- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

(Post)apartheid Conditions: Psychoanalysis and Social Formation advances a series of psychoanalytic perspectives on contemporary South Africa, exploring key psychosocial topics such as space-identity, social fantasy, the body, whiteness, memory and nostalgia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access (Post)apartheid Conditions by D. Hook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Personality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Monumental Uncanny

Given the aim within psychosocial studies of utilizing concepts that exist ‘indivisibly between’ the psychical and the social, it is fitting that this first chapter tackles the topic of psychical space and its relation to ideology. I have opted to start with a psychosocial ‘case study’ of an apartheid monument, for another reason also: much of the empirical material gathered here is squarely located in the post-apartheid context. Although each of the chapters in this book straddle the apartheid/post-apartheid divide in some or other way, this chapter looks further back than any other into apartheid history.

South Africa’s system of apartheid, like that of many other oppressive (neo)colonial regimes of power, relied upon intimidating forms of spatiality as part of its attempt to align its subjects to its chosen ideology. One might take as exemplary in this respect the ‘spectral influence’ of monumental sites which played a key role in interpellating such subjects, in the ‘spatial subjectivization’ of its citizens. This then is the question of this chapter: if monumental spaces may be said to possess such a subliminal – even unconscious – ideological force, then how might we go about conceptualizing this particularly colonial mode of spatial subjectivization in which space recapitulates discourse, incarnating certain ‘essences’, particular relations of privileges in the process? The answer I will go on to pose, which links psychoanalytic theorizations of uncanny embodiment to unconscious ideological belief, offers a novel means of thinking the irrational powers of space.

Strijdom Square

On Tuesday 15 November 1988, in a self-declared attempt to start the third ‘Boer war’, 23-year old right-wing extremist Barend Strydom entered Strijdom Square (named after his unrelated namesake, J.G. Strijdom, former apartheid prime minister), and began a premeditated killing spree. At the same time that President P.W. Botha was expected to announce Nelson Mandela’s release, and while the visiting Mother Teresa prayed for peace at the Pretoria showgrounds, Strydom began firing upon unsuspecting black men and women in Pretoria’s busiest public square. Strydom had carefully picked the site of event such that it would amplify his actions, and incite a resurgence of the powerful racial division of South Africa that he believed was under threat.1 A letter found after the crimes, addressed to his father, noted ‘What I am about to do is not a punishment for you. It serves as the first shots in the Third Freedom war which is already being waged’ (cited in Rosen, 1992, p. 2).

Strijdom Square is situated in the centre of what had been apartheid’s capital city – Pretoria. It constituted a whole city block devoted to Afrikaner heritage, accomplishment and culture. Rosen (1992), for one, reads it as a monumental public space that aimed to build and mould an Afrikaner National identity, a space where ‘planning, construction and meaning ... all project and celebrate a homogenous, single public identity’ (p. 4). The Square was named after Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom, a man renowned for his visions of South Africa’s republican ‘freedom’ and racial segregation. Built on the site of what had been, until the 1960s, the heart of a thriving Indian market, which was cleared by forced removals and then demolished, Strijdom Square epitomized, even in its basic conditions of possibility, the principles of racial superiority through the power of repressive physical force.

The Square served as home to the head office of South Africa’s largest Afrikaans-owned bank – Volkskas (‘Nation’s chest’), founded with exclusively Afrikaner capital, with the express aim of protecting Afrikaner assets. The architecturally-celebrated Volkskas building was, at 132 metres, the highest building in the city, described at the time by its funders as ‘an Afrikaner monument that reaches into the heavens with the other high buildings of the 20th Century’ (Bruinette and van Vuuren, 1977). The domicile of the State Theatre and Opera, the Square was a rallying-point for the white and Afrikaner elite, an attempt to emulate the high culture of similar European institutions.

Like much else within the square, the Volkskas building was built exclusively from materials indigenous to the country, such that the content of this architectural statement of Afrikaner nationalism and independence would embody the land to which its people were thought to have sole prerogative. A concern with indigenous materials was similarly visible in the gardens of the Square: four separated tracts of flora, each embodying the characteristic plant-life of the country’s then four provinces. These provinces were themselves monumentally symbolized in an iconic statue of four powerful horses, meaning to connote the national unity of joint provincial strength. The signature image for many of Strijdom Square however was the gargantuan and disembodied head of the former apartheid statesman. According to the commemorative programme distributed at the unveiling of the statue, the act of reducing the figure of Strijdom to a head, meant only the essential qualities of the leader remained. In the programme it is also noted that the 12-foot high head is placed on a level close to the spectator so that every spectator can stand literally below his gaze and metaphorically come under his influence. For many the monument functioned as the unambiguous and material declaration of Strijdom’s determination that ‘if the white man cannot be ruler he loses his identity’ (Diphane, cited in Rosen, 1992, p. 4).

