eBook - ePub

Sharecropper's Troubadour

John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union, and the African American Song Tradition

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

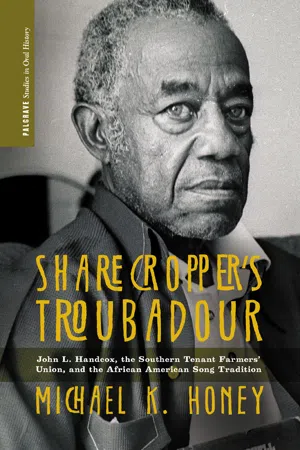

Sharecropper's Troubadour

John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union, and the African American Song Tradition

About this book

Folk singer and labor organizer John Handcox was born to illiterate sharecroppers, but went on to become one of the most beloved folk singers of the prewar labor movement. This beautifully told oral history gives us Handcox in his own words, recounting a journey that began in the Deep South and went on to shape the labor music tradition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sharecropper's Troubadour by M. Honey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

C H A P T E R 1

“Freedom After ‘While’ ”: Life and Labor in the Jim Crow South

My father used to tell me that things actually got worse after we was freed. During slavery, the master wanted to protect his investment. So he would give the slaves a place to sleep, a house, and food. When we was freed, they just let us loose, and didn’t care what happened to us. Whites started hangin’ and shootin’ blacks. They didn’t care anymore. The way I see it, under slavery we used to be the master’s slave, but after slavery we became everybody’s slave . . . [T]here has always been open and closed seasons on hunting and game, but there has never been a closed season for killing Negroes . . .

Everybody talkin’ ‘bout He’ben ain’t goin’ to He’ben. They sang that in church quite a bit back in my childhood days. We had a grace too: Lord, keep our neighbors back, until we eat this snack. If they come among us, they’ll eat it all up from us. (laughs)

—John Handcox

Did Sanctioned Slavery bow its conquered head

That this unsanctioned crime might rise instead?

—Paul Laurence Dunbar 1

On February 5, 1904, John Handcox entered into the world a supposedly free man. He was born on a farm two miles southwest of Brinkley, on the road to another little town called Clarendon, in the hill country of Monroe County, Arkansas.2 More than a generation before, his people’s struggles and a deadly Civil War had ended the long nightmare of America’s racial slavery, one of the worst forms of labor exploitation in human history. However, in John’s lifetime, African Americans in the South still faced a regime of shocking white brutality and labor exploitation. John grew up in one of the hardest places and at one of the hardest times to be black in America.

Like his enslaved ancestors, John drew upon a musical culture of resistance and struggle for survival. Since the first ships brought them from Africa, slaves had created religious songs with haunting and beautiful melodies. Abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass wrote of these songs that “every tone was a testimony against slavery.” In The Souls of Black Folk, published the year before John Handcox was born, scholar W. E. B. DuBois, himself a descendant of slaves, called them “the sorrow songs,” in which “the slave spoke to the world” with “a faith in the ultimate justice of things.” Whites often regarded these as songs of resignation or of happiness that focused solely on the hereafter, but Douglass wrote that “it is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are unhappy.” Scholar and theologian James C. Cone wrote, “So far from being songs of passive resignation, the spirituals are black freedom songs which emphasize black liberation as consistent with divine revelation.” The black song tradition more often affirmed deliverance, transcendence, and redemption rather than despair. African Americans gave to the nation “a gift of story and song,” creating a “stirring melody in an ill-harmonized and unmelodious land,” according to DuBois. 3

John Handcox followed the black song tradition, adapting inherited melodies and words that migrated from one tune to the next. Slave songs offered gifts of the heart to provide comfort, but sorrow songs also clearly called for freedom. Songs such as “Steal Away,” “No More Auction Bloc for Me,” “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?” and others may have had their origins as slaves fought for their emancipation during the Civil War.4 At the Library of Congress in March of 1937, Handcox recorded one such song, a traditional spiritual commonly titled, “Oh Freedom!” John flattened out the melody line and sang it in a plaintive voice, always repeating the first line twice:

No more mourning,

no more mourning,

no more mourning after ‘while . . .

