- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With Asia as its backdrop, this book investigates the role played by the World Bank Group (WBG) in conceptualising and promoting new mining regimes tailored for resource-rich country clients. It details a particular politics of mining in the Global South characterised by the transplanting, hijacking and contesting of the WBG's mining agenda.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Regimes of Risk by Pascale Hatcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Into the Deep: The World Bank Group, Mining Regimes, and Theoretical Insights

‘No frontier is too far or too difficult’

International Financial Corporation (2009a, p. 9)

This chapter details the historical role played by the World Bank Group (WBG) in fostering new regulatory mining regimes in the Global South, and the theoretical insights that have influenced such regimes over time.

The exercise follows the first two objectives that guide this book. It allows for the study of the different strategies adopted by the WBG for the mining sector of its country clients over time in order to better understand the new generation of regulatory regimes it has now developed for the mining sector. Such a historical analysis further allows for the argument that any evaluation of the WBG’s overarching influence over the sector needs to take into account the cumulative impact of the liberalisation and deregulation policies led by the Bank over the course of the last three decades, as well as the influence of the International Financial Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) in catalysing foreign investments for resource-rich countries of the Global South. In turn, this allows for the argument that while the extractive industry represents only about two per cent of the Group’s total financing (World Bank, 2012f, p. v), the institution’s influence extends far beyond the numbers in its portfolio and therefore, cannot be overstated.

This historical analysis of the WBG also serves to shed theoretical light on what is here referred to as the Social-Development Model (SDM) and its emergence. While this more recent involvement of the Group in the sector has been geared towards the positive socio-economic impacts that mining may have on resource-rich countries, it will become clear that the actual safeguards and policies promoted by the Group are falling seriously short of addressing the highly contentious nature of the particular politics of mining enshrined within the new regimes. Building on legal pluralist and critical political-economy insights, the chapter analyses the WBG’s model for the sector and lays the theoretical foundation for the three cases studied later in this book. This theoretical framework allows us to shed new light on the SDM, which is here seen as a social risk-management tool by means of institutional engineering and market reforms. This technocratic take, which favours factions of capital engaged in mining activities, explains how local communities, who have been promised socio-economic benefits and environmental safeguards, are left with mixed benefits at best.

This chapter is divided into four steps. First, the specific role of the World Bank, as well as each of its private arms, IFC and MIGA, in the extractive industry will be detailed, notably in relation to the concept of ‘risk’. This will be followed by a historical assessment of the specific role played by the WBG in redefining mining regimes in reforming countries. It will be argued that the WBG has recently and significantly transformed its image by adopting the SDM, a model which notably leads to approaches seeking to engage local stakeholders in participatory schemes, new ‘partnership’ initiatives between the private sector and civil society, as well as new monitoring responsibilities assigned to both the state and the private sector. In the third part, the transformation of the roles and responsibilities assigned to these different stakeholders will be assessed in light of the new social-development narrative. It will become apparent that if the immediate investment risks faced by neoliberal interests have successfully been addressed by the Bank’s renewed presence in the sector, the very regulatory functions of the state have been reassigned to the local level. Crucially, this process has relegated the management of poverty alleviation and environmental safeguards to the local level, leaving isolated communities with the burden of negotiating with mining corporations and local authorities looking for profits. As such, much like earlier incarnations of neoliberalism in the mining sector, the promotion by the WBG of this new SDM continues to cause serious repercussions for constituents in the underdeveloped world, bringing into question the legitimacy of the model itself.

Towards the last frontier: mining, risk investments, and the World Bank Group

Whereas the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA) work solely with governments, IFC and MIGA work with the private sector. Hereafter in this book, the IBRD and IDA will be referred to as ‘the World Bank’ or ‘the Bank’ and the latter’s private arms, IFC and MIGA, will be referred by name. When discussing all four actors belonging to the WBG,1 an explicit reference to the Group will be made. Figure 1.1 shows each arm of the WBG.

Alongside the World Bank, which has played an historical role in designing and fostering new regulatory mining regimes across the Global South, MIGA and IFC have played important and complementary roles in opening up new markets, especially in mining. The Bank is responsible for country policy dialogue and tends to centre its efforts on broader structural and social issues, including sector policy reform and institutional capacity building. IFC focuses on attracting private sector investment, while MIGA specialises in providing political risk guarantees.

