- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

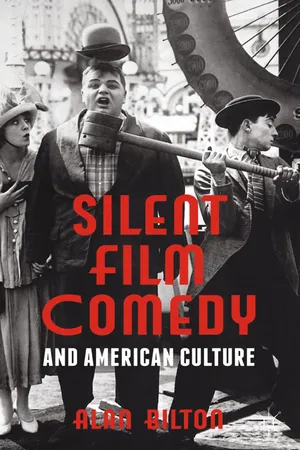

Silent Film Comedy and American Culture

About this book

This absorbing study of early 20th Century American Culture interprets the anarchic absurdity of slapstick movies as a form of collective anxiety dream, their fantastical images and illogical gags expressing the unconscious wishes and fears of the modern age, in a way that foreshadows the concerns of our own celebrity-obsessed consumer culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Silent Film Comedy and American Culture by Alan Bilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introducing American Silent Film Comedy: Clowns, Conformity, Consumerism

The US’s great spree of the 1920s, seen by many at the time as a cultural surrender to indulgence and excess, was overseen by a succession of rather dull, earnest, Republican presidents, of whom by far the most sober and earnest was Calvin Coolidge, the erstwhile ‘Silent Cal’, noted for his dour, prudent, almost obsessively sensible and parsimonious personality. Worried that the public’s perception of him as a humourless bookkeeper was damaging to the party, Coolidge’s advisors hired Edward Bernays, show-business impresario, godfather of the new black art of Public Relations and Sigmund Freud’s nephew, to add lustre to his presidential image. Bernays’s first response was to photograph Coolidge posing alongside several of his movie-star clients; but, if anything, this stunt only succeeded in making the president appear even more stiff and awkward. Undeterred, Bernays dressed Coolidge first in full cowboy gear, then in Indian headdress, before finally shooting him milking cows on his family farm, none of which succeeded in linking Coolidge’s air of propriety to the US’s mythic past. Finally, however, Bernays’s agency hit upon a plan: they installed in the White House a mechanical horse, which was electrically operated and capable of high speeds, and they filmed Coolidge proudly mounted atop it, dressed in a Stetson hat and (apparently) whooping and hollering. When Bernays placed the story in the press, reporting that the president rode his steed up to three times a day, Coolidge was widely ridiculed. But, as ever, the temperate, sedate Cal took it all in good part: ‘Well, it’s good for people to laugh’, he dryly noted (Evans, 1998, p. 203).

The image of the straight-laced and hide-bound Silent Cal spinning and cheering atop his mechanical colt has entered history, and acts as a kind of guiding image for this book, both a study of silent film and an exploration of the shift from Puritan restraint to materialist excess in the early years of the twentieth century. While Coolidge himself was almost pathologically prudent and parsimonious in his dealings, his pro-business policies nonetheless ushered in a new era of luxury and excess; it is this mass cultural St Vitas dance (St Vitas also being the patron saint of travelling entertainers) which provides the context to this study.

In 1925, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, who would, of course, go on to become Coolidge’s successor in the White House, spoke to the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World in Houston, stating ‘You have taken on the job of creating desire. You have still another job – creating good will in order to make desire stand hitched. In economics the torments of desire in turn create demand, and from demand we create production, and thence around the cycle we land with increased standards of living’.1 This idea of ‘hitching’ desire to the marketplace, deploying its ‘torments’ as a kind of internal combustion engine, man driven like a wound-up toy or spinning top, appears again and again in the business rhetoric of the decade. The market is referred to as a kind of perpetual motion device, transporting goods from factory to worker in one continuous loop. It also spills over into the film culture of the decade: the manic choreography of racing torsos in Mack Sennet’s Keystone movies; the staccato judder of Charlie Chaplin’s tramp; Buster Keaton’s revolving house in One Week (1920), a mass cultural dream of speed, machinery and consumption. And it is indeed cinema, and its relation to the new consumer culture, which provides the subtext to Hoover’s speech.

The engineers of desire

At this point we return to the work of Edward Bernays, by now one of Hoover’s key speech-writers, as well as being one of the most important (if least known) architects of Western consumer culture. Bernays’s links to his Uncle Sigmund are central here: Bernays’s family had moved to the US when he was only one, but Bernays remained close to his famous uncle throughout his life, and was, perhaps, the first thinker to fully grasp the economic as well as the philosophical implications of psychoanalysis. Bernays started off as a Broadway press agent (his first success was the promotion of a dubiously educational play about the dangers of venereal disease entitled Damaged Goods (1901)) before acting as head of publicity for turns as famous as the Great Caruso (singer Enrico Caruso, 1873–1921) and Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes (1909–1929). In 1917, he joined George Creel’s Committee on Public Information, the government-sponsored propaganda organization which was instrumental in the selling of the US’s actions in the First World War. Afterwards, Bernays returned to the fame game, concentrating on movie-star clients, including Clara Bow, as well as establishing the new field of ‘public relations’, a science that he regarded as rooted in the discoveries of his Uncle Siggy, whose works he also promoted in the US.

