- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

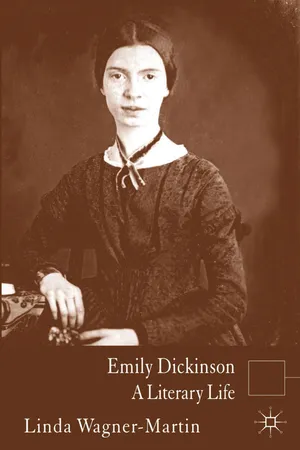

With special attention to Emily Dickinson's growth into a poet, this literary biographical study charts Dickinson's hard-won brilliance as she worked, largely alone, to become the unique American woman writer of the nineteenth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Emily Dickinson by L. Wagner-Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism in Poetry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Reaching 1850

In the spring of 1850, Amherst, Massachusetts was a thriving if comparatively isolated town of 4000. When the three Dickinson children (Figure 1.1) were growing up there, the village was still reached from nearby communities only by stage which traveled the roads and under the covered bridges from Hadley. A resident of Springfield could have come the 18 miles by train to Northampton; then the stage would take over. Finally, in 1853, the Amherst-Belchertown Railway was completed (Ward Emily Dickinson’s Letters 31). For all the difficulties of travel, however, the Edward Dickinsons were considered a family that did travel. It was the mark of their prestigious position in the traditional—and traditionally classed—town. Their journeys took them to the eastern coast, to Boston and Philadelphia and, occasionally, to Washington, DC. If they went abroad, which was unlikely, they traveled to England, France, and perhaps Italy: these were the countries they read about in the elite books of the English-speaking world. In effect, such patterns of travel reflected their intellectual interest: the white and educated New Englanders kept themselves surrounded by other white people. While some Amherst families employed African American household help, most residents who hired cooks, laundresses, and yard workers drew from the newly-arrived Irish population (Murray 3, 10).

In the spring of 1850, Emily Dickinson was approaching 20. William (usually called Austin) was already 22, a student at Amherst College; and Lavinia (Vinnie) was 17. Emily had already completed her studies at Amherst Academy, and had gone for most of a year to the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. Sometimes her attendance was sporadic because Emily was considered fragile. In a century when deaths from tuberculosis decimated the population (deaths occurred among teenagers as readily as among parents), people who appeared to be frail, or who developed serious coughs with colds, were sheltered (Mamunes 3–4). It is thought that 22 percent of deaths in Massachusetts during the mid-nineteenth century came from tuberculosis (Habegger 640–1).

Figure 1.1 O.A. Bullard’s painting of the three Dickinson children (Dickinson Room. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

In 1850 Emily was a proud, talented, and (at times) self-satisfied young woman on the edge of adulthood, a woman trained into the dimity convictions of the so-called separate spheres of the nineteenth century. Upper-class women were protected from the hard work that many lower-class women were forced to undertake. Living in the comfort of their fathers’ homes (at least until their marriages to equally well placed suitors), these middle- and upper-class women helped with household tasks, had social lives with other similarly educated young people, and saw the way religious beliefs persuaded good young adults to behave (Kelley Ch 1). While not luxurious, this life of social propriety was coercive. Once Emily had finished her formal education, she realized how codified women’s social roles were. As she wrote to Abiah Root, her former classmate from Amherst Academy, “I expect you have a great many prim, starched up young ladies there, who, I doubt not, are perfect models of propriety and good behavior. If they are, don’t let your free spirit be chained by them” (LI 13).

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson from early on in her childhood considered herself a free spirit. She also seemed to grasp the role of observer, the role of Other. In the words of Charlotte Nekola, one of the issues in high relief during the mid-nineteenth century was “how to claim self within an ideology of self-denial . . . womanhood was defined as absence of self” (Nekola 148). Emily Dickinson recognized this inherent conflict: being female “hindered rather than fostered the development of ego, voice, and imagination” or, in other words, within the cult of true womanhood, the female imagination was, at times, equated with selfishness (Nekola 149). As a result, Emily looked on at accepted social behaviors—and she often participated in them during her late teens—but she also came to see herself as her father’s daughter and Austin’s sister: one of a family triumvirate of witty intellectuals. In that role, Emily became almost genderless.

