- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

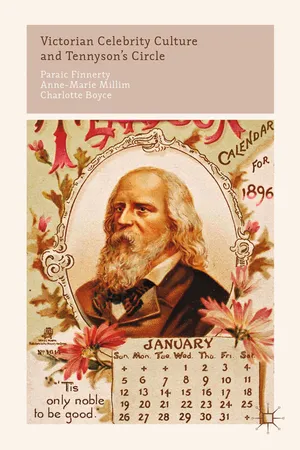

Victorian Celebrity Culture and Tennyson's Circle

About this book

Tennyson experienced at first hand the all-pervasive nature of celebrity culture. It caused him to retreat from the eyes of the world. This book delineates Tennyson's reluctant celebrity and its effects on his writings, on his coterie of famous and notable friends and on the ever-expanding, media-led circle of Tennyson's admirers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Victorian Celebrity Culture and Tennyson's Circle by C. Boyce,P. Finnerty,A. Millim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

At Home with Tennyson: Virtual Literary Tourism and the Commodification of Celebrity in the Periodical Press

Charlotte Boyce

An 1860 article in the family periodical the Leisure Hour, describing a summer ramble around the homes and haunts of famous poets on England’s south coast, concluded by encouraging readers to journey to the secluded region of Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. ‘Alfred Tennyson has selected this spot for his place of rest, and has shown his fine taste in doing so’, the article’s author enthused, adding, ‘altogether, for sweep and variety of view … there is nothing at all equal to it in the Isle of Wight, albeit it is at present the most neglected corner; and, as such, I commend it to all tourists’.1

The Tennysons would, no doubt, have been horrified by this recommendation. They had moved to Farringford, a house on the outskirts of Freshwater village, in 1853, hoping to find there the peace and privacy that had recently proved elusive in London.2 Unlike their previous Twickenham home, Farringford was (for the time being, at least) located far beyond the reach of the railways; it was also screened from public view by a mass of dense foliage, causing one visitor to remark, ‘I do not remember ever to have found such seclusion as was here possible. It seemed as if every tree that grew had felt a kind of personal responsibility to keep the intruder out’.3 By the 1860s, however, the tranquillity so coveted by the family was imperilled by the Isle of Wight’s status as a fashionable tourist destination – a status bolstered in no small part by the presence of the Laureate himself. His residence on the island was advertised in guidebooks that venerated Farringford as ‘a holy shrine’ or ‘hallowed ground’, a mustsee attraction for literary pilgrims.4 In periodicals, too, prospective travellers were tantalised with the possibility of face-to-face encounters with the poet, with articles routinely confiding that the downs above Tennyson’s home were the location of his ‘favourite nightly walk’.5 By positioning Freshwater as, simultaneously, a celebrity haunt and an area of picturesque beauty, suitable for ‘any tired denizen of our overgrown cities’ who ‘wants to avoid high prices and a crowd’, these publications worked, ironically, to attract the very masses whose absence they avowedly celebrated.6

This chapter argues that such contradictions are characteristic of the mass of articles on Tennyson and his homes that appeared in the British and American press during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Positioning these texts as virtual imitations of the Victorian practice of literary tourism, this chapter explores their paradoxical status and aims. I suggest that, though vested with the promise of genuine insight into Tennyson’s domestic life and physical surroundings, these articles in fact constructed only a simulated form of intimacy that, nevertheless, rendered literal contact between the poet and his readers unnecessary. Despite their facilitative function, however, these articles had a commercial interest in withholding as much as they revealed about the Laureate, for by maintaining his aura of inscrutability, they were able to both stimulate and perpetuate their readers’ desire for knowledge.

Virtualising literary tourism

According to one Victorian biographer, Farringford, during the period of Tennyson’s residence, ‘became one of the most overrun spots in Europe’, with ‘people lurking about the shrubberies, staring in at [the poet’s] windows, and watching him as he walked out of his gates’.7 This statement is perhaps a little hyperbolic; it is difficult to gauge the actual number of Victorian travellers to Farringford but, given the lack of efficient transportation to Freshwater, it seems unlikely that the house truly challenged the pre-eminence of continental tourist hotspots.8 Nevertheless, the notion that Tennyson was constantly besieged by hordes of inquisitive holidaymakers gained a kind of validity from its regular reiteration in Victorian print culture. A series of stock anecdotes – souvenir-hunters stripping branches from the tree planted at Farringford by Garibaldi in 1864, tourists spying on the poet as he ate his breakfast – appeared frequently in the periodical press, as well as in the memoirs and reminiscences of authorised visitors and guests.9 Tennyson’s semi-paranoiac reaction to these intrusive ‘Cockneys’, as he and his wife Emily rather contemptuously called them, was also well documented; according to one report, the poet once took alarm at the approach of a flock of sheep while out walking, having mistaken it for an advancing group of tourists.10 Eventually, Tennyson’s frustration with the perceived frequency and audacity of assaults on his privacy at Freshwater, combined with concerns over Emily’s health, led him to commission the building of a new home at Blackdown, on the Sussex–Surrey border. Aldworth was completed in 1869 and, from then on, the Tennysons routinely spent the summer months there, only returning to Farringford late in the autumn. Their self-imposed exile from the Isle of Wight was, like their residence there, widely reported, and further contributed to the mythology of the poet as an isolated figure keen to detach himself from his own celebrity.11

