- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reading Skin in Medieval Literature and Culture

About this book

Skin is a multifarious image in medieval culture: the material basis for forming a sense of self and relation to the world, as well as a powerful literary and visual image. This book explores the presence of skin in medieval literature and culture from a range of literary, religious, aesthetic, historical, medical, and theoretical perspectives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reading Skin in Medieval Literature and Culture by K. Walter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Art général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

WONDROUS SKINS AND TACTILE AFFECTION: THE BLEMMYE’S TOUCH

Lara Farina

Can “reading” skin let us touch it? Skin is, after all, both a medium for and a source of tactile sensation. Our own skin lets us be touched; the skin of others touches us. We can touch the things we read, and, as medievalists, some of the things we read really are skin. We are even talking more and more about the fact that parchment is skin.1 Yet we’re not talking much about what this reading feels like, even though touching manuscripts can yield valuable information about the way they were read. Worn areas, for example, guide us to places where medieval readers most often ran their fingers along lines of text; particularly stiff leaves suggest neglect or disinterest. Already understudied, these haptic interactions with textual skins may be even harder to come by as quick access to digital images replaces expensive visits to archives. While I think it crucial to bear in mind that digitization reduces the multisensory experience of parchment to a largely monosensory one, it is also imperative, given our need to work with visual reproductions, that we think about ways in which visual texts can inform us about the other senses. I am referring here to both medieval senses as they may be theorized or represented by medieval texts and our own “other” senses when we are touched by the embodied textual artifact.2

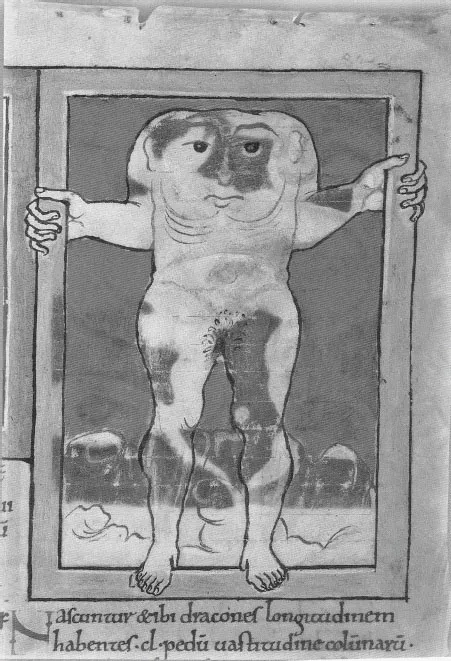

To consider the role that touch may play in reading medieval skin, I will discuss one particularly “manifold” image from a well-known manuscript, London, British Library Cotton MS Tiberius B.v. The image depicts a Blemmye (figure 1), one of the exotic races from the brief but memorable text now known as Wonders of the East.

Figure 1 A Blemmye © The British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r

While much recent scholarship sees this figure as representing a monstrous other for its eleventh-century English viewers, I draw attention to the way in which it offers us its enfolded, feeling skin. The Tiberius Blemmye’s skin is manifestly the skin of the manuscript, which not only touches our skin but also asks us to heed our haptic engagement with the moment of reading. In—or perhaps through—this illustration, tactile experience is not only conceptualized but also dynamically enacted with the reader as participant. Not surprisingly, it is an image to which scholars are drawn, and the affective relations between ourselves and the image must be part of this discussion. However, the Tiberius illustration is not unique in either its subject or its affective power. Blemmyae appear with some regularity in both illustrated travel narratives and at the edges of mappae mundi, and other strange bodies from the Wonders and related works are similarly fascinating. Thus, while I do argue for a new reading of this particular manuscript image, my engagement with its multiple skins may point us toward more tactically informed readings of wondrous medieval bodies in general.

* * *

A descriptive list of exotic places and their inhabitants, Wonders of the East is extant in three early English manuscripts: London, British Library Cotton MS Vitellius A.xv (the Beowulf Manuscript); London, British Library Cotton MS Tiberius B.v; and Oxford, Bodleian Library Bodley MS 614. It is illustrated in all three (though a portrait of the Blemmye is included only in Vitellius and Tiberius), and, together with a similar work, the Liber Monstrorum, the text has garnered significant attention in recent studies of medieval embodiment and visual culture. Full of curious creatures, from gold-mining ants to twenty-foot-tall people, and based in geographic imagination (“as you go toward the Red Sea . . . ”),3 Wonders lends itself well to a reading of its figures as expressions of early English ideologies of race and ethnicity, wherein the startling and sometimes grotesque variety of human and animal bodies contributes to Anglo-Saxon identity formation via the spectacle of difference. The visual rendering of the text’s exotica in sizable, framed illustrations (in all three manuscripts) further suggests the operation of the subjugating Western gaze on the abjected bodies of non-Europeans. Yet recent studies of Wonders, while reading its exotic peoples as monstrous others, have been careful to position such abjection as further entanglement with, rather than severance from, the Anglo-Saxon subject. These interpretations, following Kristevan theories of the abject, tend to argue that the division of Self and Other enacted by the verbal and visual texts is, inescapably, an incomplete one: the self constituted by exclusion must keep the excluded constantly in view, effectively incorporating it within.4 This subjective entanglement is, I argue below, what the Tiberius Blemmye performs most dramatically, but in a way that further complicates, and perhaps even contradicts, its use as a visual marker of ethnic difference.