John created each new verse by changing one word, and each one signified the travails experienced daily by generations of people who had lived through slavery and its aftermath, the racial apartheid system of Jim Crow:

No more cryin’ . . .

No more weeping . . .

No more sorrows, Lordy . . .

I know you’re gonna miss me . . .

No more sickness . . .

No more trouble 5

In the 1960s, civil rights movement singers popularized this song as “Oh Freedom!” and ended each verse with the traditional wording, “And before I’d be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave, and go home to my lord and be free.” John, however, sang the chorus of the song this way:

Oh freedom, oh freedom, oh freedom after ‘while,

And before I’ll be a slave I’ll be buried in my grave

Take my place with those who loved and fought before.

When asked where he got this version of the song, John said simply, “I always sang it that way.” The radical white preacher Claude Williams pinpointed the origins of John’s version of the chorus as he reminisced about a conversation he and John had in a car when they worked together organizing the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) in the 1930s. “As we talked . . . we decided that people who first had sung that song could not really have lived unless they fought.” Instantaneously, John interjected his new closing lyric, “take my place with those who loved and fought before.”6

John wrote many original songs and poems, expressing in vivid language the miseries of poor people and his hope that they could change their lives through organizing. He also adapted older, traditional songs such as this one, well aware that his own life was embedded in a train of events and experiences handed down by those who came before. “Freedom after ‘while” provided a subtle comment on the uncertain future and unfinished character of the freedom struggle that he and his family endured in hopes of making freedom real, someday.

Slavery and Its Aftermath

A lively man with a quick laugh and many jokes, John Handcox also had a serious story to tell. Recalling the oft-stated maxim, “kill a mule, buy another, kill a nigger, hire another,” John commented, “They had laws against killin’ squirrels—there’d be certain seasons you coud kill squirrels—there’d be certain seasons you could kill squirrels, but it was always open season on black people.” While blacks lived in fear for their lives, whites often claimed to exercise a sense of paternalism toward slaves. But John knew from his maternal grandfather that the legend of white paternalism was false. John’s grandfather spoke of slavery’s exploitation and violence and the bitter divisions that most masters inculcated among the slaves. “I remember him telling me how the slaves they all stucked together if one or some of the slave would try to get away,” but at other times “they would capture them and return them to their owners.” 7 To understand his life, John insisted, one must start from the beginning:

The first thing we want to talk about is . . . the way the Negroes, or the black people you might say, was, how they come to the United States. They was brought here from Africa. The whites went out and captured them from Africa and brought them over here and used them as slaves for years. My grandfather, that is, my mother’s father, used to sit down and talk, and I’d listen and ask him questions about slavery and everything. He’d point out about how the slaves had to work. The old master had ‘em workin’ and cay’in’ [carrying] big logs. Sometimes they’d be cay’in’ logs [and] they couldn’t see each other over them, they’d be so big. They’d pile ‘em up and burn ‘em, or make a bit of lumber out of ‘em. Anyhow, I’d ask him different questions about being a slave, and he would look like he’d get pleasure out of talking with me about it.

He would tell me how the old bosses used to have the big healthy slave men for breedin’ with the young slave girls, somewhere around 15 or 16 years old. They’d do that just like breedin’ horses or anything else that you want to try to breed the best for the market, like horses and stallions at a racing stable. I don’t know if they were interested in the color of a slave so much. I don’t know if color made a difference. Most who were bred were dark, I think. I never heard him saying anything about cross-breeding white and black. My grandfather was a slave in Alabama, born in Alabama. He was a big, husky, stout guy. He said they had women during that time, that’s what they used him for. They had the big stout men breed these young girls to grow these big men.

John’s ancestors had been part of a stream of African Americans dragged as slaves into Mississippi and Alabama from points further north and east, as the expansion of cotton production built the nation’s wealth and created an affluent and increasingly aggressive slaveholder class in the Deep South.8 His family’s genealogy is sketchy. The spelling of the last name on the paternal side of John’s family changed repeatedly: from Hancock, to Handcock, and, in John’s generation, to Handcox. However, first names such as Vina, Willis, Lizzett, George, Liza, and Ben showed up repeatedly, linking one generation to the next among John’s siblings and offspring.9 Census records indicate that John’s paternal grandfather, who he never met, was born in Mississippi in 1852. His maternal grandfather told John about his own travails in slavery, and uncles and aunts told him of their migration into Arkansas from the Deep South.10 Clearly, his own life was rooted in the slavery and post-slavery experience.