Figure 1.1 The World Bank Group

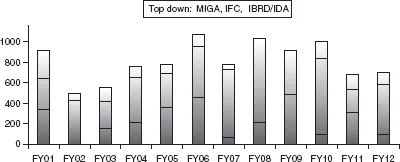

Figure 1.2 WBG extractive industry financing (FY 2001–2012)*

*In millions of US$.

Source: World Bank (2012f, p. 7).

In 2012, the Group’s financing of the mining sector reached US$695.5 million (World Bank, 2012f, p. v). Figure 1.2 shows extractive industry financing for the WBG’s respective arms from 2001 to 2012.

Alongside its affiliates, the World Bank has been focusing on the broader structural issues of its country clients, notably sector policy reform and institutional capacity building. In the fiscal year 2012, the institution’s financing of the mining sector accounted for US$85 million (World Bank, 2012f, p. 8). However, this number may be misleading, as most of the Bank’s financing is part of larger programmes, namely governance and transparency programmes.

The scale of the World Bank’s overarching influence over the liberalisation and deregulation of the mining sector in poor indebted countries over the better part of the last three decades should not be understated. It is worth recalling that the Extractive Industries Review (EIR), which was established in 2001 to independently evaluate the WBG’s involvement in extractive industries, estimated that under the distinct leadership of the Bank no less than 100 countries reformed their laws, policies, and institutions during the 1990s (2003a, p. 10). While the actual theoretical underpinnings of these new policies are the topic of the following section, it is crucial for now to note that the EIR further stressed that ‘in line with WBG advice’, these new legislations, which were designed to ensure the protection of capital and to promote investment, successfully brought many developing countries to experience an investment boom in their mining, oil, and gas sectors (2003a, p. 13).

Additionally, any evaluation of the weight of the WBG’s influence over the mining sector should encompass IFC, which holds a mining portfolio of US$500 million,2 and MIGA, whose own portfolio currently stands at US$240 million (MIGA, 2013a). This represents approximately 3.2 per cent of IFC’s oil, gas, and mining portfolio and 2 per cent of the MIGA’s outstanding gross mining portfolio (11 per cent if we account for its entire extractive industry portfolio).3

Established in 1956, IFC is the private sector’s lending arm of the WBG. It is a for-profit organisation which aims to support the growth of the private sector in developing countries. It does so primarily by financing private sector investment, mobilising capital in international financial markets, and providing advisory services to businesses and governments (IFC, 2009b) – see Table 1.1. With a net income of US$1.3 billion in the fiscal year 2012 (IFC, 2012a, p. 25), IFC is the largest multilateral financial institution investing in private enterprises in emerging markets. The organisation disbursed close to US$12 billion in 2012 alone (IFC, 2012a, p. 25), almost a third of the entire WBG budget. By June 2011, IFC had 37 mining projects4 in 25 countries (IFC, n.d.)

MIGA’s core mission is to promote foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries. Its main activities are providing political risk insurance against certain non-commercial risks to investments in developing countries (see Box 1.1 for details). Additionally, the Agency offers technical assistance such as capacity building and advisory services to help countries attract FDI,5 as well as dispute mediation services6 in order to reduce future obstacles to investment. Since its inception in 1988, MIGA has issued nearly 900 guarantees worth more than US$17.4 billion for projects in 96 developing countries (MIGA, 2009a).

Table 1.1 IFC mining activities

Investment areas | Financial products | Advisory services |

|---|---|---|

Exploration | Equity | Supplier development |

Development | Quasi-equity | Community development |

Expansions | Loans | Municipal capacity building |

Financial restructuring | Capital markets access and mobilisation | Environmental and social advice |

Rehabilitations | Resettlement and indigenous peoples |

Source: IFC (2013d).

Box 1.1 MIGA: types of coverage

Expropriation coverage for sovereign and sub-sovereign risk protects against discriminatory administrative or legislative actions by governments at both national and subnational levels that may result in nationalisation and confiscation. Expropriation guarantees also protect against a series of acts that gradually lead to expropriation – such as changes in licensing or royalty agreements – or burdensome administrative procedures.

Customised breach of contract coverage when governments are contractual partners can be designed to target specific mining-related concerns such as the revocation of leases or concessions, as well as tariff, regulatory, and credit risks arising from a government’s breach or repudiation of a contract.