Illustration 1.1 The main components of the sculptural programme of Strijdom Square: ‘floating’ bust of Strijdom with protective dome, and monumental charging horses, emblems of ‘joint provincial strength’, which likewise appear to hover, held aloft by the waters of one of the Square’s water-features (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

Illustration 1.2 The 132 metre high Volkskas building which provides the backdrop for the Strijdom Monument (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

Illustration 1.3 Panoramic view of Strijdom Square with State Theatre (to the left), Volkskas building (centre) and informal traders (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

Illustration 1.4 Strijdom Square at night; Strijdom’s head illuminated (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

Illustration 1.5 Still-frame from video shot showing the relative proportions of the Strijdom Head and onlooker (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

An ominous and foreboding monument, the floating head appeared as a concretization of the unbending authority of apartheid’s power, the unquestionable presence and ‘rights’ of its supremacy, an emblem of the warrants of surveillance and control that were its alone to operate. More than a salute to power however, or a naturalization of racial-cultural superiority, the head was, to many, an embodiment (or more literally, a disembodiment) of political intimidation. Unchallengeable, unchanging – not to mention disproportionately massive – the head made for a positively foreboding icon, a ‘monument of threat’, a warning against the consequences of disobedience to the apartheid regime. The disembodied head itself seemed somehow indicative of the violence so intrinsic to this political order, an unconscious connation of the brutal physical outcomes that would necessary follow any challenge to the sovereignty of the apartheid state.

An assemblage of economic power, idealized cultural values, indexical natural elements, austere monument and marker of oppressive physical force, Strijdom Square both epitomized the values of republican Afrikaner nationalism, and presented an implicit threat to those who would challenge it. There could, in short, hardly be a more ideologically appropriate site from which Barend Strydom could begin his killing spree.

On 29 September 1992, the day Strydom was released from prison on the basis of political amnesty, a large amount of red dye was poured into the fountain on the Square: an act that seemed to iconoclastically subvert the cultural and ideological meaning of the Square, inverting its vision of Afrikaner freedom into a potent reminder of whose freedoms it had excluded.2 The disturbing effects of this act were reported by the Pretoria News with the lead-in ‘Strange symbolism’; its report made mention of the political ambiguity of the event:

the water in the Strijdom Square fountain ran red today. Who put the dye into the water is unknown. Was it right-wingers reminding people of the atrocities committed on the square ... or friends and relatives of the victims of the infamous shooting spree? (p. 1)

In total, Barend Strydom killed eight and wounded 14 black men and women in his vicious rampage, an act he ‘legitimized’ in his bid for amnesty as an act of war to protect the Afrikaner nation.

‘Spatio-discursive’ subjectivity and monumentality

The disturbing history of Strijdom Square presents us with a monumental site of real and symbolic violence, where identity, power and space intersected in uncanny ways. It poses for us the distinctively psychosocial challenge of understanding the complex relationship between these factors. How then are we to account for the powerful bonds of identification underwriting the ideological potency of particular places?

Illustration 1.6 Close-up photograph image depicting the features of the Strijdom head (Image courtesy Michele Vrdoljak)

The notion that space – or more specifically, delimited sites of invested social and cultural meaning, that is, place – plays a vital role in informing practices of power and identity is not a new idea within social theory. Soja’s (1989) notion of spatiality is perhaps the foremost example here, although, in differing ways, Fanon’s conceptualization of the ‘Manichean divisions of colonial space’, Bourdieu’s (1977) idea of the habitus, and Foucault’s (1997) notion of heterotopia, all interestingly lend themselves to further explorations of the intersections of power, identity and monumental space. Psychoanalysis presents itself as an obvious ally here, especially given the affective, bodily and fantasmatic qualities characteristic of monumental space. Aligned to this consideration is the fact that psychoanalysis is, arguably, far better equipped than much sociological discourse theory when it comes to theorizing relations of psychical identification.

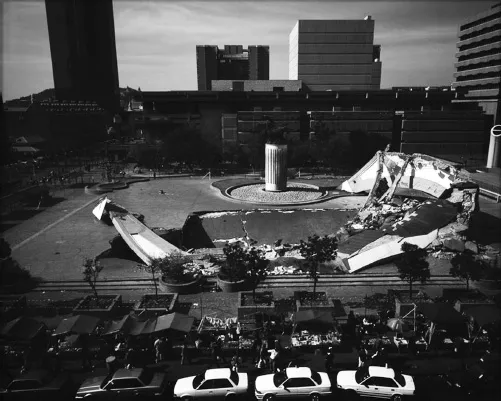

Illustration 1.7 Strijdom Square, 31 May 2001, hours after the collapse of the Strijdom Head and dome, on the anniversary of apartheid South Africa’s ‘Republic Day’ (Image courtesy Abri Fourie)

