- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Michal Nahman traces different kinds of 'extraction': the practices of human egg harvesting in different national contexts; the political economic consequences of such extraction for the women involved and the ways in which this has consequences for nationalism and race or 'Israeli extraction'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Extractions by M. Nahman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Extractions

The ‘terrorist’ in the in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinic: notes from research in a private Israeli hospital

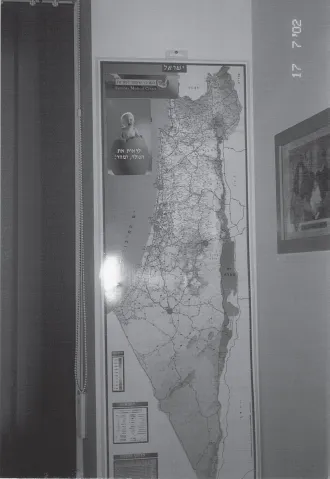

Behind Dr Shmuel’s desk and to the right on the wall was a large map of the State of Israel (see Figure 1.1). It included but did not mark the Occupied Palestinian Territories and the Gaza Strip. It was a topographical map, with major roads and cities marked by dots and dashes. On this map, five round, coloured stickers were affixed, marking the location of the company’s five satellite clinics in various parts of the country. At the top left-hand corner of the poster was a glossy company brochure. On this brochure was a picture of a blonde baby popping out of an oversized chicken’s egg. The caption in Hebrew read: ‘Lir’ot et ha-nolad, ve-maher!’ ‘To see the [child that is] born, and fast!’ On the wall next to this map was a photograph of four European-looking people: the doctor, a woman, a man and a baby, presumably two of the doctor’s happy new parents with their baby.

Next to the photograph was a large whiteboard. I didn’t take a photo of it for reasons that I think will become obvious. On it was a large drawing, in black marker ink, of two men. One, scruffy faced, with a large nose, overgrown beard and menacing eyes, wielding a large knife. In the context of the Al Aqsa Intifada that was then raging, this man could be none other than the Palestinian1 ‘Terrorist’. The other, clean-cut European-looking, was dressed in army fatigues with the acronym Tsahal, ‘IDF’ (Israel Defense Forces), written on the front of his shirt. He was holding a large rifle and had a speech bubble above his head. The writing in the bubble said: ‘‘Am Israel hai,’ ‘The nation of Israel lives.’ This is a common religious phrase of exaltation and survival, which little children and other celebrants sing in Israel as in the Diaspora when marking Holocaust Remembrance Day. Here, however, it resonated as well with the prevailing sentiment that Jewish Israelis ‘are fighting for survival’ – what politicians, the media, egg recipients, my Israeli family and friends alike repeatedly called ‘milhama ‘al ha-bayit’ or ‘a war over home’.2 In the clinic, the statement written on the board, ‘‘Am Israel hai’, is one in which the survival of the European Jewish self, nation and state are rolled into one. During the brief period since the founding of the state in 1948 and including the time covered in this research, everyday violence was intimately co-inscribed by heteronormative family values3 and imaginaries of racial superiority of whiteness. The very presence of images of the family and the nation in the clinic in Israel may be unsurprising, given how historically the reproduction of nations and states has been tied to the reproduction of the individual (Yuval-Davis, 1989, 1997) and given the banality of militarization in Israeli society. But here we have the ‘Terrorist’, in a private Israeli clinic where in vitro fertilization (IVF) is very costly.

Figure 1.1 Map of Israel with baby and family

Source: The author.

There is an uncanny kinship between these images of the Israeli soldier and Palestinian terrorist confronting each other, and the blonde baby coming out of a chicken’s egg, on a map of the State of Israel, next to a picture of a happy Jewish family. Something familiar and echoes of narratives of improvement, security, protection of nation/family and ultimately of a blonde child reside here. It is like the recent history of Ashkenazi Jews (Jews who self-identify or are identified by others as coming from Europe), conflated with Zionist state ideologies of victimhood and violence is written on the wall. This is about fears and anxieties over racial extraction, the removal of Palestinians from the land, and taking eggs out of women’s bodies for profit. The images described above show just how nation, race, war, the individual self and egg donation were at once overlapping and mutually constituting ‘domains’. As I argue throughout this book, the ‘individual’ stands in for the ‘collective’ in Israel. So too egg donation and the nation can stand in for one another. After observing these images I could not follow the conversation that the women in the room were having. I tried unsuccessfully to make sense of what I had just seen. When I asked around, I found out that the drawing was made by Dr Shmuel’s ten-year-old son and his friend who were bored while spending a day at the clinic a few months earlier.

