eBook - ePub

Non-Standard Employment in Europe

Paradigms, Prevalence and Policy Responses

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Postwar employment standards are being undermined and 'non-standard' employment is becoming more common. While scholars have pointed to negative consequences of this development, this volume also discusses the evidence for a new and socially inclusive European employment standard.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Non-Standard Employment in Europe by Max Koch,Martin Fritz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Arbeitsmarktforschung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theoretical, Economic and Political Background

1

A Conceptual Approach of the Destandardization of Employment in Europe since the 1970s

Jean-Claude Barbier

Introduction

The present book addresses the issue of destandardization of employment. Employment is qualified as either standard or non-standard, while a social process is understood as transforming previously standard employment into forms of non-standard employment (NSE). Since the following terms may compete with other descriptions – atypical, precarious, vulnerable, and many other semantically connected terms used in various languages – these should first be reflected upon and this is the main goal of the present chapter. In our view, describing labour market developments in terms of ‘destandardization’ does not pre-empt any particular type of explanatory theory. The issue is generally linked to or even mixed with issues of ‘employment atypicality’,1 and sometimes ‘employment precariousness’ (Barbier, 2005a). These topics have been analysed for a very long time by many disciplines with the help of a variety of concepts. Initial important insights can be related to the literature on labour market segmentation of the 1970s and later, to the literature on flexibility of work and of employment. Sociology and institutional economics remained the main disciplinary location for this analysis and their literature extends over a period of about forty years. Recently, presumably partly inspired by mainstream economics, political scientists have addressed the subject; one of their prevailing perspectives is ‘dualization’ or ‘dualism’. Although they utilize differing methods and theories, both political scientists and mainstream economists share some key concepts: the simplistic opposition between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ is a remarkable case in point which will not be dealt with in this chapter (Knuth, 2011).

Considering the huge corpus of literature on employment destandardization, is it even possible to add anything significant to the discussion from a sociological perspective? Writing this chapter is an attempt to respond to this daunting challenge. Two empirical projects, typical of the 1980s and early 2000s (Rodgers and Rodgers, 1989; Laparra, 2004), explicitly addressed the question through a ‘precariousness’ lens. These remain relevant when one broadens the perspective to the question of ‘destandardization’. The latter perspective is interesting because it ‘de-politicizes’ the issue, at least apparently, whereas much of what has been published on precariousness, atypicality and more recently ‘precarity’ (Kalleberg, 2009)2 is heavily informed by normative judgments.

In standardization, as in standard employment (versus non-standard), lies the mundane notion of normality, of what is standard being perceived as typical, normal, usual, ordinary, habitual, expected, regular, but also established, quotidian and prevailing, as the rich list of synonyms in the Oxford English Dictionary indicates. Perhaps no other language expresses this meaning better than German with the notion of Normalarbeitsverhältnis (NAV). Simplifying the matter for comparative reasons, an employment relationship is generally viewed as normal, i.e. standard in Germany, if it fits certain criteria: it is permanent, full-time and social contributions are paid by both employers and employees. What is standard is however also linked to quality, and this provides another reason for using the term ‘destandardization’, because standard employment is also measurable in terms of certain qualities. A quality assessment adds an explicitly normative dimension to the description and, as will be seen, is linked to public policy and regulation.

As is common in comparative sociological work dealing with the usage and crafting of categories and concepts – whether in the former (normal) or in the latter meaning (matching a certain quality) – an approach to ‘standards’ brings to the fore the necessity of the relevant choice of levels of abstraction (Sartori, 1991), and another epistemological choice with regard to universalism (Barbier, 2005b; 2013). Sociologists always balance between very abstract generalizations and empirical documentation that lead to specifying variety and the contextual embeddedness of concepts. The approach we take in this chapter clearly prefers the concentration upon variety across countries instead of adopting a big-picture universalist approach with little concern for empirical data. Emblematic instances of the latter form of sociology, Richard Sennett and the ‘late’ Pierre Bourdieu,3 are interesting because they embody two equally universalist sociological traditions: the American and the French. In contrast, by drawing on our empirical research in many countries, we would like to situate a comparative sociological perspective that takes denominations and words seriously, and not only in English – the inescapable language of international research – but also in a selection of European languages. In sociology, being attentive to words in their original language brings many advantages (Barbier, 2013); as meanings evolve over time, one becomes aware that the significance attached to ‘standards’, ‘normality’, ‘(a)typicality’ and to ‘employment precariousness’ is profoundly embedded in history, in social norms and in political cultures.

