eBook - ePub

Vulnerabilities, Impacts, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Vulnerabilities, Impacts, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

About this book

This book examines HIV/AIDS vulnerabilities, impacts and responses in the socioeconomic and cultural context of Sub-Saharan Africa. With contributions from social scientists and public health experts, the volume identifies gender inequality and poverty as the main causes of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vulnerabilities, Impacts, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa by Getnet Tadele,Helmut Kloos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Contextualizing HIV/AIDS

1

Introduction

We are now approaching four decades since AIDS was first reported from Africa and yet, notwithstanding tremendous progress during the last decade, we are far from containing the pandemic caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In 2010, an estimated 68% of all people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and 70% of all new infections were in Sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS 2011, p. 7). Even though 22 countries in this region reported declines in HIV incidence of 25% or more and 20% fewer people died in 2009 than in 2001, the total number of PLWHA in Sub-Saharan Africa increased by 2.2 million during that period, 1.5 million of which lived in southern Africa, the most highly affected region. South Africa, the country with the largest epidemic worldwide, reported 220,000 AIDS-related deaths in 2001 and 310,000 in 2009; 15 other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa reported smaller increases in mortality although a downward trend appeared in the region after 2004 as a result of intensified interventions (UNAIDS 2010, pp. 16, 180, 185). AIDS continues to severely impact households, communities, businesses, public services, and national economies in the Sub-Saharan African region and local, national, and international stakeholders searching for new, effective, and sustainable ways to contain the epidemic.

Recognizing that HIV/AIDS is a social, behavioral, and biomedical problem requires that socioeconomic, cultural, and political factors be carefully examined toward unraveling this complex phenomenon in Africa. Our understanding of the historical, social, economic, cultural, and political contexts of the disease and of human sexuality, which accounts more than any other factor for the transmission of the virus in Sub-Saharan Africa, is paramount to the development of effective prevention and control programs (Kalipeni et al. 2004). Toward achieving that understanding, this book examines how the web of socioeconomic factors and cultural norms surrounding sexuality and stigma influences the trajectory of HIV and AIDS and identifies both persisting and emerging challenges and opportunities for HIV prevention and control and care and support for AIDS patients in Sub-Saharan Africa. From a social science perspective, it extensively frames how broader structural issues such as religion, culture, gender, food insecurity, masculinity, and other socioeconomic factors influence transmission, prevention, care, and treatment of HIV/AIDS. This book strongly argues that placing HIV/AIDS within the broader social, cultural, economic, and political context of the region goes a long way toward an appropriate understanding of the dynamics of the epidemic and the development of effective, contextual, and multisectoral strategies and programs aimed at not only halting and ultimately reducing the spread of the epidemic, but also devising ways of addressing its enormous social, economic, demographic, and institutional consequences.

Mapping the context: the epidemic in historical and spatial perspectives

Historical perspective

Emerging in the late 1970s and reaching epidemic proportions in the early 1980s, HIV could not have come at a worse time to Africa. Much of Sub-Saharan Africa was in crisis either because of war, famine, bad governance, and coups or structural adjustment programs that forced governments to cut spending on social services. Of the 19 major famines in the world between 1975 and 1990, 18 occurred in Africa, and more than half of all African countries experienced military conflicts from the 1980s on, leading to the displacement of more than 10 million people and sharp declines in food production (Caraël 2006). The economies of those countries were, as a result, ill prepared to deal with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Adding to the problem, the structural adjustment programs of the 1970s and 1980s had devastating effects on social sectors such as education and health, leaving them unable to respond to the emerging epidemic (Caraël 2006; Farmer 1999; Nattrass 2004; Seckinelgin 2008).

Conflicts, famines, and economic crises were not, however, the only reasons the epidemic spread rapidly over the continent in its early stages. In much of Africa, leaders were often reluctant to acknowledge the very presence of HIV/AIDS or the danger it caused during its initial phase (1984–1988). A disease that was associated in the affluent countries of the West with homosexual behavior, prostitution, and intravenous drug usage seemed, at the time, impossible in Africa. Even when its presence was acknowledged, AIDS was seen as a foreign disease spread on the continent by white homosexuals, or as an elaborate conspiracy by the West aimed at bringing down the birth rate of Africans by imposing the use of condoms, or as an attack against African traditions such as polygamy (Caraël 2006; Farmer 1993, cited in Seckinelgin 2008). In some countries of the region, such thinking led to the denial of the disease at the highest political levels. President Mobutu of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), for example, banned the subject of HIV/AIDS from the press between 1983 and 1987. Government warnings in the 1980s and early 1990s that AIDS kills and that it is incurable intensified the confusion, discrimination, and blaming that surrounded the condition (Iliffe 2006, pp. 81–86). The situation was worsened by the apparent (although short-lived) hesitation of the industrialized countries to accept the seriousness of HIV/AIDS. This was perhaps best epitomized by the now infamous 1985 comment of the then Director General of WHO that tropical diseases such as malaria were in danger of being neglected because of HIV/AIDS (Iliffe 2006, p. 68).

