eBook - ePub

Beyond the Low Cost Business

Rethinking the Business Model

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond the Low Cost Business

Rethinking the Business Model

About this book

Clients are consistently demanding lower prices at the time of each purchase and companies can only react by reducing costs. This volume shows that the only way to do this, is to reinvent the business model. New consumers, new pricing, new brands, new strategies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond the Low Cost Business by Kenneth A. Loparo,Josep Francesc Valls Giménez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Birth of the Low-Cost Phenomenon

As had already happened with US air-traffic deregulation in 1978, the European low-cost phenomenon first appeared in the wake of the price war between certain airlines attempting to break into the market following European air-traffic deregulation in 1997. Another cause was the widespread demand for low prices on the part of consumers as a result of heightened price sensitivity. The confluence of supply and demand, which came about over the last decade, caused the position of price as a deciding factor in the valuation of a product to change definitively. Where it had once been towards the end of the pre-purchase process, it now had a new, pre-eminent position as the absolute initial purchase discriminator, at the moment that the purchase is first conceived.

We can divide the phenomenon into two main periods. The first spanned 1997 to the mid-2000s, from air-traffic deregulation and the boom in low-cost airlines and tourism in general, up to when the phenomenon incorporated powerful mass-market hard discounts, with the focus on the base price and little thought given to questions of value. The second period extended between the mid-2000s and 2010, covering the definitive expansion of the phenomenon into all European financial sectors; customers still demand a price, but they associate it with specific values. This was a decisive moment for “pricing for value”. During this second stage, the phenomenon received expansive coverage in the mass media, particularly with the advent of the crisis of 2008.

1.1 1997 to 2004

The deregulation of European air transport in 1997 is regarded as the low-cost phenomenon’s starting point. A number of companies took the opportunity to break into the market by significant price differentiation. Up until then, companies had operated like national airlines. These were national strategy, low-return companies, with intensive use of capital and static, full-price techniques. The pricing model seemed to be costbased, although any similarity to that system was purely coincidental. Then new companies began to offer no-frills prices, corresponding to basic, dynamic, cheap products, and with costs cut on all sides. The first low-cost airlines were characterised by the offer of point-to-point transit while the classic companies all specialised in spoke–hub distribution networks. According to this categorisation (Campa and Campa, 2009), the first model is characterised by intensive use of assets, reduction of turnaround times and low labour and operational costs, while in the second, the traditional company network structure, favours maximisation of the number of markets served, connecting traffic, sophisticated products and high economies of scale (among other factors), but does have the disadvantages of congestion, delays and a need for greater investment in infrastructure.

The first low-cost companies had seven success factors in common:

(1) Cost reduction all along the value chain. The savings these companies made compared to the established companies were, basically, the following:

Lower taxes, slots and handling costs, through landing in smaller airports or hangars, which are proliferating across European air travel;

A faster turnaround, meaning lower maintenance costs on the ground and planes making more flights per day;

More seats where there had been fewer, wider seats;

No free extras; the extras offered previously became new sources of income, like all those activities created around the Internet which provided a new income;

Tickets issued from the airline’s website, which cut out the travel agent’s commission, the paper (when it was used) and the process of making the actual ticket, as well as the costs connected to an advertising campaign, which was unnecessary;

Everything connected to the salaries and expenses of the cabin crew and the ground crew, whose costs were drastically cut as a consequence of every crew returning to base every night, and pay conditions being much more to the advantage of the companies, unlike the established airlines where absolute power in the negotiations was in the hands of the staff (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 LCC cost reductions

Concept | % Reduction |

Secondary airports, taxes, timetables, slots | 6 |

Third-party handling or self handling | 10 |

Turnaround 15–20, compared to 45–55 | 3 |

Lower seat density | 16 |

No frills | 6 |

Electronic ticket | 6 + 3 |

Fewer staff and contracts with incentives | 3 |

Fleet standardisation (Boeing 737) | 2 |

High rebooking and excess baggage fees |

Source: Author’s own from the European Cockpit Association.

(2) Outsourcing all non-core business tasks, to strip the company structure down to the minimum. This meant a compact management structure, cabin and ground crew reduced to the absolute minimum, rented headquarters and equipment, and mass subcontracting of all services outside the company.

