- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book articulates the key theoretical assumptions of poststructuralism, but also probes its limits, evaluates rival approaches and elaborates new concepts. Building on the work of Derrida, Foucault, Heidegger, Lacan, Laclau, Lévi–Strauss, Marx, Saussure and Žižek, the book also provides a distinctive version of the poststructuralist project.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Poststructuralist Project

The main aim of this book is to explore the way poststructuralists endeavour to problematize and resolve some key dilemmas in modern social and political theory. But to address these challenges I need first to flesh out my conception of the poststructuralist style of theorizing. This requires an engagement with the founder of the structuralist problematic – Ferdinand de Saussure – and the way his ideas have been systematized by later structuralist theorists like Roman Jakobson, Louis Hjelmslev, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes into a fully fledged programme for the social sciences. I shall then consider the way poststructuralists have sought to extend the initial contours of the structuralist project. Here I focus on Jacques Derrida’s deconstructive readings of structuralist thinkers like Saussure and Lévi-Strauss, which he couples with his interpretation of Edmund Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology, so as to develop an alternative conception of grammatology or generalized writing. These classical poststructuralist themes and manoeuvres prepare the ground for the more substantive problems in social theory that are addressed in the rest of the book.

Saussure’s theory of language

Ferdinand de Saussure is best remembered for his Cours de Linguistique Générale (Course in General Linguistics), which was published in 1916 after his death. The book was based on notes of a lecture course delivered at the University of Geneva from 1907 to 1911. Although Saussure himself left few textual traces of the course, the book was derived from the notes gathered together by students who attended the lectures (see Dosse, 1997, pp. 43–7; Gadet, 1989). Equally, because the course varied considerably on the three occasions it was delivered, the book cannot be said to represent Saussure’s considered theory of language. Yet, despite its humble beginnings, the Course in General Linguistics is a revolutionary work that lays claim not only to furnishing linguistics with an authentic object of analysis but also in developing a distinctively structuralist approach to the human and social sciences.

As with any revolutionary theory, Saussure’s theory of language is complex and controversial. Yet he introduces four basic conceptual oppositions, which I shall use to focus my discussion of his approach. First, he privileges the synchronic over the diachronic study of language, in which the former consists of a system of related terms without reference to time, while the latter explores the evolutionary development of language. This does not mean, however, that Saussure ignores the transformation of language, as it is only when language is viewed as a complete system ‘frozen in time’ that linguistic change can be accounted for at all. Without the synchronic perspective there would be no means for charting deviations from the norm. Secondly, Saussure asserts that ‘language is a system of signs that express ideas’ – or langue – which consists of the linguistic rules that are presupposed if people are to communicate meaningfully (Saussure, 1983, p. 15). Importantly, langue is rigorously contrasted with ‘speech’ or parole, where the latter refers to individual acts of speaking. Saussure thus contrasts both the social and individual aspects of language, and he demarcates what he regards as the essential from the merely contingent and accidental. In other words, each individual use of language (or ‘speech-event’) is only possible if speakers and writers share an underlying social system of language.

The third basic conceptual opposition arises from the basic unit of language for Saussure: the linguistic sign. Signs unite a sound-image (signifier) and a concept (signified). Thus the sign dog comprises a signifier that sounds like d-o-g (and appears in the written form as dog), and the concept of a ‘dog’, which the signifier designates. A key principle of Saussure’s theory concerns the ‘arbitrary nature of the sign’, by which he means that there is no natural relationship between signifier and signified. In other words, there is no necessary reason why the sign dog is associated with the concept of a ‘dog’; it is simply a function and convention of the language we use. This does not mean that language simply names or denotes objects in the world, as this nominalist conception of language would assume that language consists merely of words that refer to objects in the world. Such a view implies a fixed, though ultimately arbitrary, connection between words as names, the concepts they represent, and the objects they stand for in the world. For Saussure, however, meaning and signification are entirely immanent to language itself. Even signifieds do not pre-exist words, but depend on language systems for their meaning. Given this, Saussure claims that the words in languages – or rather the rules of language – articulate their own sets of concepts and objects, rather than serving as labels for pre-given objects. This relational and differential conception of language means that the term ‘mother’ derives its meaning not by virtue of its reference to a type of object, but because it is different from ‘father’, ‘grandmother’, ‘daughter’, and other related terms.