Whether because of her own talents—among them her across-the-board academic competence—or because her parents had already tried to erase the parameters of gender difference for her, Emily felt as if she were Austin’s equal. As her letters to him show, once he is away in college and then teaching school, she cajoles, jokes, and exaggerates with the perfect understanding that Austin loves her, as does her father, without making judgments. In the hierarchy of family power, Emily had early on become Edward’s second son; it might well be said that she was his favorite son.

To identify as Emily did with men, and with the privileges of a man’s education, was often a means of emphasizing the life of the mind rather than that of housekeeping. Judging from the periodicals and newspapers to which the Dickinsons subscribed, homelife was itself an intellectual pursuit. Amherst residents received two mail deliveries a day. The Dickinsons took three Northern newspapers as well as Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Scribner’s Monthly, and—from its founding in 1857—Atlantic Monthly (Stewart 322). In the words of one historian, “the Atlantic was not a channel for American literature—it was American literature” (Pollitt 167). Staying abreast of national and state news, as well as literary, scientific, and humanistic interests, was easy; it was also expected. But while the “men” of the family were reading the latest journals and papers, the routine housekeeping tasks were also ongoing. Much as she tried to avoid them, Emily still felt the conflict: should she be reading or should she be washing dishes? With what seems to be near derision, Emily jokes about her mother’s obsession with those perpetual household duties. She writes about the reason she could not send along her mother’s good wishes: “Mother would send her love—but she is in the ‘eave spout,’ sweeping up a leaf, that blew in, last November” (Habegger 63). As Dickinson’s recent biographer Alfred Habegger describes this extended joke, pointing out that the letter was probably written in August, long after the leaf got lodged in the roof gutter’s spout, he terms Emily’s drawing “an unforgettable picture of an obsessed New England housekeeper driven from the comforts of home and much too busy to send her love, let alone to write” (Habegger 64).

Critics often commented on the fact that the “quiet and self-effacing” Emily Norcross, the woman Edward Dickinson had chosen to be his bride, was “excellent at managing her household” (Longsworth Amherst 22). She was responsibly educated and from a relatively affluent family in Munson. Yet as their correspondence from the several years of their engagement suggests, Emily was not a reader. She also seemed unwilling to write, or wrote with a practicality that expressed little romance: she was not a reader/writer as her daughter Emily Elizabeth would come to be, or was instinctively. Even as Barbara Mossberg contends that Dickinson’s relationship with her mother was much less distant than some critics have suggested (Mossberg 38), there are few references in Dickinson’s early letters that show any pride in either her mother or her role within the family. It does seem clear that the Norcross family, and perhaps eventually the Dickinson family in Amherst, professed the doctrines of the Popular Health Movement of the 1820s and the 1830s. Women understood that doing their own chores and cleaning—as well as gardening—could satisfy their physical need for exercise, and there are mentions—sometimes urgent—of the need for both Emily and Vinnie to get outdoors (Ehrenreich and English 69–70).

Longsworth also speculates that Emily Norcross may have inherited her “fearful, anxious temperament” from her own mother, Betsey Fay Norcross (Longsworth Amherst 22). Emily Norcross seemed to take immense pride in doing the housework and running the Dickinson house impeccably. As Habegger (62) points out, however, her life was marked by “her drivenness, her extreme thrift.” To illustrate these characteristics, he tells the story of Emily’s accepting boarders (boys who were attending Amherst College and preferred staying with a reputable family), just a few months before her first child was due. The boys, a son and a nephew of a leading Springfield attorney, may have been seen as giving Edward Dickinson some sort of political advantage. But acknowledging the fact that throughout the Dickinsons’ early years of marriage, the Norcross family worried about Emily—urging her to return home for rests, sending her girls from their family to help out—her decision to invite the boys to board seems foolhardy.

