eBook - ePub

Media and the Politics of Arctic Climate Change

When the Ice Breaks

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Media and the Politics of Arctic Climate Change

When the Ice Breaks

About this book

Combining multidisciplinary perspectives and new research, this volume goes beyond broad discussions of the impacts of climate change and reflects on the current and historical mediations and narratives that are part of creating this new social and scientific reality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Media and the Politics of Arctic Climate Change by Miyase Christensen, Annika E. Nilsson, N. Wormbs, Miyase Christensen,Annika E. Nilsson,N. Wormbs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Globalization, Climate Change and the Media: An Introduction

Miyase Christensen, Annika E. Nilsson and Nina Wormbs

An unusual voyage

In the summer of 2011, the tanker STI Heritage left Houston, Texas and made the long, arduous journey to Thailand, eventually arriving with over 60,000 tons of condensed gas.1 What made this trip special was not the start and end points (these are two major ports), but rather how, and how fast, the tanker made the journey. Instead of the traditional route via the Suez Canal, the STI Heritage picked up the condensed gas in Murmansk, Russia, and continued its journey towards Thailand via the Northeast Passage, a shipping lane running from Murmansk, along Siberia, ending at the Bering Strait. The use of this lane is, in and of itself, not unique, as historically portions of it have been navigable for two summer months each year. What made the STI Heritage voyage special, however, was the speed with which the vessel completed the entire route: eight days.2 This was a record for the Northeast Passage (broken weeks later by a gas tanker that made the trip in just over six days), which has seen a dramatic reduction of summer ice over the past decade, making commercial use of the lane economically viable, at least if one extrapolates from the numbers. In 2009, only two commercial vessels made the voyage. In 2011, that number had increased to 18.3

Texas and Thailand. When discussing the Arctic, these two regions of the world are likely not the first two to come to mind. Yet the case of the STI Heritage is a stark illustration of the degree to which a specific environmental question – the melting of Arctic sea ice – has been transformed from an issue of local concern in a region of the world that has been relatively neglected in media terms, to an issue with not only local and regional but also global implications. The case of the STI Heritage journey from Texas to Thailand also crystallizes how the reduction of sea ice in the Arctic region has been the catalyst for a discussion that goes far beyond the environmental. When the shrinking ice creates possibilities to reduce use of the expensive Suez Canal and to avoid the perilous coast of eastern Africa, it also constitutes a signal of ongoing geopolitical changes connected to global resource demands and trade patterns.

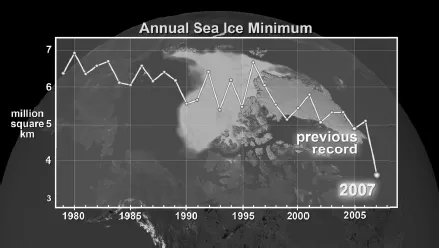

The satellite images from the sea-ice minimum of 2007 also marked the starting point for a shift in the regional political climate in the Arctic, where Arctic policies focus increasingly on security and sovereignty (Huebert et al., 2012). The new political climate has foregrounded not only the efficacy of political governance of climate change, but also scenarios of a future ice-free Arctic as a well-publicized media image of climate change. In August 2012, the Arctic sea-ice extent was on its way to reach an even more dramatic level, spurring yet another burst in media attention as the new satellite data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center were released to the press. The questions that emerged from the press and media stories about the declining ice concern not only the ice itself. The race for natural resources, new shipping possibilities and the risk for political and commercial conflicts over the Arctic are also among the issues that gained significance. These stories started to build momentum in the aftermath of 2007 making the sea-ice minimum a media story that is relevant far beyond the Arctic and far beyond global climate science and policy. Thus, as a moment with broad scientific and political consequences, the 2007 ice minimum warrants close attention, and a multivalent approach, in order to pinpoint key issues at the intersection of science, politics and the media in the overall study of global climate change. As will be discussed shortly, in media studies the concept of mediatization refers to the tightly interconnected nature of social processes and the media. With an effort to illuminate the intricate role the media play in both the representation of climate change and in public understanding of scientific and political questions, we will utilize the frameworks of mediatization and media events (and eventization) as conceptual instruments.

