- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A challenging reappraisal of the history of antipsychotics, revealing how they were transformed from neurological poisons into magical cures, their benefits exaggerated and their toxic effects minimized or ignored.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bitterest Pills by J. Moncrieff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychiatry & Mental Health. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Cure or Curse: What Are Antipsychotics?

Antipsychotic drugs, otherwise known as neuroleptics and sometimes major tranquillisers, were introduced into psychiatry in the 1950s. Many people believe these drugs were the first really effective treatment for the severely mentally ill, and they have been referred to as ‘miracle’ or ‘wonder’ drugs that were said to represent a medical advance as significant as antibiotics (Time Magazine, 1954, 1955; Shorter, 1997). Their introduction is frequently credited with transforming the care of the mad or ‘insane’, enabling the closure of the old Victorian asylums and ushering in the possibility of more humane care based in the community. According to this view, people who would have languished in the back wards of institutions for the whole of their lives could be restored, through drug treatment, to lead normal lives in the outside world. The drugs were said to have brought about the ‘social emancipation of the mental patient’, and to have changed the nature, purpose and location of psychiatric practice (Freyhan, 1955, p. 84). The introduction of antipsychotics and other modern drugs into psychiatry was heralded as a ‘chemical revolution’ that constituted one of the ‘most important and dramatic epics in the history of medicine itself’ (F. Ayd cited in Swazey, 1974, p. 8).

Antipsychotics are not simply believed to be more effective than previous treatments, however. They are believed to be something quite distinct and unique. In contrast to the drugs that came before them, which were regarded merely as a crude means of controlling agitated or challenging behaviour, antipsychotics are thought to work by cleverly targeting an underlying disease or abnormality. They are thought to exert their beneficial or therapeutic effects by counteracting the brain processes that give rise to the symptoms of the most devastating and burdensome of mental conditions—that known as ‘schizophrenia’. With the introduction of antipsychotics, psychiatrists believed they could, at last, alter the course and outcome of a major mental illness, and that ‘for the first time, public mental institutions could be regarded as true treatment centres, rather than as primarily custodial facilities’ (Davis and Cole, 1975, p. 442). The idea that there were proper medical treatments for mental disorders that acted on underlying diseases in the same way as antibiotics or cancer drugs helped to lift psychiatry out of the doldrums, transforming it from a neglected form of social work into what was perceived as a properly scientific activity, and restoring it to its rightful place within the medical arena (Shorter, 1997; Comite Lyonnais de Recherches Therapeutiques en Psychiatrie, 2000). By this account, the introduction of antipsychotics is a story of untainted medical progress.

Yet, for others, antipsychotic drugs are the embodiment of psychiatric oppression, equivalent to the shackles and manacles of previous eras. They have replaced electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) and lobotomy as the main target of criticism of the psychiatric system, and are viewed by detractors as a chemical straight jacket, used to facilitate the control of unwanted behaviour. Many people who have taken the drugs describe the experience as highly unpleasant, like a ‘living hell,’ ‘sheer torture’ or being in a ‘drug prison’ (Breggin, 1993a, p. 57; Anonymous, 2009b). People describe feeling like ‘zombies’ under the influence of the drugs, with their mental capacities dulled and their emotions blunted (Wallace, 1994). For those who are forced to take antipsychotics against their will, the experience is particularly traumatic. Former patient turned campaigner David Oaks, reflecting on his experience of the mental health system in early adulthood, described how the effect of coerced antipsychotic drug treatment ‘felt like a wrecking ball to the cathedral of my mind’ (Oaks, 2011, p. 190). Mental health advocacy groups have argued that such activity constitutes a breach of human rights. Demonstrations against forced drug treatment have become a regular occurrence outside major psychiatric conferences in the USA (Mindfreedom, 2012), and campaigns have also been conducted in England (Figure 1.1), Ireland and Norway. Even those who feel the drugs have been helpful often describe the high price they have had to pay for these benefits. ‘It makes you sane, but you’re not much better off’, commented one antipsychotic user on a medication website (Anonymous, 2009a).

Critics from within the mental health professions have also challenged the view that antipsychotic drugs are a restorative and benign medical treatment. Psychiatrist Peter Breggin claims that antipsychotics induce a form of ‘chemical lobotomy’ and cause permanent brain damage, leading to a form of drug-induced dementia (Breggin, 2008). Furthermore, Breggin and others suggest that the ‘brain disabling’ effect of these drugs is not an unintended side effect, but the intended consequence of drug treatment. This view of antipsychotics as a chemical cosh that stifles mental and physical activity goes back to the time of their introduction in the 1950s, when many clinicians welcomed the new drugs’ ability to suppress normal brain function. Others, however, commented on how the new tranquillisers, later to become known as antipsychotics, had replaced the noise and disturbance of the asylum with the ‘silence of the cemetery’ (Comite Lyonnais de Recherches Therapeutiques en Psychiatrie, 2000, p. 29; attributed to Racamier or Lacan).