What linked all these disparate business enterprises was Bernays’s crucial idea that the mass media might be used as a tool to pacify and control the irrational and voracious unconscious of the great American public, a public which in Bernays’s writing appears as a barbaric, destructive crowd. Like many influential intellectuals of the period (including Walter Lippmann, Harold Mencken and, of course, Freud himself) Bernays was suspicious of the very concept of democracy. Man could not be expected to make rational political decisions, he believed, because man was not governed by rational, lucid or reasonable impulses. Rather, civilization was merely the fragile (and temporary) subjugation of primeval sexual and aggressive forces, primitive reminders of our animal past that could erupt at any point. The mass slaughter of the trenches, the rise of anti-Semitic fascism, the angry Bolshevik mob: all these seemed to Bernays to vindicate his position, the carnal house of history mocking the rational, technocratic utopia which seemed briefly tenable at the dawn of the twentieth century. But unlike his pessimistic European uncle, the American millionaire Bernays had a solution: if these unconscious desires could be linked to the marketplace, urges both stimulated and satiated by images, products and luxury goods, then mass culture itself could be used as a tool to domesticate and pacify the energies of the unconscious. The masses had to be scientifically managed, public opinion strictly controlled; Bernays called this ‘the engineering of consent’.2 The key to this was not reason, but the irrational forces psychoanalysis had dragged into the light.

After all, his uncle’s theories also provided a theoretical justification for Bernays’s distrust of the masses and their pack mentality. In his 1921 essay ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego’, Freud argued that the mob was connected with ‘all that is evil in the human mind’, advancing the notion that, when safely hidden with the massed ranks, man succumbed to an aggressive ‘desublimation’, shedding any last vestments of civilized behaviour (Freud, 2004, p. 25). The crowd, Freud wrote, resembled the destructive energies of the id, throwing off the chains of repression in accordance with the most primitive of urges. Acting like vengeful children, eager to exact retribution on a civilization that demanded such a severe renunciation of their drives, the crowd infantilized its members: akin to school children cooped up on a wet day, these dangerous anarchic energies would, he believed, ultimately find expression only via mindless acts of destruction. Elias Canetti, writing in 1931, wrote that the horde ‘hungers to seize and engulf everything within reach. It wants to experience for itself the strongest possible feeling of its animal force and passion. It is naturally destructive, enjoying the demolition of homes and objects apparently as an end in itself’ (Carey, 1992, p. 30). Moreover, a second, and perhaps even more dangerous phenomenon, would then assert itself: having regressed to the status of children, these demonic infants would then seek out a father figure, a strong leader or ‘Caesar’ to lead them. Having already abdicated all responsibility for their actions by succumbing to the mindless drives of the id, their next step would be to dissolve the discriminating ego forever, seeking absorption within the adoring crowds gathered at the feet of der fuehrer or Uncle Joe. In the light of this veneration of the father, democracy seemed too weak a dam to hold back such terrifying psychic forces; what was needed, according to Bernays, was a new technocratic elite, ‘a highly educated class of opinion-moulding tacticians constantly at work, analysing the social terrain and adjusting the mental scenery from which the public mind, with its limited intellect, derives its opinions’ (Ewen, 1996, p. 10). And what was this ‘mental scenery’ composed of? Movies, adverts, catalogues, billboards: the ‘hieroglyphic civilization’ (the phrase is Vachel Lindsay’s) of American consumerism.

Hired by a tobacco company to promote the idea of women smoking, Bernays orchestrated a highly original press campaign that played upon the idea of the cigarette as a symbol of phallic power. At a suffragette protest in 1919, Bernays hired a number of pretty women to be photographed suggestively removing a packet of cigarettes from beneath their garter belts and lighting up in public. The sexual charge of this image (as well as the linking of cigarettes with male freedom) excited the public imagination and increased sales overnight. Imagery could also be deployed which drew upon sexual anxiety and discomfort. For example, Bernays was paid by Dixie Cups to promote the sales of disposable plastic cups, and he did so by linking the imagery of an over-flowing cup with subliminal images of vaginas and sexual disease – obviously those months spent promoting Damaged Goods had not been in vain. Suddenly, Freud’s exegesis of dream symbolism seemed like the answer to every salesman’s dream, a way to bypass rational reservations and access primitive wants and fears directly. However, Bernays was interested in more than simply making money: he was concerned with the preservation of capitalism itself.

