eBook - ePub

Ruling, Resources and Religion in China

Managing the Multiethnic State in the 21st Century

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ruling, Resources and Religion in China

Managing the Multiethnic State in the 21st Century

About this book

China is growing in importance to the economies and governments of the world, and it has been run by men with very different ideas. How China copes with the pressures for good governance with the Asian economic model, treats its ethnic minorities under scrutiny, and gathers resources to fuel its dynamic economy, impacts us all.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ruling, Resources and Religion in China by Kenneth A. Loparo,Elizabeth Van Wie Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Ruling and Governance

A dump truck rammed into 70 border patrol paramilitary police during a routine early morning jog, in just one instance that indicates the complications surrounding governance in multiethnic China. Hitting an electrical pole, two Uyghur men jumped out, tossed homemade explosives and attacked surrounding police with knives. Fourteen officers died on the spot, two others on the way to the hospital.1 Can strife like this mean that ruling and governance has failed in a large, multiethnic country?2

Most of China’s governance challenges, however, are not new to observers, but have been exhibited in other East Asian countries, which post-Deng Xiaoping leaders have watched closely. There are some notable governance challenge results that the Chinese Communist Party (the Party) would like to avoid. One result is that the authoritarian governing systems that developed the original East Asian model fell in South Korea and Taiwan as the twentieth century closed. While the original East Asian model assumed initial economic growth and then the emergence of a multiparty system, as did happen in South Korea and Taiwan, new Asian models that remained quasi-single party developed. China would much rather pattern itself on the systems in Japan and Singapore that have to a greater or lesser extent managed to hold on to one-party rule. Another challenge response is that China is so diverse in terms of ethnicities, geography, development level and heritage that the models of much smaller, more homogeneous East Asian model neighbors—Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea3—hardly apply. Overall, the model’s general economic approach appears to be sound,4 but what is less certain is the connection between good governance and economic development.

Major governance challenges in China occur in various issue areas and merit a variety of potential solutions, including: (1) areas targeted by elections and intraparty democracy, especially social tensions, partly due to increasing inequality within society and partly linked to corruption;5 (2) a comprehensive program of far-reaching institutional reforms to define the role of the state, improve management of public spending, make public action more efficient and effective, and assure social stability;6 (3) and pacification of occasional violence by ethnic minorities that sometimes challenges attempts of good governance.

Political reform

Good governance is a generic term originally borrowed from corporate governance, but has come to have a much wider, more diverse meaning when applied to political governance. Political governance tends to look at issues like the civil and political rights of freedom of press and speech; elections; social and economic rights including poverty, infant mortality, life expectancy, literacy and government spending on education, health and military; law and order and social stability; minority rights and women’s rights; and the quality of governance: rule of law, corruption, and regulatory effectiveness and quality.7

As a major subtext, good governance has come to replace the rhetoric of democracy of earlier decades. The East Asian model offers several examples of governance: the decades-long domination of politics by the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, wealth with a hybrid authoritarian/democratic regime in Singapore,8 the breakaway parties of both the Kuomintang and Democratic People’s Party forming into dual pan-coalitions in Taiwan, and the dynamic multiparty system of South Korea.

China’s leaders are mentioning democracy with increasing frequency and detail in this current environment where good governance is so often linked with the term, with the intention of implementing political reform that enhances rather than undermines the governance of the Party.9 When Hu Jintao was head of the Central Party School, a position later held by Xi Jinping, this school for training senior Party cadres studied sensitive topics such as political reform, direct elections and Europe’s social-democratic parties.10 Then in 2002, as he assumed the presidency, Hu Jintao said that one of his major reform tasks as president was to “strengthen democracy at all levels.”11 Again in a presidential 2004 speech to the Australian Parliament, and repeatedly during his 2006 visit to the United States, Hu Jintao mentioned democracy: “Democracy is the common pursuit of mankind, and all countries must earnestly protect the democratic rights of the people.”12 Then in his 2007 speech to the 17th National People’s Congress, Hu said: “To develop socialist democracy is our long-term goal. The government should expand political participation channels for ordinary people, enrich the forms of participation and promote a scientific and democratic decision-making process.”13