In the first section, we will briefly link our reflection to what we see as the two main theories (on labour market segmentation and on flexibility of labour, work and employment) that explain the destandardization of employment. In this chapter, we unfortunately lack the space to analyse the consequences of the failure of social scientists to create a universal concept that is not too abstract, as the notion of standard employment inevitably must be. This has consequences in terms of the very tricky use of labour market statistics. In the second section, we will situate the issue of ‘standardization’ and ‘destandardization’ within their semantic relationships to other concepts used in many languages to describe what is normal in the field of employment. In the third section, we will show how the analysis of standardization and destandardization needs to be embedded into the wider perspective of social protection systems, institutions and political cultures; except at a very high level of abstraction, there is no such thing as ‘standard’ per se. This explains why addressing destandardization and the expansion of ‘atypical’ employment relationships has been very diverse across European countries. In this section we will also illustrate contemporary developments with the help of a few empirical examples; these show that concepts related to the labour market and social protection are strongly dependent on history and political cultures.

A common general interpretation of the causes of ‘destandardization’

For the last forty years and at a high level of abstraction, sociologists and institutional economists have largely analysed the process of destandardization in two directions. These two trends of research have provided convincing evidence of the reasons why forms of NSE emerged in the second part of the 1970s in many countries, i.e. when the standard forms of employment were prevalent in the majority of developed countries. Various theories of labour market segmentation involving the identification of companies’ strategies provide the first source. Social scientists have increasingly been attentive to stratification phenomena (employees, jobs) that were viewed as useful for the strategies of companies, with differences across sectors (stratification of jobs: wages, careers, status, education and training/qualifications, quality of working life) and, at the same time, to associated socio-political divisions (qualifications, skills, social capital) leading to multiple inequalities (see for example, Doeringer and Piore, 1971; Goldthorpe, 1984; Michon and Germe, 1979). Labour markets have thus increasingly been viewed as ‘segmented’, and a central aspect of destandardization today consists of multiple segmentations. From a more sophisticated perspective, the second strand of research has remained unchallenged: its main theoretical source stems from the ‘regulation school’ and its analysis of the flexibilization of work and employment, during times of changing monetary regimes (Boyer, 1986; Barbier and Nadel, 2000; Koch in Chapter 2 of this volume). Contrary to mainstream English-speaking research, this approach allows for the conceptualization of a ‘wage-earner nexus’ (rapport salarial) in Fordist societies, so that ‘jobs’, ‘employment’, or ‘employment relationships’ are not just ephemeral and random social forms that pop up in a particular country at a specific time, but are explained in terms of broader ‘accumulation regimes’. The search of capital for flexible work is crucially linked to international choices made by governments in favour of a deregulated monetary regime that fosters wage competition (not to mention the financial crisis). From the beginning of the 1970s, the consequences of this fundamental break with the Bretton Woods monetary regime is observable in the ensuing destandardization of different forms of employment. ‘Employment precariousness’ and ‘atypical’ employment soared in countries where Fordist norms had before gradually helped install ‘standard’ employment relationships in wage-earner societies (societés salariales). Regulation theory does not, however, explain in detail the variety of forms that the abstract destandardization of employment has taken over recent years and pays little attention to the empirical and precise functioning of societies, the creation and evolution of norms, specific institutions and political cultures. We will turn to these now.

