eBook - ePub

Science and Innovations in Iran

Development, Progress, and Challenges

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Science and Innovations in Iran

Development, Progress, and Challenges

About this book

This comprehensive book examines the Iranian government's mobilization of resources to develop science and technology, presenting an overview of the structure, dynamics, and outcomes of the government's science and technology policies. Authors are leaders in the industries they discuss and offer an unparalleled look into Iran's technology sector.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Science and Innovations in Iran by A. Soofi, S. Ghazinoory, A. Soofi,S. Ghazinoory in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Introduction

Developing economies often achieve industrial development and catch up technologically in normal development circumstances through the acquisition of foreign technologies by means of mechanisms such as purchasing equipment from abroad, licensing, subcontracting, engaging in foreign direct investment, hiring foreign experts, participating in joint ventures and the formation of strategic alliances, manufacturing original equipment, and purchasing foreign enterprises outright. However, under the conditions of international sanctions and limited interactions with technologically advanced countries, many of these approaches are not readily available for countries facing economic sanctions. Iran, of course, is confronting such sanctions, and cannot use many of the stated mechanisms listed above to transform its industry. Therefore, the country must rely on its own physical and manpower resources as well as the ingenuity of its citizens for technological advancement.

Moreover, it is widely known that even under normal conditions of development, many emerging economies, even though they may successfully adopt and imitate foreign technologies, face formidable barriers and challenges in moving beyond imitation and becoming innovators. Iran is no exception in this regard. Accordingly, Iran faces two sets of challenges in resolving its latecomer status in the technological arena.

This book is an attempt to gain an understanding of how Iran is coping with these two sets of constraints on the path to its industrial transformation, how successful it has been, and what challenges it faces in achieving its developmental objectives.

In this introductory chapter, we will examine the broad theoretical framework of the industrial transition of emerging economies as a guide for evaluating the industrialization processes in Iran. This theoretical discussion, along with Iran’s experiences in technological-industrial development, will allow the reader to gain an understanding of whether the country has followed and is following the guidelines, which are based on the experiences of the newly industrialized economies (NIE) of East and Southeast Asia. Moreover, we will delineate the current state of technological development in Iran, and based on a review of the chapters in this volume, discuss the country’s efforts in overcoming the technological challenges it faces.

Coordination Failures: Market and Government

This study, to a large extent, is concerned with the industrial development policies and practices of different administrations in Iran since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, with particular emphasis on the 1990–2010 period. These policies are tantamount to the coordinating activities of the government in the country. Since private property is the dominant form of production relationship in the country, and since most exchanges are mediated by means of markets, the prominent role of the government in the process of the industrialization of the economy implies the failure of the markets to coordinate economic activities. However, coordination failures, in the sense defined below, are so pervasive in the Iranian economy that one could reasonably attribute the failures to both the government and the market. Therefore, defining economic coordination is of paramount importance.

Economic coordination refers to a “pleasing” arrangement of economic activities. For example, Klein (1997) states: “Coordination . . . is best understood as something we hope to achieve in our interaction with others.” Viewing economies from this perspective, one could consider an economy with full-employment output successful; therefore, a full-employment level of output is deemed to be the result of a coordinated economic system. Or, based on this definition, one would conclude that coordination is a failure (market, government, or both) in a depressed economy, where markets for labor, capital, and goods do not clear, and excess supplies emerge.

The second definition of coordination is a mutual meshing of activities, and in the economic context, one would consider market clearance as a coordination activity, or market disequilibrium as a coordination failure.

Traditionally there were two opposing views on the role of the government in developmental processes: the market-friendly view and the developmental-state view. The market-friendly view holds that most, if not all, coordination activities in an economy are best performed by the market mechanism. Government intervention in the marketplace, according to this view, should take place only in cases of market failure. Furthermore, the market-friendly view states that even under the best of circumstances where the government successfully coordinates a particular project, it blocks market-coordination over the long run, and hence makes sustainable coordination impossible (Matsuyama 1996). The developmental-state view, in contrast, perceives market failures in developing economies to be pervasive and looks to government to remedy these failures (Aoki, Kim, and Okuno-Fujiwara 1996).

A third view, as presented by Aoki and colleagues (1996), departs from the neoclassical economic theory, which predicts that competitive markets tend to allocate resources optimally, and argues that governments can “enhance” market performance, thus implicitly rejecting the market as the optimal resource allocation mechanism. This is called the “market-enhancing” role of government (Aoki, Kim, and Okuno-Fujiwara 1996).

In the literature dealing with the “Asian Miracles,” where the term “miracle” refers to the rapid industrialization of the East Asian economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore (NIEs), the same controversy regarding the preeminence of the state versus the market in the developmental process emerged also. The proponents of the primacy of the state in the industrial development of these economies include Kim and Dahlman (1992), and Amsden (1989), while those who believe that after the initial government-led coordination, firms and by implication, the markets take control of coordination and play a more important role in the coordination process include writers such as Hobday (1995), Hobday, Cawson, and Kim (2001), and many other scholars.