The truth about the Dickinson family was that poverty haunted their lives. Whereas critics have emphasized the fact that Emily Norcross insisted on being, literally, the maid of all work, seeing the family’s financial situation whole excuses at least some of her obsessiveness. After Edward Dickinson had proposed to her and she had eventually accepted, he deferred their marriage for several years while he tried to pay off debts his father, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, had accumulated. Samuel was one of the founders of Amherst Academy; he was continuously in financial difficulties, although he wanted to be seen as one of Amherst’s leading citizens. As he poured what resources he had into Amherst Academy and Amherst College, his children knew they would need to help with this task—and with his other projects. Finally a bankrupt, Samuel “left Amherst in disgrace” (Murray 65) and moved to northern Ohio for a position; he died there, miles from his family, and left a legacy of possible chicanery as well as bankruptcy. Eventually in 1825 the family had to sell the Homestead, which Samuel had built in 1813, and which they then rented a part of during their early married years (Longsworth Amherst 15, Murray 65).

lt also seems clear, because the Dickinsons never had a full-time maid (according to the 1850 federal census 7 records), that all the children helped with the housework, the laundry, the tailoring, the cooking, and the yard. Aife Murray (66) tells the story that Emily was to be apprenticed to a baker when she was 14; such a plan seems at odds with the fact that all three of the Dickinson children had the best possible educations, Emily and Vinnie as well as Austin. As Murray notes, Emily was “already accomplished in knitting . . . needlework and mending.” She went to school and had piano lessons, had many indoor plants, and “privately arranged German lessons” (Murray 66). It was not until March 7, 1850 that Edward Dickinson ran an ad for “a girl or woman to do the entire work of a small family” (Murray 73). Meanwhile, in the 1850 census, Emily Dickinson had listed her occupation as “keeping house,” and then in a later letter complains when Vinnie is away, “my two hands but two—not four or five as they ought to be, and so many wants—and me so very handy—and my time of so little account—and my writing so very needless” (LI 82).

Alfred Habegger also traces the anxiety stemming from financial losses from early in the family’s history: putting off their wedding for several years, trying to maintain a house (or at least part of a house) with so little help, and infecting their children with their own financial worries. He believes that Emily especially felt “her parents’ anxiety about financial insolvency” (Habegger 57). It is probable that this financial worry helped to shape Emily’s choice of studies at both Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke. She turned again and again to scientific curricula. In college, she took “ancient history and rhetoric” as well as “all science courses: algebra, Euclid [geometry], physiology, chemistry and astronomy” (Gordon 42). The authority on the way Emily Dickinson both studied science and drew from it for her poetry is Robin Peel, whose 2010 book thoroughly discusses both the courses (and their texts and emphases) and relevant Dickinson poems. Peel’s aim is to present Emily as a “scientific investigator,” drawing on what she sees as the exciting new, scientific culture (Peel 13–14). He asks that readers see Emily Dickinson “as a concealed natural philosopher/scientist” working in ways that mimic scientists contemporary with her (14). (One thinks of Emily’s trip home from college in 1848 for the dedication of the telescope in the Amherst Observatory, installed as part of the Octagon Building, an excitement the whole town shared. The various segments of The Smithsonian Institute and Museum in Washington, DC, were not in place until a decade later, 1859, Peel 21).

The connection between Emily’s consistent interest in science and her family’s often precarious finances may be that she saw some opportunities for employment in the newly categorized field: Peel notes that some of her structures in her early poems were geared to making “scientific claims” and emphasizing scientific details; in fact, it could be that her creation of the fascicles (the small tied-together booklets of her poems) was a way of preserving field notes (Peel 17). To undergird this interest was the obvious fact that many of the journals carried essays about matters that were more scientific than philosophical: family discussion would have privileged “science” almost unconsciously.

Peel points out that the fascination with the new that marked the 1830s and 1840s changed during the later years of Emily’s education. Rather than just describing and observing, people interested in science were now applying the principles, especially in medical fields. Creating hypotheses became the standard for proving material learned, rather than memorizing the long blocks of information that had previously marked science class methodology (Peel 78, 17). He notes how seriously Emily took her herbarium, and how often in her poetry she closely observed “flowers, insects, and birds . . . as if she were making a scientific record” (91, 172). Throughout her poems, Dickinson uses the metaphor of sight, as in “I see New Englandly” (Peel 81). There are also more volcanoes, winds, and storms in her poems than might be expected.

All the courses of study at Amherst Academy were more scientific than most curricula because the third president of the school was Edward Hitchcock, a well-known geologist with strong interests in paleontology. While Emily often followed the classes that Austin had chosen, Vinnie seemed to prefer a more humanities-based course of study. Again, Emily was no doubt aligning herself with Austin as a way of interesting her father in her intellectual prowess.

