eBook - ePub

The Gold Cartel

Government Intervention on Gold, the Mega Bubble in Paper, and What This Means for Your Future

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Gold Cartel

Government Intervention on Gold, the Mega Bubble in Paper, and What This Means for Your Future

About this book

The Gold Cartel is an insightful and thought-provoking analysis of the world market for gold, how it works, and what influences gold price. But it also lends insight into something more disturbing – the organized intervention in the gold markets by Central Banks.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Gold Cartel by D. Speck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Finanza d'impresa. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Why Gold?

For hundreds of years gold and silver were synonymous with the term ‘money’. Most of the time payments were made directly with precious metals – for instance, with coins containing silver. However, bank notes backed by gold were often widely used as well. This was, for instance, the case in the ‘gold standard’, in which payment was not effected with physical gold, but the monetary unit (such as the ‘dollar’) was defined by a fixed weight of gold, and could be redeemed in gold on demand. It was completely outside the realm of the imaginable that it would ever be possible to pay with ‘unredeemable paper money’, and, historically, there were only very few temporally and locally limited episodes in which money was not backed by a commodity. Today, since the 1970s to be precise, one pays all over the world with money that is based on claims denominated in an abstract unit. It doesn’t convey any rights, except the right to exchange it for other claims of the same type.

These ‘dollars’, ‘yen’ or ‘euro’ can only function as money because the process of their creation is based on regulations designed to limit their issuance. Historically, this system has developed because monetary systems based on gold or silver have drawbacks. The use of precious metals as money was thus frequently criticised, and they were labelled as ‘barbaric relics’ or ‘useless metal’. Sayings like ‘One cannot eat gold’ are supposed to connote its alleged uselessness.

The drawbacks begin already with the production process, as gold has to be dug out of the earth with great effort. Sometimes the environment is polluted to an alarming extent in the process. The distribution of gold supplies is, moreover, regionally quite unequal, due to geographical and historical reasons. Furthermore, the supply is limited, so that the alleged ‘needs’ of a growing economy – or those of a government budget getting out of hand? – cannot be adequately served (whereby it is precisely this aspect that is seen as a benefit by supporters of gold).

Today, gold is no longer a means of payment. It no longer plays a role in large business transactions, in foreign trade or even in transactions between governments. It is, however, still held as a store of value. Private individuals usually hold it in the form of coins or bars (in some regions also in the form of jewellery, provided it is not trading at a large premium to its bullion value). A sizable amount of gold is also stored by the central banks, approximately 31,000 tons according to official statements. That is a multiple of the annual consumption of the metal.

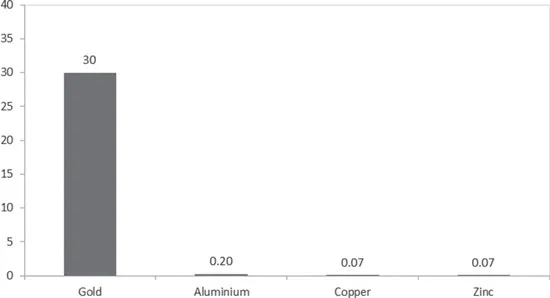

The foregoing points to an important difference to other commodities, for only in silver is this store of value function otherwise found to a noteworthy extent. It is estimated that up to today approximately 170,000 tons of gold have been mined1 and that most of it still exists in accessible form. By contrast, annual mine production amounts to approximately 2,800 tons at the time of writing, with annual consumption (industrial demand, jewellery fabrication, dentistry) amounting to perhaps 2,400 tons. Thus, the total supply of gold mined to date amounts to about 70 times the amount consumed annually. That is an extraordinarily high ratio of stocks to flows. While inventories of other commodities usually last only for months, one could stop gold production for many years and still be able to satisfy consumption demand. Of the two most important monetary functions, gold has, after all, only lost its usefulness as a medium of exchange; it has retained its function as a store of value. Figure 1.1 shows the ratio of inventories to annual production of various metals. Even though the values are only estimates, are highly variable depending on the business cycle and partly depend on definitions (is jewellery part of the stock, or is it part of what has been consumed?), they nevertheless make the extraordinary role of gold compared to other commodities plain. The chart is meant to clarify this state of affairs (only half of all the gold ever mined is assumed to be part of the available stock).

