eBook - ePub

Fixing the African State

Recognition, Politics, and Community-Based Development in Tanzania

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Community-based development' (CBD) or'community-driven development' (CDD) has been the predominant approach to international development in recent years. Drawing on fieldwork and first-hand experience, this book explains why CBD/CDD produces outcomes that are incompatible with its underlying assumptions and intended objectives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fixing the African State by B. Dill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Developing” Dar es Salaam

Across Dar es Salaam, residents struggled to cope with the enormous amount of water left by the El Niño rains that had, over the course of several days in February 1998, swept through the city with unprecedented intensity. Low-lying areas previously unaffected by heavy rains were under several feet of water; water-borne illnesses such as cholera and dysentery had begun to spread as a result of inundated pit latrines; many of the city’s roads, rutted and irregular in dry weather, were no longer passable. The residents of Kipembezo faced an additional problem: the bridge connecting the two parts of the community divided by a seasonal creek had been washed away.1

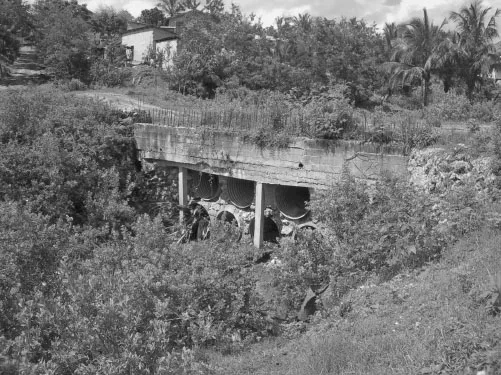

The bridge had been substantial, in terms of size and the water course it spanned. But it was not essential, affecting only a portion of the area’s residents, who, by following a rather lengthy and circuitous path, could still reach the main road to the city. Nevertheless, residents were eager to see the bridge replaced. Kipembezo had a registered CBO, the Kipembezo Development Association (KDA), which immediately rallied its members to contribute cash and kind to the reconstruction effort. The organization succeeded in augmenting the limited resources it had marshaled locally by applying for and receiving a small grant from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The grant provided cash for the purchase of materials but stipulated that the organization’s members and interested community residents, under the direction of KDA, supply the necessary labor. Believing that they still lacked both the resources and the expertise to complete the job, the leaders of KDA appealed directly to the Dar es Salaam City Commission for further assistance. Recognizing a genuine need and its responsibility, officials offered materials but not money, as well as the services of municipal engineers but not their salaries. KDA accepted the terms, paid the salaries, assembled the materials, mobilized the labor, and eventually built a functional though incomplete bridge. The bridge is still in use today (see Figure 1.1).

One can observe similar self-help activities in most, if not all, of Dar es Salaam’s residential areas. While not always successful, community-based efforts to improve roads, renovate schools, collect solid waste, and/or provide potable water are reasonable corollaries to the fact that the majority of the city’s four million residents now live in unplanned settlements. These are areas that grew spontaneously and, in some cases, illicitly. They emerged irrespective of the policies developed and deployed by authorities over the years, and, as a result, their occupants tend not to enjoy benefits such as basic infrastructure, services, or secure land tenure that those who built on surveyed plots in planned residential areas do. These settlements, which are the result of rapid population growth, and the failure and disinclination of the organizations that constitute the state to manage it, should not be referred to as squatter areas, however; most landowners in these areas are not illegal occupants of the land although they may have developed it without following the requirements of the law.2

Figure 1.1 The new bridge in Kipembezo. Photo by author.

The growth of Dar es Salaam’s unplanned settlements, both in terms of the quantity of distinct areas and of the proportion of the urban population they contain, has been nothing short of phenomenal. The United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-HABITAT) has claimed, for example, that the number of unplanned settlements has gone from 40 in 1985 to 150 in 2003.3 More striking, perhaps, is the claim that while 36 percent of Dar es Salaam’s population was already living in unplanned areas in 1967, the proportion nearly doubled to 70 percent by 1995.4 This final figure is similar to current colloquial estimates and is typically found in government reports. But it may underestimate the true extent of the situation. Looking at property tax data bases and extrapolating from studies that find higher house occupancy rates in unplanned areas, urban planning professor, Lusagge Kironde, has concluded that “the proportion of the City’s population living in unplanned areas is likely to be higher than 80 percent.”5 While a true number is unattainable, the undisputed trajectory of growth and the current extent of unplanned settlements in Dar es Salaam clearly bolsters Garth Myer’s claim that, in this particular African city, the informal has become normal insofar as “informal settlements are the life of the city.”6

