eBook - ePub

Fertility Rates and Population Decline

No Time for Children?

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fertility Rates and Population Decline

No Time for Children?

About this book

While many worry about population overload, this book highlights the dramatic fall in fertility rates globally exploring questions such as why are parents having fewer babies? Will this lead to population decline? What will be the impact of a world with fewer children and can social policy reverse fertility decline?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fertility Rates and Population Decline by A. Buchanan, A. Rotkirch, A. Buchanan,A. Rotkirch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

What Is Happening to Fertility Behaviour?

1

No Time for Children? The Key Questions

Ann Buchanan and Anna Rotkirch

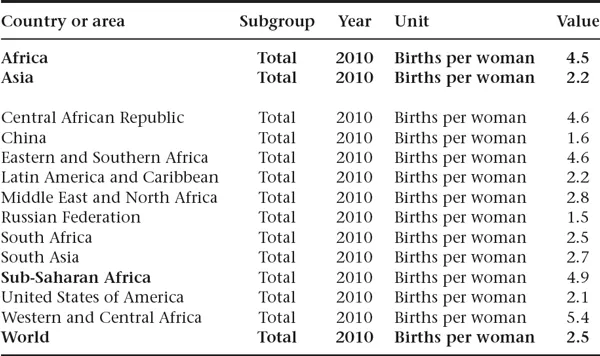

While many are concerned about global overpopulation and its impact, this book takes another view. Silently, with little fanfare, a dramatic change is taking place: people are having fewer children. The UN World Fertility Patterns (2007) note that in the world the total fertility rate (TFR), or the lifetime number of children women are calculated to have, has declined from 4.5 in 1970–75 to 2.6 in 2000–05. In 2010 it was 2.5 (see Table 1.1). The decline affects all regions of the world, but it started in Europe where, in all but three countries, the TFR has fallen below two. In recent years, a particularly dramatic decline has been seen in some Asian countries.

The main focus of this book is the reasons for declining fertility rates across the globe and the possibility of population decline. The secondary focus is that in a world with fewer children it will be important to maximize the potential of all children, including those who stayed at the margins of society in the past. Children will become a nation’s most valuable asset in maintaining and sustaining economic well-being. Childbearing is a complex phenomenon, which has been approached from varying angles by different scientific disciplines. Typically, demographers describe what is going on, psychologists study individual motivations and well-being and the social scientist analyses the structures, norms and policies that link micro and macro levels. This book engages insights from all these disciplines to provide a comprehensive and accessible overview of the what, why and how in contemporary childbearing behaviour.

Table 1.1 Total fertility rate (children per woman)

The State of the World’s Children (2010); United Nations Population Division.

Source: Derived from UN data. Population Statistics, 2011.

The key questions

First, what is happening to fertility rates across the world? How low is the current fertility decline likely to go, and why is fertility modestly growing again in some countries? How is the increase in childlessness and the one-child family shaping fertility trends?

Next, why are parents having fewer children? Is it because, with the availability of contraception and careers, women have more choices, or are economic and policy constraints impinging? Case studies around the world give differing perspectives.

Thirdly, what will be the consequences of lower fertility rates? If indeed lower fertility means smaller populations, what will be the impact on adults and children? What is happening to less fortunate children who in some cases lack any effective parenting? Since the relations and obligations between generations affect childbearing, we also consider the effect of the growing number of elderly. To what extent can and should the older generation fill the parenting gap in time-poor societies? Will adults be willing to take care of their parents, and will this conflict with their own childbearing? In many parts of the world, particularly in Confucian societies, it is a moral imperative for the younger generation to provide for their parents, sometimes so that one of them renounces the opportunity to have a family of his or her own. Finally, we ask social policy scholars how we should respond to a world with fewer children. Can policy initiatives influence parental ambivalence about having babies by giving them more help? How can we make more time for children and improve their well-being?

What is happening to fertility rates?

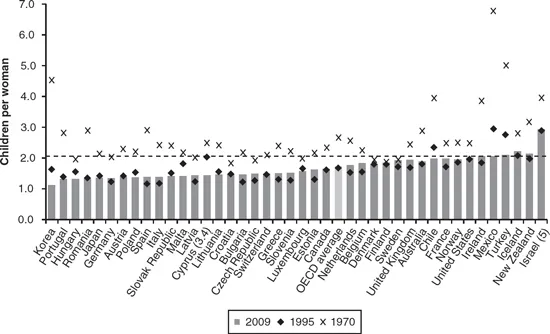

In Part I, the demographers discuss the implications of the raw facts given here. If we look at data across the developed world we see dramatic changes. The following chart (Figure 1.1) highlights the decline in fertility across the industrialized countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The dotted line plots the level that is theoretically necessary for a population to replace itself. That is, on average, two people need to produce just over two children (allowing for mortality). Figure 1.1 shows that in 2009 TFRs were well below the replacement rate in most countries, but exceeded two children per woman in Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Turkey and the United States. Particularly, dramatic drops can be seen in Mexico, Turkey and Korea between 1970 and 2009.