After the First World War, the unprecedented economic boom suddenly created fears of mass over-production. The US was now producing vastly more goods than its domestic market could handle, or that warravaged Europe could afford. The answer was to convince American consumers to buy more, to shift consumption from what one needed to what one desired. Bernays argued that people had to be trained to desire, to want new things before the old things had even started to wear out. This, in turn, required a complete transformation of the American attitude towards money: Americans had to think of buying not as an extravagance but as their patriotic duty. Hoarding money as ‘savings’ was seen as a throwback to a repressive Puritanism (anally retentive in Freud’s view): modern US required its dollars as rocket fuel (Susman, 1984, p. 111). Increasingly, this was a society that defined itself in terms of abundance rather than scarcity; the pioneer struggle to subdue a wild continent was replaced by indulgence, leisure and pleasure. Who still needed to stoically ‘make-do’, to scrimp and save, or neglect one’s own personal happiness in the communal project of building a new civilization? Hard work and self-denial belonged to the past: now it was the turn of personal desire and self-gratification, qualities which needed to be stimulated in order that the economy which permitted such laxity and ease could continue to grow.

To increase expenditure and demand, advertisers made consumerism an expression of one’s self. They promoted buying one’s personality off the peg, as it were, or defining oneself not through one’s family, hometown, religion or job, but rather through one’s clothes, home, car or lifestyle. Whereas goods were once marketed in terms of their use or durability, advertisers in the 1920s increasingly linked their products to the idealized lifestyles of the young, beautiful and rich: what counted was not the product per se, but the lifestyle or emotional connotations attached to it. This, then, was the great discovery of the age: that we buy not what we need, but rather what contributes to a fantasy version of who we long to be. Both the movie screen and the department store window offered distorted reflections of who one might become – a new identity, a new beginning, a new you – a notion, of course, rooted in the mythic promises of the US itself.

But Bernays was thinking even larger than that. While Europe seemed to be drifting towards either fascism or communism, either stripe defined by brutal, anti-bourgeois mobs, the American dream seemed to offer an alternative, a union of entertainment and consumerism, film and advertising. ‘The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in a democratic society’, wrote Bernays in Propaganda in 1928, in a chapter headed, significantly, ‘Organizing Chaos’. ‘Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country’ (Bernays, 1928, p. 9). And who made up this invisible government? Advertisers, marketing strategists and, crucially, film-makers. Scientific studies carried out on children in the early 1920s suggested that ‘motion pictures affect sleep, their vital processes, their supply of information and misinformation, their attitudes and their conduct’ (Doob, 1935, p. 376). Could film, then, make compliant children of us all? After all, cinema also manufactured an emphatic state of Mitspielen, or nervous excitement, ‘polarizing’ the mental field: ‘It is almost impossible for him [the viewer] to avoid the picture’, Bernays wrote: ‘the darkened room, with the screen as the only point of illumination, compels him to be orientated toward that screen’ (Doob, 1935, p. 374). In the movie theatre, Georges Duhamel noted, ‘I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images’ (Benjamin, 1992, p. 231). But what kind of images were these? Motion pictures, like other branches of advertising, appeared to Bernays as a kind of collective visualization of desire. ‘When the herd must think for itself’, he noted contemptuously, ‘it does so by means of clichés, pat words or images which stand for a whole group of ideas or expressions’ (Bernays, 1928, p. 51). Thus, just as the mechanics of projection reorganized perception, so the flow of images could also reorganize the object of desire.

As Leonard Doob noted in his 1935 work, Propaganda: Its Psychology and Technique,

Similarly as the sailor on a lonely waste of sea seeks his consolation in brandy and the soldier during the war his in nicotine, in like manner does the worker from the factory, the department store, and the office so often find refuge in the movies after forsaking his treadmill, because in general movies offer him precisely what he is seeking: fantasy and sensation, in contrast to his own monotonous life, and illusory transplantation into a land of wishes containing luxury and riches, the erotic and the exotic … .

