eBook - ePub

Economic Crisis in Europe

What it means for the EU and Russia

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Crisis in Europe

What it means for the EU and Russia

About this book

The financial crisis of 2008-09 took an unexpected turn upon challenging a core symbol of Europe's integration project, the Euro. In this volume, leading experts tackle questions on the capacity of the EU to respond, the manner discontent electorates will hold their leaders to account, and the implications for Europe's future relations with Russia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic Crisis in Europe by J. DeBardeleben, C. Viju, J. DeBardeleben,C. Viju in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Economic Crisis in the European Union

1

Macroeconomic Impacts of the 2008–09 Crisis in Europe

András Inotai

Although the European Union (EU) was not the source of the global financial and economic crisis that commenced in 2008, that crisis had consequences that spurred the 2011 Eurozone sovereign debt problems. Europe, at the time of this writing, is still engaged in faltering efforts to stabilize its own economic and monetary situation, and it remains unclear, as of early 2012, whether those initiatives will produce a resolution or merely be one more step in a series of global economic upheavals that will require a fundamental rewriting of the international financial and economic relationships.

The 2008–09 crisis consisted of four interrelated stages that followed on from one to another with a certain time lag: financial, macroeconomic, social, and mental–ideological. Adverse social developments, taking the form of persistently high levels of unemployment, rising poverty, increasing income differentiation, and cutbacks in welfare provision, began to manifest themselves visibly in 2011, even as European countries showed unconvincing signs of recovery. Ideological and leadership crisis may be the fourth stage, and signs can already be observed in some member countries. This stage of the crisis relates to the apparently deep-rooted (protracted, still hidden) incapacity of states to remedy the impacts of the crisis and was already visible in the United States’ political deadlock over how to deal with rising debts and deficits in mid-2011, showing signs of taking on a mass character in ‘Occupy Wall Street’ spin-offs that spread to Europe later that year. Meanwhile, European political leaders struggled to achieve a renewed or rewritten ‘balance’ between economic, political, social, cultural, and environmental concerns, on the one hand, and between national, EU-level, and global governance, on the other.

This chapter has a modest goal, namely to outline the macroeconomic impact of the 2008–09 crisis across the EU and in the Russian Federation, drawing on key comparative data. This data reveals the manner in which the developments of those years lay the groundwork for fundamental economic challenges that were to unfold for Europe so vividly in 2011, when sovereign debt levels in Greece (and possible contagion effects in other Eurozone countries) set the stage for the next chapter in this global economic saga, threatening to throw the global economy into a repeat tailspin. As the narrative and data that follows will demonstrate, the impact of the 2008–09 crisis varied substantially across EU Member State countries. Moreover, an examination of data provided for the Russian Federation indicates substantial differences in the effects of the world crisis on Russia and the EU. As the subsequent two chapters in this volume indicate, these impacts raised fundamental challenges not only at the national level but also for the whole European integration project.

The crisis and macroeconomic performance of EU Member States and Russia

Based on international statistical data,1 we draw attention to six areas of macroeconomic impact: growth in gross domestic product (GDP), unemployment levels, budget deficits, public debt, international trade, and foreign direct investments.

Economic growth

In 2008–09, European growth rates experienced their sharpest declines in post-1945 history. From 2008 to 2009, global growth rates fell by just 0.5 per cent, made up of an average decline of 3.4 per cent in developed countries and average growth by 2.7 per cent in developing countries. Both the EU and Russia experienced a sharp decline in economic growth in 2009: 4.2 and 7.8 per cent, respectively (Table 1.1). For the first time since the Second World War, the crisis hit the developed countries harder, and its particular negative impact was felt in key growth-determining sectors of the economy (cars, electronics, construction). Also, the recession was accompanied by a severe downturn in international trade. In previous recessionary periods, foreign trade served as a mitigating factor, while during economic upswings it had previously proven to be a decisive driver of economic growth. Since most EU economies (not only the smaller ones but also some large ones, including Germany) are heavily reliant on international trade, the collapse of trade was bound to accelerate the downturn of GDP. In addition, in some EU Member States home-made problems, due to bad or misguided policies, further exacerbated the decline.

