eBook - ePub

How to Make Boards Work

An International Overview

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Make Boards Work

An International Overview

About this book

How to Make Boards Work offers a unique view of the thinking and doing of governance. The outside-in perspective offers a holistic framework highlighting how global cultural, social and political diversity impact boards of directors. The inside-out perspective emphasizes how governance and boards can effectively realize sustainable value creation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Make Boards Work by A. Kakabadse, L. Van den Berghe, A. Kakabadse,L. Van den Berghe,Kenneth A. Loparo,Lutgart Van den Berghe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The ‘Outside In’ Perspective

1

Exposing the 20th Century Corporation: Redesigning 21st Century Boards and Board Performance

Nadeem Khan and Nada K. Kakabadse

Introduction

Governance oriented boards are prevalent across different economic systems (Hall and Soskice, 2001), cultures (Hofstede et al., 2010) and national boundaries (single/dual structure) in which they are the leading clique within private, not-for-profit, public and hybrid organisations (Hermalin and Weisbach, 2003). Their purpose goes beyond regulation (Aguilera and Jackson, 2003), ameliorating the agency problem (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Berle and Means, 2009/1932) or shareholder wealth maximisation (Friedman, 1962) to balancing society’s needs and wants in a virtuous and accountable manner (Aristotle, 384–322 BCE; Smith, 1759). However, the emerging wider impacts of the corporation suggest deep concerns about the performance and management of board-directed organisations with respect to market dominance (Kim, 2012), lobbying dynamics (Child et al., 2012), board remuneration (Gregory-Smith and Main, 2012), financial management (Berger et al., 2012), competitive behaviour (Porter, 2009) and political power struggle issues (Cutting and Kouzmin, 2002).

In this regard, we know very little about boards themselves, as they have operated largely behind closed doors (Useem, 2003) and have traditionally had little active involvement in a corporation’s daily affairs (Scherrer, 2003). More importantly, we cannot understand boards in isolation (Useem, 1980). We require a holistic lens to critically appreciate the historical development, ongoing selective influences (Lewin and Volberda, 2003) and geo-political factors at play before peering into the boardroom itself to understand the detailed processes and issues that make a board work.

An overview of the corporation

Take care of Fire, learn from Water, co-operate with Nature.

Motto of Hoshi Ryokan,

718 A.D. World’s oldest currently operating company (46 generations)

718 A.D. World’s oldest currently operating company (46 generations)

The world’s oldest continuously operating family firm, Buddhist temple builder Kongo Gumi, closed in 2006 after 1,400 years. The firm had succumbed to an excessive $314 million debt, which resulted from the 1980s property bubble, coupled with social change in Japan (The Economist, 2004). Takamatsu Corporation purchased the assets. Thus, the prestige of this title has been passed to Hoshi Ryokan (718 A.D.). In this regard, family businesses have outlasted governments, nations and cities (O’Hara and Mandel, 2004) and contribute 70% to global GDP (Family Firm Institute, 2012). However, only 16% survive beyond a generation (Davis, 2012). In the 20th century, some of the survivors have emerged as corporations benefitting from financially liberal market forces (Useem, 1980). In this regard, the world’s leading 2,000 corporations currently employ 83 million people, have $149 trillion in assets and generate $36 trillion in revenue (Forbes, 2012). However, although these corporations represent 46% of global GDP (Economy Watch, 2010), one-third of the Fortune 500 corporations that existed in 1970 disappeared by 1983 (Investopedia, 2011).

The term ‘corporation’ derives from corpus, the Latin word for body or body of people, or corparoe, the Latin word for physical embodiment. The essence of body of people infers communities, shared collaborative understanding and common purpose. We can recognise the holistic embodied form whereby the parts contribute to the whole. In the historical business context (Hickson and Turner, 2005), Roman law (500 B.C.) recognised a range of corporate entities which included state and private bodies (universitas; corpus; collegium) in commenda form, or simply stated, a form of trust in which one delivered goods to another for a particular enterprise. We associate the modern context of the origins of the corporation (Brown, 2003) more so with feudal and monarchist governments that introduced legislation to enable shareholding. Mercantilism was alive and well. An example is Russia. In 1557, this nation granted monopoly rights for trade functions and risk management. The British East India Company was an English and later (from 1707) a British joint-stock company and megacorporation that pursued trade with the East Indies, but which ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent. The American government enacted the first limited liability law in New York (1811). This concept eventually spread to the UK in the form of the Limited Liability Act of 1855, and further across much of Europe.

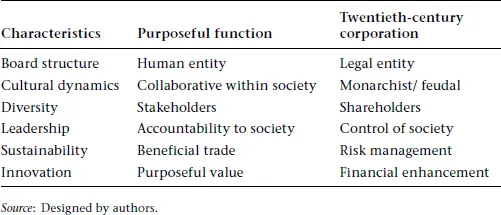

As such, Stora Kopparberg is one of the oldest industrial corporations. Established in a copper mining community in Sweden in 1288, it merged with Stora Enso, the Finnish integrated group of companies, in 1992. The historic mine has become a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. We note that Adam Smith wrote his Wealth of Nations (1776) not long after the East Indian Company’s 1772 collapse. By the beginning of the 19th century, the US and UK governments had granted increasing rights and progression of legislation in their charters along with associated governance of these bodies. Interestingly, Berle and Means published their seminal work, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (2009/1932), not long after Black Tuesday (29 October 1929). Thus, over time, the corporate charter has developed, while the essence of collaborative purpose and communities has degenerated, leaving the corporation to become an artificial, transferable and immortal legal entity separate from human form along with its accountability and regulation of behaviour. The recent 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) may provide us with an opportunity to reconsider The Wealth of Nations (Smith, 1776) and the board’s role (Berle and Means, 2009/1932) from a new perspective as the characteristics of the corporation (Table 1.1) appear to be at odds with its purposeful function in society.

