eBook - ePub

Aid as Handmaiden for the Development of Institutions

A New Comparative Perspective

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aid as Handmaiden for the Development of Institutions

A New Comparative Perspective

About this book

Through comparative studies of aid-supported infrastructure projects in East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, the book examines how aid could assist development processes by facilitating development of local endogenous institutions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Aid as Handmaiden for the Development of Institutions by M. Nissanke, Y. Shimomura, M. Nissanke,Y. Shimomura in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Institutional Evolution through Development Cooperation: An Overview

Machiko Nissanke and Yasutami Shimomura

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Background

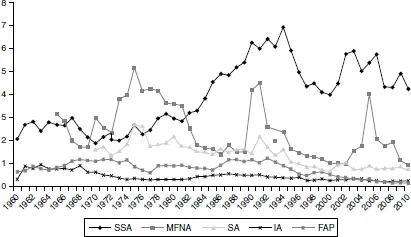

Despite a significant injection of foreign aid since gaining political independence, most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa entered the new millennium as heavily dependent on official aid for sustaining socio-economic development. This record should be assessed against the backdrop, whereby throughout the protracted debt crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, the traditional donor community dominated the economic policy debates of a large number of heavily indebted countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, and it tried to exercise a firm grip on the process of economic and governance reforms in Africa, leveraging reforms for more aid in one form or another at large. As shown in Figure 1.1, where official development assistance (ODA) received is shown as a percentage of Gross National Income (GNI) by regional groups, this situation was quite a sharp contrast to the experiences in the East Asia and Pacific region (EAP) in the post-war years, where most countries managed to reduce their reliance on foreign aid over time, with many graduating successfully from the aid-recipient status altogether.

However, over a matter of one decade or so since the dawn of the 21st century, the aid landscape has undergone quite remarkable changes. As O’Keefe (2007) notes, the diversity of aid providers today is leading to pluralism and fragmentation in aid provision with increasing competition among them.1 It is fair to state that the aid landscape has changed more dramatically in Sub-Saharan Africa than any other developing regions over the past decade. The commodity boom since 2002, triggered and sustained largely by a thirst for resources from emerging economies, in particular the ‘Asian Drivers’ such as China and India, has led the scramble for natural resources globally, and the resource-rich African continent is suddenly in the limelight with uplifted interests from global investors in search of investment and business opportunities hitherto unforeseen in the region. Thus, there appears to be a real sea-change in investors’ perceptions of Sub-Saharan Africa, for which countries in the region have longed over many decades, as they desperately require real investment, not ‘hand-outs’, from the rest of the world.

Figure 1.1 Overseas development aid received as percentage of GNI by regional groups of developing countries

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicator.

Along with other global players, many emerging economies such as Brazil, China, India, Turkey and South Korea as well as capital-rich Gulf states have rapidly expanded their economic relationships with African countries and increasingly engaged with Africa as a critical partner for economic development, proclaiming a new form of economic relationship through ‘South-South Cooperation’. The fast and dynamically evolving interface between emerging economies and countries in Sub-Saharan Africa presents new challenges and potential opportunities across all channels of economic relationships. At the same time, the development experiences of the East Asian economies at large, which are at variance with the development model contained in the Washington and post-Washington consensus, provide some useful lessons for formulating a strategy for Africa’s future in the light of conditions prevailing in the latter.2

The changing landscape in aid relationships with the rapidly increasing engagements by emerging economies with low-income developing countries has also brought about a new dimension to the aid effectiveness debate as witnessed at the Fourth High-Level Global Forum on Aid Effectiveness (HLF4), held in Busan, South Korea in late 2011.3 The Busan conference was built on the Paris Declaration, 2005 and the Accra Agenda for Action, 2008. The Paris Declaration stipulates five principles on raising aid effectiveness: (1) Ownership: aid-recipient countries should forge their own national development strategies with their parliaments and electorates; in particular they should set their own strategies for poverty reduction, improve their institutions and tackle corruption; (2) Alignment: donors should support strategies set by recipient countries and use local systems; (3) Harmonization: donors should streamline their efforts in-country and coordinate, simplify procedures and share information to avoid duplication; (4) Results: development policies should be directed to achieving clear goals and for progress towards these goals to be monitored; Developing countries and donors shift focus to development results and results get measured, and (5) Mutual accountability: donors and recipients alike should be jointly responsible for achieving these goals; they are accountable for development results.

