- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Secrets, Lies and Children's Fiction

About this book

Many children learn from a young age to tell the truth. They also learn that some lies are necessary in order to survive in a world that paradoxically values truth-telling, but practises deception. This book examines this paradox by considering how deception is often a necessary means of survival for individuals, families, governments, and animals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Secrets, Lies and Children's Fiction by K. Mallan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Truth, Lies and Survival

1

Unveiling the Truth

As an item of clothing, the veil is inscribed with various historical and cultural meanings. Muslim women and girls who wear ‘veils’ or headscarves1 in accordance with hijab follow the dictates of their religion regarding modesty in dress and behaviour. From a Western perspective with its economic investment in fashion, the veil would seem to inhibit emulous display among women. Veils cover the hair, ears and throat or, in the case of the burqa, the entire body, with only a grille or netting over the eyes to allow the wearer to see. The concealment of the woman’s body is to ensure sexual modesty.2 In another religious context, when a woman ‘takes the veil’ she becomes ‘a bride of Christ’ giving up all worldly goods, taking vows of chastity and poverty, and often living within a religious order. A very different kind of veil comes into play with the dance of the seven veils by Salome, a performance that has been copied by other femmes fatales in many films. This dance of seduction is a striptease, a spectacle which Barthes (1957: 84) notes is ‘based on fear’, or ‘the pretence of fear’, ‘a delicious terror’ with the veils, or other adornments (furs, fans, gloves, feathers, fishnet stockings), tantalising and evoking the idea of nakedness and sexual fantasy. We have a collection of veil wearers – striptease performers, dancers of the seven veils, femmes fatales, nuns, Muslim women and girls (and there are more) – and while in each case the veil serves a different purpose, the eye of the beholder will respond sometimes with fear, sometimes with excitement, sometimes with shock or surprise, sometimes with respect. These varied instances of the veil and of veiling assign cultural, material, spatial, communicative and religious meanings (El Guindi 1999: 6). The veil, therefore, is a material object as well as a trope that evokes multiple interpretations. It hides a mystery, and signifies a host of oppositional binaries: difference or recognition, exotic or traditional, freedom or oppression. Thus, a seemingly innocent piece of clothing is capable of provoking diverse reactions. More significant for this chapter is how the veil, as both a noun and a verb, can reveal or conceal truth.

To consider the implications of the veil, of veiling and unveiling, this chapter narrows the possibilities that beckon by first considering the veil in memoir and fiction about Muslim girls, namely, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (2003) and Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return (2004) by Marjane Satrapi, and Does My Head Look Big in This? (2005) by Randa Abdel-Fattah. In the second part of the chapter, my attention turns to ‘un/veiling’ in a metaphorical sense, examining how both the clothed (animal) body and the naked (human) body can serve as a metonym for truth. The discussion throughout this chapter complicates the rather simplistic idea of concealment as deception, and unveiling as truth, by taking into account how subjects transform themselves in their quest to find the truth.

Seeing through the veil

If all fiction veils a nakedness, as Derrida suggests, then one of the most potentially exposing forms of writing would be the story of the self, or the life narrative. However, as I mention in the Introduction to this book, it is doubtful that any text is ever ‘naked’ as the metaphoric nature of language always offers a ‘veil of words’ (Krajewski 1992: 124). Therefore, to consider a genre such as life writing as an example of the ‘author stripped bare’ is naïve, but, nevertheless, life narratives offer spaces of exposure within the inevitable covering of words and their metaphorical associations. Life narratives are part of a larger body of literature that comprises autobiography, diary, memoir, confessional writing and literature of trauma. Whitlock suggests that ‘contemporary life narrative touches the secret life of us; indeed, it is part of how we come to imagine “us” ’ (2007: 10). Life writing carries a burden of truthfulness, if not some truths, and a claim to authenticity. But like literature, these stories mediate accounts of personal life experiences into the public domain, often bringing with them ‘a socio-cultural history’, and always a temporality (Douglas 2006: 44). In children’s literature, life narratives often take the form of fictionalised autobiographies or diaries. Chapter 2 and 6 examine fictional/ised diaries but my interest here is in the graphic memoirs Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (2003) and its sequel Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return (2004). Whitlock notes that Satrapi uses the graphic memoir as an alternative form of autobiography, conveying the story of her childhood and young adulthood (2007: 188).

In Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, Marjane Satrapi tells a story of her life in Tehran from ages six to 14, a period which sees the overthrow of the Shah’s regime, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the Islamic theocracy that followed. It also tells of the effects of war with Iraq. In Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return she tells of her life as an adolescent in Vienna and her return to Iran as a young woman. My purpose is to explore how these narratives of survival and adaptive behaviour unveil the author’s life experiences, weaving together fragments of truths drawn from autobiography, family biography, history and culture. The discussion considers how these fragments come to express a truth of lived experience, as well as construct extra-textual truths. The third text, Does My Head Look Big in This? by Randa Abdel-Fattah (2005), is not a life narrative, but a fiction. However, the story emerges from the author’s political and cultural beliefs as an Australian Muslim woman.3

In all these texts, the narratives creatively reconstruct and redescribe the veiled experience. Paul Ricoeur (1985) uses the term ‘redescription’ to explain how narrative (or specifically metaphor) cannot directly reference the world outside the text but it can permit us to see it in a new way. For Ricoeur, art cannot simply imitate life, in the Aristotelian sense of mimesis, but it can borrow from life and transform it. In writing about a life, the representation may appear as mimesis, mirroring the author’s real life. Ricoeur considers the concept of poiesis in the Platonic-Aristotelian interpretation as a form of mimesis to be not so much about the production – the finished ‘poem’ – but the act of poetic creation. This concept of poiesis as artistic production is useful in considering how the idea of truthful revelation, which memoir (or life narrative) seeks to disclose, is always framed by notions of reliability, authority and authenticity, which readers come to expect when they encounter a text that asserts its autobiographical status: the cover blurb of Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood describes Satrapi’s book as a ‘wise, funny and heartbreaking memoir’. However, to consider life writing to be more ‘truthful’ than fiction, ignores the function of poiesis as an artistic process with the ability to both reveal and transform: ‘poiesis reveals structures which would have remained unrecognized without art, and that it transforms life, elevating it to another level’ (Ricoeur, cited in Wood 1991: 182, emphasis original). Furthermore, life writing and fictionalised accounts that interweave ‘fragments of the real’ intersect at a point which draws attention to how creative production can assist readers to understand human actions and socio-political history by reconstructing them in the world of the text: a world which is arguably an imaginary universe, but one that reveals and transforms as it symbolically renders the past under the sign of memory or redescription. The Persepolis stories are not mimesis, copies of Satrapi’s life, but poiesis: a creation and a construction of her past. Satrapi reconstructs and creatively redescribes the thoughts and experiences of her childhood and youth through words and comic-strip illustration. Whitlock sees the comic format performing a dual function: on the one hand, the illustrations are ‘elemental’, evoking a naïve, childlike quality, but they are also sophisticated, which forces readers ‘to pause and speculate about the extraordinary connotative force of cartoon drawing, which both amplifies and simplifies’ (2007: 188). As the dominant mode of storytelling in this text, the illustrations convey the physical, emotional and political transformations that the represented subject (Satrapi) undergoes as she not only moves through childhood to adulthood but also moves away from her home and her life in Iran.

Self-representation is the element that defines all forms of life writing. How one reveals or conceals details about oneself is a necessary strategy, or deception. Self-representation also requires an account of others, and how we actively assimilate and transform ourselves and others contributes to our subjectivity and intersubjective relations. Foucault’s (1978, 1980) accounts of social and historical existence and the often perilous conflict or dialogue of forces one encounters provide an important lens for my reading of the Persepolis texts. These texts illustrate how ‘Satrapi’ or her narrated self ‘Marji’ is affected and transformed by external forces. However, she is not simply passive, yielding to outside influences. Rather, she is a subject with agency who is capable of interpreting and acting upon the world. Satrapi draws on a range of techniques in her poetic reconstruction of a life that once was. Both Persepolis texts use humour (irony and satire), exaggeration and caricature to mediate harsh realities providing avenues for comic relief.