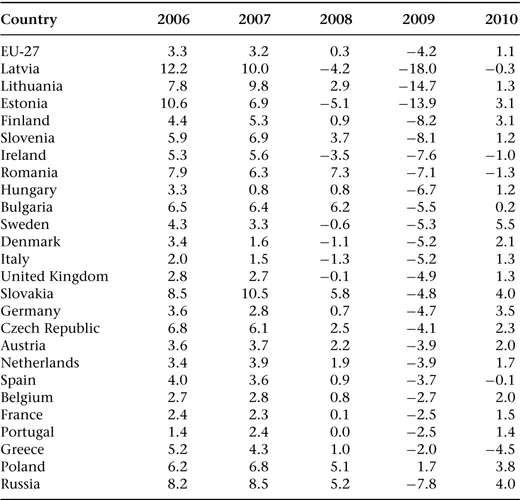

Table 1.1 Annual growth rate in the EU-27, selected EU Member States and Russia (2006–10, in per cent)

Source: IMF (2011) World Economic Outlook April 2011 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

In Table 1.1, the EU countries are classified according to their GDP decline, ordered by GDP decline in 2011. The largest GDP decline was registered in the three Baltic countries. The large drop in GDP can be explained not only by the international crisis but also by domestic mismanagement and a crucial lack of genuine transformation in the previous decade(s). The GDP decline in most of the other EU countries was a result of a combination of factors, such as mistaken economic policies, export vulnerability, and structural problems. The only EU member country with a positive growth rate was Poland, which was due to several, partly rather specific, factors that cannot be analysed here in detail.2

Russia, due to its heavy dependence on gas and oil exports, registered an abrupt decline of 7.8 per cent as a result of the collapse of world prices for these products. However, Russia’s inability to conduct proper economic reforms as well as its reluctance to weaken government control over key economic sectors remained the major impedements on its way to overcome the recession in 2010 (Cooper, 2009).

More important than these summary figures is an examination of the trend before and after the 2008–09 slump. Striking is the fact that this unique recession followed a no less unique high-growth period experienced by the EU in general, but particularly by several Member States in the period preceding 2008. The Baltic countries, which experienced the deepest dip in 2008–09, had also reported two-digit, or almost two-digit, growth rates in 2006 and 2007. In fact, all of the Central and East European new Member States, except Hungary, excelled with surprisingly high-growth rates in the pre-crisis period. Some EU Member States entered a negative growth period already in 2008, due to substantial internal and external imbalances (Latvia and Estonia most notably) and due to the impact of the banking crisis (here mainly Ireland and partly the United Kingdom). Also, the structural and competitiveness problems of the Mediterranean members of the EU became manifest in either stagnating (Portugal), negative (Italy) or remarkably declining growth rates (Spain and Greece).

The year 2010 proved to mark the beginning of an apparent, but very slow, return to ‘normality’ on the EU-27 level, but by far not in all Member States. Some countries continued to register negative growth rates (Romania, Spain, Ireland, Latvia), and, for several reasons, the recession kept on deepening in Greece. Most importantly, Greece’s sluggish recovery in 2010 was not strong enough to iron out the sharp fall of GDP in 2009. While the GDP of the United States returned to its 2008 level in 2010, the EU lagged behind. At least ten members will require more than three years to achieve the pre-crisis (2008) level of GDP (Inotai, 2011a). The Eurozone crisis, which followed on the 2008–09 financial and economic crisis, has complicated the recovery, making these estimates open to change. At the same time, Russia partially recovered in 2010, recording a growth rate of 4 per cent.

Table 1.2 presents two comparisons, a method to be followed in subsequent tables as well. One indicates levels for 2010, with 2007 as the base year (2007 = 100), recognizing the fact that this was the last year without any impact of the global crisis. The second is based on a more conventional comparison, by using 2008 as the reference year, the first ‘genuine’ initial year of the crisis. Several conclusions can be drawn from the statistical figures. While most countries reveal a larger slump between 2008 and 2010, due to their still increasing GDP in 2007, some Member States experienced a larger gap between the GDP-measured performance in 2007 and 2010. (This difference is indicated by lower figures comparing 2010 and 2007 data than with 2008 figures.) Between 2007 and 2010, four countries suffered a growth decline of more than 10 per cent (Latvia by more than 20 per cent). Russia along with six EU countries reached, or outperformed, their 2007 level of performance by 2010. Among the six countries reaching or overcoming the 2007 GDP level in 2010 are four new Member States (Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic).

Table 1.2 Depth of GDP decline as compared to pre-crisis levels in the EU, selected EU Member States and Russia (base years 2007 and 2008, respectively = 100)

Country | 2010–2007* | 2010–2008** |

EU | ||

Latvia | 78.3 | 81.8 |

Estonia | 84.2 | 88.8 |

Ireland | 88.3 | 91.5 |

Lithuania | 88.9 | 86.4 |

Greece | 94.5 | 93.6 |

Italy | 94.8 | 96.0 |

Hungary | 95.2 | 94.4 |

Finland | 95.5 | 94.6 |

Denmark | 95.7 | 96.8 |

United Kingdom | 96.2 | 96.3 |

Slovenia | 96.4 | 93.0 |

Spain | 97.1 | 96.2 |

Romania | 98.4 | 91.7 |

Portugal | 98.9 | 96.1 |

France | 99.1 | 99.0 |

Germany | 99.3 | 98.6 |

Sweden | 99.3 | 99.9 |

Netherlands | 99.6 | 97.7 |

Belgium | 100.0 | 99.2 |

Austria | 100.2 | 98.0 |

Bulgaria | 100.6 | 94.7 |

Czech Republic | 100.6 | 98.1 |

Slovakia | 104.8 | 99.0 |

Poland | 110.9 | 105.6 |

Russia | 114.0 | 89.2 |

*considering 2007 as the last full pre-crisis year.