The historical experiences of many newly industrialized countries of East and Southeast Asia, as well as the important role of the Iranian government in the country’s economy, as documented by the chapters in this book, give substantial support to the “market-enhancing” view of the role of the state in economic development, and we uphold this view in the present volume.

Setting the macroview of debate on the relative importance of state versus market coordination aside, we find the examination of the patterns of development of successful industrial enterprises in East Asia during the last three decades insightful and illuminating. We examine two important contributions in this field of inquiry: Hobday and colleagues (2001) and Lee and Lim (2001). These authors critically reviewed the transformation of several local firms in South Korea and Taiwan, and showed how these enterprises, as latecomers, were able to acquire technical and marketing competencies and become globally competitive.

Hobday (1995) classifies firms as “leader” “follower,” or “latecomer.” Technology leaders are innovative firms that operate in markets with an advanced technological infrastructure and develop new products and processes. Follower firms are directly connected to the advanced markets; however, their technology lags behind that of the leaders. Nevertheless, they have the opportunity to learn from the existing technologies, improve upon them, and even become leaders in their own right.

The leader-follower classification of firms characterizes firms that operate in the national system of innovation in advanced industrial economies. A different class of firms that is often encountered in the developing economies is called the “latecomer” firm. Latecomer firms face two formidable technological and market-access challenges they must overcome if they wish to succeed globally.

Being located in developing countries, the latecomer firms are isolated from the main centers of technological development, have little or no access to distinguished institutions of higher learning, operate in business environments with poorly developed technological infrastructure, are behind in engineering skills, and cannot initiate meaningful, effective research and development (R&D) projects. In most developing economies, the marketing problems faced by these latecomer firms include small domestic markets, which cannot provide the opportunities for the firms to achieve economies of scale, and high barriers to entry into the foreign markets that enjoy high demand (Hobday 1995). To be globally competitive, firms in the developing countries must overcome these technological and marketing barriers.

According to Lee and Lim (2001), not all latecomers follow the same path of evolution to follower and leader status, however. Some latecomers skip the developmental processes, perhaps creating their own pattern of evolution that is different from that of their forerunners. Studies have shown that not all industries within a newly industrialized economy or the same industry in different countries has followed the same path. It is even possible to observe the heterogeneous development of industries within a country.

Furthermore, analysis of the industrial development of successful latecomer firms has indicated that, in general, these firms in the emerging economies go through three phases, starting with original equipment manufacturing (OEM), moving to own design manufacturing (ODM), and from there entering into own brand manufacturing (OBM).

OEM refers to subcontracting where a foreign buyer (often a transnational company) provides the detailed technical specifications to the latecomer firm for manufacturing the product. In an ODM system, the latecomer both designs and manufactures the product, and then sells it as OEM. Finally, in an OBM system the latecomer has developed the capability of designing, manufacturing, and marketing to challenge the leader and compete globally (Hobday 2001).

These broad discussions relating to the relative roles of the state, markets, and firms in the developmental processes in NIEs over the last five decades provide a framework for us to examine and assess the role of the state, markets, and enterprises in the evolution of the Iranian economy.

First, it should be noted that three classes of enterprises exist in Iran: state-owned enterprises (SOE), cooperatives, and private enterprises. In the manufacturing sector, the SOEs play the most prominent role among the three. Accordingly, the state in Iran must adopt those policies that remedy both the coordination failures of private and cooperative firms, through direct and indirect measures, as well as address the coordination failures of SOEs, which have the responsibility for managing the government-owned firms and for acting as the governing bodies of enterprises.

Second, since the Iranian government is deeply involved in the design and implementation of industrial as well as science and technology policies for industrial development, we need to define industrial development, industrial policy, and science and technology policy in order to have a better understanding of the analyses that appear below and in the succeeding chapters of this book.

First, “industrial development” is defined as “a process of acquiring technological capabilities . . . ” (Kim and Dahlman 1992, 437). Next, Kim and Dahlman (1992, 437) define science and technology policy as “a set of instruments the government uses in promoting and managing the process and direction of acquiring such capabilities.” Accordingly, we consider technology policy as a set of direct and indirect governmental policies that affect scientific and technological development. The direct policies define the direction and pace of the supply side of technological development by creating and strengthening technological capabilities. This is commonly known as science and technology policy. The indirect policies may be divided into two subcategories. The first subcategory involves a set of policies that affect the demand side of technological development by creating the need for technological capabilities through financial and tax incentives to firms. The second subcategory consists of a set of policies that facilitate coordination (in the sense defined above) by creating conditions that ensure the smooth functioning of the market for technologies. The indirect policies are referred to as industrial policy.