His grandparents’ generation began their lives during what DuBois, in his book Black Reconstruction, called the “general strike” of slaves that helped to destroy the Confederacy, 11 and also experienced the turmoil that followed the war. They had hopes for landed independenc, as federal troops seized plantations and let former slaves divide them up or farm them cooperatively, but Andrew Johnson took Abraham Lincoln’s place as president after his assassination and returned confiscated lands to slave owners. Former slaves had freedom but no land or money, while plantation capitalists had land but needed black labor—yet no longer felt any obligation to feed or house their former slaves. John wrote, “The way I see it when we were slaves we were valuable but when we became free we lost our value. We were not freed we were taken out of a pen and put in a pasture and they said to us root, hog, or die a poor pig.”12

Ex-slaves went on the move, seeking literacy, family reunification, civil and political rights, and above all, land and a degree of economic independence. John’s elders fled the Deep South hoping for a better life in Arkansas.13 John recalled his family’s migration through the stories told to him by his maternal grandfather:

He was on a big plantation farm, and when freedom came, he moved the family to Arkansas in a covered wagon. They used to have lots of covered wagons. He just wanted to get out on his own, the way I understand it, to get out from that part of the country. He had married, and he had three children, and he had some mules or horses, I don’t know which one. He fixed him up a covered wagon and drove it from Alabama to a little place in Arkansas named Brinkley. He raised a little cotton and corn, and he farmed. He learned how to make cross ties and made those, and he sold wood to provide for his family, plus his little farmin’. He bought 60 acres of his own that he worked. That’s where he stayed until his death. I never heard my grandfather say anything about his parents. He brought a first cousin along with him. He had a sister older than him, in Hot Springs, and a nephew he sent back for later in Alabama after he got out here and settled down. My dad’s father I never seen.

John did not know much about his father’s side of the family, but he knew it had something to do with his high cheekbones and a light brown complexion. He elaborated on his mixed racial heritage:

My father’s mother was half white. Her mother’s master was her daddy, and her grandfather was white. I’ve seen her half brothers and sisters, they was his. They lived in a little place called Cotton Plant, Arkansas. My grandmother, though, she hated them. She knew they knowed that she was their sister, and they would call her “Aunt Lizard.” Her name was Lisabeth, and they wanted her to come and work something for ‘em. She went once to my knowledge, and after that, she didn’t go no more. Her daddy didn’t make no allowance or nothing for her. She had sisters and brothers as rich as cream but they never did give her nothing. Treated her like their maid, and she resented. I don’t know nothin’ about her brothers and sisters except her white brothers and sisters.

My mother’s mother was full Indian. She was a beautiful lady. She was Blackhawk or something, but don’t hold me to it, I don’t want to tell the wrong thing. She was from Alabama. That’s where her and my grandfather married. They had as many as three or four kids when they come to Arkansas, but they [eventually] had 14 in all. I was six or seven years old when she died. I can remember her well. My [maternal] grandfather lived with us and he passed in ‘33. He was 80 some years old when he passed.14

The Census Bureau in Arkansas in 1900 listed ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Music, Memory, and History

- CHAPTER 1 “Freedom After ‘While’ ”: Life and Labor in the Jim Crow South

- CHAPTER 2 Raggedy, Raggedy Are We: Sharecropping and Surviva

- CHAPTER 3 The Planter and the Sharecropper: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union

- CHAPTER 4 There Is Mean Things Happening in This Land: Terror in Arkansas

- CHAPTER 5 Roll the Union On: Interracial Organizing in Missouri

- CHAPTER 6 Getting Gone to the Promised Land: California

- CHAPTER 7 “I’m So Glad to Be Here Again”: The Return of John Handcox

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index