This argument is fleshed out by two central principles: first, that language is ‘form and not substance’ and, second, that language consists of ‘differences without positive terms’ (Saussure, 1974). The first principle counters the idea that the sign is just an arbitrary relationship between the signifier and the signified, which suggests that signs simply connect signifiers and signifieds but are still discrete and independent entities. However, this would be to concentrate solely on the way signifiers literally signify a particular concept, thus disregarding the fact that Saussure also views language as ‘a system of interdependent terms in which the value of each term results solely from the simultaneous presence of the others’ (Saussure, 1974, p. 114). To explain the paradox that words not only stand for an idea but have also to be related to other words in order to acquire their meaning, Saussure introduces the concept of linguistic value, which he does via a number of analogies. Notably, he compares language to a game of chess, arguing that a certain piece, say the knight, has no significance and meaning outside the context of the game; it is only within the game that ‘it becomes a real, concrete element . . . endowed with value’ (Saussure, 1974, p. 110). Moreover, the particular material characteristics of the piece, whether it be plastic or wooden, or whether it resembles a man on a horse or not, does not matter. Its value and function is simply determined by the rules of chess, and the formal relations it has with the other pieces in the game.

Linguistic value is similarly shaped. On the one hand, a word represents an idea (entities that are dissimilar), just as a piece of stone or paper can be exchanged for a knight in chess. On the other hand, a word must be contrasted to other words that stand in opposition to it (entities that are similar), just as the value and role of the knight in chess is fixed by the rules that govern the operation of the other pieces. This means that the value of a word is not determined merely by the idea that it represents but by the contrasts inherent in the system of elements that constitute language (langue).

These reflections culminate in Saussure’s theoretical principle that in language there are only ‘differences without positive terms’. Here, language should not be seen as consisting of ideas or sounds that exist prior to the linguistic system, ‘but only conceptual and phonic differences that have issued from the system. The idea or phonic substance that a sign contains is of less importance than the other signs that surround it’ (Saussure, 1974, p. 120). However, this stress on language as a pure system of differences is immediately qualified, as Saussure argues that it holds only if the signifier and signified are considered separately. When united into the sign it is possible to speak of a positive entity functioning within a system of values:

When we compare signs – positive terms – with each other, we can no longer speak of difference; the expression would not be fitting, for it applies only to the comparing of two sound-images e.g. father and mother, or two ideas, e.g. the idea “father” and the idea “mother”; two signs, each having a signified and signifier, are not different but only distinct. The entire mechanism of language . . . is based on oppositions of this kind and on the phonic and conceptual differences they imply.

(Saussure, 1974, p. 121)

In sum, Saussure’s purely formal and relational theory of language claims that the identity of any element is a product of the differences and oppositions established by the underlying structures of the linguistic system.

According to Saussure, therefore, languages comprise systems of differences and relationships, in which the differences between signifiers and signifieds produce linguistic identities, and the relationships between signs combine to form sequences of words, such as phrases and sentences. In this regard, Saussure introduces his fourth and final conceptual division between the associative and syntagmatic ‘orders of values’ in language. These two orders capture the way words may be combined into linear sequences (phrases and sentences), or the way absent words may be substituted for those present in a linguistic sequence. In the sentence ‘The cat sat on the mat’, each of the terms acquires its meaning in relation to what precedes and follows it. This is the syntagmatic ordering of language. However, others can substitute for each of these terms. ‘Cat’ can be replaced with ‘rat’, ‘bat’, or ‘gnat’. Similarly, ‘mat’ could be replaced with ‘carpet’, ‘table’, or ‘floor’. This is what Saussure calls the associative ordering of language and is derived from the way in which signs are connected with one another in the memory (see Howarth, 2000a, pp. 18–22).

These principles of associative and syntagmatic ordering are manifest at all levels of language, ranging from the combination and association of different phonemes into words to the ordering of words into sentences and discourse. Thus Saussure analyses relations within and between different levels of language, while still employing the same basic principles. In so doing, Saussure proposes the founding of a new science – semiotics – ‘which studies the role of signs as part of social life’, where language is ‘simply the most important of such systems’ (Saussure, 1974, p. 10). Over time, this new science of semiotics laid the basis for the development of a unique structuralist methodology in the social sciences (Saussure, 1974, p. 16).

Structuralism in the human and social sciences

Thinkers like Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, and Barthes have thus produced structuralist accounts of a range of disparate social, cultural, and psychological phenomena. These include the study of interconnected myths in so-called primitive societies, the delineation of unconscious desires and fantasies that structure the identities and behaviour of human subjects, and the symbolic significance of everyday activities such as all-in wrestling and the semiotic function of fashion in modern societies. The latter arises from Barthes’s treatment of phenomena as diverse as social formations, political ideologies, myths, family relationships, texts, and wrestling matches as systems of related elements (Barthes, 1967; 1973). Saussure’s influence is also central for Lacan’s structuralist interpretation of Freud, though Lacan emphasized the ‘incessant sliding of the signified under the signifier’, thus problematizing the fixity of meaning and paving the way for a poststructuralist approach to social relations (Lacan, 2006, p. 419). The latter has been taken up by theorists such as Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Judith Butler, and Slavoj Žižek.