The Role of State and Market in the Successful Industrial Transformation of Enterprises

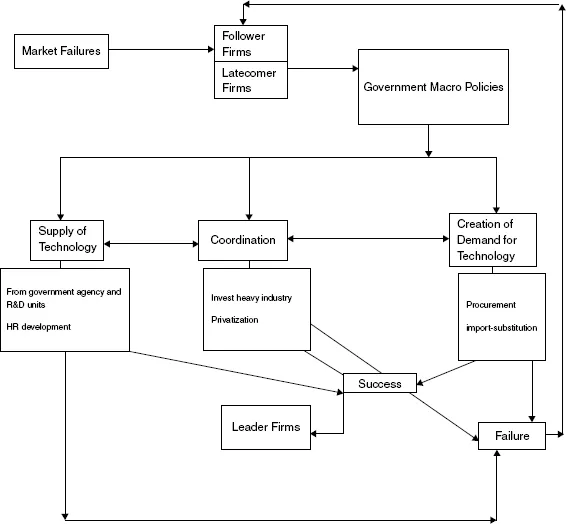

Figure 1.1 is the flow chart of interactions between firms and the state in the process of industrialization. Coordination failures by the market lead to the latecomer/follower status of firms. The government’s attempt to remedy market failures by taking policy measures to supply technologies, induce private or state-owned enterprises to demand technologies, and to adopt policies to clear the markets for technologies can lead to either success or failure. The government’s failure to achieve its objectives leads to the status quo for latecomer/follower firms. In contrast, government success leads to leadership status of the latecomer/follower firms, which is tantamount to industrial transformation and progress.

Figure 1.1 Coordination Failures and Government Remediation.

What are the specifics of supply-side, demand-side, and coordination policies? What specific policy measures could governments use to remedy market failures, which have resulted in the formation of latecomer/follower firms? Even though many policies have been adopted by governments of the NIEs over the past 40 years, we state a sample of measures in each category that have been used in the past, particularly in South Korea. It should be noted that by no means is the list exhaustive.

(i) Policies to induce demand for technologies by latecomer firms

Measures to induce demand for technology include government procurement of products and services; import-substitution policies; government policies to reduce market power and enhance competition; export-promotion policies; industrial policies to strengthen target industries (e.g., imposing quotas, import licensing, domestic content requirements, offering tax incentives, preferential financing, loan guarantees, and R&D subsidies in the form of government-corporate research for those who produce the designated products); and protection of intellectual property rights. Moreover, establishment of a central agency to coordinate the technological activities of all ministries of the government would have both supply-and-demand effects in building technological capability.

(ii) Policies to supply technologies to the private sector

This set of policies can be divided into direct and indirect policy instruments. Direct policy instruments include the creation of a central government agency, such as a Ministry of Science and Technology, to coordinate the technological activities of other ministries, and establish R&D organizations. Indirect policies consist of investment in human resources; import-substitution; restricting technology transfer and foreign direct investment (FDI); promotion of turnkey plants and the import of capital goods in the early stage of industrialization; lifting of the restrictions on FDI and foreign technology transfers at a later stage of the development; export promotion; and import of foreign capital. Moreover, governments have established highly specialized research institutes and firms as spin-offs from earlier public research institutes to develop in-depth capabilities in targeted industries.

(iii) Coordination policies

Coordination policies that are used include the creation and promotion of the heavy industries (steel, chemicals, and metal cutting machinery, shipping, other means of transportation, and infrastructure); policies to achieve economies of scale, like Chaebols (large conglomerates) in South Korea; development of “strategic industries”; privatization of SOEs; allocation of credit to select industries; a preferential exchange rate for use by large enterprises; state guarantee of foreign loans borrowed by Chaebols, for the import of turnkey factories for import-substitution industries, and supplying low-interest-rate loans to firms with losses due to foreign currency exposure; further licensing of successful Chaebols, the penalizing of poor performers by not supporting them and allowing them to fail; and the granting of licenses in lucrative industries to those enterprises that are willing to invest in riskier sectors. Other coordination (linkage) policies used in South Korea include tariff exemptions on capital goods; low interest-rate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Editors’ Preface

- Foreword

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The History of Science in Iran from a Physicist’s Perspective

- 3 From Developing a Higher Education System to Moving toward a Knowledge-Based Economy: A Short History of Three Decades of STI Policy in Iran

- 4 The National Innovation System of Iran: A Functional and Institutional Analysis

- 5 Information and Communication Technology: Between a Rock and a Hard Place of Domestic and International Pressures

- 6 Nanotechnology: New Horizons, Approaches, and Challenges

- 7 Biotechnology in Iran: A Study of the Structure and Functions of the Technology Innovation System

- 8 Nuclear Technology: Progress in the Midst of Severe Sanctions

- 9 Iran’s Aerospace Technology

- 10 The Automotive Industry: New Trends, Approaches, and Challenges

- 11 Conclusion

- List of Contributors

- Name Index

- Subject Index