Table 1.1 Internal corporate characteristics

Corporate cyclical change

Merck is the oldest chemical and pharmaceutical company which dates back to 1668 (Germany), whilst in the United States, some of the oldest companies include General Electric (1876), Bank of New York (1784), Cigna Insurance (1792), JP Morgan (1799) and Dupont (1802). Interestingly, a recent Japanese database survey by Tokyo Shoko Research (2009) of 2 million companies determined that 21,666 companies are older than 100 years. Further, according to the Bank of Korea, firms older than 200 years include 3,146 Japanese firms, 837 German firms, 222 Dutch firms and 196 French firms. Notable UK firms include the Royal Mail (1516), Bank of Scotland (1695), Oxford University Press (1586), Schweppes (1783) and Harrods (1835). This makes today’s household corporate names such as Microsoft (1975) and Facebook (2003), which boasts 1 billion users in 2012, the new chariots of global cyclical technological change in society. We may ask, had it not been for those years ago, teenagers Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerman, would we be just replacing the names or the phenomena? What forms will these or new emerging corporations take in a hundred years from today?

Nevertheless, our society’s corporate elders, such as the China Gas Company (1862), Nestle (1866), Hong Kong and Eu Yan Sang (1873), Unilever (1885), Great Eastern Life Assurance (1908), IBM (1911) and Rolls Royce (1914) and their extended economic supply chains and networks across the globe are continuously challenged to innovate and renew their value to society (Schumpeter, 1934) or suffer the ecological inevitability of systemic rebalancing (Adner and Kapoor, 2010; Kapoor and Lee, 2012). In the 21st century post-GFC era (Knyght et al., 2011), this is evident in the nationalisation and collapse of the banking sector. Take for example, the Royal Bank of Scotland, which is now 82% owned by the UK government, whilst Lehman Brothers became the largest bankruptcy filing in US history and Northern Rock had a bank run on 14 September 2007 as news spread that it was seeking emergency funding from the Tripartite Authorities. Lloyds TSB, founded in Birmingham, UK, in 1765, and the US-based Citibank, which began in New York in 1812, are both among the wounded. Since the financial crisis implosion from within the United States in 2008, 457 Banks just within the United States have failed (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2012).

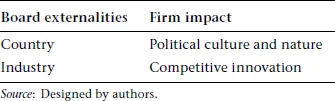

Beyond the corporate institution, in highly regulated, educated and developed 21st century societies (Table 1.2), it seems very odd that government institutions can freely create excessive debt (The Economist, 2012) without society questioning the decision makers about where the money is coming from and under what terms. Take for example, Greece, Ireland, Italy and Spain, who in recent months have all sought extended bailout funds from the European Central Bank (ECB). The United States recently announced its third quantitative easing programme (Katasonov, 2012) and critics have pointed to Greece’s recent bailout as the nation continues to maintain a proportionally large defence budget (Lendmenl, 2012; Smith, 2012). Whilst neo-liberal governments continue to increasingly burden the next generation’s tax payers, forecasts suggest that just to reduce national debt to 60% of GDP, which economists regard as a manageable level, will take Japan until 2084, Italy until 2060, France until 2029 and the UK until 2028 (Ventura and Aridas, 2012). The deeper question is whether democracy is working – considering that start-up businesses cannot obtain loans, but bank bailouts and government debts are spiralling. Further, it appears that the only real dialogue of value in competitive democracies takes place just before an election.

Table 1.2 Externalities of the corporation

As such, during 2008–2012, governments spent an extra $2.4 trillion due to the GFC, of which $1.9 trillion went to developed countries (two-thirds of this to banks). In contrast, the $500 billion that governments spent in developing countries went to manufacturing, education and health industries. In the East, although the Chinese and Indian economies have recently benefited from the extended forces of neo-liberalism (Xu, 2011) and mass consumerism (Gerth, 2010), the concern is whether capitalistic history is repeating itself within these highly populated regions of the world. Is the East learning from the West’s sharing of ecological/technological advanced lessons? What are the far-reaching global impacts as the current growths of these economies slow down to reveal a new reality? In 2010 the developing countries China, India, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia received greatest inflows of capital and grew by an average of 8.4% (Forbes, 2012). We note the ongoing global economic hubs’ transition towards the East (Wolfensohn, 2010) as evident by Petro China becoming the first $1 trillion corporation (Seattle Times, 2012) and the world’s largest global corporation in 2007 (Stainburn, 2012). In contrast, the US debt is officially at $16 trillion (2012) and a recent report has posited that it may more realistically be $50 trillion (Campbell et al., 2012).

The corporate geo-political phenomena

For us to have a deeper understanding of these social, natural and scientific phenomena, we must appreciate that the catalysts for 20th century corporations to develop have been major global events such as European feuds (World War I), emerging nationalistic tendencies (World War II) and apartheid in South Africa (1848). Over the centuries, these events have crystallised from within the complex Anglo-American bilateral relationship (1607–present) and European colonial intentions towards resources (Dutch, French, UK), among other geo-political shifts within society (Useem, 1980). However, the associated costs have been considerable and long-lasting. We have seen 160 million war casualties in the 20th century (Scaruffi, 2009). At the same time, renewed industries such as textiles, railways, coal mining and information technology have spawned and expanded.

The academic literature in Western management commonly refers to the corporation (Drucker, 1972) and its internationalisation patterns, exemplified by the East Indian Company (1602–1778), from an economic shareholder perspective (Friedman, 1962). In this respect, the more open-minded and liberated scholars have appreciated and progressed the more meaningful notion of stakeholders (Freeman et al., 2010), whilst ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I The Outside In Perspective

- Part II The Inside Out Perspective

- Index