Classical sources describing the Blemmyae, who are distinguished by their lack of a neck and head at the top of the body, do associate the figure with the margins of human form and culture, though not unilaterally.5 Pliny’s Naturalis Historia mentions them as one of the African tribes southeast of Ethiopia, and they also appear in Heliodorus’s third-century romance Aethiopica.6 Pliny’s description clumps the Blemmyae together with other peoples deemed marginally human because of their lack of key cultural elements:

The Atlantes, if we believe what is said, have lost all characteristics of humanity; for there is no mode of distinguishing each other among them by names, and as they look upon the rising and the setting sun, they give utterance to direful imprecations against it, as being deadly to themselves and their lands; nor are they visited with dreams, like the rest of mortals. The Troglodytæ make excavations in the earth, which serve them for dwellings; the flesh of serpents is their food; they have no articulate voice, but only utter a kind of squeaking noise; and thus are they utterly destitute of all means of communication by language. The Garamantes have no institution of marriage among them, and live in promiscuous concubinage with their women. The Augylæ worship no deities but the gods of the infernal regions. The Gamphasantes, who go naked, and are unacquainted with war, hold no intercourse whatever with strangers. The Blemmyæ are said to have no heads, their mouths and eyes being seated in their breasts. The Satyri, beyond their figure, have nothing in common with the manners of the human race, and the form of the Ægipani is such as is commonly represented in paintings.7

The passage clearly emphasizes what is absent, focusing particularly on impediments to cross-cultural communication. With its listless comment about the Ægipani’s form, the description perhaps even suggests that there is little point in further ethnographic inquiry here because the available sources are as complete as they will ever be. Pliny’s concluding remark a few sentences later drives home the sense of communicative limits: “Beyond the above, I have met with nothing relative to Africa worthy of mention.” Like Pliny, Heliodorus places the Blemmyae among groups like the Troglodytes, but his Aethiopica represents these as the decidedly human allies of the Ethiopians in their war against the Persians. Largely set in Africa, the romance depicts the region as both cosmopolitan and diplomatically engaged with the world at large. Thus, while the Blemmyae are mentioned only briefly in each of these late classical sources, and, though they are certainly portrayed as exotic in both, Heliodorus’s version suggests that the figure was not always associated with the limits of human identity as it is in Pliny’s more influential account.

Unlike Pliny, the textual description of the Blemmyae in Wonders of the East, provided in both Latin and Old English in the Tiberius manuscript, places them firmly in the human realm, noting rather brusquely that they are humans (“homines”/“menn”) without heads:

Est et alia insula in Brixonte ad meridiem in qua nascuntur homines sine capitibus qui in pectore habent oculos et os; alti sunt pedum. VIII. et lati simili modo pedum. VIII.

Đonne is oðer ealand suð fram Brixonte on þam beoð menn akende butan heafdum, þa habbaþ on heora breostum heora eagen 7 muð. Hi syndan eahta fota lange 7 eahta fota brade.

[Then there is another island, south of the Brixontes, on which there are born men without heads who have their eyes and mouth in their chests. They are eight feet tall and eight feet wide.]8

The mention of an absent feature, so fundamental to Pliny’s survey, is actually atypical for Wonders. Its description is generally accumulative, with recognizable, even familiar, bodily elements piling up into hybrid forms. In the item immediately preceding the Blemmyae, for instance, the Lertices are said to be animals having “donkey’s ears and sheep’s wool and bird’s feet” (p. 193). Coupled with creatures of great size (ants as big as dogs, twenty-foot people), great number (multitudes of elephants), or self-duplication (men with two faces on one head, beasts with eight feet), the hybrids of Wonders offer readers a morphology of sprouting hyperabundance.

The Blemmyae of Wonders may be “butan heafdum” but they are also granted a surplus of stature more in keeping with the work’s emphasis on robust embodiment (one can only assume that their 8’ x 8’ shape implies growth in all directions). The Tiberius illustration extends the text’s general additive impulses. Beyond the eyes and mouth, the illustration grants the figure ears, a nose, and even eyebrows in its torso, all the while retaining the anatomy of the chest itself, as we see in the lines marking the ribs. As Asa Mittman and Susan Kim observe of both the Tiberius and Vitellius illustrations of the Blemmyae, these are “recapitated” figures: “the head is clearly missing in a literal sense, and yet in another, is not missing at all.”9 What we see is an overlapping, doubled body, wherein the head is at the same time the torso. Further, as Mittman has argued, the sensory organs, scaled to fit a torso-sized “head,” are enlarged.10 The Tiberius figure is even excessive in its very relation to the illustration’s visual space, with its curiously “prehensile” feet and enlarged hands wrapping all the way around the frame meant to enclose it.11 It engages the v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- 1. Wondrous Skins and Tactile Affection: The Blemmye’s Touch

- 2. Noli me tangere: The Enigma of Touch in Middle English Religious Literature and Art for and about Women

- 3. Havelok’s Bare Life and the Significance of Skin

- 4. The Medieval Werewolf Model of Reading Skin

- 5. Cutaneous Time in the Late Medieval Literary Imagination

- 6. The Form of the Formless: Medieval Taxonomies of Skin, Flesh, and the Human

- 7. Discerning Skin: Complexion, Surgery, and Language in Medieval Confession

- 8. Desire and Defacement in The Testament of Cresseid

- 9. Touching Back: Responding to Reading Skin

- Works Cited

- Index