- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume explores South Korea's successful transition from an underdeveloped, authoritarian country to a modern industrialized democracy. South Korea's experience of foreign aid gives a unique perspective on how to use foreign aid for economic development as well as how to build a strong partnership between developed and developing countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The South Korean Development Experience by E. Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Development to Development Cooperation: Foreign Aid, Country Ownership, and the Developmental State in South Korea

Eun Mee Kim and Pil Ho Kim

Introduction

South Korea’s phenomenal economic development in the second half of the 20th century from one of the poorest “basket case” states to having an economy that can boast to being 13th in the world, has led to new global roles for the country. In January 2010, South Korea joined the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as its 24th member, signaling its growing role as a major donor of foreign aid. In November 2010, South Korea successfully hosted the first G20 Summit Meeting in Asia and introduced the development agenda. In November 2011, the fourth and final High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (HLF-4), hosted by the OECD and the World Bank, took place in Busan, South Korea.

In search of a new, responsible global role in the 21st century, the South Korean government has announced that it will provide foreign aid with a “South Korean Model of Development Cooperation” based upon its own “development experience” in the latter half of the 20th century. Out of this ambitious announcement come two questions: First, what were the distinct, if not unique, characteristics of South Korean development in the 20th century? Second, if there are such characteristics, how do they fit in with the global norms for development cooperation in the 21st century? The goal of this chapter is to answer these two questions by revisiting the South Korean development experience in light of today’s global norms for development cooperation. At the risk of retroactive rationalization, we would like to focus on the “country ownership” of foreign aid – or ODA (Official Development Assistance) in today’s terminology – that the South Korean “developmental state” effectively utilized in order to guide its phenomenal economic development.

There is wide consensus in the academic literature in international political economy that South Korean development in the 20th century was based on a market-guiding developmental state, to which we would like to add that it also exercised strong ownership in its negotiations with major donors of ODA. The South Korean developmental state was not only a strong state in the domestic context, but it was also a tough negotiator with foreign governments when it came to major decisions regarding its economic development. Thus, we focus here on how the developmental state negotiated its space vis-à-vis the major donors of ODA when it was a major recipient state, thereby preempting the ownership principle a few decades earlier than this principle became formulated as theory. Next, we critically examine how conditions of the global political economy, as well as domestic political situations, are different in the 21st century, which may well limit the relevance of the South Korean experience to other developing countries.

These are timely issues, since many nations with poverty have looked to countries such as South Korea for an effective alternative model for poverty reduction and development. Broadly speaking, South Korea’s development can be relevant for countries faced with the triple challenges of extreme poverty, lack of democratic governance, and fragile security. In this chapter, we will discuss a South Korean “alternative” rather than a “model.” The term “model” is based on the very problematic idea of “one-size-fits-all” – a singular type of development that does not correspond with the global norms on foreign aid and development cooperation that recognize diverse developmental contexts of recipient nations. Before getting there, however, we need first to establish a theoretical link between the concept, developmental state – which addresses “national” economic development – and the ownership principle in “international” development cooperation.

The developmental state and the ownership principle

The autonomy and capacity of the developmental state

Since Johnson (1982) coined the term “developmental state” to explain Japanese economic development that spanned the pre- and post-World War II period, this term has not only become representative of such East Asian cases as the original “Four Tigers” – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore – but has also spread as a theoretical framework to other regions such as Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and even Western Europe (Haggard 1990; Evans 1995; Robinson and White 1998; Woo-Cumings 1998; Leftwich 2000; Mkandawire 2001; Chibber 2003; Kohli 2004; Edigheji 2010). Undoubtedly, the popularity of the developmental state theory was mainly due to the phenomenal performance of the East Asian states, which formed a “flying-geese pattern” of economic development, with Japan leading the way. Moreover, in its formative period of the 1980s, research in developmental states found its natural ally in the “state-centered” approach aimed at “bringing the state back into” the social sciences (Skocpol 1985; Stubbs 2009).

