to ridicule when the dissonance between their own authentic experience and the screen’s account of conflict is revealed. The cartoon clearly suggests that a shift in language is going to be necessary before cinema can seriously address a public with the particular investment of experience on the subject of the war. The cinema’s ability to connect spectators to the experience of serving soldiers had formed a key plank in the campaign for respectability by the industry during 1916 and for its recognition by the government as a vital part of the war and propaganda effort. The success of the officially sponsored feature-length documentary The Battle of the Somme (1916), not just in reaching the habitual cinemagoers of the working class, but also large numbers of middle-class spectators, was widely recognized. Thus, ‘authentic’ scenes of First World War battle were already central to a series of arguments about the ability of cinema to be a moral and ethical force for the good, which were being mobilized by the industry in its lobbying activities. While the film being ridiculed in Punch isn’t explicitly a war film, it promises ‘thrills’ around ‘death dealing’, and offers these in an explicitly generic fictional narrative. The key reason for its ‘failure’ with this audience seems to be its inauthenticity – the contrived nature of the ‘thrills’ that it offers. These contrivances include particularly the damsel in distress and the action star able single-handedly to vanquish numerous baddies with his two-fisted bravery. Paul Fussell has suggested that the hero who has agency over his own fate is one of the first literary casualties of the Great War. The trench experience of ‘chaos, bondage and frustration’ makes such a hero unconvincing, and in literature, Fussell claims he was generally replaced with a more modern ‘ironic’ central character. That claim can’t quite be made for British cinematic representations of the war in the 1920s, but it is nevertheless noticeable that British film-makers are often careful to authenticate their representations of heroism through recourse to named individuals (e.g. in the focus on Victoria Cross (VC) winners in the cycle of battle reconstruction films) or ‘authentic’ locations and actors (as for example in Dawn (Herbert Wilcox, 1928)). The more cavalier habits of American producers often drew negative comment. As late as 1927, a British exhibitor and ex-soldier wrote to Kinematograph Weekly objecting to the prevalence of films showing US stars apparently single-handedly winning the war, arguing that, ‘to those of us who know the facts of the war it is only nauseating. If the Hollywood heroes had done so much fighting in France as they do on the films, the war would not have lasted quite so long.’ His objections were rooted, like those represented by Dowd, in personal experience. ‘It is not pleasant for an exhibitor like myself who had the pleasure of seeing the doughboys arrive in the summer of 1918 to be so often viewing this stuff’, he concluded, ‘and it is time that the producers had a very broad hint to this effect’.2

Figure 1.1 ‘The Failure of the Film-Thrill’ by J.H. Dowd for Punch, 15 August 1917, pp.12–13 (Punch Ltd.)

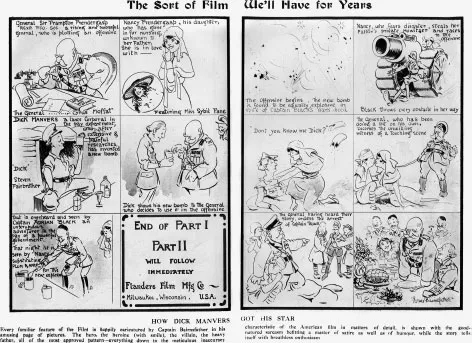

The timing of the Punch cartoon is perhaps significant. It appears in August 1917, only four months after America’s entry into the war, and about the time that Hollywood’s new output of war-themed films hit British cinemas. Another cartoon from around this time is more explicit. Bruce Bairnsfather’s spoof of an American war picture in Fragments from France is made by the ‘Flanders Film Manufacturing Company’, which is identified as being based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA.3 The caption draws attention to ‘the meticulous inaccuracy characteristic of American film in matters of detail’, while the generic characteristics of such films are parodied. The hero with agency and the plucky heroine at the front are rolled together into ‘Nancy Prendergasp’, who rushes into the theatre of war to save her beau from death, much as Clara Bow would do a decade later in the Oscar-winning Wings (William Wellman, 1927), confirming Bairnsfather’s suspicion that this is ‘The Sort of Film We’ll Have for Years’.

