- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

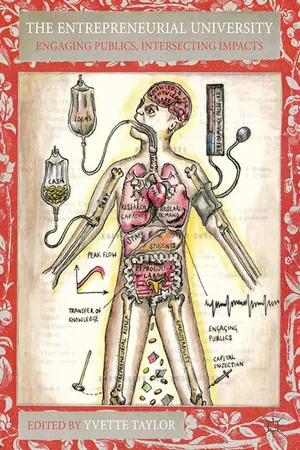

The entrepreneurial universityhas been tasked with making an impact. This collection presents professional-personal reflections on research experience and interpretative accounts of navigating fieldwork and broader publics, politics and practices of (dis)engagement primarily through a feminist, queerand gender studies lens.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Entrepreneurial University by Y. Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

(Non)Academic Subject: Occupational Activism

1

Academia Without Walls? Multiple Belongings and the Implications of Feminist and LGBT/Queer Political Engagement

Ana Cristina Santos

Introduction

Feminist and LGBT/queer researchers have variously demonstrated the situated character of all knowledge, presenting a systematic and well-substantiated critique against positivist ambitions of neutrality. In the context of increasingly fluid boundaries, shifting identities and economic precariousness in general – and for scholars in LGBT/queer studies in particular – researchers’ multiple belongings necessarily impact on the topics and methodologies used in research (Ryan-Flood and Gill, 2010; Taylor et al., 2010). Despite the increasing concern with intersectionality and the myriad impacts stemming from feminist and LGBT/queer contributions, mainstream academic praxis exercises both subjective and direct constraints upon politicised epistemologies, thereby often influencing the course and the impact of politically engaged research. Moreover, positivist practices and analyses still endure in mainstream institutions, often influencing academic curricula and criteria for granting funding.

This chapter will offer a critical analysis of disengagement within and beyond academia, doing so by examining the risks and difficulties emerging from the double-agency status of scholar–activists, that is, academics who are also actively engaged in collective action. I argue that in the post-positivist era, new and resilient (albeit discrete) walls are daily re/built, particularly in relation to issues of gender and sexuality. In so doing, a ‘hierarchy of credibility’ and of worth is reinforced, whereby engaged feminist and LGBT/queer work is often labelled as too political to be academic enough. Therefore, under the dominant power dynamics within academia, scholar-activism is invested with a twofold responsibility: to develop cutting-edge academic scholarship, observing the principles of critical emancipatory research, and to contribute to a non-hierarchical reciprocal relationship within academia and between academia and civil society. ‘Reaching out, giving back’ – as the initial call for chapters in this book suggested – encapsulates such challenge and opportunity. The challenge consists of reaching out for wider audiences, using intelligible language and arguments that resonate with people’s experiences; the opportunity emerges from the possibility of making academia more inclusive, democratic and relevant, beyond the often-massive walls behind which academic knowledge tends to remain closeted.

Shattering old walls: public sociology and the role of scholar-activism

The pervasive legacy of positivism in academia is mirrored by the ways in which sociology, rather than being proactively engaged in tackling inequality, frequently operates according to dominant ways of thinking and doing. Despite the persistence of positivist tradition in academia, questioning, contesting and subverting have been at the core of sociological intervention since the outset, thus feeding regular opposition to positivistic research methods and analysis. One relatively recent, but consistent, approach designed to tackle well-established positivistic principles is ‘public sociology’, not as a functionalist, policy-driven compulsory approach, but as a epistemological and ontological position that advances the need for politically engaged academic work.

Before plunging into the different meanings of public sociology and its related implications, it is important to note – given the thematic focus of this chapter – that despite the lively discussions and writing that public sociology has generated in recent years, what inspired this notion is not new. It can be traced to sociological literature in the 1960s, when understanding social conflict and collective action demanded more than desk-based research. More specifically, the influence of feminist and LGBT/queer writings and demands cannot be dismissed from the process through which public sociology became such an acclaimed notion. On the contrary, what could be considered an ethics of political engagement was clearly influenced by this sort of scholarship and activism, which have both been ground-breaking in advancing the notion that the personal is political and the private should be public (Harding and Norberg, 2005; Lister, 1997; Oakley, 1982; Ryan-Flood and Gill, 2010). Therefore, feminist and LGBT/queer scholars were pioneers in the process of shattering the old positivist walls of academia, including the field of sociology (Seidman, 1996; Irvine, 2003; Santos, 2013).