As world leaders began to realize that HIV/AIDS could not be simply denied as a mythical construct or an elaborate conspiracy of the West or dismissed as less important than other challenges facing African nations, prevention campaigns slowly swung into action in many Sub-Saharan African countries. But these were largely ineffective in curtailing the spread of the epidemic. The international community was yet to take decisive action, and many national government programs were underfunded, corrupt, or otherwise ill equipped to deal with the escalating crisis. It took the world until 1996 to establish UNAIDS (The United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS) as the responsible body for coordinating actions worldwide against the pandemic. But by then the seriousness of the epidemic was blatantly clear to even the most hardened skeptics and some countries, including Kenya, had already declared AIDS a national disaster (AFP 1999).

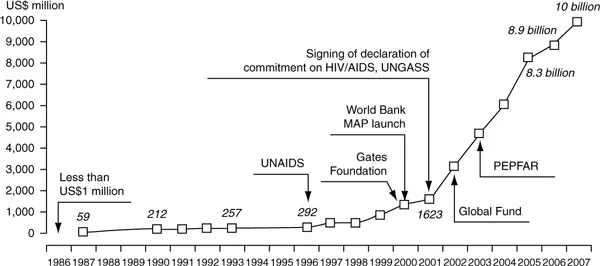

At the turn of the new millennium, the international effort to fight HIV/AIDS gained momentum. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria was created in 2001 following a special meeting of the UN General Assembly called to discuss HIV/AIDS. United States President George W. Bush announced the establishment of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) two years later. Overall global funding for HIV/AIDS increased threefold between 2002 and 2007, when it reached $10 billion (Figure 1.1). Funding rose to $15.9 billion in 2009 but fell to $15 billion in 2010 (Sidibe 2011).

Sub-Saharan Africa has received about half of all international AIDS spending in recent years and 54.2% from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in 2009, the major distributor of HIV/AIDS funds (Salaam-Blyther 2010). This fact, together with the actions of governments to strengthen health services, issue guidelines, and launch initiatives facilitating treatment activities, especially in rural areas, yielded positive results almost immediately. Between 2003 and 2009, the number of people receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV/AIDS in eastern and southern Africa increased from fewer than 100,000 to 3.1 million. Treatment coverage was particularly high in these two regions, where national rates between 55% and 67% were reported for females and rates between 31% and 45% for males in 2009 (UNAIDS 2010, p. 256). Although the full impact of the stepped-up intervention remains to be determined, HIV prevalence has declined in Sub-Saharan African countries since the late 1990s, when the number of new HIV infections peaked in much of the region (UNAIDS 2010, p. 27).

Figure 1.1 Total annual funds made available for HIV/AIDS programs, 1986–2007

Notes: [1] 1986–2000 figures are for international funds only

[2] Domestic funds are included from 2001 onwards

[i] 1996–2005 data: Extracted from 2006 Reported on the Global AIDS Epidemic (UNAIDS 2006)

[ii] 1986–1993 data: Mann & Tarantola (1996)

Source: UNAIDS (2008, p. 188).

But the increasing involvement of international actors brought a new complication to HIV/AIDS governance in Africa. There is now a well-established global governance of HIV/AIDS, which, while providing the much needed resource base for interventions, does not adequately reflect the way local people perceive, experience, and respond to the disease within their sociocultural and economic contexts. As a result, researchers have questioned the appropriateness of international governance of HIV/AIDS to deal with the prevailing issues in a multiplicity of contexts across Africa (Seckinelgin 2008; see also Tamale 2011a). There is also a danger in relying on HIV/AIDS-related funding to bring about the multifaceted socio-economic structural transformations (such as universal education, economic opportunities for women, social protection systems, and support for the agricultural sector) that are required to bring about and sustain a meaningful and viable local capacity to challenge the threat posed by HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS 2008).

The Global Fund jeopardized the progress made in preventing HIV/AIDS and increasing the number of people on ART when it cancelled Round 11 of funding in 2011 because of dwindling resources. Most HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (TB) programs in Africa are financed by the Global Fund, and reduced funding may endanger the gains made in the fight against HIV/AIDS so far-Though this new development is worrisome for Africa, it may provide an opportunity for African governments to mobilize domestic resources and take ownership of the HIV/AIDS response. Moreover, the mobilization of activists and health care consumers has pressured global and national leaders toward a stronger sense of accountability and urgency, and a number of innovative preventive and health services approaches, as well as greater participation of the private sector in Sub-Saharan Africa promise to render HIV/AIDS programs more cost-effective and sustainable (Berhe 2011; Idoko and Bequele 2011; Traore 2011).

Spatial aspects

The increased testing of general populations and improvements in the reliability of HIV prevalence data have enabled planners to better understand the geographic distribution of HIV infections. The pattern that is emerging from recent national sample surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa indicates that several countries have concentrated epidemics, usually in urban areas that are characterized by sharply higher prevalence of infection in vulnerable groups than in the general population. The heterogeneous distribution of HIV infection in all countries, not only in those with concentrated epidemics affecting mostly high-risk groups but also those with generalized epidemics, demands that interventions be well designed and adequate resources allocated to highly infected high-risk groups (Forsythe et al. 2009). Furthermore, the uneven HIV distributions can give only a general indication of the real prevalence and total number of people infected in individual countries (Forsythe et al. 2009) but not of regional differences.