This introductory chapter sets the stage for six substantive chapters and a concluding chapter that approach the 2007 sea-ice minimum from a range of different disciplines. Together they convey local, regional and global perspectives as well as considerations from the points of natural sciences, history, anthropology, science and technology studies, and media studies. We seek to highlight, in particular, the increasing role of the media in framing the present-day Arctic and its future, and of climate change. Media in this context are more than the coverage in newspapers, television and other venues. We place the sea-ice minimum into an analytical framework that highlights the increasing role of mediatization (simply put, media saturation) as a prominent social trend in our late-modern societies. Mediatization is enmeshed with globalization, commercialization and individualization (cf. Krotz, 2007), making the media dimension more complex and worthy of interdisciplinary scrutiny. In what follows we discuss concepts such as ‘media events’ and ‘mediatization’ in relation to the broader theoretical and conceptual tropes of seeing the environment as a social construct and environmental politics as intrinsically intertwined with other areas of international politics.

The sea-ice minimum as a media event

The new commercial possibilities that have been highlighted in the wake of the declining sea ice are but one aspect through which the Arctic has become a unique showcase for global climate change over the past few years. The other ways through which the region gained visibility include mediated images of polar bears on small remnants of sea ice and dramatic footage of calving glaciers where the Greenland ice sheet is moving into the sea chunk by chunk – images that are used by scientists and environmental organizations in their efforts to raise awareness about the consequences of climate change. In the late summer of 2007, at the time of the ‘sea-ice minimum’, satellite technology played a key role in providing dramatic and influential images of the impacts of global warming in the Arctic when the data showed that the extent of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean had reached 23 percent below previously recorded low levels (2005) and 39 percent below the average over the period 1979–2000.4 Moreover, the sea-ice decline well surpassed what most climate experts had anticipated. As such, the images based on the satellite data provided a dramatic preview of a post–global warming Arctic geography that quickly intensified debate on and around global climate change, turning it into a media meta-event.

Figure 1.1 Sea-ice extent 1979–2007

Source: NASA.

In making the assertion that the sea-ice minimum was a ‘media event’, we construe ‘media event’ in the broader sense of a phenomenon, a moment, a ‘happening’ that draws significant media attention to the level of occupying considerable space in various forms and outlets of media. The concept was originally developed by Katz (1980) and Dayan and Katz (1992) in their bringing together both social scientific mass communication and cultural studies traditions to define the ways in which broadcast news covered certain instances and phenomena (cf. Couldry, Hepp and Krotz, 2009). In 1980, Katz wrote,

The paradigmatic media event is one organized outside the media but which may well be transformed in the process of transmission. ... The element of high drama or high ritual is essential: the process must be emotion-laden or symbol-laden, and the outcome be rife with consequence. (p. 3)

Dayan and Katz’s approach is one that looks upon media events as occasions ‘where television makes possible an extraordinary shared experience of watching events at society’s “centre”’, (Couldry, 2003, p.61). Fiske (1994) takes media events as discursive events (not merely intense discourse produced based on an occasion) and draws attention to the importance of transborder flows and the need to understand media events in relation to the level of their transborder character. There are many examples of such media events in politics, ranging from the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King in the 1960s to the more recent meta-event of the Arab Spring (see Christensen, 2013). With the aim of redeveloping the concept of media event in a global age, Couldry, Hepp and Krotz (2009, p. 9) argue that we need to understand media events not as products and mirrors of national cultures but of a highly complex global realm. The global realm is traversed by multiple nodes of connectivity (such as data and information flows) that influence both societal institutions (including media and politics) and the subjective domain of the public(s) and individuals. Put simply, in a global context both the production and reception of meaning/sense-making practices (such as media events) become more dispersed and complex. This necessitates correspondingly novel and multidimensional conceptual tools to capture both their character and due consequences.

Public debate about global climate change has also been closely linked with certain events, including the 1988 drought in North America and James Hansen’s testimony to Congress the same year that linked together scientific and popular understandings of climate change and set the stage for moving international climate politics forward at the time. More recent examples are Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2003 heat wave in Europe that killed almost 15,000 in France alone. As events that led to extensive media coverage of a range of issues on a global scale, they made apparent that adaptation to climate change was an issue of societal significance and would be a challenge also in rich countries with well-developed institutions.