In his book, The Unfinished Revolution, Engel offers an example of a politically engaged study situated at the junction between academia and activism. He states that his participation in Washington’s candlelight vigil for the murder of the young gay man Matthew Shepard in October 1998 made him ascribe a new meaning to his research, as he realised that ‘an emotionally emptied account of this movement fails to do justice to the individuals who work every day so that gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people can live safer and happier lives’ (2001: 3). This event impelled Engel to write a book with a pragmatic goal: that the evolution of social theory on social movements would allow for a deeper understanding of gay and lesbian movements. He believed that, ultimately, such a task could help LGBT movements learn how to benefit from political opportunities, so that homophobia and heterosexism would finally be overturned. Engel’s stated purpose of the usefulness of his research reveals the potential for engagement between academia and activism. Furthermore, the research highlights that, rather than seeking to erase ‘where one comes from’, positionings which locate and implicate, should be self-reflexively acknowledged. And embrace it.

Engel’s politicised take on scholarly analysis is shared with many scholars throughout the world. The importance of acknowledging one’s multiple belongings, and their significance in informing theoretical understandings of the world we inhabit, draw on earlier notions of public sociology. The notion of public sociology has acquired several meanings that have quite distinct implications, both theoretical and political. One understanding of it draws on the instrumentalisation of academic knowledge in light of previously established policy measures. According to this perspective, public sociology would focus on partial data and analysis to serve interest groups, namely those which are dominant in decision-making processes. In other words, sociology becomes an engaged applied science, and this engagement would represent legitimisation through the theoretical reinforcement of the (political) establishment. The question of publics – who gets to be heard and who is silenced, which issues are left unvoiced and unseen – is a significant part of the critique against this functionalist and policy-driven understanding of public sociology (Taylor and Addison, 2011; Sousa Santos, 2002, 2004). Importantly, however, such a functionalist take on public sociology distances itself from its original meaning and purpose.

Public sociology has been presented as a theoretical approach that acknowledged the highly contingent framework of scientific production as well as science’s responsibility in liaising with other actors in order to develop reciprocal and non-hierarchic learning processes. Herbert J. Gans formulated a definition of what being a public sociologist entailed:

A public sociologist is a public intellectual who applies sociological ideas and findings to social (defined broadly) issues about which sociology (also defined broadly) has something to say. Public intellectuals comment on whatever issues show up on the public agenda; public sociologists do so only on issues to which they can apply their sociological insights and findings. They are specialist public intellectuals. (2002: 2)

Therefore, according to Gans, public sociology would be an intrinsic attribute of sociological intervention: to have something to say, to generate insightful understandings, to share (publicly relevant) findings. Drawing on Gans’s work, Michael Burawoy took the definition further, suggesting specific ways in which public sociology can add original contributions to theoretical and methodological knowledge:

The bulk of public sociology is indeed of an organic kind – sociologists working with a labor movement, neighborhood associations, communities of faith, immigrant rights groups, human rights organisations. Between the organic public sociologist and a public is a dialogue, a process of mutual education. The recognition of public sociology must extend to the organic kind which often remains invisible, private, and is often considered to be apart from our professional lives. The project of such public sociologies is to make visible the invisible, to make the private public, to validate these organic connections as part of our sociological life. (2005: 7–8)

Burawoy’s definition of public sociology seems to imply a bilateral (or even multifarious) process of exchange, ‘a dialogue’ that aims at enhancing reciprocal chances of learning. Such a process involves academia, but also the wider society (‘a public’) which is expected to be recognised by sociologists as an equally important interlocutor in this dialogue. Furthermore, Burawoy’s arguments contain an implicit call for politicised action: sociologists have the power, and the duty, to intervene in the social sphere in order to enhance visibility, participation and inclusion. As such, political engagement is not merely an unintended consequence of sociological work; it is rather a process of willing disclosure through which sociologists become engaged political actors. In other words, public sociology is not a mere ‘add-on’, something external to the sociological work itself, but a vital part of it. Accordingly, sociologists

constitute an actor in civil society and as such have a right and an obligation to participate in politics. ... The ‘pure science’ position that research must be completely insulated from politics is untenable since antipolitics is no less political than public engagement. (2004b: 1605)

In line with the previous quotes, it can be argued that sociologists should interact politically with a world in which realities of exclusion and inequality demand a pro-active role from academics, and from sociologists in particular. In accordance with this rationale, knowledge production should be concerned with audiences beyond academia, investing in outreaching initiatives that disseminate research findings in an accessible language and engaging different types of social actors during the process of knowledge production (Ackerly and True, 2010).