What in 1917 was a subject for ‘good natured sarcasm’ had become, by the end of the war, the object of quite serious concern in British film industry circles, as a range of discussions and reviews in Kinematograph Weekly attest (Figure 1.2). During the conflict, there had been a boom in the British exhibition industry, which had benefited from the increased spending power of a civilian population enjoying full employment in the wartime economy. As one writer put it, ‘much of the money made by munition workers has flowed into the coffers of the Kinema manager’.4 However, it had also been a period during which American film producers had consolidated their dominance of the market. Most films shown in British cinemas were American by 1918, and increasingly this was seen as a potential problem for the post-war industry – both economically and in terms of its reputation.

Reflecting in its Armistice week edition, the magazine concluded that during the war the industry had ‘played one of the most valuable parts in the national scheme of propaganda and education’ and that

a feeling of pride is permissible that the industry should not only have triumphed over its enemies, but have compelled recognition of its position as one of the most powerful factors of the day. At the end of the war it enjoys a status infinitely higher than it had at the beginning and its powers for the future are recognized thankfully or grudgingly, by every class of the community.5

Nevertheless, the paper warned, the process of transferring the trade from war to peacetime operations ‘bristles with difficulties’ and its readers should not be surprised to find ‘Peace a more testing time than War’ in the first instance.6 Over the coming months, the magazine identified a variety of specific difficulties facing the trade. Some of these were relatively specific to the immediate transition period. Discussion on the speed of the relaxation of wartime restrictions on lighting and fuel and cinema building for instance, was relatively short lived, although the Entertainments Tax introduced in 1916 remained a thorn in exhibitors’ sides for many years to come.7 A more complex question concerned the speed of the repatriation of ex-servicemen and their re-integration into the industry, an issue highlighted by the plight of returning projectionists, as described below. Finally, anxieties about the prospect of a German trade invasion, about continued pressure from government to screen ‘propaganda’ and about American film dominance were all couched in language which emphasized the idea that each of these developments posed a threat to the hard-won trust built up between the cinema and its patrons during the war years.

Figure 1.2 ‘The Sort of Film We’ll Have for Years’ by Bruce Bairnsfather in Still More Bystander Fragments from France, No. 3, The Bystander, 1916, pp. 12–13 (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Returning ex-servicemen

Arguing for permanent establishment of the wartime ‘Trades Benevolent Fund’, Kinematograph Weekly observed that managers owed a ‘debt of gratitude’ to those who had left jobs in cinemas to serve in the war and that such figures had a ‘right of preference’ to all new job openings which may occur with the predicted expansion of the trade in the immediate post-war period. These were rights which returning men could rely on, the paper intimated, but in addition to this, the Trades Benevolent Fund had a duty to ‘see that the maimed and invalid soldier does not suffer more than the inevitable penalty of his disability’.8 How such an object might be achieved was suggested by an article which had appeared in the magazine only three days before the Armistice. ‘How the Kinema Industry Is Helping Our Disabled Men’ gave details of a scheme which had been running since 1916, called the ‘Cinematograph Training and Employment Bureau’. The scheme was based in Wardour Street, and headed by a Captain Paul Kimberley with the co-operation of the Ministry of Labour and the Ministry of Pensions.

The object of the scheme was to train disabled ex-servicemen as cinema projectionists. The article details the rigorous stages of the training – from film handling, to electrical and motor engineering, to health and safety issues, to the use of arc lamps, to the final projection of a film in a West End cinema under professional conditions. In the two years the scheme had been running, 32 men had been trained, and armed with a ‘Government certificate as a fully qualified kinema operator’, had found employment. Kinematograph Weekly had nothing but praise for their skill and for the scheme as a whole, arguing that it would

give lasting benefit to the heroes who have risked their lives in defense of our homeland. One cannot imagine anything fairer than to give these boys a fresh start, a new incentive, to make them realize that life can still be worth while, and that there is something to strive for and attain.9