Figure 1.1 ‘Kissit’ demonstration, UK, 2005 (Reproduced courtesy of Anthony Fisher Photography)

While criticising antipsychotics was once regarded as the territory of a few extremists, the reputation of these drugs has recently become more widely tarnished through revelations about the activities of the companies that market them. In 2009, Eli Lilly reached the record books for incurring what was at the time the largest fine in US corporate history for the illegal marketing of its blockbuster antipsychotic drug, Zyprexa (olanzapine), in situations in which it had not been licenced. AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson have also been found guilty of illegally promoting their atypical antipsychotics, and revelations that companies had suppressed or minimised evidence of the serious side effects of these drugs, particularly their propensity to cause weight gain and diabetes, has also come to light (Berenson, 2006). Large settlements have been paid out to people who have alleged drug-induced effects of this sort in North America (Berenson, 2007). Moreover, data have been gradually accumulating from brain imaging studies that confirm earlier suspicions that antipsychotics cause brain shrinkage. Nancy Andreason, a leading biological psychiatrist and former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry, acknowledged these findings in an interview with the New York Times in 2008 (Dreifus, 2008). In 2012, British psychiatrist, Peter Tyrer, editor of the British Journal of Psychiatry, went even further, admitting that there is an ‘increasing body of evidence that the adverse effects of treatment [with antipsychotics] are, to put it simply, not worth the candle’. ‘For many’, he suggested, ‘the risks outweigh the benefits’(Tyrer, 2012, p. 168).

Understanding how a group of drugs, initially understood as powerful nervous system suppressants, came to be regarded as a miraculous medical intervention that could successfully counteract the biological origins of mental disease, helps to illuminate how a motley collection of unpleasant and toxic substances could rise to become modern day blockbusters. Antipsychotics started life in the asylums of the mid-twentieth century, but 50 years later they are being prescribed to millions of people worldwide, including children, many of whom have never even seen a psychiatrist (Sankaranarayanan and Puumala, 2007). Aggressive marketing has driven these powerful chemicals, once reserved for the most severely mentally disturbed, out into the wider community. We all need to be aware now of what these drugs are, and what they can do. Antipsychotics have become everybody’s problem.

Use of Antipsychotics

The first drug that came to be classified as an antipsychotic is chlorpromazine, but it is often better known by its brand names—Largactil in the UK and Thorazine in the USA. It was first used in psychiatry in the early 1950s, and it was regarded as so successful that in the following years numerous other drugs aimed at treating psychosis and schizophrenia were introduced. Haloperidol was first marketed in 1958 and, for a long time, it was the biggest selling antipsychotic on the market. Stelazine (trifluoperazine) and perphenazine were also introduced in the 1960s, and Modecate (fluphenazine), the first injectable, long-acting, ‘depot’ preparation of an antipsychotic, was released in 1969. It was followed by Haldol, a depot preparation of haloperidol, and the still commonly used depot injections Depixol (flupentixol) and Clopixol (zuclopenthixol) (see Appendix 1).

In the 1990s a new generation of antipsychotic drugs was introduced, which are sometimes referred to as the ‘atypicals’. These followed on the heels of clozapine, the archetypal atypical antipsychotic, which was reintroduced in 1990, after having been abandoned in the 1970s when its potential to cause life-threatening blood disorders became apparent. The success of clozapine for people who were deemed to have ‘treatment resistant schizophrenia’, along with problems that became apparent with the older drugs, particularly the drug-induced neurological condition known as tardive dyskinesia, encouraged attempts to develop other clozapine-like drugs for schizophrenia and psychosis. Risperidone, also known by its brand name Risperdal, was duly licensed and launched in 1994, and olanzapine, or Zyprexa in 1996. Quetiapine, marketed under the name Seroquel, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1994 and in the UK in 1997.

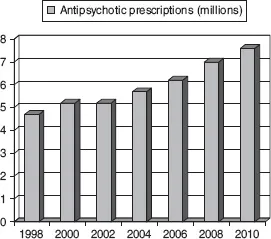

For the first 30 years after their introduction antipsychotic drugs were reserved mainly for the treatment of people with severe psychiatric problems. They were officially recommended for the treatment of people with schizophrenia or psychosis, although they were always administered more widely than this, and were given to many of the inmates of the old asylums, regardless of their diagnosis. Low doses of some of the more sedative antipsychotics were also prescribed to people with sleep problems and anxiety, but such use was not endorsed officially, and they were never regarded as drugs that had a mass market. Since the introduction of the ‘atypicals’, however, the use of these drugs has widened and aggressive marketing has made some of these drugs into worldwide best-sellers. In 2010 spending on antipsychotic drugs in the USA reached a total of almost $17 billion, only just behind anti-diabetic drugs and statins, and ahead of antidepressants (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, 2011). In England, in 2010, 7.5 million prescriptions were issued for antipsychotics in the community alone (excluding the large number of prescriptions issued to patients in psychiatric hospitals)—a 61% increase on the number of prescriptions issued in 1998 (Figure 1.2). The cost of the drugs increased by a dramatic 286% over the same period, with antipsychotics costing the English National Health Service £282 million in 2010. By 2007, they became the most costly class of drug treatment used for mental health problems in England, overtaking antidepressants, which had enjoyed this dubious honour for a decade or more (Ilyas and Moncrieff, 2012).