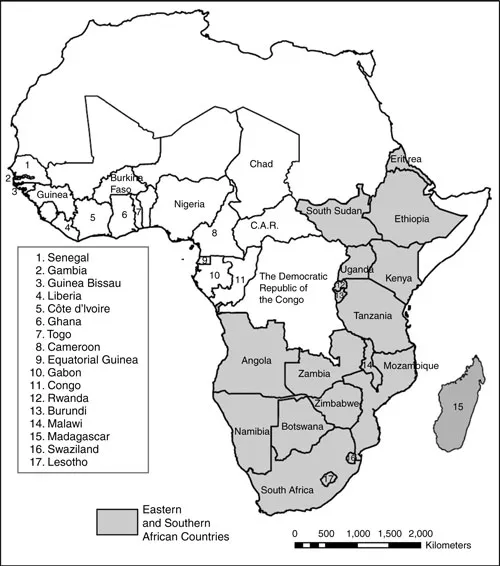

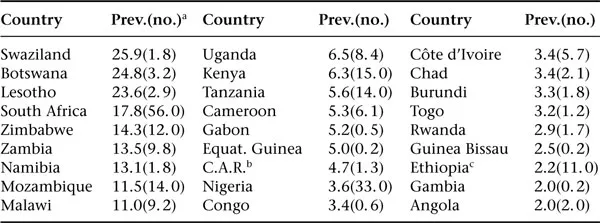

Nine of the ten countries in continental Southern Africa had HIV prevalence rates among 15- to 49-year-olds between 11% and 25.9%, the highest worldwide, and five countries in eastern Africa (Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Burundi, and Rwanda) and eleven countries in Central and West Africa (Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Central African Republic, Gabon, Nigeria, Togo, Guinea Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Congo, Chad, and Gambia) reported rates between 2% and 5.3% (Figure 1.2 and Table 1.1). Swaziland, with an estimated HIV prevalence rate of 25.9% among adults aged 15–49 in 2009, had the highest infection rate in the world, and South Africa had the largest population living with HIV, about 5.6 million. The most populous countries in eastern Africa (Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Kenya) had larger HIV-infected populations than Nigeria and all but three countries in southern Africa (South Africa, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe) in spite of relatively low HIV prevalence rates (Table 1.1). HIV rate in Madagascar was only 0.2% in 2009, the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa, apparently due to the island’s geographic and political isolation, but lack of data for high-risk groups and recent social instability render available data questionable. Little information is also available for Somalia and the newly independent South Sudan, both of which were brutalized by civil war, although rates are thought to be low (Ahmed 2011). This information is consistent with the relatively low HIV prevalence reported from Angola (2%), another war-ravaged country. These figures contradict the common assumption at the turn of the millennium that armed conflict significantly fuelled the epidemic; this assumption diverted attention from the major driving forces of the epidemic, identified by de Waal (2010) and Kalipeni et al. (2004) as gender and socioeconomic inequities, stigma, and discrimination.

Figure 1.2 Sub-Saharan Africa, eastern and southern subregions (shaded) and the countries in Central and West Africa referenced in the text (white), with names and numbers

Although we examine studies and data from nearly all Sub-Saharan African countries (Figure 1.2), the focus is on the eastern and southern subregions mainly because they are impacted most severely by the epidemic and are the focus of most research on HIV/AIDS published in the English language. These regions have additional importance as high HIV impact areas because of the regional distribution of the two strains of HIV.

Table 1.1 HIV prevalence (%) among children and adults and the number of infected adults (15- to 49-year-olds) in Sub-Saharan African countries with rates of 2% and higher in 2009

ain 100,000s.

bCentral African Republic.

cThe data for Ethiopia are for 2007.

Sources: Based on UNAIDS (2010, pp. 180, 181) and Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) (2010).

Whereas HIV1, more easily transmitted and more virulent than HIV2, is the only strain in eastern and southern Africa, both strains are endemic in Central and West Africa (Levy 2007, p. 7), possibly accounting for the lower HIV and AIDS rates in the latter two regions (Oppong and Agyei-Mensah 2004). Differences in HIV infection and risk behavior, as well as increasing ART and other interventions reported from eastern and southern Africa as well as Central Western Africa must be better understood (WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF 2011). This volume contributes to a better understanding of the vulnerabilities, impacts, and interventions at the regional level within the context of the multitude of contexts in which HIV occurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Our focus on the eastern and southern subregions allows for pertinent discussions of the management and governance of the epidemic in the most affected areas.

Counting the toll of the epidemic

As pointed out above, the most devastating impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic has been in eastern and southern Africa. In some Southern African countries, infection rates increased from 4% to 20% or more in adult populations in the 1990s. Moreover, although the cumulative number of AIDS patients has been decreasing in the last five years, the social and economic impacts of the epidemic remains at high levels and may even increase in some populations (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Demographic impact

While HIV prevalence declined in most countries between 2001 and 2009 and the rapid ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Part I: Contextualizing HIV/AIDS

- Part II: Impacts and Responses to HIV/AIDS

- Index