eBook - ePub

Private Television in Western Europe

Content, Markets, Policies

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Private Television in Western Europe

Content, Markets, Policies

About this book

Private Television in Western Europe: Content, Markets, Policies describes, analyses and evaluates the phenomenon of private television in Europe, clustered around the themes of European and national experiences, content and markets, and policies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Private Television in Western Europe by K. Donders, C. Pauwels, J. Loisen, K. Donders,C. Pauwels,J. Loisen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Long Live Television

Christian Van Thillo1

Introduction

Pivotal moments like the 20-year anniversary of private television present the ideal opportunity to consider the past and look ahead to the future. However, before elaborating on private television’s past and future, it is worth looking at its current state of play.

Since the emergence of the Internet, television decline was predicted with clockwork-like regularity. The web would swiftly and eagerly take over its role as the leading medium. A new king was born.

Today, it is fair to say that these predictions have turned out to be false. The Internet is undoubtedly a new and attractive medium, but television still reigns in terms of its success with media consumers and advertisers.

Indeed, people watch more television than ever: viewing time for linear television has increased for the tenth year in a row in Europe, reaching an average of 222 minutes of viewing per person per day.

This shows that, in spite of all the hyped stories about the active lean-forward consumer, many people do not want to actively search for media products. On the contrary, most people still very much rely on someone else to do it for them. Choice is cherished but choosing is a chore.2 It is my belief that people like to be entertained, to be informed, to be guided, and television has proven to be a trustworthy guide. Building a television schedule is a carefully balanced exercise and it takes experience and knowhow to select, produce and promote high-quality content that is able to find the greatest common denominator in the varying tastes of viewers. Audience figures show that television succeeds in this difficult task. Moreover, faced with an abundance of choice, people will return to the brands they trust. In this respect it is remarkable that, despite the explosion of audiovisual content, the most successful television channels in Flanders today are the same ones as ten years ago.

Finally, even more surprising, at least for most self-declared visionaries, is the unremitting lure of television to advertisers. In recent years, with the Internet being able to target the media consumer with new advertising techniques, television advertising has been stigmatised as the “last bastion of unaccountable spending”.3 Today, however, the narrative power of television and its potential to reach out to mass audiences in a short period of time is, on the contrary, highly praised by advertisers.4

The continuous investments in television advertising are great news for viewers as they will benefit from more choice, better quality and increased services in a changing media environment.

The past: Development of commercial television in three phases

Since its emergence in the 1980s in most Member States of the European Union (EU), the private television market has developed and changed significantly.

Changes in the commercial television and related markets can be observed when we look at the following elements:

- barriers to entry into the commercial television market;

- the bargaining power of commercial television operators vis-à-vis other players in the market;

- product substitutes offered by commercial television operators; and

- the level of competition.

Generalising and simplifying to some extent, three phases can be discerned in the development of commercial television in Flanders and, although not entirely, by extension, Europe:

- 1980s to early 1990s: monopolistic commercial markets;

- mid-1990s to early twenty-first century: duopolistic commercial markets; and

- 2010–present: competitive rivalry across media markets.

1980s to early 1990s: Monopolistic commercial markets

In the early days of commercial television competition remained rather limited.

In the 1980s, even when monopolies on public broadcasting were abolished, high legal barriers to entry still existed in quite a few European countries. Through different means, governments attempted to protect commercial television players from immediate and fierce competition. A monopoly on advertising, entrusted to the Flemish Television Society (Vlaamse Televisie Maatschappij – VTM), existed to this end in Flanders. Other countries, giving more leeway to commercial television, were still strict in licensing commercial television channels, and in so doing limited competition in the domestic television market to a considerable extent.

Moreover, the number of commercial competitors remained low as the scarcity of analogue distribution still prevailed and public broadcasters were experiencing turmoil, seeing sharp decreases in audience reach in most Western European countries.

Within this context, commercial television was in a competitively advantageous position – certainly in densely cabled Flanders, with a near-100% audience reach for commercial television. Moreover, advertiser interest was high and the bargaining power of commercial television nearly absolute given the limited availability of other mass outlets and the vast popularity of commercial television with audiences. Also, with regard to content provision, commercial broadcasters were in a comfortable position, as supply was dispersed, whereas demand was concentrated within a limited number of commercial television players and public broadcasters with large in-house production units as well. Commercial television seemed to rule the television market, albeit – and this aspect should not too easily be set aside – that distributors enjoyed an even more attractive monopoly position.

Essentially, these were the early heydays of commercial television. Competitive rivalry was, in essence, limited, revenues from advertising increasing and stable, and audiences loyal.

Mid-1990s to early twenty-first century: Duopolistic commercial markets

The market changed gradually in the 1990s. Regulatory barriers were broken down by the European Courts, aiming to establish genuine market integration in broadcasting. Among others the advertising monopoly for VTM was abolished, which ended an exceptionally advantageous position for the only Flemish commercial broadcaster at that time. In essence, the European Courts convicted most measures aiming to protect domestic commercial players against competition.