But the clearest programmatic statement of the new structuralist problematic is evident in the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. He argues that social relations in ‘primitive’ societies could be treated as if they were linguistic structures or symbolic orders. Consider, for instance, his theory of myth. In general terms, myths are repetitive, often oblique, tales that provide sacred or religious accounts for the origins of the natural, supernatural, or cultural world. They comprise fantastic stories of men intermingling with animals, fabulous events in the cosmos, and strange distinctions between apparently homogenous materials (Coward and Ellis, 1977, p. 18). Lévi-Strauss’s structural explanation of myth explores how it is that amongst the great variety of mythical tales across the world’s known societies they all seem to exhibit a basic similarity (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 208). He argues that myths cannot be understood discretely or in terms of the way they are told and disseminated in the various societies in which they occur. Instead, just as Saussure sought an underlying system of langue beneath the contingent acts of speaking, Lévi-Strauss argues that they have to be understood structurally by considering the underlying sets of differences and oppositions existing between their constituent elements.

The analogy with Saussure’s linguistic theory is not exact, however, because Lévi-Strauss introduces a third level of language to account for myths. ‘There is’, he argues,

a very good reason why myth cannot simply be treated as language if its specific problems are to be solved; myth is language: to be known, myth has to be told; it is a part of human speech. In order to preserve its specificity we must be able to show that it is both the same thing as language, and also different from it.

(Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 209)

According to Lévi-Strauss, parole and langue correspond to non-reversible and reversible time respectively, in which speech is the contingent articulation of words at a given time, whereas language is the ever-present system of language that makes speech possible. By contrast, myths constitute a more complex level of language, which combine the properties of parole and langue, and the reason for this is that while myths are told at particular times and places, they also function in a universal fashion by speaking to people in all societies (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 210).

What, then, are the basic constituent elements of myths? At the outset, myths are not to be confused with speech or language, as they belong to a more complex and higher order; their basic elements cannot be phonemes, morphemes, graphemes, or sememes. On the contrary, they have to be located at the ‘sentence level’, which Lévi-Strauss calls ‘gross constituent units’ or ‘mythemes’, and he endeavours to explore the relations between these elements. In his analysis of particular myths, these units are obtained by decomposing myths into their shortest possible sentences and identifying common mythemes, which are numbered accordingly. This will show, as he puts it, that each unit consists of a relation to other groups of mythemes. But so as to distinguish myths more properly from other aspects of language (which are also relational and differential phenomena), and to account for the fact that myths are both synchronic (timeless) and diachronic (linear) phenomena, mythemes are not simple relations between elements, but relations between ‘bundles’ of connected elements. After they have been differentiated and correlated together, Lévi-Strauss can then analyse myths at the diachronic and synchronic levels. He can observe and establish equivalent relations that occur within a story at different points in the narrative, while also being able to characterize the bundles of relations themselves and the relations between them (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, pp. 211–12).

An example that Lévi-Strauss gives to illustrate his analysis and method is the Oedipus myth as it appears in Greek mythology. The Oedipus myth is well known and is retold in different versions. Yet in outline, paraphrasing Thomas Bulfinch, it tells the story of Laius, King of Thebes, who is warned by the Oracle that his throne and life will be imperilled if his newborn son is to grow up. To avoid the prophecy, Laius commits his son to a herdsman and orders that the infant be killed. The herdsmen takes pity on the child, though not wishing to disobey the king ties the child by the feet and leaves him hanging from the branch of a tree. The child is discovered by a peasant, who takes him to his master and mistress. The master and mistress adopt the boy and call him Oedipus, or ‘Swollen-foot’. Years later, Laius, accompanied by an attendant, meets a young man on a narrow road, also driving in a chariot. After refusing to give way to the king, the attendant kills one of Oedipus’s horses, who in turn, in a rage, kills both the attendant and Laius. The young man is Oedipus, and thus unwittingly he murders his own father.