The state-centered approach enriched the developmental state literature with two key concepts: state autonomy and state capacity. In return, the developmental state literature provided ample evidence of strong bureaucratic states in East Asia ruling efficiently over relatively weak civil society, private interests, and social classes, which reinforced the idea that the state plays a central role in the national political economy. Be it in formally democratic Japan or authoritarian South Korea and Taiwan, one could easily identify the locus of state autonomy as well as capacity in the well-trained civilian bureaucracy responsible for economic planning and industrial policy. Later, however, Evans (1995) revised the original formulation of the developmental state’s autonomy into “embedded autonomy” – the state bureaucracy becomes autonomous, not by detaching itself from society at large, but by further embedding itself in a “dense network of social ties” with private actors, and thereby enhancing its capacity to achieve industrial transformation.

It is clear that state autonomy and capacity are closely knit together in the predominantly domestic context of a developmental state. What if the question of development goes beyond the borders and involves international actors? Whereas Brazil’s industrialization was attributed to the “triple alliance” of multinational corporations, state elites, and local capitalists, South Korea managed to do without the significant presence of multinational capital in its dual development coalition between the state and domestic big business (Evans 1979; Kim 1997). But South Korean sovereign autonomy vis-à-vis international actors in terms of economic development was far from guaranteed; instead, it was a prize hard-earned by a South Korean leadership determined to exercise its “ownership” over a national economy that had been largely driven by foreign aid (Kharas et al. 2011; Kim 2011).

This story, as we shall see later, is more complicated than a simple assertion of sovereignty by nationalistic leadership. Without bureaucratic capacity built up from the previous decade’s foreign aid administration and the institutional structure that sustained it, the young military regime would have had much more trouble turning the economy around than it actually did during the first few years after the 1961 coup. The point is that for a successful “installation of the developmental state,” autonomy and capacity should go hand in hand (Chibber 2003). Four decades later, the equivalent of this argument in contemporary discourse on development cooperation would be the ownership principle in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005).

Global norms for development cooperation and the ownership principle

The OECD/DAC provides policy guidelines for ODA, and considers capacity building as a priority of national development. Capacity development has been regarded as a key factor to promoting leadership and ownership of a partner country in the process of development (OECD 2009c). In order to achieve capacity development, six priority areas were identified:

(1)country systems’ capacity,

(2)enabling environment for capacity development,

(3)capacity development in fragile situations,

(4)integrating capacity into sector/thematic strategies,

(5)role of civil society and the private sector in capacity development, and

(6)relevance, quality, and choice of capacity development support (OECD 2009b; Pearson 2010).

What distinguishes the OECD/DAC guidelines from developmental state practices in the 20th century is the emphasis on political as well as economic development. In terms of political development, the OECD/DAC highlights good governance and the participation of civil society organizations (OECD 1995, 2009b). The OECD/DAC encourages women’s empowerment and the involvement of the private sector in the national development process, since the active involvement of women is critical for social, political and economic development (OECD 1999, 2009b, 2010).

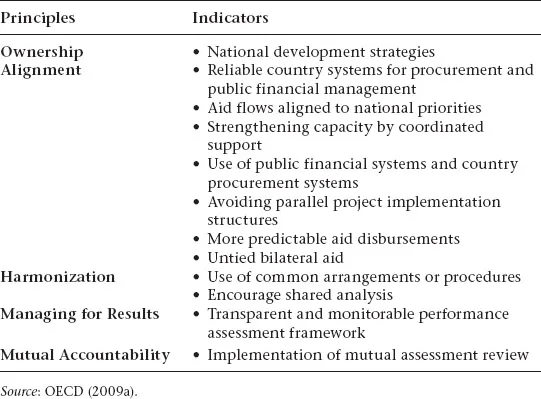

The Paris Declaration was a result of a major international effort to improve aid effectiveness, with more than one hundred donors and partner countries signing on to commit to major reforms in aid delivery. As summarized in Table 1.1, they agreed on five principles: ownership, alignment, harmonization, managing aid for results, and mutual accountability. They also came up with twelve indicators to measure aid effectiveness.