Gold is, however, also different from other investment assets. One can store value in assets like stocks or real estate as well. In contrast to gold, however, these are less liquid, often not long-lived and exposed to special risks – for instance, entrepreneurial risks. There are also differences between gold and financial capital – that is to say, credit claims, bonds and credit money. As our money is no longer backed by a commodity, it depends in the final analysis on a debtor’s ability to perform. Even though the central banking system ensures that no one has to fear that his money will become worthless in the event that a specific bank draft is not honoured, this dependence is still a given – it has merely been transferred to governments. If the state no longer can or wants to fulfil its duties in this regard, money can become worthless at a stroke (which has happened time and again in the past).

Figure 1.1 Metals: ratio of worldwide stocks to production

The supply of gold can, furthermore, only be increased with great effort, namely by mining. This differentiates it from financial capital based on credit claims, which can be created on the macro-economic level by simply incurring additional debt. This procedure fosters the threat of inflation, whereby the monetary unit, the currency, loses value. By contrast to paper money, gold therefore depends neither on the volition nor capacity of a debtor, nor can it be inflated away. That makes gold unique, it makes it the ultimate store of value – and it also makes it the object of monetary and central bank policy.

Gold is a transnational money, independent of governments. It is also independent of a society’s ability to maintain the purchasing power of money. It retains its real value through periods of inflation. Its value doesn’t disappear even in the event that entire nations or their currencies collapse. Gold from antiquity is still worth something today, most of the national currencies that circulated only a century ago aren’t. As a money transcending states, gold is in direct competition with the money which today’s central banks are in charge of. When the gold price rises, investors and savers usually conclude that paper currencies are weak, that an inflation threat looms, or they fear even worse things, such as a total loss of their savings due to a banking system collapse.

Conversely, confidence is bolstered when the gold price doesn’t rise. Inflation expectations are reduced when the best-known indicator of currency devaluation emits no warning signals. However, in times of tension and crisis in the financial markets, a flat gold price also has a calming effect: then it indicates that there is, after all, no sufficient reason yet to move one’s funds into the ultimate safe haven. The crisis appears not to be serious. It is therefore conceivably in the interest of central banks that the gold price doesn’t rise, or at least doesn’t rise in uncontrollable fashion. They would have enough gold at their disposal to brake its ascent, as a multiple of annual demand is stored in their vaults. But have central banks actively arranged for the gold price not to rise in times of crisis?

Chapter 2

The Crises of the 1990s

The financial crisis of 2008 and the euro crisis are undoubtedly among the most worrisome crises of the past few decades. There were, however, also crises before these, even though their effects in most cases remained regionally contained (while still creating enormous economic problems in the regions concerned). In September 1992, the crisis of the British pound made headlines. The pound was pegged to the other European currencies through the European Monetary System (EMS). However, this led to an overvaluation of the pound relative to the strength of the UK economy. Politicians and central bankers refused to acknowledge this – at least, they didn’t take any actions as a consequence (in the background there were in addition tensions in the EMS as a result of Germany’s reunification and the pending European currency union). However, a number of fund managers, among them George Soros, recognised the pound’s overvaluation and proceeded to bet against it to the tune of billions. They sold the pound short and eventually forced the British to abandon the defence of their currency. The pound fell and the hedge funds made big profits. Subsequently, they were accused to have been responsible for the crisis. However, after the devaluation the funds had to buy back exactly the same amount of pounds they had previously sold short. If the funds had been responsible for the crisis, then the pound would have risen back to its initial value as a result of their short covering. However, it didn’t. The funds, therefore, merely provided the trigger for the pound’s decline. The real reason was put in place beforehand, in the course of pegging the exchange rate. The pound was overvalued relative to the performance of the UK economy.