Understanding how Dar es Salaam has become a sprawling agglomeration of unplanned settlements requires discovery of the ways in which successive regimes have viewed and managed the city’s development. In this chapter, I will provide a dynamic account of the city’s transformation over the past century and a half. Drawing on a substantial body of secondary literature, I will argue that, since its inception, Dar es Salaam has developed with little attention given to the interests of its African residents. In an effort to explain why and with what effect the concerns of the urban majority have been consistently eclipsed by the exigencies of trade and administration, I will explore the following questions: How have colonial and postcolonial state actors sought to control and direct Dar es Salaam’s evolution and what have been the most notable impacts? Why has self-help been a long-standing norm and ineluctable necessity in the residential areas allocated to and claimed by Africans? In short, I seek to provide the necessary historical background with which to contextualize current efforts to promote CBD/CDD.

Origins

The unplanned residential sprawl that is emblematic of Dar es Salaam today would have seemed unlikely at the city’s birth approximately 150 years ago. No one could have anticipated that the scattered villages that once occupied this stretch of tropical East African coastline would eventually evolve into a vibrant, heterogeneous city of four million people, or that the majority of its current occupants would be left to fend for itself in terms of housing, services, and livelihoods. And yet it is clear with the benefit of hindsight that the current arrangement is without doubt the direct consequence of the city being founded by and developed for non-African interests. Dar es Salaam really began as a center of trade and administration, and, as will be discussed in greater detail below, the trajectory of its development has long been dictated by the interests of the few in control of these functions rather than the needs of its many African residents.

Sultan Sayyid Majid of Zanzibar first conceived of Dar es Salaam in 1862, with actual construction beginning a few years later. His reasons for taking the extraordinary step of establishing a territorial foothold on the mainland are, it seems, captured both literally and metaphorically by the name he bestowed upon the new town. Arabic for “harbor of peace” and/or “haven of peace,” Dar es Salaam was in fact built on the shores of a large, natural harbor and thus an ideal nexus for trade between the Indian Ocean and the African interior; the site is but one of six significant harbors on the coast of East Africa.7 But the Sultan may have also hoped that the town would prove to be a political sanctuary of sorts, one that would allow him “to escape not only the anti-slavery pressures of the European delegations localized in Zanzibar town, but also the unruly agitation of the urban elite in Bagamoyo, the caravan route terminal situated 40km to the north of Dar es Salaam.”8 In short, the Sultan sought to create a new space for economic advancement, a town that would insulate him from encroaching Europeans and whose development would be propelled by local plantation agriculture and caravan trade with the interior.9

Zanzibar’s interest in the town came to an abrupt halt with the death of the Sultan in 1870. His brother and successor, Sultan Barghash, stopped construction and allowed the site to deteriorate, “leaving a few stone houses around the inner bay and 200,000 coconut palms covering the whole site.”10 Its potential as a locus of trade and administration had lain dormant for nearly two decades, when it reemerged as an important launching pad for Germany’s colonial ambitions. The path to eventual colonization was blazed by the German East Africa Company, which persuaded Sultan Barghash to grant it trading rights in Dar es Salaam in 1885. Two years later, the company secured the right to collect custom duties in the town.11

Ultimately, it was the technological advancement of the steamship that brought to light Dar es Salaam’s functional advantages with respect to trade and secured its position as a colonial capital. The nineteenth century had witnessed the gradual replacement of sailing vessels with the much larger, ocean-going steamships.12 This facilitated a significant expansion in the quantity of trade between Europe and Africa. For example, trade in palm oil on the other side of the continent was greatly impacted by the establishment of regular steamship service between Britain and West Africa in 1852.13 Bagamoyo, the longstanding caravan terminus and vibrant commercial center to the north of Dar es Salaam, lacked a sheltered, deep-water harbor. It was thus not practically suited to accommodate the volume of trade advanced by the steamship. “The German Imperial Government, which initially used Bagamoyo as a capital for the new sphere of German influence,” transferred the seat of government to Dar es Salaam on January 1, 1891; it thus became the new capital of German East Africa.14