While unexpectedness and immediacy (à la ‘breaking news’) are characteristic of certain events such as Hurricane Katrina or 9/11, media institutions and journalists also act as agents in lifting socially constructed moments (for example, the Copenhagen COP15 of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) to varying degrees and ranks of an event through their coverage. A similar dynamic applies to slower processes in nature such as retreating Arctic sea ice that only become events when they are constructed and mediated as such. An example is when press releases conveying satellite data are made public in ways and in a broader social and political context that grabs and further fuels media attention.

In understanding media events, the level and intensity of coverage is an important factor, but qualitative elements also factor in and should be accounted for to grasp the overall picture and ensuing impact in the long term. This echoes McComas and Shanahan’s (1999, p. 53) conviction that ‘it is not only the frequency of coverage, but also the character and form of that coverage that help to draw public attention’. Over the past two decades, there have been a variety of attempts, such as ‘mediatized public crises’, ‘media disasters’ and ‘media scandals’ to redefine and broaden the concept of media event through the use of related discursive constructs. In an effort to integrate media events and the concept of ‘mediatized rituals’, Simon Cottle (2008) suggests that the latter term refers to ‘those exceptional and performative media phenomena that serve to sustain and/or mobilize collective sentiments and solidarities on the basis of symbolization and a subjunctive orientation to what should or ought to be’ (Cottle, 2006, p. 415; see also Couldry, Hepp and Krotz, 2009).

The literature on media events highlights their increasingly global character, both in their production and in their reception (Couldry, Hepp and Krotz, 2009, p. 9; Hepp, 2004). Nationally confined and time-specific eventizations through live broadcasts (such as the Kennedy assassination, Woodstock or royal weddings) are hardly the primary constituents of the definition that should apply to ‘media events’ of today. More important is the ‘mobilization of collective sentiments and solidarities on the basis of symbolization and subjunctive orientation’ (Cottle, 2006, p. 415). Such a nuanced approach to media events offers a way to better grasp the 2007 and 2012 sea-ice minima, while a closer analysis of these events provides the empirical grounds to further theorize the mediatization of meta-phenomena such as ‘climate change’.5

In addition to periodically entering the visible realm of public debate by way of de facto events6 − quality moments such as headline-friendly disasters and groundbreaking scientific revelations − the climate debate on the whole embodies a truly longitudinal, meta character unlike other events of more momentous nature. As such, and recognizing the need to utilize a multidisciplinary approach to understand climate change in its totality, we propose a conceptual framework within which to approach climate change as a meta-event with the Arctic sea-ice minimum constituting a very significant moment along the way. As a meta-event, climate change is much more than the sum of its moments. It is akin to other phenomena that are socially and mediatively produced and absorbed as meta-events, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall or, more recently, the Arab Spring (Christensen, 2013). Thus the climate change debate, in and of itself, constitutes an institution that produces a multiplicity of scientific, political, popular and moral positionalities and contingencies across time and space.

Words, images and moments in media reporting

As discussed, the ways in which the media position climate change and its impacts have great significance. In the US context, for instance, skepticism towards a changing global climate is toned down if the label climate change is used rather than global warming, especially among Republicans (Schuldt, Konrath and Schwarz, 2011). And, just as the language about global warming matters, so do the ways in which global warming and its consequences are displayed through images, pictures, illustrations, maps, animations and so forth. The images surrounding the text are embedded in particular contexts that constitute the basis upon which our understanding and interpretation is built. One such example is discussed by Nina Wormbs in her chapter on the newspaper images illustrating the sea-ice minimum. These illustrations send different messages concerning what is impor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Globalization, Climate Change and the Media: An Introduction

- 2 Arctic Climate Change and the Media: The News Story That Was

- 3 Eyes on the Ice: Satellite Remote Sensing and the Narratives of Visualized Data

- 4 An Ice-Free Arctic Sea? The Science of Sea Ice and Its Interests

- 5 Signals from a Noisy Region

- 6 A Question of Scale: Local versus Pan-Arctic Impacts from Sea-Ice Change

- 7 Under the Ice: Exploring the Arctics Energy Resources, 18981985

- 8 Changing Arctic Changing World

- Index