**considering 2008 as the pre-crisis year.

Source: Own calculations based on IMF (2011) World Economic Outlook April 2011 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Unemployment

Most EU countries that were able and ready to introduce some kind of stimulus package in order to counteract the negative consequences of the crisis considered the stabilization of the labour market a key priority. In the framework of overall damage control, the remedying of short-term labour market and social consequences of the crisis enjoyed special attention. Still, as expected, in the majority of the EU Member States as well as in Russia, unemployment started to grow once the GDP decline seemed to have bottomed out and is likely to remain on the same high level even in the face of a modest recovery.

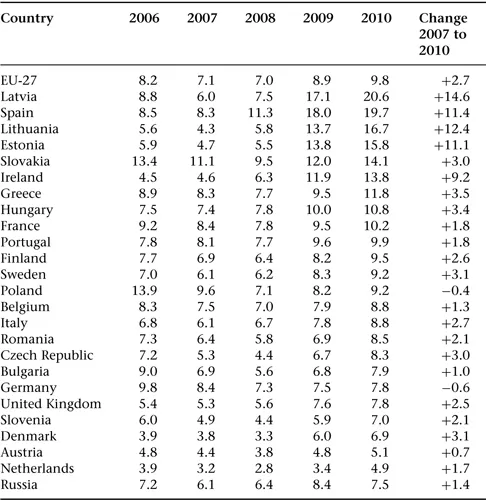

As Table 1.3 shows, for the EU-27 the average unemployment rate rose from 8.9 in 2009 to 9.8 per cent in 2010, and is expected to remain practically at the same level in 2011 (9.7 per cent). In 2010, nine countries reported two-digit unemployment figures, headed by Latvia and Spain with more or slightly less than 20 per cent. In Russia, the figures for unemployment increased by 1.4 percentage points, rising from 6.1 per cent in 2007 to 7.5 per cent in 2010, however, reaching the highest point of 8.4 per cent in 2009.

A more important aspect is the dynamic of unemployment as a consequence of the crisis. Between 2007 and 2010 the EU average unemployment rate rose by 2.7 percentage points, from 7.1 to almost 10 per cent. In some countries, the rise occurred from a relatively high level of pre-crisis unemployment, while in other countries relatively lower pre-crisis unemployment rates skyrocketed to the double-digit figures. The three Baltic countries, as well as Spain and Ireland, experienced the most dramatic increases in unemployment, with the rise registering from 9 to almost 15 per cent between 2007 and 2010. Registered unemployment figures rose almost everywhere (by 1–3 percentage points from country to country). While several member countries registered declining unemployment rates before the crisis, unemployment started to increase spectacularly as a result of the crisis between 2008 and 2010. Germany was, however, an exception that could successfully manage labour market constraints. Germany reduced its unemployment rate before the crisis (from 2007 to 2008) and instituted a massive anti-crisis policy mainly aimed at the labour market (and at the car industry), an important component being supported by a system of part-time work.3 By contrast, Poland substantially reduced the official unemployment rate from 2007 to 2008, in significant part due to large-scale emigration of Polish citizens (employees) to several other EU member countries. The crisis generated a rapid increase in the unemployment figure by 2010 (although not yet reaching the 2007 level) due to the back flow of workers from crisis-ridden Western European countries; these returnees could not be fully absorbed by the crisis-resistant domestic demand and growth (OECD, 2011).

Table 1.3 Unemployment rate in selected EU-27 Member States and Russia (in per cent of registered labour force)

Sources: Eurostat (2011a), IMF (2011) World Economic Outlook April 2011 (Washington: International Monetary Fund) and own calculations (last column).

Budget deficits

The development of budget deficits (see Table 1.4) is important for two reasons. First, these deficits quantify the (short-term) budgetary impact of anti-crisis measures. Second, budget deficits are one of the key Maastricht criteria that should be met by the Eurozone member countries in general and by applicant countries to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in particular. In fact, in the last pre-crisis year (2007), almost all EMU members (except Greece) and almost all applicants preparing for EMU membership (except Hungary) were within the limits set by the Maastricht rules of the game (below 3 per cent of GDP). No less importantly, some EMU members reported budget surpluses (including currently crisis-ridden Spain and Ireland). Similarly, other important global players, such as the United States and Japan, had manageable (less than 3 per cent) budget deficits, while Russia had a large budget surplus.

Table 1.4 Budget defi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I: The Economic Crisis in the European Union

- Part II: The EU’s Global Role and International Institutions

- Part III: The Crisis in Central and Eastern Europe

- Conclusion

- Index