Shortly after these events, Thebes is afflicted by a monster called the Sphinx, which has the body of a lion and the upper part of a woman. The Sphinx lies crouched on top of a rock and accosts all travellers by proposing a riddle which if not solved results in immediate death. Though no one solves the riddle, Oedipus boldly takes on the challenge and after solving the riddle sees the Sphinx cast herself from the rock and perish. In gratitude, the people of Thebes make Oedipus their king giving him the hand of their queen, Jocasta, in marriage. Unknowingly Oedipus has killed his father and married his mother, thus fulfilling the tragic predictions of the Oracle. These horrors remain latent until Thebes is afflicted with a terrible famine and pestilence. When the Oracle is consulted again, the double crime of Oedipus is revealed. Jocasta kills herself. Oedipus, maddened with rage, tears out his own eyes and wanders helplessly away from Thebes abandoned by all except his faithful daughters (Bulfinch, 1981, pp. 143–4).

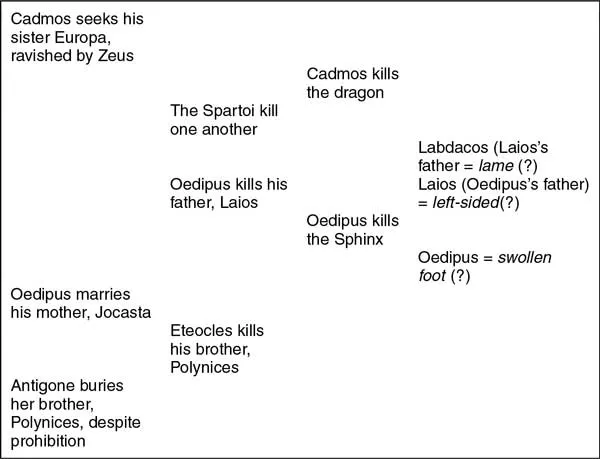

Figure 1.1 Lévi-Strauss’s Structural Analysis of the Oedipus Myth

Lévi-Strauss’s method of analysis is to disaggregate the story into its component mythemes and then to map them onto a table, which can reveal both its narrative structure and the related groups of mythemes. The resultant table is reproduced in Figure 1.1. This tabular representation enables Lévi-Strauss to read the myth as a story by disregarding the columns and simply reading the rows from left to right and from top to bottom. It also allows him to understand the significance of the myth by abandoning the diachronic dimension and reading ‘from left to right, column after column, each one considered as a unit’ (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 214).

Having decomposed the myth into its component mythemes, Lévi-Strauss is thus able to distinguish their common features so as to begin relating them together. According to his interpretation, the first column is characterized by ‘the overrating of blood relations’, whereas the second is a direct inversion of the first and represents ‘the underrating of blood relations’. The third column refers to monsters being slain, and the common feature of the fourth is the fact that they all connote ‘difficulties in walking straight and standing upright’ (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 215). What, then, of the significance of these relationships? Beginning with the relationships between columns three and four, Lévi-Strauss argues that the killing of monsters by mankind is inversely related to the first column, which signifies the autochthonous (or self-generating) origins of mankind. This is because the slaying of monsters refers to the denial of man’s autochthony, as the monsters and dragons represent obstacles that human beings have to overcome in order to live. Given this, the meaning of the fourth column is understood as a persistent belief in the autochthonous origin of man, the names capturing the particular characteristics of mankind when they are born ‘from Earth’. In sum, expressed in his distinctive mathematical idiom, Lévi-Strauss suggests ‘that column four is to column three as column one is to column two’ (in his preferred mathematical form: 4:3 : 1:2), and he argues that for primitive cultures ‘the inability to connect two kinds of relationships is overcome (or rather replaced) by the assertion that contradictory relationships are identical inasmuch as they are both self-contradictory in a similar way’ (Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 216).

The overall meaning of the myth for Lévi-Strauss is summarized in the following terms:

The myth has to do with the inability, for a culture which holds the belief that mankind is autochthonous . . . to find a satisfactory transition between this theory and the knowledge that human beings are actually born from the union of man and woman. Although the problem obviously cannot be solved, the Oedipus myth provides a kind of logical tool which relates the original problem – born from one or born from two? – to the derivative problem: born from different or born from the same? By a correlation of this type, the overrating of blood relations is to the underrating of blood relations as the attempt to escape autochthony is to the impossibility to succeed in it. Although experience contradicts theory, social life validates cosmology by its similarity of structure. Hence cosmology is true.

(Lévi-Strauss, 1977, p. 216)

It should be stressed that Lévi-Strauss is not concerned about the different variants of a single myth, or questions about whether myt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Poststructuralist Project

- 2. Problematizing Poststructuralism

- 3. Ontological Bearings

- 4. Deconstructing Structure and Agency

- 5. Structure, Agency, and Affect

- 6. Rethinking Power and Domination

- 7. Identity, Interests, and Political Subjectivity

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Poststructuralism and After by D. Howarth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.