(Doob, 1935, p. 374)

When asked about the Soviet threat, pro-business booster Bruce Barton could answer confidently: ‘Give every Russian a copy of the latest Sears-Roebuck Catalogue and the address of the nearest Sears-Roebuck outlet’; Henry Ford went even further, situating consumerism and mechanization at the heart of what seemed an airtight system, a closed loop wherein the worker toils ceaselessly on the conveyor belt in order to purchase the very goods that come off it (Susman, 1984, p. 128). For Ford, this social control seemed the antithesis of the anarchy breaking out elsewhere in the world (he famously could not bear surprises, and demanded that publishers send him copies of Little Orphan Annie in advance so that he could read his paper unperturbed), the American way propounded in after-work classes set up by his ‘Sociological Department’. Bernays also believed that the fundamental mechanics of escapism and desire could be used to tranquillize the masses, keeping them docile and happy. Sexual or aggressive impulses could be sublimated via idealized images and thereby managed and controlled, turned into advertising images, motion-picture scripts, collective dreams. Walter Lippmann in his seminal 1922 work On Public Opinion argued that it was the task of ‘image-makers’ to reconcile consumers to this new social reality, that narcissism could act as an instrument of profound social control. Like Bernays, he believed that as long as new products were constantly created to both stimulate and satisfy desire, this model could be used as the basis of both economic and social stability. After all, if our very sense of who we are – or rather who we most want to be – is dependent upon our buying the ticket, purchasing the product or internalizing the image, then consumption becomes the very keystone of our existence: I Shop Therefore I Am. ‘Men are rarely aware of the real reasons which motivate their actions’, wrote Freud’s nephew. ‘A man may believe that he buys a motor-car because, after careful study of the technical features of all makes on the market, he has concluded that this is best. He is almost certainly fooling himself’ (Bernays, 1928, p. 51). No, Bernays argues, in reality cars are sold because of fantasies of freedom, sexuality, wealth, ‘evidence of his success in business, or a means of pleasing his wife’ (Bernays, 1928, p. 52). The persona we present to the world ultimately becomes our own mode of recognizing who we are; the ad maketh the star, then maketh the man.

Bernays was one of the first entrepreneurs to understand the importance of product placement in films (the mere appearance of a brand of perfume in a DeMille flick was worth millions of dollars) and to employ the idea of celebrity endorsement: his company sold Clara Bow eye-drops, for example. But far more important was his idea of mobilizing the essential mechanics of anxiety and desire through mediated images, images which, he believed, accessed the unconscious in a far more direct way than language. Psychologists taught of the existence of ‘hard-wired responses in human beings that function as a result of the visual cues to which they are exposed’ (Berger, 2004, p. 10). Fears, wants, irrational impulses, the rejection of reality and regression into infantile fantasy: all these could be managed, almost invisibly, by the entertainment industry. Sexual and violent drives, inimical to civilization, could be redirected to socially and economically productive ends; all the public had to do was to learn to dream other people’s dreams.

Perception management and the American way

Lippmann argued that, in the wake of the First World War, there was now a great need to re-order social images in order to fit the new reality of a new world; this, in turn, necessitated the manipulation of how people saw things, a transformation of vision itself. Cinema certainly provided a shop window for mass-produced goods. But perhaps it could do much more, working to stabilize a culture’s collective unconscious, creating a kind of rest cure for the collective shell-shock of both modernization and the First World War – not for nothing was the Roxy in New York known as ‘The Cathedral of the Motion Picture’ or the theatre on 55th Street nicknamed ‘The Sanctuary’. Progressive reformer Paul W. Goldberg praised slapstick comedy as a salve for the ‘mental stress and emotional fatigue’ of twentieth-century life with its ‘dull grey colours, straight lines and sharp angles’ (Jenkins, 1992, p. 45). Could film help tame and domesticate the common throng, transforming the crowd into a passive, paying audience? Images of an angry crowd or mob – am...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- A Brief Chronology of Silent Film Comedy

- 1. Introducing American Silent Film Comedy: Clowns, Conformity, Consumerism

- 2. A Convention of Crazy Bugs: Mack Sennett and the US’s Immigrant Unconscious

- 3. Accelerated Bodies and Jumping Jacks: Automata, Mannequins and Toys in the Films of Charlie Chaplin

- 4. Nobody Loves a Fat Man: Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle and Conspicuous Consumption in the US of the 1920s

- 5. Dizzy Doras and Big-Eyed Beauties: Mabel Normand and the Notion of the Female Clown

- 6. Consumerism and Its Discontents: Harold Lloyd and the Anxieties of Capitalism

- 7. Buster Keaton and the American South: The First Things and the Last

- 8. The Shell-Shocked Silents: Langdon, Repetition-Compulsion and the First World War

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index