Quite tellingly, the ownership principle is located at the top of the aid effectiveness pyramid (OECD 2009a; Fritz and Menocal 2007: 543), suggesting that ownership is the most important of all five principles. This impression is reinforced by the following Accra Agenda for Action (2008), in which “Strengthening Country Ownership over Development” was again at the top of the list of priorities (OECD 2009a). In fact, the ownership issue was first brought up by the IMF/World Bank in the late 1990s, featuring in the Comprehensive Development Framework and the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (Wolfensohn and Fischer 2000; Pender 2001; Cammack 2004). By elevating it to the top principle of ODA, the OECD/DAC opened up a floodgate of discussion about how to define and/or assess country ownership. The Paris Declaration contributed further to the discussion on ownership by specifying its actual indicator: national development strategies.

Eberlei (2001) defines ownership in terms of popular participation, in which the majority of the partner country’s population or its representatives take part in the formation and/or implementation of a national development strategy. This marks a critical departure from the implicit assumption of the IMF/World Bank that the partner country’s officials are to carry out development policies for their national interest (IMF 2001: 6). The potential conflicts of interest between the state elite and the popular mass is a question at the heart of the aid effectiveness discourse, not to mention democratic legitimacy and good governance. Then, again, the East Asian experiences in the last century, as exemplified by the likes of South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore, attest to the compatibility of authoritarianism and developmental success.

Table 1.1 Five principles and twelve indicators of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness

A resolution may be found in the political aspect of ownership, rather than in the abstract definition of the term. Whether it is over an object or a process, ownership does not necessarily mean complete authority, even though it refers to the responsibility to take final decisions; ultimately, ownership is subject to social control in the broad sense (Cramer et al. 2006). In practice, ownership involves a wide range of political factors:

(1)a sense of national purpose,

(2)intellectual conviction of key policy-makers,

(3)support from the top political leadership, and

(4)visible efforts of consensus-building among various constituencies (Johnson and Watsy 1993; Brautigam 2000; Nissanke 2010; Booth 2011).

Whether or not the ownership principle is intended to bolster state autonomy of the recipient country vis-à-vis international donors is questionable from the donors’ perspective. This is not to even mention those critics who are extremely skeptical about the IMF/World Bank-defined “ownership” and its political–economic ramifications in the developing world (Harrison 2001; Pender 2001; Cammack 2004). Fritz and Menocal admit that the “goal of promoting country ownership is far from straightforward,” and yet the “expectation is that national development strategies will provide a strategic policy framework oriented towards results that donors can support” (2007: 545). Simply put, donors are likely to respect recipients’ autonomy as long as they see desirable results. If the ownership principle boils down to the establishment of a successful development strategy in practical terms, then it looks like an important endorsement of the South Korean development experience, especially when South Korea made a transition from an aid-dependent country in the 1950s to a developmental state with a clear-cut development strategy in the 1960s. In so doing, the South Korean developmental state ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: The South Korean Development Experience

- 1 From Development to Development Cooperation: Foreign Aid, Country Ownership, and the Developmental State in South Korea

- 2 The Effect of Aid Allocation: An Econometric Analysis of Grant Aid and Concessional Loans to South Korea, 1953–1978

- 3 Coordination and Capacity-Building in U.S. Aid to South Korea, 1945–1975

- 4 Aid Effectiveness and Fragmentation: Changes in Global Aid Architecture and South Korea as an Emerging Donor

- 5 The Capability Enhancing Developmental State: Concepts and National Trajectories

- 6 South Korea’s Development Experience as an Aid Recipient: Lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa

- 7 The Politicization of Humanitarian Assistance: Aid and Security on the Korean Peninsula

- Conclusion: Beyond Aid

- Index