Arguably, sociology benefits from disclosed political engagements, and does so to the extent that sociologists are, themselves, actors in processes and facts under sociological scrutiny. What seems artificial, then, is the alleged distinction between science and politics, as if a strict boundary, however false and precarious, could secure scientific accuracy. I suggest that what is wrong in this equation is the premise of neutrality, which disregards the fundamental fact that all actors, including sociologists, are situated subjects.

To the extent that context informs people’s standpoints – from which, then, sociology is produced – it is not possible to escape knowledge which is inextricably bounded and situated. Then, the next logical step, it seems, would be to recognise one’s political standpoint and to strive for a ‘strong objectivity’, defined by Harding as ‘a commitment to acknowledge the historical character of every belief or set of beliefs’ (1991: 156). Harding underlines the inescapability of ‘historical gravity’ by saying:

Political and social interests are not ‘add-ons’ to an otherwise transcendental science that is inherently indifferent to human society; scientific beliefs, practices, institutions, histories, and problematics are constituted in and through contemporary political and social projects, and always have been. (1991: 145)

Speaking as a standpoint theorist and arguing against the ‘conventional view ... [that] politics can only obstruct and damage the production of scientific knowledge’ (2004: 1), she correctly points out that

[t]he more value-neutral a conceptual framework appears, the more likely it is to advance the hegemonous interests of dominant groups, and the less likely it is to be able to detect important actualities of social relations ... . The ‘moment of critical insight’ is one that comes only through political struggle. (2004: 6, 9)

Therefore, according to Harding, not only is neutrality impossible to achieve but, in fact, alleged neutrality adds an extra layer of strength to already hegemonic thinking to the extent that it presents itself – and the knowledge it replicates – as non-biased, hence ‘true’. Importantly, however, Harding also concurs with the idea that a holistic and inclusive understanding can only happen through critical analytical thought which stems from political engagement. As such, the dominant notion of objectivity is nothing but ‘weak objectivity’ (Harding, 1991).1 Wylie takes the argument of the usefulness of political engagement a step further, writing that ‘considerable epistemic advantage may accrue to those who approach inquiry from an interested standpoint, even a standpoint of political engagement’ (2004: 345).

Though an extended debate about standpoint theory and its critiques is beyond the scope of this chapter, the importance of political engagement within academia should not be overlooked. As Harding eloquently put it, standpoints are ‘toolboxes enabling new perspectives and new ways of seeing the world to enlarge the horizons of our explanations, understandings and yearnings for a better life’ (2004: 5). In this context, the role of those who can be described as ‘scholar–activists’ (Santos, 2012) – that is, people who are simultaneously academics and activists – becomes not only legitimate, but desirable. The possibility of a desirable role for scholar–activists within academia is clearly informed by the notion of public sociology.

By revaluing the notion of standpoint, rather than attempting to shield science from politics, scholar–activists are contributing to a significant sociological turn, one that reinvents sociology as a socially and politically relevant field of study. At least in principle, the practice of scholar-activism also highlights the importance and validity of, otherwise, rather void notions such as interdependence and intersectionality between academia and civil society. Scholar-activism opens up the possibility of rejecting the constraining ‘either, or’ rationale and, instead, reasserting the spaces ‘in-between’, embracing ambiguity and revaluing diversity from both within and outside academia. This necessarily leads up to a new ethics of research that is committed to the willing disclosure of researchers’ political engagement.

This turn presents opportunities, as well as challenges, stemming from the epistemological and ethical implications of political engagement. Before we return to these in detail, the next section examines academia’s attempt to shield itself behind what often remains unacknowledged: the resilience of disciplinary knowledge production and the competing status of different knowledge-producers.

Spotting subliminal walls in present times

In the aftermath of lively discussions around the notion of public sociology (Burawoy, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c, 2005), the idea of mutually engaged scholarship and politics gathered more interest and legitimacy. Deconstructing the ‘ivory tower’, diluting the boundaries between academics and civil society, overcoming processes of othering and of top-down learning strategies – these became important tasks for politicised academics willing to contribute to social change. And this tendency towards bridging academia and civil society finds its roots in earlier processes of theoretical and political transformation. In the aftermath of the work advanced by T.H. Marshall in the 1950s, citizenship, at least in the Western world, became a keyword, and the knowledge advanced by social sciences seemed to be strongly connected to this pro-citizens turn within academia. Sociology in particular emerged out of the need to understand collective behaviour, especially the one advanced by social movements and ot...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: The Entrepreneurial University Engaging Publics, Intersecting Impacts

- Part I (Non)Academic Subject: Occupational Activism

- Part II Mediated (Dis)Engagements and Creative Publics

- Part III Enduring Intersections, Provoking Directions

- Index