eBook - ePub

The Ministry of Public Input

Integrating Citizen Views into Political Leadership

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As political leaders acknowledge the limits of their power they increasingly integrate constructive input from inside and outside government into their decision-making. A Ministry or Commission of Public Input is necessary to collect, process and communicate input more effectively and politicians need to work with the public to identify solutions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ministry of Public Input by J. Lees-Marshment in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Gouvernement américain. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Building the Bridge: A Methodology for Connecting the Aspiration and Practicalities of Public Input and Political Leadership

Political leadership is undergoing a profound evolution that changes the role that politicians – and the public – play in decision-making in democracy. Rather than simply wait for voters to exercise their judgement in elections, political elites now use an increasingly varied range of public input mechanisms, including consultation, deliberation, informal meetings, travels out in the field, visits to the frontline and market research to obtain feedback before and after they are elected. Whilst politicians have always solicited public opinion in one form or another, the nature, scale and purpose of mechanisms that seek citizen involvement in policymaking are becoming more diversified and extensive. Government ministers collect public input at all levels of government, across departments, and through politician’s own offices, in many different ways and at all stages of the policy process. Such input is at present uncoordinated, dispersed and often even unseen, but if added together would represent a vast amount of money and resources spent seeking views from outside government. Furthermore, world leaders and senior politicians are increasingly talking of working in partnership with the public, initiating highly visible public input exercises and conceding they themselves do not have all the answers. President Barack Obama has noted that ‘government does not have all the answers,’ that there is a need to find new ways of ‘tapping the knowledge and experience of ordinary Americans’ and that ‘the way to solve the problems of the time is by involving the American people in shaping the policies that affect their lives’;1 Prime Minister Julia Gillard said that the government was ‘eager to tap into’ the insights and perspectives of the public;2 Prime Minister David Cameron stated that ‘the old politician knows [even the] best system … just doesn’t work’ and that government and the people ‘need to work together to make life better’;3 and Prime Minister John Key conceded: ‘we know we don’t have all the answers,’ and the public and the government need to ‘work together.’4 Alongside this, more innovative public input mechanisms are being adopted that seek more than immediate, static and consumerist demands by utilising more deliberative and creative methods to encourage citizens to offer more constructive suggestions for problem-solving.

The expansion and diversification of public input has the potential to inform and influence our leaders’ decisions, strengthening citizen voices within the political system and thereby improving policy outcomes and enhancing democracy. However, continual public input into government raises profound practical and democratic questions, including:

•How can the public offer useful input? Given they are not aware of the challenges and constraints of government that political leaders have to take account of when in power.

•How do we ensure that public input is collected and processed appropriately within the government? Given the current practice is hindered by ineffective organisation, resourcing, timing and connection to policy processes.

•What are political leaders supposed to do with that public input? Given that elected leaders have to make the final decision and need to exercise political leadership to achieve change and societal progress.

There is a big gap between research on, and the practice of, public input and political leadership in government. No one has identified how political leaders can use public input once they receive it within the context of the highly challenging political environment that politicians face once they are in government, or how they should integrate this input into leadership, which requires pursuing change and necessary but not always popular policies. There is of course already an extensive and valuable literature on public input in government in several academic fields, such as: public administration, which discusses consultation; political theory, which offers the concept of deliberative democracy and where it is argued that carefully constructed public discussion on issues should lead to decisions on policy; political marketing, which explores market research; and political leadership, which critiques politicians’ use of opinion polls. However there is little holistic work that cuts across all of them and provides answers for how to integrate public input into political leadership. Separation between different academic fields and practitioners and politicians creates silos which has prevented consideration of the holistic impact that all types of public input have on political leadership.