For the next quarter of a century, the city played a vital role in servicing the colonial agricultural economy. As a consequence, Bagamoyo’s share of trade fell, whereas Dar es Salaam’s grew from 9 to 25 percent from 1890 to 1903.15 The city was the linchpin in Germany’s control of a vast swath of the African interior, an area that includes the present-day Tanzanian mainland, a small piece of Mozambique, as well as the independent nations of Rwanda and Burundi. While the total population of Dar es Salaam was still modest by the end of the German period—approximately 19 thousand residents in 1916—it had increased more than sixfold since 1887.16 Arguably the most important pattern to be established by the conclusion of German control, however, was the tripartite racial division of the city and the profound lack of concern shown for its African residents. As I will discuss in the following section, the willful neglect of the city’s majority during both the German and British periods of colonial control did much to set the stage for the growth of unplanned settlements that are the dominant feature of contemporary Dar es Salaam.

Zone of Neglect

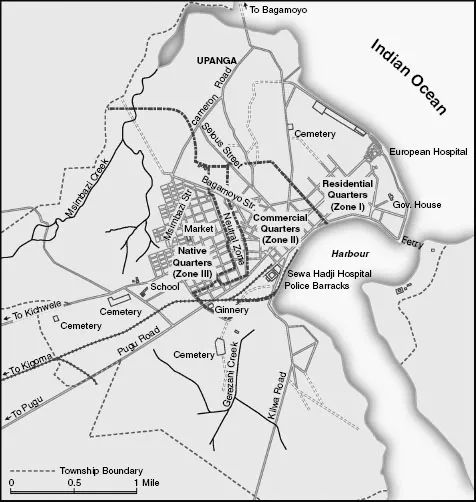

The overarching principle of colonial urban policy in Dar es Salaam was segregation. This was true for the Germans, who were the first to define discrete zones of residential settlement for Europeans, Asians (i.e., primarily Indians), and Africans in 1891 (see Figure 1.2). It was also the case for the British, who administered the territory of Tanganyika and hence its capital, Dar es Salaam, as a League of Nations Mandate at the conclusion of World War I.17 Like their predecessors, the British brought about the city’s tripartite racial division in the absence of any official policy of segregation.18 Rather than invoke and craft policy around biological definitions of race, which would have run afoul of Tanganyika’s Mandate status, colonial authorities ensured the outcome of racial segregation through the creation and enforcement of separate building standards for the homes in each of the three zones.19

Figure 1.2 Colonial Dar es Salaam’s three zones. This map appeared originally in Taifa: Making Nation and Race in Urban Tanzania by James R. Brennan. Copyright © 2012 by Ohio University Press. Map provided by Claudia Walters. This material is used by permission of Ohio University Press, www.ohioswallow.com.

Europeans primarily resided in Zone I, a large area of premium land that included the original German quarter that extended to the northeast of the city center, as well as nascent settlements along the coast to the north. The Asian population was concentrated in Zone II, which consisted of the land adjacent the harbor and the commercial area that was essentially the city center. Africans were relegated to Zone III, a parcel of land that did not have direct access to either the ocean or the harbor and which was separated from the rest of the town by an empty, sanitary corridor.20

The particular restrictions and requirements that applied to each of the three zones were contained in the revised building ordinance of 1914.21 It reaffirmed the initial provision that Zone I was exclusively for European style residential buildings. But it went further in specifying what this meant, requiring, for example, that “all rooms were to have at least one window that measured three-fourths of a square meter, and all toilets were to have flushing mechanisms and covers to contain odors.”22 Zone II was set aside for residential or commercial buildings that were constructed out of sturdy materials. Zone III was for native style buildings of any type.

Although the Germans were the first to define the three zones and create the sanitary buffer between Africans and the rest of the city’s residents, they had made little effort to enforce the segregation of the races before the outbreak of World War I.23 As a result, the zones were by no means racially homogeneous when the British assumed control of the city. In an effort to align actual residential patterns with the ideal of racial segregation, they deployed two specific tools.24 The first was to enforce building and sanitation codes. For example, Africans living in Zones I and II were prohibited from making structural improvements to their houses in order to comply with the relevant building regulations. Those whose structures were not in compliance with the relevant codes and/or who did not accept the offer ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 “Developing” Dar es Salaam

- 2 Life on the Ground

- 3 Recognizing Community

- 4 Rendering Political

- 5 Fixing the African State

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index