However, while no country had higher fertility in 2009 than in 1970, a few have higher levels now than they did in 1995. In the last census, the UK Fertility Rates were the highest since 1972. In 2010, the census reported a TFR of 1.98. This was felt to be due mainly to increases in the numbers of foreign born women as well as some mothers who had previously delayed having children completing their families (ONS 2011). Indeed, many European societies appear to have reached the end of the almost uninterrupted fertility decline they have experienced for over a century. The most developed countries, like the United Kingdom, are exhibiting a modest rise in fertility today and may be approaching replacement levels (Myrskylä et al. 2009). Many believe that this surprising turn in fertility decline is related to gender equality and family policies facilitating both women’s wage work and parenthood. Although the evidence is mixed, long-term, family-friendly policies do appear to boost fertility at least above very low levels (Bradshaw and Attar-Schwartz 2010, pp. 185–212; Gauthier – chapter 16; Rønsen and Skrede 2010). However, shifts in TFRs are also influenced by changes in the timing and spacing of children. Since women are having children increasingly later in life, postponement of births may create a gap between estimated fertility rates and actual childbearing (Billari et al. 2006). The actual number of children born to any generation, or completed cohort fertility, can be known only after women have reached the end of their childbearing years. Thus we cannot yet tell for sure to what extent fertility rates have really stopped declining in some countries.

Figure 1.1 Total fertility rates (TFRs) in 1970, 1995 and 2009

Source: OECD Family Database (2010a).

Looking more widely across the world, TFRs are dropping below the replacement level in many countries. Higher fertility rates are seen mainly in Africa. Table 1.1 looks at a broad range of fertility rates across the globe. The highest rate shown is in sub-Saharan Africa.

Average fertility rates conceal the polarization of childbearing between different families. The proportion of childless people is growing in most societies. In some nations, such as Germany or China, the one-child family is an increasingly popular choice. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom, TFRs are rising because more parents are choosing to have three or four children.

Within countries, there are significant differences in fertility rates between ethnic groups. For example in the United States, since 1980, fertility rates have been relatively stable, remaining between 64 and 71 births per 1000 women but in the last few decades, fertility rates have declined substantially among non-Hispanic blacks and among American Indian and Native Alaskan women. Fertility rates have declined slightly overall among non-Hispanic whites, but have increased among Hispanics (Child Trends DataBank 2007).

Immigrant workers who have just arrived in a country have, as we have recently seen in the United Kingdom, an important impact on TFRs. In Scotland, for example, the proportion of births to non-Scots born mothers has increased from 13 per cent in 1977 to 24 per cent in 2009. In recent years (from 2004 to 2007) Scots-born mothers accounted for 40 per cent of the increase in births, other UK-born mothers a further 5 per cent of the increase, while mothers born elsewhere accounted for 55 per cent of the increase. However, research suggests that the fertility behaviour of migrants tends to converge with that of the resident population over time (Scottish Government 2010).

Population statistics are fraught with controversies. The demographers in Part I of this book will argue these various viewpoints.

What difference does contraception make?

One of the key drivers to declining fertility is, of course, the availability of contraception. While in the past women spent most of their lives rearing the next generation and caring for the family’s vulnerable members, the arrival of reliable methods to control fertility meant, for the first time, that women were freer to consider a life outside the home.

Although attempts to control fertility date back to the earliest times in China, ancient Greece and Rome, it was not until the twentieth century that the first birth control clinics were set up for married women. In 1910, only 13 per cent of English married couples used birth control; however, by 1982 in the United States nearly 70 per cent of married couples practised birth control (Quarini 2005).

Contraception use is strongly affected by religious and moral beliefs. The aim of the early pioneers, such as Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger in the United States, was to alleviate poverty and improve women’s health. But access to contraception will not automatically translate into contraceptive use, even among poor women. Behavioural ecologists have shown how strongly contraceptive uptake can differ even between neighbouring villages and how it is mediated by broader changes in well-being and women’s life course (Mace and Colleran 2009). The fascinating social and psychological variation of contraceptive use is further analysed by Barber in Chapter 7, Young Women’s Relationships, Contraception and Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, of this book.