Additional gaps include that the vast majority of literature on consultation or deliberation focuses on that run by local councils or non-governmental organisations rather than on presidential or prime-ministerial-level politics (Flinders and Curry 2008, 372; Young in Fung 2004, 51; Hartz-Karp and Briand 2009, 134), on the political realities of federal and central government and on the perspective of politicians. A rare study which interviewed state-level elected politicians reported that ‘legislators doubt the viability of public deliberation – especially its political feasibility’ (Nabatchi and Farrar 2011a) and, as Lee (2011, 13) noted, one false assumption in the deliberative democracy literature is that the expansion of public deliberation processes is the result of a grassroots deliberation movement when, in fact, ‘so much of the activity in the field is driven by elite actors’. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is a lack of research on the perspective of politicians at central-government level, with studies favouring interviews with government staff instead of politicians (e.g., Offenbacker and Springer 2008; Frederickson 1999; Ray et al. 2008) or exploring ministerial effectiveness other than how to deal with public input and show leadership (e.g., Riddell et al. 2011). Thus it is important to consider the perspective of the political elite. Academia has not yet connected its knowledge and understanding of both the ideals and realities of government and leadership with public input, which prevents it from identifying solutions to make the process of public input an effective part of modern governance. Despite the wealth of literature on deliberative democracy and the common lament that politicians do not use or take up deliberative events, few scholars or practitioners have stopped to consider why or what to do about this. The state or government part of the process has been neglected in academic – and practitioner – discussion: Abers and Keck (2009, 292) note how ‘scholars emphasize either the input side of policy (deliberation, participation) or on the output side (accountability). Neglected in this story is the throughput.’

The final gap to bridge is the lack of solutions. UK practitioner Edward Andersson from Involve conceded when interviewed that ‘[I]t is often easier to find bad examples rather than easier examples. The bad examples come up and hit you in the face while the good examples are much more subtle’ (Andersson 2010). Furthermore, academic research is traditionally designed to act as a source of objective criticism of elites and thus leans to providing more negative than positive accounts. As Goodin (2009b, 36) noted, there is ‘a long tradition in policy studies that delights in exposing failure.’ This has helped to identify the many weaknesses in public input practices – the problem – but there is little suggestion as to how to overcome this – the solution (see Karpowitz et al. 2009, 605; Gunningham 2009, 147; Carson 2010).

Whilst of course providing a critique of government practice is an important and vital part of university’s role in society, it is difficult to move practice forward without reasonable, doable proposals for improved action. Politicians and practitioners need research that provides recommendations for best practice rather than impractical theoretical ideas or ‘what-you-did-wrong’ lists from research into the past. This book thus seeks to bridge these gaps by identifying ways to integrate public input into government within the constraints of government in a way that allows politicians to exercise effective leadership. In doing so it takes into account both the theoretical and democratic ideals of public input and leadership and the practical realities of public skills and government. It also seeks to identify recommendations for government on how to run public-input practices better in future. There is wasted hope in current practice in government public input. Substantial public funds are spent in scattered and superficial activity which produces data that politicians can rarely use and disappoints those who run and are involved and thus, not surprisingly, has a limited or negative impact on decision-making and government–citizen relations. Improving public input in government would not require lots of new money – the money is already in the system. No one has totalled it up because the activity is so dispersed among different government departments and ministries, units within them, and across different types of staff and forms of public input. Half of the overall budget could be spent for double the impact if channelled into one unit that can collect and process input more effectively and to a higher standard for all areas of government. We need to do less but do it better, cutting costs and increasing quality. But at the moment so much of the collection and processing of public input is run badly, and only serves to create more distrust between politicians and the public. Inferior forms of public input make political leadership harder, and politicians appear to be ignoring the views of those they seek to represent. Public input into government is already happening, but happening badly; we need to find a way to make this work better within the realities of government and leadership and restore the hope raised by the theoretical ideals of public input.

Methodology

As Peele (2005) advocates, studies of political leadership need to be open to ‘an eclectic approach’ which allows ‘experimentation with different approaches, techniques and frameworks’ in order to ‘unlock the secrets of what is a multifaceted process.’ This research utilised several methods and approaches and drew on a wide range of sources. The process included theoretical and empirical research, utilised an appreciative inquiry approach, completed a synthesis of over 200 government, non-governmental and media documents, included an academic–practitioner workshop, considered public comments by prime ministers and presidents it conducted and analysed interviews with practitioners working in, for and outside government in the areas of consultation, market research, policy and strategy, and interviews with current or recent government ministers and secretaries. The research adopted a broad definition of public input:

Public input includes market research, policy research, meetings between members of the public and politicians both formal/organised and informal/spontaneous, public letters/emails/calls to politicians, formal consultation, including legislative hearings and deliberative events.