The success of the new generation of antipsychotics was achieved in two ways. First, marketing campaigns attempted to convince prescribers that the atypical antipsychotics should replace the use of the older antipsychotics for the treatment of people with schizophrenia or psychosis. By 2002, atypical antipsychotics represented more than 90% of all antipsychotics prescribed in the USA (Sankaranarayanan and Puumala, 2007), and, by 2009, they had captured 73% of the community prescription market in the UK (NHS Prescription Services, 2009). A few blockbusting drugs now occupy the majority of this market, particularly olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone (Zyprexa, Seroquel and Risperdal). In 2010 these three drugs accounted for 63% of community prescriptions of antipsychotics in England, and olanzapine and quetiapine alone made up 76% of the costs of all antipsychotic drugs.

Figure 1.2 Trends in prescriptions of antipsychotics issued in the community in England (data from the National Health Service Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 1998–2010)

Second, there has been a concerted effort to expand the indications for the use of antipsychotics in general, so that the atypical antipsychotics could be targeted at the wider population in the way that had proved so successful for modern ‘antidepressant’ drugs like Prozac and Seroxat (Paxil). Companies promoted antipsychotics for use in elderly people with dementia, targeting the staff of nursing homes and pharmacies, despite the fact they had no licence for the treatment of dementia, or agitation in people with dementia, and regardless of accumulating evidence that the use of antipsychotics in dementia shortens people’s lives. Atypical antipsychotics were also promoted for the treatment of common problems including anxiety, depression, irritability, agitation and insomnia (United States Department of Justice, 2009, 2010), and data from the USA and the UK suggest that the majority of prescriptions of atypical antipsychotics are now issued to people who are diagnosed with depression, anxiety or, more recently, bipolar disorder rather than schizophrenia or psychosis (Kaye et al., 2003; Alexander et al., 2011).

The expansion of the concept of bipolar disorder has been one of the key strategies employed to expand antipsychotic use into the wider population. Atypical antipsychotic manufacturers successfully transformed perceptions of the condition from being a rare and highly distinctive form of severe madness, to the common and familiar experience of intense and fluctuating moods. In this manner they were able to capture some of the large population that had previously identified themselves, or had been identified, as depressed (Spielmans, 2009).

Most worryingly, antipsychotics have been prescribed to increasing numbers of children over the last few years, especially in the USA (Olfson et al., 2006). Much of this prescribing has also been justified by giving children the newly fabricated diagnosis of paediatric bipolar disorder, but the drugs are also prescribed, often in combination with other drugs, to children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism and ‘behavioural problems’. Although parents and academics have been at the forefront of the trend to label children with bipolar disorder and medicate them with antipsychotics, drug company money has helped to lubricate this activity and give it respectability by funding research programmes and cultivating leading academics as allies with generous payments for services rendered (Harris and Carey, 2008).

What Are Antipsychotics and What Do They Do?

This expansion in the use of antipsychotic drugs has been dependent on a theoretical framework that casts psychiatric drugs as specially targeted treatments that work by reversing or ameliorating an underlying brain abnormality or dysfunction. The nature of the abnormality is often referred to as a ‘chemical imbalance’, and drug company websites repeatedly stress the idea that psychiatric medication works by rectifying a chemical imbalance. The website for the antipsychotic Geodon (zisprasidone—an antipsychotic used in the USA, but not in the UK), stated in its information about schizophrenia in 2006 that ‘imbalances of certain chemicals in the brain are thought to lead to the symptoms of the illness. Medicine plays a key role in balancing these chemicals’ (my emphasis) (Pfizer, 2006). Similarly, Seroquel is ‘thought to work’, said its manufacturers in 2011, ‘by helping to regulate the balance of chemicals in the brain to help treat schizophrenia’ (AstraZeneca, 2011). Antidepressants like Prozac and Paxil are also said to ‘balance your brain’s chemistry’ (GlaxoSmithKline, 2009) and information on bipolar disorder, or manic depression, suggests the condition is triggered by ‘an imbalance in some key chemicals in the brain’ that antipsychotics can help to ‘adjust’ (Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, 2012).

Information produced by professional organisatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Cure or Curse: What Are Antipsychotics?

- 2 Chlorpromazine: The First Wonder Drug

- 3 Magic Bullets: The Development of Ideas on Drug Action

- 4 Building a House of Cards: The Dopamine Theory of Schizophrenia and Drug Action

- 5 The Phoenix Rises: From Tardive Dyskinesia to the Introduction of the ‘Atypicals’

- 6 Looking Where the Light is: Randomised Controlled Trials of Antipsychotics

- 7 The Patient’s Dilemma: Other Evidence on the Effects of Antipsychotics

- 8 Chemical Cosh: Antipsychotics and Chemical Restraint

- 9 Old and New Drug-Induced Problems

- 10 The First Tentacles: The ‘Early Intervention in Psychosis’ Movement

- 11 The Antipsychotic Epidemic: Prescribing in the Twenty-First Century

- 12 All is not as it Seems

- Notes

- Appendix 1: Common Antipsychotic Drugs

- Appendix 2: Accounts of Schizophrenia and Psychosis

- References

- Index