The Accra Agenda for Action further sets the agenda for accelerated advancement towards the Paris targets, proposing further three main areas for improvement: (1) Ownership: developing countries have more say over their development processes through wider participation in development policy formulation, stronger leadership on aid coordination and more use of country systems for aid delivery; (2) Inclusive partnerships: all partners – including donors in the OECD-DAC and developing countries, as well as other donors, foundations and civil society – participate fully; (3) Delivering results: aid should be focused on real and measurable impact on development.4

On paper, these are naturally laudable principles and action targets, on which no one could have disagreed with. With these objectives, the Busan conference of 2011 (HLF4) sought hard to bring in key new aid players from the Global South such as Brazil, China and India under one umbrella and set out a common framework on aid effectiveness, as it is widely recognized that ‘a new global partnership on development cooperation’ cannot be secured without the active participation of emerging market economies. However, in reality, the ways aid relationships have evolved between main traditional donors and recipient developing countries as well as the way the aid effectiveness debate has been conducted since the mid-1990s, led by the International Financial Institutions, cast long shadows on building trust and confidence between the donor community belonging to the OECD-DAC and the developing world.5

Today, we witness an ever-shifting world order with significant changes not only in political-economic power relationships but also in the global demographic composition in favour of developing nations. At the same time, all national economies have become truly integrated under globalization, benefiting from constantly evolving technological advancements. Yet, the market driven globalization process has also produced an ever-increasing skewed income and asset distribution globally. The global inequality has sharply risen recently as both ‘within-country’ and ‘between-countries’ inequality has increased in most countries of every continent. As clearly seen in the recent episode of the global financial crisis of 2008–9 and the subsequent ongoing sovereign debt crisis in the Euro zone, economic shocks originating in the US and Europe can propagate over the globe and be transmitted to the developing world at a strikingly fast speed. The possibility of ‘de-coupling’ national economies from events elsewhere is elusive, and at most temporary. In the ever-increasingly disequalizing world, it is often the poor residing in developing countries who bear the heaviest cost for the outcome of relentless global market forces and unregulated markets. The deteriorating eco-system resulting from climate changes also poses the greatest threat to food security of those most vulnerable in the world.6 The need to address these issues requires that the global community face up to these shared challenges with a view to lay down a foundation for sustainable development in all the key aspects, that is, to build a socially, financially and environmentally sustainable path for the global economy.

In this context, a fresh perspective and paradigm is required as a basis for designing the new global partnership on development cooperation in this millennium with much more participatory approaches and greater respect for different development models. The modality and roles of foreign aid should be discussed, and the debate on aid effectiveness should be reconstituted to fit the purpose of facilitating more inclusive development processes worldwide.

1.1.2 The scope of the book

Given the enormous challenges we face collectively as a global community, and the constantly shifting grounds in aid relationships, this book aims to contribute to the debate on how aid could assist development processes, in particular how aid could be a catalyst for developing local endogenous institutions in developing countries that can be both pro-growth and pro-poor. In this context, it is interesting to note that despite the universal acknowledgement that institutions do matter for development, there is little in-depth discussion and examination of the question of how aid can be a handmaiden and catalyst for local institution building in aid-recipient countries.

This is at least partly to do with the dominant and conventional position taken by policy makers and academics working in the institution–development nexus, who tend to assume that there is only one universally accepted set of institutions which are good for development and that such model institutions can be found in advanced donor countries. Consequently, discussions on the role of aid in institution development are often conducted from this particular position, arguing at least implicitly that institution development should involve convergence towards, or emulation of, the ‘best practice’ found in donor countries, as evident, for example, in dominant literature on ‘good governance and development’ (Acemoglu and Robinson 2008; Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi 2009; World Bank 1992).