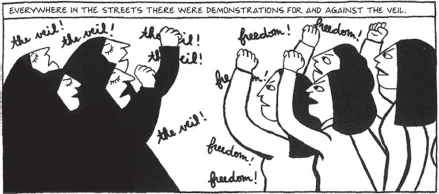

Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood begins in 1979 in Iran at the time of what was to be known as the ‘Islamic Revolution’, and the fundamentalist Islamic regime that followed. By 1980 it had become obligatory for girls to wear the veil. Writing in the first person, the narrator, Marji, explains how the significance of the veil eluded her and other children: ‘we didn’t really like to wear the veil, especially since we didn’t understand why we had to’ (2003: 3). In describing girls’ attitudes to the veil the text uses an idiomatic discourse with accompanying subversive illustrated incidents within the one scene showing the children using the veil as a toy thing, pretending that it is a skipping rope (‘Give me my veil back!’), a rein for a horse (‘Giddyap!’), a disguise (‘Ooh! I’m the monster of darkness’), mocking the ruling regime (‘Execution in the name of freedom’) and complaining (‘It’s too hot out’). This scene carries a generational significance that goes beyond cultural limits as the young girls place play above compliance. Their reactions also separate the world of adults with their ideological allegiances from the world of children who live within that world but create a carnivalesque space that does not permit authoritarianism and seriousness (Stephens 1992: 121). The sign–referent relationship is playfully disrupted, showing the relativity of the ‘truths’ and ideologies inscribed by the dominant discourse of the Islamic rule with the physical reality and ‘truths’ of the children. The tensions and differences of ideological viewpoints are carried through to the ways the Iranian women represented in the text see the veil as either an object of oppression or a sign of religious observance: ‘Everywhere in the streets there were demonstrations for and against the veil’ with the illustration showing women dressed in chadors chanting ‘The veil, the veil’, and women in modern dress countering with ‘Freedom! Freedom!’ This internal polarity is one that is familiar in the extra-literary world, especially with respect to contrasting ideological discourses (the West and Islam) to veiling. As the ideological divide between fundamentalist and modernist Islam widens, clothing becomes a complex signifier within the cultural discourses of beliefs (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Illustration from Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood by Marjane Satrapi

Words and images contrast fundamentalist and modern dress, emphasising the ideological imperative and minor reactionary stances:

In no time, the way people dressed became an ideological sign. There were two kinds of women. The fundamentalist woman. The modern woman. You showed your opposition to the regime by letting a few strands of hair show. (2003: 75)

Iranian men are contrasted as ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘progressive’, and as a mark of resistance a ‘progressive’ man is depicted as having shaved, with the comment that ‘Islam is more or less against shaving’ (75). In addition to these small acts of rebellion, Marji reveals that the oppressive regime provokes other deceptions as people attempt to avoid being exposed as being not a true Muslim. This attempt to deceive is conveyed through her parents’ sighting of their neighbours as they walk through the streets dressed in fundamentalist dress:

| [Mother]: | ‘Look at her! Last year she was wearing a miniskirt, showing off her beefy thighs to the whole neighbourhood. And now Madame is wearing a chador. It suits her better, I guess.’ | |

| [Father]: | ‘As for her fundamentalist husband who drank himself into a stupor every night, now he uses mouthwash every time he utters the word “alcohol”.’ (75) |

Ironically, while the parents scorn what they see as the couple’s hyprocrisy and deceit, Marji’s mother perpetuates a similar hypocrisy when she tells Marji that she must lie: ‘If anyone ever asks you what you do during the day, say you pray, you understand?’ Marji finds lying comes easily as she competes with other children in a lying contest of sorts. When one of her friends piously claims: ‘I pray five times a day,’ Marji replies ‘Me? Ten or eleven times … sometimes twelve’ (75). It would seem that Marji and her mother regard lying for a good reason as different from other forms of deception, such as those in which her neighbours engage.