Normality and standardization, atypicality and destandardization of employment

In Germany, the standard form of employment (NAV) was still dominant in the early 1990s (Laparra, 2004), when its closest French equivalent – the contrat à durée indéterminée (Permanent Contract; CDI) – was already becoming less common. In both countries, similar characteristics were the norm, and, indeed they are still the main norm today, although certainly less prevalent. Institutional forms and the way they are regulated4 correspond to the existing normative references in the two societies. Writing neither about ‘precarity’ or ‘precariousness’, Kalleberg (2000: 341–2) described NSE relations almost tautologically as ‘work arrangements’ that ‘depart from standard work arrangements in which it was generally expected that work was done full-time, would continue indefinitely, and was performed at the employer’s place of business under the employer’s direction’. An important element stressed by Kalleberg lays in the notion of ‘expectations’. The highly abstract traits of his definition of normality encompass this essential notion, which brought into being a variety of forms, depending on the period of time, country, region, industry, labour market segment, gender, age, etc. As we will see in the next paragraph, NSE is another way of labelling what is expected to be atypical in a particular society at a particular point in time. Second, before delving more directly into this diversity in the third section, our intention is to remain at a rather high level of abstraction of destandardization as it is viewed by two famous sociologists. Third, we will introduce the question of employment quality, or, as the comparable International Labour Organization (ILO) approach has termed it, ‘decent work’. At each step we will examine the diversity of approaches, of ‘expectations’ and the sometimes implicit, but always varying norms.

Atypicality: Another face of non-standard employment

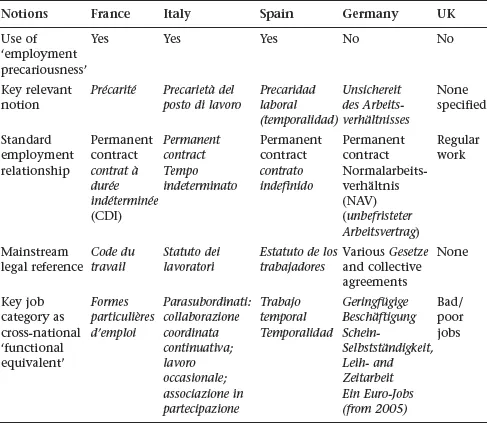

Of the indicators to objectify the ‘destandardization’ of employment three are most common: part-time employment; self-employment; and fixed-term employment (Table 1.1). Although ‘common’ across countries, these indicators cannot simply illustrate a homogenous cross-national view. Part-time work has become more and more typical across Europe, especially for women. Self-employment seems to respond to idiosyncratic histories and political cultures as the Italian and Polish cases demonstrate, while in Germany, it is often suspected of being quasi-self-employment (Scheinselbständigkeit). Fixed-term contracts widely differ in nature according to whether they provide access to social security entitlements or not. Nevertheless, a huge majority of the literature in the last thirty years has been content with repeating that atypical work or employment is a combination of these three. The European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) has shared this view for a long time. In their comprehensive review, de Grip et al. (1997) only considered part-time and fixed-term employment. To our knowledge, the comparative approach of ‘atypical’ employment has remained roughly unchanged over all these years, essentially updating the empirical evolution of the same indicators (Kalleberg, 2000). On the other hand, an interesting strand of literature has not focused upon the ‘typical/atypical’ opposition but on labour market careers (Davidsson and Naczyk, 2009) or on ‘transitions’ (Muffels, 2008) within these. This meant the question already raised in the wake of institutionalist labour market theories could be answered: whether or not people remain ‘trapped’ in ‘bad jobs’ throughout their working life. In this respect, one is inevitably drawn again to understanding the manifold interactions of management strategies, policies and social protection systems. Denmark stands as a case in point, with its high labour market mobility rates, its developed and informal system of training within the company, and a high level of equal access to social protection (in comparison with other systems).

Table 1.1 Comparing non-standard employment in five countries (prior to 2003–05)

The national bias of famous sociologists

From a Gallo-centrist perspective, it is surprising to find that the most widely known accounts of the transformation of work in ‘international expressive sociology’5 in the 1990s and well into the 2000s paid no attention to ‘precariousness’. While Richard Sennett (1999) for example, specifically addressed the consequences of flexibility on personal ‘character’, he did not use the notion of precariousness. His Anglo-American angle ignored the common French, Italian and Spanish perspective. On the other hand, from a typically Gallo-centrist perspective, Bourdieu (1998) noted ‘la précarité est partout’ (precariousness is everywhere) in one of his last books. Universalist views such as these did not erase national bias. It was then almost logical that, when translated in French, Sennett would write about ‘précarité’: in o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Preface by Richard Hyman

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Changing Employment Standards in a Crisis-Ridden Europe

- Part I Theoretical, Economic and Political Background

- Part II Country Studies

- Part III Comparative Perspective

- Index