Coverage against currency-related risks protects investors against losses from an inability to convert local currency into foreign exchange for transfer outside the host country. Even when governments impose a moratorium on moving currency, as shareholders of MIGA, they may agree to exclude MIGA-insured projects and permit the transfer.

Non-honouring of sovereign financial obligations coverage protects against losses resulting from a government’s failure to make a payment when due under an unconditional financial payment obligation or guarantee given in favour of a project that otherwise meets all of MIGA’s normal requirements.

Coverage against war, civil disturbance, terrorism, and sabotage protects against physical damage and prolonged business interruption. Coverage extends to situations in which an investor is forced to abandon the project due to war or other political disturbance. In such cases, assets need not be damaged or destroyed for a claim to be made. In addition, while border closures or blockades might not cause destruction, they can significantly interrupt business activities; MIGA guarantees can cover associated losses. Coverage for temporary business interruption, including both costs and lost net income, is also available.

Source: Adapted from MIGA (2013b).

However, the WBG’s influence in the extractive industry extends far beyond the mere numbers in each arm’s respective portfolio. Both the Bank and its affiliates are materially and ideologically incentivised to get projects going and instil profit-oriented regimes and projects. The multilateral agency’s ‘loan culture’,7 in which portfolio managers are institutionally encouraged to disburse, remains omnipresent, even in the extractive industry. While the controversies linked to extractive industry investments have led to more cautious lending practices, the ultimate purpose of organisations such as IFC and MIGA remains to enhance and open new spaces of accumulation. In fact, the significant influence of these organisations extends not only to their respective ability to catalyse private investments, but to countries and sectors that pose heightened ‘risks’ as well.

The concept of ‘frontier markets’ is here crucial. It refers to an IDA eligible country, a ‘fragile state’,8 or a ‘frontier region’9 in a middle-income country (Bretton Woods Project, 2011a). It is to be noted that the three cases presented in this book – the Philippines, Laos, and Mongolia – all qualify as frontier regions. Laos is an IDA country, while the conflict-stricken region of Mindanao in the Philippines, one of the richest regions in terms of mineral reserves,10 easily qualifies as a frontier region. The term also applies to Mongolia, where the largest mines are located in the middle of the Gobi Desert.

Foreign investors often hesitate to invest in risk regions and as such, the WBG’s power to galvanise investments in these environments is tremendous. In other words, the multi-front and complementary roles played by each arm of the Group have been highly successful in opening new markets in frontier environments such as mining, which is specifically defined as a high-risk sector. Consequently, the extent of the influence of the Bank’s affiliates over the mining industry can further be understood by their respective ability to act as catalysts for private sector investments in countries and sectors that pose a heightened risk to investors. For example, since its inception MIGA has issued a total of US$11billion in coverage while it further facilitated an estimated US$47 billion in FDI (Bray, 2003, p. 324).

What is crucial to emphasise is that the WBG entices investments into sectors where they might not have existed without the presence of the Group: ‘In places where the poor might otherwise be left behind, we play a catalytic role’, states IFC (2008, p. 33). However, and as illustrated in details with each cases presented in this book, the social, environmental, and economic impacts of promoting large-scale mining activities in such countries are significant. While wholeheartedly linking such impacts to the action of the WBG would be unfair, there is an important case to be made for probing the influential role of a public multilateral institution in promoting activities for which the devastating social and environmental impacts are indisputable, most especially in ‘frontier markets’ where the state’s ability to monitor and enforce socio-environmental provisions is known to be weak.

IFC’s Operations Evaluation Group (OEG) found that the Corporation played a catalysing role in the extractive industry, often being the very first private investor in the sector (OEG, 2005, p. 115).11 While present in more than 130 countries, in recent years ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables, Maps, and Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Into the Deep: The World Bank Group, Mining Regimes, and Theoretical Insights

- 2 The Open Pit: Socio-Environmental Safeguards, Multilateral Meddling, and Mining Regimes in the Philippines

- 3 Mining, Multilateral Safeguards, and Political Representation in Laos

- 4 Green Mining in the Gobi? Multilateral Norms and the Making of Mongolia’s Mining Regime

- 5 Fighting Back: Resource Nationalism and the Reclaiming of Political Spaces

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index