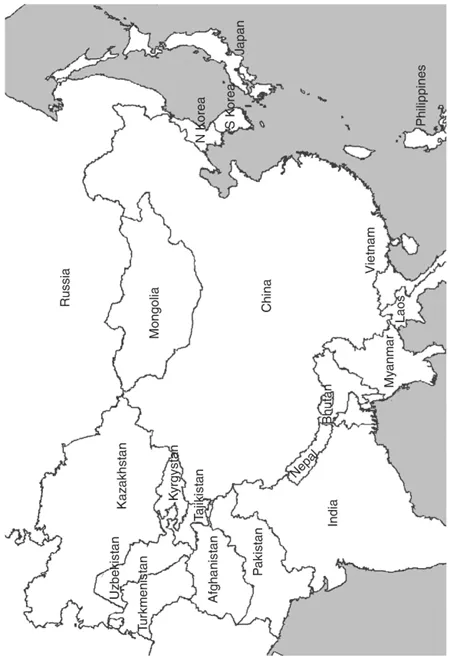

Map 1.1 China in Asia

Wen Jiabao, like Hu Jintao, articulated the main Chinese vision of democracy, which requires the preservation of the Party’s leadership, although with a “deliberative” form of politics that allows individual citizens and groups to add their views to the decision-making process, rather than an open, multiparty competition for national power. In his address to the 2007 National People’s Congress, as Premier, Wen Jiabao declared: “Developing democracy and improving the legal system are basic requirements of the socialist system.”14 According to John L. Thornton, Wen Jiabao was asked what he meant by democracy, what form democracy was likely to take in China, and over what time frame. “When we talk about democracy,” Wen responded, “we usually refer to three key components: elections, judicial independence, and supervision based on checks and balances.” Apparently, Wen Jiabao envisioned elections expanding gradually from villages to towns, counties, and even provinces as well as judicial reform to assure the judiciary’s “dignity, justice, and independence.” Wen Jiabao assured the questioners that “We have to move toward democracy. We have many problems, but we know the direction in which we are going.”15 There is no reason to believe that democracy with “Chinese characteristics” will be abandoned for Western democracy any time soon.16

There is a dual track to advance the democratization process within governance being experimented with in Beijing: one track from the top down is intraparty democracy that then spills over into the state politics, and the other track is from the bottom up with grassroots elections that then rise to provincial- and national-level political institutions. Elections are being closely watched in international circles.17 In a pattern redolent of how China approached market reforms in the 1980s, Beijing now encourages limited governance experimentation at the local level, closely watching the election experiments. As different localities try different things, a senior official at the Central Party School told John L. Thornton, the Central Party School studies the results.18

In the parlance of good governance, however, elections themselves are not sufficient, but rather the terms “free and fair” are almost always attached. According to Julia Kwong, the electorate still holds some traditional values that may stand in the way of making choices appropriate to fair and free elections.19 One concern is corruption, because personal ties, which contribute to corruption, traditionally play an important role in Chinese social life, as elsewhere in Asia, and continue to be a strong consideration in elections. However, China’s tradition of institutionalized rules makes corruption less prevalent than in other developing countries.

Another pressing concern regarding elections is the perception of the election relationship, in which Chinese citizens largely see themselves as submissive subjects looking to officials to protect and safeguard their interests as opposed to the concept that the electorate rules. Nonetheless, suffrage is nearly universal—almost every law-abiding citizen living in the area of his or her household registration has the right to vote.20 Elections are shaped by subtle, but powerful, cultural and social forces, which political leaders have to identify and adopt the appropriate strategies for developing sustainable institutions.21

A third concern, and probably the most prevalent, is official manipulation surrounding elections. Eligible voters are permitted to nominate candidates, the number of candidates is more than the offices available, and voters use secret ballots.22 There is election political machinery, and elections are not subject to military intimidation. However, Chinese political leaders, despite the change in rules in 1982, continue to influence the elections in order to maintain their power and protect their interests, including the prerogative to select the final slate of candidates on the ballot sheet, put the names of their favored candidates ahead of others on the ballot, and provide their candidates with large resources.23