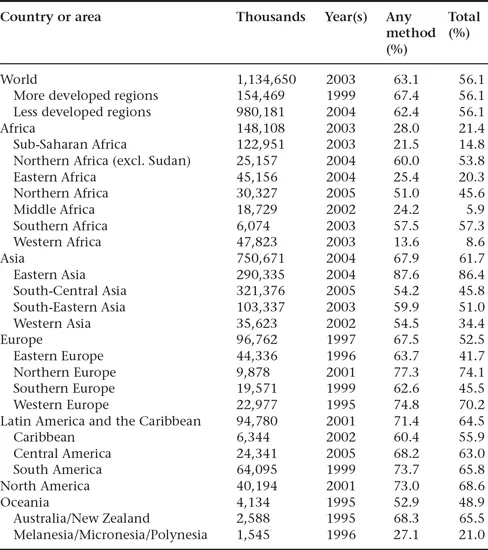

Table 1.2, derived from UN statistics, gives an overview of the availability of contraception globally in 2007. The extremely low rates of availability are particularly notable in parts of Africa and Melanesia.

It is interesting that although declining fertility rates reflect the availability and use of contraception, the proportion of unwanted pregnancies remains high. An estimated 41 per cent of all contemporary pregnancies worldwide and 44 per cent in Western Europe are thus reported to be either mistimed or unwanted (Singh et al. 2010).

Table 1.2 United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Contraceptive Use 2007

Source: Derived from United Nations (2008)

In some areas abortion is used as a means of controlling fertility, and this is not recorded in Table 1.2. Obtaining accurate data on the number of induced abortions is difficult. However, it is estimated that approximately 26 million legal and 20 million illegal abortions were performed worldwide in 1995, resulting in a worldwide abortion rate of 35 per 1000 women aged 15–44. Eastern Europe had the highest abortion rate (90 per 1000) and Western Europe the lowest (11 per 1000). Abortion rates are lower overall in areas where abortion is generally restricted by law (and where many abortions are performed under unsafe conditions) than in areas where abortion is legally permitted (Henshaw et al. 1999). Where abortion is restricted by law, there is another concern. Children born from unwanted pregnancies, after abortion has been refused, have much less favourable life outcomes. In the Prague Study of Subjects born of Unwanted Pregnancies, Kubička et al. (1995) showed at age 30, the unwanted children had significantly poorer outcomes compared to children from wanted pregnancies.

Has women’s employment influenced fertility behaviour?

A key feature in declining fertility is the increased range of choices parents have, and the choices they perceive that their children should have. Central to these is income and employment.

In most societies, a man’s higher income and social status is related to also having more children (Nettle and Pollet 2008). This is especially because men with low education and income are more likely to remain childless. By contrast, highly educated women often remain without children. It would be a mistake, however, to divide women everywhere into career-oriented women with few or no children and family-centred women with many children. Rather, most women opt for both interesting employment and children – given the choice. As a result, although there is an uncertain relationship between employment and low fertility in the developing world, the association is more certain in OECD countries.

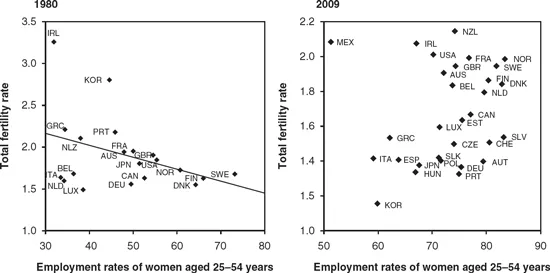

As can be seen in Figure 1.2, there is a fairly strong relationship between female employment rates and TFRs, and this has switched from negative to positive in just three decades. Today, societies with a high level of female employment, and usually also a longer history of full-time working women, have had to adapt to dual earner families and have higher fertility rates (McDonald 2006). In the Scandinavian countries with high gender equality, mothers have fairly equal numbers of children across all educational groups (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008). By contrast, societies where women have entered the labour market, without a corresponding change in family values and family policies, witness the sharpest reductions in childbearing. Particularly dramatic is the situation in Korea and the changes between 1980 and 2009.

Figure 1.2 Cross-country relation between female employment rates and total fertility rates, 1980 and 2009

Source: Permission to reproduce from ‘Employment rates – OECD Employment Outlook’, UN World Statistics Pocketbook, 2010, and ‘Fertility rates – National statistical authorities, UN Statistical Division and Eurostat Demographic Statistics, 2010’ (OECD 2010b).

Economic opportunities are also related to the timing of the first child. The transition to parenthood is happening increasingly late in most countries, especially among those with higher education (Billari et al. 2006). Having children later in life has usually been seen as contributing to lower fertility. However, in many highly develop...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: What Is Happening to Fertility Behaviour?

- Part II: What Are the Reasons for Women Having Fewer Children?

- Part III: What Will Be the Impact of Women Having Fewer Babies?

- Part IV: A Look into the Crystal Ball: Possible Responses

- Index