We take a somewhat different position on the institutions-development nexus from prevailing conventional ones, arguing that: (i) institutions should be endogenously developed in a specific local context; (ii) institutions that are simply supplanted from outside without a careful adaptation to local environments are not sustainable over time as well as functionally ineffective; and (iii) socially and politically sustainable development involves institutional innovation for a local setting with clearly defined developmental objectives at hand.7 Once this is taken as a starting principle position, ‘donor countries’ cannot be a driver for development by setting the agenda and determining the course of development for ‘recipient countries’. Thus, in this mindset, the ownership of the blue-prints and the implementation of policy and institutional reforms should firmly rest with the recipient countries, and the donor countries can act as a mere ‘junior partners’ in the development processes, including institution building. In our opinion, foreign aid can be an important input into development efforts by domestic stakeholders if ‘development cooperation’ is well executed to meet their aspirations, but nevertheless it can play only the role of ‘handmaiden’ or ‘second fiddle’ in development processes.

Building on this common understanding of the role of aid in institution development shared among the contributors, this book attempts to explore the concept of ‘development cooperation’ as a distinctively different approach from the ones found in mainstream literature on ‘aid effectiveness’ for development.8 More specifically, we illustrate how this approach could be used for examining aid effectiveness in a broader context of institutional development of recipient countries through several case studies of aid-financed infrastructure development projects. Infrastructure projects are selected for illustrating our perspective of how aid can be a handmaiden for institution development for two reasons. First, infrastructure projects entail building not only physical infrastructure but also institutions for their sustainable service delivery. They could also have economy-wide, institutional spillover effects beyond the specific projects built. Second, as discussed below in detail, Japanese ODA has historically concentrated on economic infrastructure building in recipient countries, since ODA has been viewed as a ‘vanguard’ of foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade expansion, and aid has been channelled for providing ‘public goods’ private investors and actors with the necessary economic infrastructures. From this specific perspective, and exploiting rich experiences in the field and practical knowledge gained by the authors of the case studies through their development work in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa for Japan’s governmental aid agencies, this book will, we hope, make a valuable contribution to the literature and the policy debate on aid effectiveness more generally.

In particular, this volume presents detailed analyses and discussions in the following three areas: (i) institutional evolution in developing countries, with particular reference to the roles of endogenous institutions; (ii) comparison of donor – recipient relationships between East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa; and (iii) policy lessons drawn from East Asian experiences of infrastructure building for governments in Sub-Saharan Africa, the international aid community, and emerging development partners from the South, including China.

It may be pertinent to recall here that Japanese bilateral official assistance to developing countries in Southeast Asia has been provided in ‘the framework of Economic Cooperation’ rather than ‘giving aid’.9 China was the largest recipient of Japanese bilateral aid from the late 1970s until recently, and the Chinese assistance to developing countries today is often seen to be modelled on the successful Japanese experiences of providing assistance to developing countries in Asia, including China. However, in reality there are both significant similarities and critical differences between the Japanese and Chinese approaches and practices in the delivery of assistance on the ground in recipient countries, as elaborated further below as well as in Section 1.2.2 of this chapter and Chapter 2. Concrete evidence for similarities and differences can be found in the case studies of Japanese aid presented in the book.

We also suggest that this book can offer a unique perspective on the development of institutions in several key aspects. First, in other works of literature that deal with institutional evolution or capacity building in developing countries, the majority of researchers discuss these issues through the lenses of ‘donors’. Accordingly, they tend to focus on the effect of technical or institutional transfer from ‘donors’ to ‘recipients’, and as a rule they do not pay due attention to existing local institutions and the impact of endogenously evolving changes of institution as development proceed in recipient countries. However, as North (1990) recognizes, informal institutions embodying cultural heritages and norms are very critical in shaping institutions. He examines how informal institutions, which could act as ‘informal constraints’ for moderniza...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Institutional Evolution through Development Cooperation: An Overview

- 2 Shifting Grounds in Aid Relationships and Effectiveness Debate: Implications for Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

- 3 The Eastern Seaboard Development Plan and Industrial Cluster in Thailand: A Quantitative Overview

- 4 The Eastern Seaboard Development Plan of Thailand: Institutional Aspects of the Challenges and Responses

- 5 ODA and Economic Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of the Transfer of Intangible Resources

- 6 Brantas River Basin Development Plan of Indonesia

- 7 Institutional Comparative Study of Brantas (Indonesia) and Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) and Its Policy Implications

- 8 China: From an Aid Recipient to an Emerging Major Donor

- Index