‘The man who broke the Bank of England’, as Soros was later called, could make billions in profits because he recognized a mispricing that was originally created by politicians. Above all, he showed politicians what the limits of their power were. Basic economic laws such as that of supply and demand cannot be abolished by decree. However, not all politicians drew the conclusion to henceforth act within the framework of these laws. It appears rather that the EMS crisis has given rise to the notion that it would be better to keep market interventions secret. If speculators like Soros don’t notice them, they also cannot act against them. Interventions might then be successful for longer. There are two more reasons to discuss the EMS crisis at this juncture: first, as we will see further below, it happened only ten months before the interventions in the gold market began. One must therefore assume that politicians and central bankers were under the sway of the EMS crisis. In any case, they decided to execute interventions in the gold market as inconspicuously as possible. Second, Soros is of importance as he reportedly was active in the gold market as well.

In December 1994 another currency crisis followed. It is often referred to as the ‘Tequila Crisis’. The Mexican peso was pegged to the US dollar and, as was the case with the UK and the pound, it was overvalued relative to the economy’s fundamentals. In addition, there was a lack of political stability. The peso came under pressure and had to be devalued. An economic crisis followed on the heels of the currency crisis. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which regarded this crisis as something new and called it ‘the first financial crisis of the 21st century’, helped out with billions.

Funds also came from the USA. These were provided by the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). The ESF, which is administered by the government, was founded in 1934, specifically to stabilise the US dollar and the foreign exchange markets. It acts fairly autonomously and most of the time covertly. However, in the course of the peso crisis it made headlines, as it was used to circumvent Congress, which had refused to provide aid to Mexico. Many US politicians didn’t regard support of other countries as a function of a US stabilisation fund.2 The ESF is of importance with regard to gold policy, as a number of observers suspect that it is an agent in gold market interventions. It is probably the agency most likely to possess the legal authority for interventions in the foreign exchange and gold markets. More on this later.

More crises exhibiting comparable patterns followed: in 1997 the Asian crisis in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, and in 1998 the Russian crisis. In each case the currencies of soft currency countries with high interest rates were pegged to a harder currency with lower interest rates. Such a pegged exchange rate leads to investment by foreigners, who believe their investments to be safe from devaluation. It also furthers the assumption of debt denominated in foreign currency by domestic debtors, as they can pay lower interest rates than previously. Both activities lead to an economic boom that is, to a large extent, driven by disproportionate credit growth. It is accompanied by a large current account deficit, an excess of imports of goods and services. These are financed with debt as well. This means that such countries consume more than they produce. It should actually be clear that such arrangements cannot last forever. In the wake of such excesses there are regularly crises forcing the economy to adapt to reality, often coupled with considerable slumps in economic activity.

In spite of that, politicians time and again adopt such currency pegs. Europe’s politicians have done the same. In spite of being sufficiently forewarned by these previous examples, they have also pegged weak currencies to strong ones with the introduction of the euro (with the only difference that the common currency has made a cleansing separation more difficult). The pegging of weak currencies to a strong currency is an important backdrop of the euro crisis that has been in train since the end of 2009. Such crises due to currency pegs are usually preceded by many years of enormous capital misallocations due to too low interest rates, without which the subsequent crisis could not have developed. We will examine the market trend of the gold price during the 2008 crisis and the euro crisis in more detail later. However, does the behaviour of the gold price during crises categorically hint at interventions in the gold market?

Chapter 3

The Strange Behaviour of Gold during Crises

To begin with: gold is not a good investment. Over many decades its price remains the same, while real estate, bonds and stocks yield income or rise in price. Even in times of moderate inflation, contrary to conventional wisdom, gold often does not protect against losses in real terms. It is quite different when there are substantial risks to monetary stability. That is when gold’s safe haven function comes to the fore, as it is neither dependent on a promise to pay, nor possible to inflate away. Gold, therefore, provides protection in financial crises harbouring rising default risks and when money is debased markedly. This has also been examined statistically in the context of past events.3