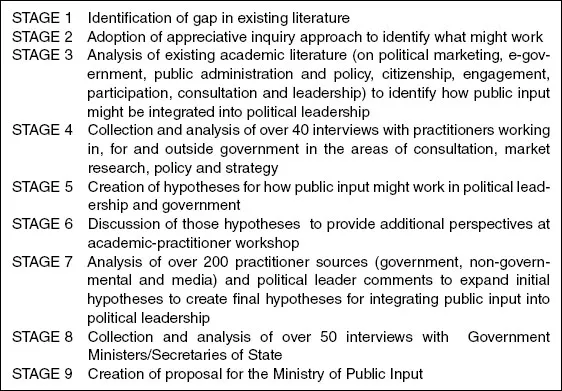

Any form of public input that conveys the views, experiences, behaviour and knowledge of those in society who are not elected figures (i.e., politicians) in government is relevant; therefore the public includes academic experts, policy experts, think tanks and stakeholder/interest groups as well as ordinary members of the public. Figure 1.1 summarises the different stages in the research.

Stage 1, identifying the gap in the literature, has already been discussed, but every subsequent stage of the research will be explained in detail.

Stage 2: Adoption of appreciative inquiry approach to identify what might work

In terms of overall approach, this research utilises an appreciative-inquiry (AI) approach. There is already a vast literature identifying weaknesses in the practice of collecting and using public input. Political marketing laments the over-use of focus groups; political leadership debates too much reliance on polls, and deliberative democracy the lack of elite response to deliberative events. Thus this research adopted an appreciative-inquiry approach to identify what might actually work. AI is used in practice by consultants to identify how things can work and thus foster positive change. It seeks to identify the best of existing behaviour –‘what is’– to support the development of the future – ‘what might be.’ AI asks what have we done well and what more can be done (Messerschmidt 2008, 455). The methodology emerged through the work of David Cooperrider in the 1980s when he asked medical doctors to talk about their biggest successes as well as their biggest failures; and during analysis he was drawn to the success stories and what worked to create such success. He thus proceeded to work on identifying what worked, and then he speculated on future ‘potentials and possibilities’ to create a theory of future possibility, with the previous success stories being used to vivify such potential (see Cooperrider et al. 2008, xxvii) and then stimulate organisational change.

Figure 1.1 Summary of methodology behind the Ministry of Public Input

Transformational inquiry, action research and imaginative theorising are part of the AI approach, as are creativity, vision, new knowledge, possibilities and innovation. Cooperrider et al. (2008, xii, xvi–xxvi) note how research on AI has been conducted in organisations around the world, promoting significant organisational change in a range of institutions, such as British Airways, the ANZ Bank, NASA, Save the Children and the UN. It has also been used in international development, including a range of successful programmes, such as Habitat for Humanity and UNICEF (Messerschmidt 2008, 455; Odell and Mohr 2007, 309–310). Odell and Mohr (2007, 312) argue that ‘if you look for problems, you find – and create – more problems,’ whereas ‘if you look for success, you find – and create – more successes.’ An Australian practitioner, Vivien Twyfords, suggested the research could adopt the academic methodology AI to enable it to take a more positive approach. AI is defined as a ‘co-operative co-evolutionary search’ (Cooperrider et al. 2008, 3); it is a collaborative method. This fits with the focus on how politics is receiving input from both politicians and the public, and they need to work together.

AI also seeks to be practical and ‘translate images of possibilities into reality and belief into practice’ (Cooperrider et al. 2008, xi). This fits the goal of this research to connect democratic theory such as deliberative democracy and practical politics such as political marketing. The need for this research to be realistic and practical was hammered into me when I was an invited participant at a workshop in 2010 on the deliberative democracy in Australasia, led by Lyn Carson and hosted by the Centre for Citizenship and Public Policy, University of Western Sydney. Most of the other practitioners and academics, with expertise deliberation and consultation, bemoaned the lack of relationship between deliberation and government but had not had the opportunity to consider the perspective of politicians and the electioneering and governing realities they have to face. There was clearly a need to merge understanding from a range of fields and to focus on solutions.

Appreciative inquiry suggests a four-step process (see Cooperrider and Srivastva 1987; Whitney and Cooperrider 2000): discovery: identifying what works well already; dream: imagining what might be and what is needed; design: how can this work; and destiny: how to engender this change. This book will go through the first three steps, exploring how to make public input into politics work by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Building the Bridge: A Methodology for Connecting the Aspirations and Practicalities of Public Input and Political Leadership

- 2 Changing Times: Politicians Talk of Partnership

- 3 Mind the Gap: The Ideals of Public Input and the Mucky Reality of Government

- 4 Collecting Public Input

- 5 Processing Public Input

- 6 Developing Political Leaders and the Public

- 7 Ministers on Managing Public Input

- 8 Ministers on Integrating Public Input into Decision-Making

- 9 Deliberative Political Leadership and the Ministry of Public Input

- Notes

- References

- Index