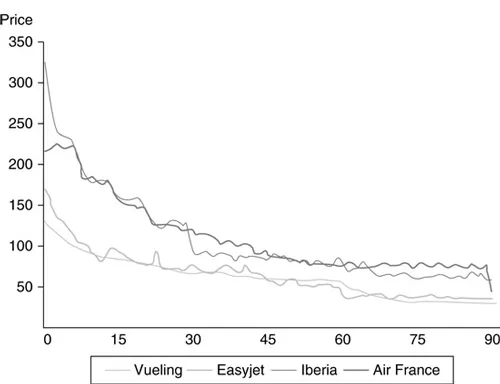

(3) Establishing dynamic pricing. Yield management techniques successfully tested by American low-cost companies after air traffic deregulation in 1978 aimed at the best price and the highest seat-occupancy rate. So different prices were given depending on how long it was before the date of the flight and what demand there was. The introduction of yield management meant that average seat-occupancy rose in comparison with that of the classic companies, to the point that the classics ended up immediately implementing dynamic pricing. Ignoring the considerable difference between the starting price of the low-cost airlines (Vueling and easyJet) and the traditional ones (Iberia and Air France), Figure 1.1 shows how a first (low) price offer was made between 90 and 60 days before the flight; then there was a second slightly higher offer, which rose as the 30-day mark approached, and then a third offer, from then until take-off, with prices that were higher, and rising. This price increase, as the flight date approached was combined with occasional special offers to hype demand. It is clear that all four lines are far from being straight.

(4) Exclusive use of the Internet as a sales channel. These companies took full advantage of the burgeoning World Wide Web as consumer confidence in electronic payment methods grew. To simplify the process, they made it the only purchase method. Through this channel they achieved a higher level of brand awareness and publicity: customer loyalty from people who wanted the lowest possible price, momentum from using a new sales channel that attracted other companies to the Net and the consequent reduction in costs.

Figure 1.1 Yield management, dynamic pricing

Source: Author’s own from sources of the companies and the QL2 Search Engine.

(5) Advertising the lowest tariffs as representative of all the company’s prices. For a good many years, this advertising policy kept the consumer convinced that all the tickets sold by low-cost companies were cheap or bargains, when in fact they were special promotions run at specific times to build up demand, and in any case represented a very small percentage of the tickets for any given journey.

(6) Alliance with the destination, which saw the establishment of the base on its territory and presence on the Low Cost Company website as the ideal promotion and sales channel.

(7) A point-to-point flight business model, run using simple processes over high-traffic routes (traffic generated by the LCC) and with selfcentrality (Bieger, Döring and Laesser, 2002). Thus, low-cost airlines created completely new routes across Europe, based around forgotten aerodromes or disused hangars re-invented as central locations for city or holiday destinations. At the base and at the landing points, they created their own streamlined structure of routes and markets.

The low-cost companies became the driving force behind the extraordinary growth in flights across Europe throughout the decade, one of the most spectacular mass-movement phenomena in history, comparable to the beginning of the sun-and-sand mass-tourism from Central and Northern Europe to the Mediterranean coast of the early 1960s. With this strategy in hand, the low-cost companies moved in to take over the market, with huge sales success, wresting market share from the grip of the established airlines. The big airlines were slow to react, and when they finally did, many months later, they emulated the majority of the low-cost airlines’ success factors, and back-pedalled into alliances and mergers, developing a transnational business model that was to become consolidated in the long term.

The success of the first low-cost companies was immediately followed by hotels, car rental companies and travel agents, selling package holidays organised by tour operators. The tourist sector took to low-cost airlines from the start, probably because it had leant that way since the beginnings of the sun-and-sand mass tourism built up by the tour operators, having always had many necessary factors in place including significant price reduction capacity, peak seasons, dynamic pricing and a facility for outsourcing. Hotels and car-rental companies implemented a high proportion of the LCC success factors.

This first period was marked by the absolute leadership of price: “low, low prices” was the message associated with the no-frills concept, with little or no mention of value; even the advertising seemed to disregard it to some extent, so a big show was made of the reduced aesthetics associated with this new low-price movement. Everything was sacrificed on the altar of price reduction, and with airlines, hotel/tourist companies in general as the front line in offering low prices through the implementation of a low-cost strategy. It was a whole low-cost philosophy.

1.2 2004 to the credit crunch and following

The period between the early days of low-cost airlines and the mid-2000s saw the emergence of low- or very low-price tactics as a strategy for breaking into the market. From 2004, the movement became associated with mass-consumption hard and soft discounts, which had existed for some decades but really gathered strength in Europe from 1990 onwards, and reached their zenith around this time. They had never achieved even 10% market share in any European country, yet between 2003 and 2006 they saw spectacular growth, going from 12% to 15.1%, while local trade could only manage 3.8% to 4.8%. These were self-service stores, with:

Their own brands

Prices between 15% and 30% lower than the reference prices

A limited number of products; between 500 and 1,000 items

High turnover

Low level of service and infrastructure on the premises

Operational efficiency

A high number of branches

They appl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Birth of the Low-Cost Phenomenon

- 2. Reinventing Your Business Model (RYBM)

- 3. Brand Marketing at a Time of Heightened Price Sensitivity

- 4. Case Studies in Innovation to Produce Lower Prices: IKEA, ING DIRECT, Mercadona and Privalia

- Epilogue: Expansion, Innovation, Price Sensitivity and Wealth

- Bibliography

- Index