Lying is a form of concealment (veiling), a concealment or veiling of truth. While the traditional moral distinction separates lying and concealment, this text shows how the line of demarcation is often blurred. This blurring is most obvious in public and private spaces. In public, Marji, her mother and grandmother cover their heads with scarves, and the older women wear modest black dresses. Their public displays of truthful allegiance to the law conceal their opposition, which they are not free to display openly. However, at times, Marji openly flaunts her anarchic spirit, creating her own personal dress style by wearing a new denim jacket with a Michael Jackson badge, jeans and a new pair of Nikes in public. She also trades in the black market to pay for two music tapes by Western pop stars. However, these visible signs of rebellion and freedom almost cause her to be taken to ‘HQ’ when two women, ‘guardians of the revolution’, attempt to arrest her for being improperly veiled. Marjane narrowly avoids being arrested by telling a pack of lies:

‘Ma’am my mother’s dead. My stepmother is really cruel and if I don’t go home right away, she’ll kill me […] She’ll burn me with the clothes iron. She’ll make my father put me in an orphanage.’ (134: emphasis original)

Marji’s necessary lying for survival illustrates how the binarism of truth and falsehood is far from uncomplicated, especially when individual freedom is at stake. Truth-telling is not elevated beyond other rhetorical accounts as it becomes part of her storytelling repertoire and serves a purpose that lies outside a moral or ethical dimension. The contradictory self-representations and dress concealment – as a veiled girl, a revolutionary activist, a subject of abuse – demonstrate the complex relations between concealment and lies, between veiling and unveiling.

The interplay that the veil evokes between sight and body draws attention to layers of concealment. By modestly concealing parts of the body, the veil (or burqa in concealing the full body) effectively replaces individual differentiation by cultural differentiation. In wearing the veil, chador or burqa Muslim women appear to erase their individuality: the implication is that agency is also erased, and culture is symbolically rendered. We will return to this point about erasure of individuality in the discussion of Persepolis 2, but for now my point is to highlight the hierarchy of dominance and submission, as well as homogeneity, that the veil evokes when viewed through a Western lens. Whitlock puts it this way: ‘The image of the veiled woman in particular is a powerful trope of the passive “third world” subject, and it sustains the discursive self-presentation of Western women as a [sic] secular, liberated, and individual agents’ (2007: 49). Marji disrupts this projected image of passivity. After the death of her friend, she becomes rebellious, wearing jewellery and jeans with the mandatory long black dress and headscarf to school. After she argues with and assaults her Principal, Marji is expelled. Her aunt manages to get her accepted into another school, but Marji argues with the religion teacher, accusing her of telling lies about the Islamic Republic. After this second act of rebellion, her parents decide it would be safer to send her to Austria to live with their friends, and enroll her in a French school. They fear that Marji (now 14) could be executed if she stays in Tehran and continues to be dissident.

Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return takes up the story on Marji’s arrival in Vienna. It marks a transitional period during which Marji takes on a more serious self-transformation than her former more playful anarchic gestures. It is also a time when she encounters the dilemma regarding truth and deception: both are necessary for survival. The seriousness of the strictures and controls that characterise life in Iran is given clarity when her mother’s friend Zozo and her daughter Shirin meet her at the airport. The initial conversation between Marji and Shirin opens up the ideological divide. Marji expresses to Shirin her relief and excitement about not having to wear the veil to school or ‘to beat myself every day for the war martyrs’ (2004: 2). However, Shirin fails to respond to Marji’s experience and instead boasts about her ‘really fashionable’ earmuffs, her raspberry, strawberry and blackberry-scented pens, and her ‘pearly pink lipstick’. Marji’s unspoken thoughts about her friend’s conversation condemn her as ‘a traitor’: ‘While people were dying in our country, she was talking to me about trivial things’ (2). Her time with the family is short-lived as Zozo takes her to a boarding house run by nuns. There is an irony in that escaping one form of religious dogmatism she finds herself living a cloistered existence with nuns. She soon is forced to lea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: The Burden of Truth

- Part I Truth, Lies and Survival

- Part II Secrets and Secrecy

- Part III Tangled Webs

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index