Still, the scarcity through analogue distribution remained and, hence, provided a temporary technical protection against competition becoming too fierce. High financial barriers to entry into the commercial television market remained and only a couple of established players dominated most Member States’ markets for commercial television.

The Internet hype at that time had an impact on the position of commercial television players within the value chain. The Internet started to attract advertising budgets. Content providers became more powerful as well: more players in the market competed for highly attractive content. This resulted in higher costs for commercial television companies and the same for profits for content providers, which reaped the benefits of competition and introduced exclusivity and volume deals, bundling the acquisition of rights to several programmes in one deal.

Needless to say that competition for content, audiences (parts of which were migrating to the Internet already, experimenting with gaming, etc.) and revenues was more fierce in this period than in commercial television’s early days. Competition was, moreover, not only limited to commercial television operators, but also became fierce between the leading commercial television operator(s) on the one hand and the public broadcaster on the other. Indeed, the latter engaged in more commercial programming strategies. These resulted in increasing audience shares for public broadcasters, but induced criticism on the convergence between programming schemes of commercial and public broadcasters and, hence, distortion of competition as well.

2010–present: Competitive rivalry across media markets

Whereas commercial television was still more or less in a comfortable duopolistic market in the 1990s and the first years of the twenty-first century, the convergence between technologies and digitisation has changed the market of commercial television in unprecedented ways. New competitors, notably from telecommunications and ICT markets, are entering a market that was previously rather closed to competition from outside the core market (be it for economic, technical or regulatory reasons). Digital distribution capacity increased significantly.

The competitive rivalry that has emerged since 2010 is challenging traditional commercial television in various ways. First, the new competitors we are faced with are often wealthier and in control of platforms. The sales of football rights to telecommunications operators like Belgacom or cable operator Telenet in Flanders is just one example. The recent news alerts that both Apple and Google plan to make a bid for the rights to the broadcasting rights of the English Premier League are another. Second, and related to the former, one cannot deny that these new players are hardly bound by regulation. Whereas commercial free-to-air players operate their television channels, respecting tight regulatory schemes (e.g. on advertising, European content, independent production), the new entrants in the market face virtually no rules under the pretext of innovation.

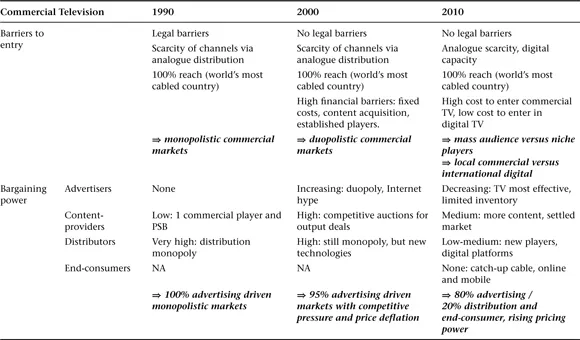

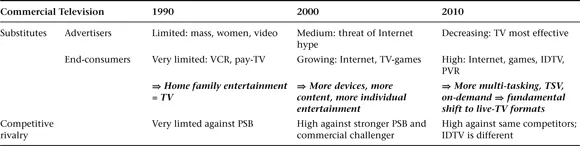

Summing up, the market for commercial television went from monopoly, over duopoly to competition (see Table 1.1).

The future

At a time when convergence is becoming reality, with connected televisions that combine the Internet and television in one device, competition will only get fiercer.

In itself competition is beneficial because it is a great opportunity to combine the best of both worlds. But we need a real level playing field to realise this: all companies in the market need to play the game of competition with equal means and need to respect each others’ business models.

Table 1.1 The development of commercial television in three phases

Source: Author; based on Porter, 1985

Indeed, while television as a medium is in excellent shape, the danger comes from technology companies that invest in fancy platforms, but at the same time ignore the investment in television content. By delivering content they do not pay for, or selling content far below the price of its creation, these distributors become “parasites” on the media companies that invest substantially in journalists, programmes and actors.5 This dynamic destroys the economic incentive to create the kinds of movies, television and journalism that consumers demand, and for which they are, in fact, quite willing to pay.

It is the responsibility of broadcasters to find smart partnerships with the increasingly complex web of distributors. But policy needs to facilitate the level playing field by all means since a distribution platform with little to distribute is of little use to consumers no matter how fancy the interface is.6

And this is not a conspiracy of an old medium to stop technology or thwart user choice here; it is a rational business strategy, pure and simple.7

There lies the real challenge for the future of television. A challenge that cannot be tackled by television itself but one that needs to be addressed v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword by Philippe Delusinne

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Long Live Television

- Part I: European and National Experiences

- Part II: Content (and) Markets

- Part III: Policies

- Index