With the sometimes strange juxtapositions that occur in any culture, the impetus to study science came at a time when Massachusetts was overtaken with protestant revivalism. The coercion to accept Christ, to become a Christian and an active church member, was almost frenetic at mid-century. Cynthia Griffin Wolff acknowledges that despite Emily Dickinson’s comparatively wide knowledge of science and philosophy, all her educable life she struggled with the question of conversion (Wolff 87): “Even by the middle of the nineteenth century, Amherst—both college and town—still looked upon conversion as one of the crucial events that marked the division between carefree youth and responsible adulthood . . . . [conversion] was a recognized public rite of passage” (Wolff 93).

Emily Norcross had converted in 1831, but no other family members had done so. It was, however, the revival meetings in the winter and spring of 1850 that succeeded in proselytizing much of Amherst. On August 11, 1850, Emily’s father converted; in November, Vinnie professed her faith (Wolff 104). Emily maintained the position that had grown during her months attending Mount Holyoke: she was a non-believer.

The Mount Holyoke experience was unexpectedly coercive. Mary Lyon, the head of the college and a protégé of Edward Hitchcock, created an atmosphere at the school that was “unremitting and inescapable.” Women were recognized at assemblies on their standing as converts or non-converts; Emily Dickinson was grouped in the “No hope” category and saw many of her peers in that classification weeping because they were not saved (Wolff 100–1). (Habegger speaks about the non-believers having to attend what he calls the “painful collective inquiry sessions,” 199). In one instance, at the deathbed of a beautiful classmate [Emma Washburn], the unconverted students were asked to come so that Emma might urge their conversions. Her death in itself (occurring from “galloping” consumption) was a scarifying event, but to have her implore her friends to follow her to God was unforgettable (Mamunes 45–6). Emily Dickinson felt even more of an outsider during this revival turmoil, especially when several of her best friends converted later in 1850.

It is also true that much of Emily Dickinson’s education came from the people she knew and loved—either in person or through her many letters. It is impossible, then, to replicate what she had learned at the close of her formal education by simply studying the textbooks from her classes, at either Amherst Academy or Mount Holyoke. For more than two years, Ben Newton, one of her father’s law clerks/students, had been Emily’s tutor. She called him that a decade later—after his death—as she wrote about him and his tutelage to friends, and it seems clear that from the time she left Mount Holyoke at her father’s insistence, worried as he often was about her timorous health, until Newton moved from Amherst back to Worcester, the two spent great amounts of time together. Newton was an open-minded man, not yet committed to Christ, interested in new writers like the Brontës and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and encouraging about Emily’s poetry. He told her she would one day be a poet. From a poor farm family, Newton had not attended college but he was apt, smart, and dedicated to becoming a lawyer. He was also ill with consumption, the primary malady of the mid-nineteenth century in Amherst and its surroundings. At 26, Newton had already spent years earning the money for his law study—probably working as a teacher—but he remained terrifically poor: biographers have long wondered how he paid for his two years in Amherst, and the following year in Worcester, after which he finally earned his degree (Mamunes 14–15). Emily was only 17 but she was well-educated, intent on becoming what she could be even though resistant to conversion, appreciative of the beauties of nature—as was Newton—and deeply worried about her own illnesses (which seem at this time to be connected with consumption although somewhat later, Lyndall Gordon suggests, she may have developed fainting and seizure disorders as well). (Gordon 78–135).

Rife with novels, stories and poems about the sad lives of consumptives, mid-nineteenth century American culture provided examp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Note on Conventions

- 1 Reaching 1850

- 2 Dickinson’s Search, to Find the Poem of Her Being

- 3 Losses into Art

- 4 Dickinson’s Expanding Readership

- 5 Dickinson and War

- 6 Colonel Higginson as Mentor

- 7 Life Without Home, For the Last Time

- 8 Dickinson’s Fascicles, Beginnings and Endings

- 9 The Painful Interim

- 10 To Define “Belief”

- 11 1865, The Late Miracle

- 12 Maintaining Urgency

- 13 Colonel Higginson, Appearing

- 14 1870–1873

- 15 The Beginning of the Calendar of Deaths

- 16 Surviving Death

- 17 “Mother’s Hopeless Illness”

- 18 Courtships

- 19 “The Poets Light but Lamps”

- 20 The Loving Dickinson

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index