Integral to discursive approaches to the space–power–identity relation is the assumption, via Soja’s (1989) concept of spatiality, that space exists in socially constructed and practised forms intricately intertwined with socio-political relations of power, meaning and ideology. Soja (1989) argues that the organization, meaning and functioning of space is a product of social translation, transformation and experience. He quotes Lefebvre:

Space is not … removed from ideology and politics; it has always been political and strategic ... Space has been shaped and moulded from historical and natural elements, but this has always been a political process. Space is political and ideological. It is literally filled with ideologies. (Lefebvre, cited in Soja, 1989, p. 80)

Similarly prioritizing the domain of ‘spatiality’, Dixon and Durrheim (2000) offer the notion of a ‘grounds of identity’, so as to emphasize the ways in which physical (and socio-discursive) space operates as a resource of identity. Created through talk, a ‘grounds of identity’ is ‘a social construction that allows subjects to make sense of their connectivity to place and to guide their actions and projects accordingly’ (Dixon and Durrheim, 2000, p. 32). A ‘grounds of identity’ is hence understood in the double sense of a ‘belonging to place’ and a warrant through which particular social practices and relations are legitimized. Here, it is fair to say, identity and space are tied together via discourse; what I am referring to as ‘spatial subjectivization’ is thus understood as a result of subject-positioning. Such an approach is indicative of a broader trend in the field of cultural geography: the interpretative utilization of the central tenets of post-structuralism and discourse theory in conceptualizing the relations between space and power in ‘post-modern’ contexts.3

It is worth noting that discourse analytic approaches to the ‘space–power–identity’ relation have led much of the research in the (post)apartheid context that I focus on here, particularly in reference to issues of racist practice and the racialization of space (Dixon et al., 1997; Dixon and Durrheim, 2000; Dixon and Durrheim, 2003; Durrheim and Dixon, 2001). Given the predominance of this discursive approach in the South African context – along with the possibility that it is characterized by a number of explanatory weaknesses – it seems worthwhile considering a different, and indeed, properly psychosocial perspective on these issues.

Before turning our attention to a more detailed critique of the shortcomings of post-structuralist and discourse analytic engagements with space, it is worthwhile noting Lefebvre’s (1974) objections to those analyses of monuments that would treat them as predominantly the outcome of signifying practices. The monument, he states, can ‘be reduced neither to a language of discourse nor to the categories and concepts developed for the study of language’ (p. 222). The complexity of such a ‘spatial work’ must be understood as of a fundamentally different order to that of the complexity of a text. The actions of social practice, he advances – and this is a key point – ‘are expressible but not explicable through discourse’ (p. 222). Lefebvre’s suggestion thus is that in the analysis of monuments we need be acutely aware of ‘the level of affective, bodily, lived experience’ (p. 224). Emphasizing this argument he maintains also that

Space commands bodies, prescribing or proscribing gestures, routes … this is its raison d’être. The ‘reading’ of space is thus merely a secondary and practically irrelevant upshot, a rather superfluous reward to the individual for … spontaneous and lived obedience … [S]pace [is] … produced before being read … [not] produced in order to be read and grasped, but rather in order to be lived by people with bodies and lives in their own particular … context. (1974, p. 143)

What Lefebvre’s emphasis on the bodily and lived experience of space makes perfectly clear is that textual reading practices cannot grasp the particularity of an individual’s imaginative engagement with space, or the affectivity of this relationship. Extending this, one might comment that as important as the above discourse analytic approaches to space are, they fail to take into account the subject’s psychical (or libidinal) investments in particular places. For Lefebvre, relations of affect, ‘belongingness’ and spatial identification – what we might refer to as triangulations of space, power and subjectivity – may be importantly unconscious in nature, a case made by both Nast (2000) and, compellingly, Pile (1993, 1996). One is compelled here to ask: surely we must involve the unconscious in explaining the inter-relationship of power, space and identity, particularly so if these three are mediated by the force of ideology, a force, which, as we know, is typically less than rational in its functioning? This, I note, is not an isolated call; a variety of geographers have recently made the case for the importance of psychoanalytic approaches to the problems of conceptualizing the powers of space.4

The ‘inter-subjectivity’ of subject and space

Spatio-discursive approaches typically focus their attentions on space as resource, as a means of transmitting identity, that is, on spatiality as connected to, and extending a set of discursive technologies. By contrast, the work of Gaston Bachelard insists instead on the importance of the properly individualized identities given to places themselves....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: (Post)apartheid Psychosociality

- 1 The Monumental Uncanny

- 2 Apartheid’s Corps Morcelé

- 3 Retrieving Biko

- 4 ‘Impossibility’ and the Retrieval of Apartheid History

- 5 Apartheid’s Lost Attachments

- 6 Mimed Melancholia

- 7 Screened History: Nostalgia as Defensive Formation

- Conclusion: Time Signatures

- Notes

- References

- Index