As soon as people fear for the safety and value of their investments, they flee into safe havens. In panic, they sell everything that might decline in price or lose its value entirely and invest their money in what they consider safe. We now want, first, to examine how gold behaved in the course of the Russian crisis in 1998. This crisis was one of the last major crises prior to that of 2008. One of its effects was that investors fled from the debt of not overly creditworthy borrowers. As a result of this, the US hedge fund ‘Long-Term Capital Management’ (LTCM) got into trouble, as it had engaged in highly leveraged bets on interest rate convergence. The threat of a collapse of the financial system loomed. The American central bank, the Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) organised what was at the time a unique rescue in order to avert a chain reaction.4

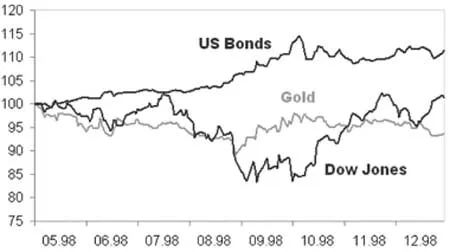

Between mid-July and the end of September 1998 stocks in the USA fell by approximately 20 per cent. During the same period, treasury bonds rose massively, as they were regarded as a safe haven. And what happened to the gold price? Overall, it barely moved; it even fell intermittently! It was as though gold were not a safe investment, but rather just as unsafe as the debt of a dubious borrower. The chart depicted in Figure 3.1 shows the performance of an ounce of gold in US dollar terms, of an investment in ten-year treasury notes and of the US stock market, represented by the Dow Jones Industrial Average during the crisis.

Figure 3.1 Gold, US treasury notes and the DJIA 1998 (indexed)

It is striking that gold did not benefit from the severe crisis, but, on the contrary, fell hand in hand with the stock market. Of course, gold had not become obsolete as a ‘safe haven’, nor should normal market phenomena like profit-taking have occurred. Why should these occur precisely at a moment when the markets were hankering for safety? One can, of course, not entirely rule out customary market-related reasons for price declines in individual cases, as sometimes, during financial crises, liquidity is needed at any price and everything is sold, including gold. That is, however, quite rare. Alternatively, the question arises whether targeted gold sales initiated by central banks were supposed to suggest calm to the markets. The crisis would be mitigated in this way; investors would be prevented from panicking even more.

In order to better estimate the price behaviour of gold in crisis situations, we now want to look at a multitude of financial crises at once, instead of only individual examples. By creating an average, we can examine the typical trend in crises and, as the case may be, detect if there are any anomalies. Financial market crises are, howeve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Why Gold?

- 2. The Crises of the 1990s

- 3. The Strange Behaviour of Gold during Crises

- 4. The Strange Intraday Behaviour of Gold

- 5. The First Statistical Studies

- 6. Statistical Proof and Dating of Gold Interventions

- 7. Intraday Movements of the Gold Price 1986–2012

- 8. Gold is Different

- 9. Means of Gold Market Intervention I: Sales

- 10. Means of Gold Intervention II: Gold Lending

- 11. The Gold Carry Trade

- 12. Coordination of Private Banks and Central Banks

- 13. Giving the Game Away: Central Bankers are Human Beings Too

- 14. The Books are Silent

- 15. The Miraculous Gold Multiplication

- 16. How Much Gold is on Loan Worldwide?

- 17. Means of Gold Intervention III: Intervention through the Futures Market

- 18. The Gold Pool and Other Gold Market Interventions before 1993

- 19. 5 August 1993, 8.27 a.m. EST: The Beginning of Systematic Gold Market Interventions

- 20. The Decisive Fed Meeting

- 21. Greenspan Ponders Gold Market Interventions

- 22. Phases of Gold Price Suppression

- 23. Shock and Awe

- 24. The Financial Market Crisis of 2008 and the Euro Crisis of 2011

- 25. Strong Dollar and Weak Mining Stocks

- 26. Interventions in the Silver Market

- 27. Swapped Bundesbank Gold and Other Mysteries

- 28. Who Intervenes?

- 29. The Mystery of 18 May 2001, 12.31

- 30. The Effects of Gold Price Suppression

- 31. The Wonderful World of Bubbles

- 32. Have Many Mini-Bubbles Created a Mega-Bubble?

- 33. Money or Credit?

- 34. Possible Scenarios for the Future

- 35. Back to Gold

- Appendices

- Notes

- Index