However, while the paper supported the scheme energetically in the autumn of 1918 and carried several reports of other schemes with a similar objective, by the following spring, it seems to have completely reversed its position.10

With the end of the war and the demobilization of many ex-projectionists, pressure started to build for a professional organization to protect their interests. Alarm was expressed that the ‘projectionists of 1914’ were returning to find their places had been filled for the duration by inexperienced women and youths, and that managers were unwilling to re-employ them since their substitutes demanded less wages.11 The paper expressed its outrage at such practices, arguing that any manager who

indulges in or supports the employment of women because they are cheaper and more easily disciplined than men is as much a menace to the industry as any other species of undercutter.12

The proposed solution had two inter-related elements. Firstly, the argument was made that, like the disabled graduates of the Cinematograph Training and Employment Bureau, all projectionists seeking work should be required to supply a certificate of proficiency. P.F. Morgan made the comparison between a projectionist and a motorcar driver. A driver needed a licence of proficiency because incompetent handling of a car could result in death. So too did a projectionist in whose hands were entrusted the safety of large audiences – a poor projectionist with inadequate safety awareness could easily cause a fire which would endanger life in the same way as a poor motorist could.13 Secondly, the magazine recommended the formation of a projectionists’ union to administer the licence and to ensure that no operator without the adequate training would be employed.14 In trenchant terms, W.A. Waldie (who had already formed a prototype union in the North of England) argued that such a system was necessary, because,

There are plenty of men coming from the Army who should be given the first chance, and both boys and female operators should be eliminated.15

What, then, of the disabled ex-servicemen who were, after all, new to the trade, and had been trained up precisely to fill the labour shortage created by the war? Commentators considered their training to be a model for the future, suggesting that the examination they were subject to should be applied nationally. As men who had ‘served their country’, their claim was greater than that of the ‘women and youths’:

There is not the slightest need to turn a single trained soldier-operator adrift in order to find work for the returning operators. There are about four thousand picture theatres in this country, and if out of that number two hundred positions cannot be reserved for the two hundred disabled men who have been specially trained in order to enter the Industry, then something is wrong somewhere.16

This argument was made in the context of the establishment of the ‘King’s Fund’ which had been set up by John Hodge MP of the Pensions Ministry. It was a charitable body organized to award grants to disabled ex-servicemen in order to enable them to undergo training or start businesses suited to their physical needs. The cinema had been instrumental in publicizing the fund, with Hodge himself appearing in a fundraising film Broken in the Wars by Cecil Hepworth – a drama starring Chrissie White and Henry Edwards as a disabled veteran who had benefited from the fund. To advertise such a scheme by showing the film, and yet not to act on it in their own business, it was argued, would ‘certainly bring a lasting disgrace on the whole industry’.17

This seemed like a powerful argument, but within three months, the magazine had performed its startling volte-face:

From time to time, we receive large numbers of letters from men, some discharged through disablement … enquiring the best means of obtaining a course of instruction to enable them to become operators. There have been schemes for this purpose in several parts of the country, but we do not think that many of the centres continue to accept pupils. Our advice to those desirous of undergoing a course of training for the purpose of becoming operators is the same as the famous advice of Punch on the question of marriage – Don’t!18

Defending itself in following weeks against the accusation by the Chairman of the Yorkshire Disablement Committee that the trade had abandoned its interest in the wounded and discharged soldier, the paper stoutly maintained that precisely the opposite was the case. It was because priority had been given to ex-servicemen returning to their old jobs – the ‘men of 1914’ – that there were no jobs available for disabled but newly trained men.19 While a projectionists’ union did indeed result from these struggles of 1919, the fate of the scheme for training disabled ex-servicemen is only too typical of the treatm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Peace Days in Pictureland

- 1. ‘In the Midst of Peace, We Are at War’: The British Film Trade in 1919

- 2. Battle Reconstructions and British Instructional Films

- 3. Remembrance and the Ambivalent Gaze

- 4. ‘When the Boys Come Home’

- Conclusion: Tell England

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index