The dual tracks of intraparty democracy and experiments with elections are designed to prolong and enhance Party rule.24 Intraparty democracy is currently considered by Party leaders to be more significant for China’s long-term political reform than the experiments in local elections. A Party that accepts open debate, internal leadership elections and decision-making by a diverse leadership group with disparate power centers, according to twenty-first century leadership thinking, is a prerequisite for good governance in the country as a whole. Hu and Wen, as president and premier, routinely called for more discussion, consultation and group decision-making within the Party. Intraparty democracy was a centerpiece of Hu Jintao’s keynote address to the 17th Party Congress in September 2007. Not long after the meeting, Li Yuanchao, as head of the Party Organization Department, published a 7,000-character essay in the People’s Daily elaborating on Hu’s call for intraparty democracy.25

One of the ways the Party promotes intraparty democracy is by the Party’s system of managing the selection of leaders, putting forward multiple candidates for positions. The cadre management system and the cadre responsibility system assess the capacity of the Party and allow it to shift its policy priority.26

Another way that the Party promotes intraparty democracy is through “coalitions”—organized “factions” are still not acknowledged. This leads to predictions that the Party may one day resemble Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, where formal, organized coalitions compete for senior political slots and advocate different policy positions.27 The existence of political poles was present in modern China as far as back as Mao Zedong with the Reds/Maoists (leftists) versus Experts/Pragmatists (rightists) coalitions. Several groups are apparent. One interest group is the Shanghai clique, sometimes referred to as former-President Jiang Zemin’s coalition, which is squarely in the midst of the right camp. The right largely supports slow political reforms and rapid economic development. Another group, the “new right,” pushes the Party leadership for faster political reform, warning that a lack of progress could lead to social unrest and political crises.28 The left, with their ideological roots in Maoism, accuse the leadership of embracing a breed of capitalism that has spawned a dangerous mix of rampant corruption, unemployment, a widening income gap and potential social unrest, warning that the socialist cause has lost its direction and that the country is “going down an evil road.”29 Another group, the “new left,” criticizes China’s economic reform, but with less ideological roots in Maoism and is comprised of some army officers, old communist Long Marchers, and leftist leaning intellectuals. It is this latter group of intellectuals who are most frightening because they are youngish professors in their forties and fifties at primarily Beijing universities with American PhDs. They are ardently anti-United States (arguing that from their years in the US, they understand the United States best), believe that not only is conflict inevitable but also an early conflict is in China’s best interest, are strongly anti-democratic and dislike the central government’s foreign policy. Hu Jintao and his alumni-based coalition of the Central Party School sought a middle ground. The Central Party School is a tool for the Party to shift the information given to new cadres.30

The debate between the right and left focuses on a multitude of social ills, including corruption and widespread social injustices, to push their agendas and pressure the Chinese leadership. In universities, think tanks, journals, the Internet and Party forums debate flows about the direction of the country: economists debate inequality; political theorists argue about the relative importance of elections and the rule of law; and policy conservatives argue with liberal internationalists about grand strategy in foreign affairs.31 Academics and thinkers often speak freely about political reform. The Chinese like to argue whether it is the intellectuals that influence politicians, or whether groups of politicians use pet intellectuals as informal mouthpieces to advance their own views. Either way, these debates have become part of the political process. Intellectuals are, for example, regularly asked to brief the politburo in study sessions; they prepare reports that feed into the Party’s five-year plans; and they advise on the government’s white papers.32

Partly in response to mounting pressure from the right and left, Hu subtly refined his policies in a bid to win broader support.33 Partly to avoid the pitfalls of extremes, Hu Jintao seems comfortable in the middle, as technocrats often do.34 To reach the middle, a shift toward the left, compared to the preceding Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji administration, occurred under the Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao leadership, but not...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Ruling and Governance

- 2 Leadership and Resources

- 3 Regional Challenges for Resources and Religion

- 4 Tibet Question

- 5 Uyghur Question

- 6 Ruling, Resources and Religion

- 7 Outcomes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index