Whereas uninvited Victorian visitors to Farringford attracted the ire of Tennyson, more recently, the activities of such ‘literary tourists’ have piqued the interest of scholars. As Nicola J. Watson, among others, has noted, the nineteenth century saw the practice of visiting places associated with specific books and authors develop into a culturally and commercially significant phenomenon. During the period,

readers were seized en masse by a newly powerful desire to visit the graves, the birthplaces, and the carefully preserved homes of dead poets and men and women of letters; to contemplate the sites that writers had previously visited and written in or about; and eventually to traverse whole imaginary literary territories, such as ‘Dickens’ London’ or ‘Hardy’s Wessex’.12

As well as iconic literary sites and landscapes, of particular interest to Victorian tourists were writers’ houses. Harald Hendrix argues that the trend for journeying to celebrated authors’ homes reached ‘phenomenal proportions in the nineteenth century’ as readers increasingly sought to ‘go beyond their intellectual exchanges with texts’ and make ‘some kind of material contact with the author of those texts’.13 Houses associated with writers such as Wordsworth and Byron became popular stopping-off points on Britain’s tourist trail and were invested with a range of idiosyncratic and collectively constituted meanings; loci of the personally significant experiences of individual literary tourists, they also functioned as repositories of broader cultural values. Alexis Easley suggests that Victorian literary tourism worked to bring ‘coherence and meaning to modern experience’ by constructing a sense of unified national identity and shared cultural heritage.14 The houses of revered writers, as expressive but semantically mutable media, could be readily integrated into such narratives of nation-building and creative tradition.

Much critical attention has gathered around touristic appropriations of nineteenth-century writers’ houses in recent years. The meanings attached to places such as Abbotsford (home to Sir Walter Scott) and Haworth Parsonage (home to the Brontës), in particular, have been widely analysed.15 To date, though, very little has been written on either Farringford or Aldworth as objects of Victorian literary tourism, an omission that initially appears surprising. That Victorian tourists sought out Tennyson’s houses is indisputable. Moreover, the Laureate’s cultural cachet would, one might presume, have rendered his homes eminently assimilable into the kinds of narratives outlined above (making them, by extension, a source of interest to modern-day scholars). A couple of factors set Tennyson apart from the nineteenth-century writers whose houses have tended to receive the most touristic and critical notice, however. Unlike the majority of his literary contemporaries, Tennyson lived until the 1890s and this longevity meant that his residences were not available for adoption as focal points of nostalgic commemoration – architectural monuments to lost literary greatness – for the majority of the Victorian period. Nor have they been constructed as so since; following his death, Tennyson’s residences have remained in the hands of either family members or private owners and, in this way, have resisted the process of ‘musealisation’ (to adopt Polly Atkin’s useful term) to which other writers’ houses, bought and maintained by literary societies, fellowships and heritage bodies, have been subject.16

Yet, if Farringford and Aldworth can tell us little about the ‘culture industry’ of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the commercialisation of literary heritage and the practices of appropriation and memorialisation undertaken by modern-day literary tourists, their representation in Victorian print culture can give us valuable insights into literary tourism as a manifestation of Victorian celebrity culture, a relationship that has not always been fully recognised in critical studies to date. The tendency to concentrate on readerly interactions with the homes of dead authors in works such as Watson’s and, to a lesser extent, Easley’s implicitly positions literary tourism as a practice of posthumous commemoration, obscuring the important ways in which writers’ houses became enmeshed in nineteenth-century readers’ efforts to achieve quasi-personal relationships with their living literary idols. In fact, it was the public’s burgeoning fascination with inhabited writers’ houses that particularly concerned Victorian commentators. Erin Hazard notes that when literary tourism’s urtext, William Howitt’s Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent British Poets, was published in 1847, the British press expressed ‘fundamental misgivings about [Howitt’s] lack of differentiation between living and dead authors and about intrusion on living authors’ privacy’.17 The Examiner’s review was typical: ‘They [Howitt’s two volumes] contain too many modern and even living poets …What we acknowledge to be genuine emotion in the case of Spenser and Dryden, we may suspect to be prying curiosity in those of Wordsworth and Tennyson’.18

The reading public appears not to have been troubled by such scruples. By 1863, Homes and Haunts had reached its fifth edition and its success had spawned a number of imitative titles in both Britain and America.19 Its hybridised brand of literary biography, personal reminiscence and travelogue was also beginning to shape the tone and content of celebrity reportage in the periodical press.20 Departing from the societal focus of traditional gossip colum...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 At Home with Tennyson: Virtual Literary Tourism and the Commodification of Celebrity in the Periodical Press

- 2 ‘This Is the Sort of Fame for Which I Have Given My Life’: G. F. Watts, Edward Lear and Portraits of Fame and Nonsense

- 3 ‘She Shall Be Made Immortal’: Julia Margaret Cameron’s Photography and the Construction of Celebrity

- 4 Personal Museums: the Fan Diaries of Charles Dodgson and William Allingham

- 5 ‘Troops of Unrecording Friends’: Vicarious Celebrity in the Memoir

- 6 ‘Much Honour and Much Fame Were Lost’: Idylls of the King and Camelot’s Celebrity Circle

- Bibliography

- Index