Extractions ethnographically maps and traces relations of removal, fertilization, transport and transfer of human eggs between women’s bodies and clinics in Israel and Romania in 2002 (since 2006, Romania no longer permits the selling of eggs) at the height of the Al Aqsa Intifada (the Second Intifada). One year after 9/11, this was also a time of heightened concern with nationalism, security and borders in the global North. Oocyte extraction practices are indexical of this time. Extractions deals centrally with the questions: How do everyday practices and procedures of Israeli egg donation create and reinforce nationalized, racialized bodies, borders and ideals? How do we make the study of something as unfixed and complex as egg donation, race, war, gender and class coherent without shutting it down? How do we employ a critical sensibility for globalization and gender in this process? This book is an experiment in doing these things all at once. Whilst being attentive to the influence of Jewish law on Israeli egg donation, the focus here is on other influences on the political and material dimensions of reproductive technologies. It is a concern with how practices and technologies of reproduction produce Israeliness and how Israeliness produces reproduction. Whilst this has been done before to some extent (Portugese, 1998; Kanaaneh, 2002; Weiss, 2002), the integral nature of the occupation and violence is brought from the margins of the narrative to its centre. ‘Israeli extractions’ (that is, identities and ova) get made in complex and messy ways that ‘interfere’ with both state and scholarly discourses about Israeli reproduction. Writing about this is also an ‘interference’ (Haraway, 2004). Gendered citizens are simultaneously situated along axes of religion, reproduction, class and race, in relation to official discourses about multiculturalism that are in themselves both celebratory and cautious. With overlaps, disjunctures and unlikely juxtapositions, the reader is asked to reflect critically on the ways in which we represent these things.

Transnational reproduction and migration are linked concerns, and there is a historical and ideological overlap in Israel between citizenship law and egg donation law. In the year 2000, it was clear that (despite disagreements) the authorities had decided that the donor’s genetics did not matter for ova donation and for the importance of maintaining a Jewish family (Kahn, 2000). Yet over the ten years since then, it seems that a different perspective has been adopted in which the genetic/religious/racial make-up of the donated egg has gained importance. This has occurred both in response to the perceived threats to the state from non-Jewish Asian and African migrants and Palestinians, and the pressures for the Israeli state to be a global player in the marketization of cross-border reproduction.

Israeli borders are being hardened through the creation of laws concerning loyalty to the Jewish state. The right-wing Israel Beiteynu Party (translated as ‘Israel Our Home’) recently proposed a series of five ‘citizenship equals loyalty’ laws, which have been and continue to undergo readings in the Israeli Knesset (Parliament). One law proposes stripping Israeli citizenship from those who are unwilling to declare loyalty to the Israeli state. Whilst that particular proposed law was not approved, another version of the law has been approved by the Cabinet and is awaiting final approval by the Knesset. This law requires non-Jewish people wishing to become citizens of Israel to declare their loyalty to ‘the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’. In the year 2010, the Israeli government passed an Egg Donation Law that bans cross-religious donation, a move that seems to conflict with both the Israeli state policy of supporting a multicultural state and Jewish religious authorities’ teachings on the kinship and citizenship significance of donor eggs.

There has been a genetic reinscription of race (El Haj, 2007), and the ethnographic research that I conducted in 2002 already bore witness to this (also this law, although only passed in 2010, was already written almost entirely by 2002). So, even if you are not born to a Jewish mother, you can be a citizen by reaffirming the centrality of Jewishness to the state. And in egg donation, you must have come from the egg of a Jewish woman to be counted as a legitimate Jewish citizen. Equally, you cannot have come from the egg of a Jewish woman if you were born to a non-Jewish woman, according to this new law. Affiliation to the state is being negotiated in hearts and genes. The state’s lawmakers use Jewish kinship thinking in ways that shift according to the complex context. These are financial, reproductive and border/citizenship concerns all folded into one another. They often hinge in public discourse on ideas of the state needing to protect itself from the violence of Israel’s enemies both present and past. Whilst the material gathered in this book predates these policy changes, they give evidence to the ways in which common sense and everyday forms of racism and border disputes fed into the contemporary global bioeconomy.

A central trope in lay and scholarly discussions about both citizenship and reproduction is ‘pronatalism’. Ideas about the Israeli state’s pronatalism and ‘world leader’ status may be a discourse that perpetuates an ideal of Israel as a Jewish, ‘chosen’ nation rather than a nation-state founded on expropriation of land, expulsion. These competing myths of the nation can also produce different narratives about reproduction. The peremptory assertion of Israel’s pronatalism demands detailed microscopic unfoldings of how that process happens. Extractions attempts to unravel those enactments (Mol, 2002) of the body and the nation by switching between the microscopic stuff of individual bodies to the scale of the nation in a kind of ‘synecdochic ricochet’ (explained further below; also see Nahman, 2008; Hayden, 1995). Where the ‘part’ stands in for the ‘whole’ but like the bullets and bombs that Israelis and Palestinians were dodging at the time of this research, there is a constant move back and forth between these so-called ‘domains’ of knowledge and practice. This is a historicized feminist practice of writing. Exchanges in eggs, talk about eggs, legislation regarding the importing and donating of eggs, and processes of extracting, fertilizing and freezing eggs that occur in disparate places, and in specific moments in time perform (undo and reify) Israeli nationalism, identity and borders. In nationalism and nationalistic practices, nations turn particular symbols into synecdoche. The hijab standing in for the Muslim woman and the so-called dangers of Islam to Europe is one example (Bowen, 2007, cited in Vertovec, 2011). If nation-states use synecdoche as a way of imagining ‘the other’ and therefore of constituting themselves, then using synecdoche to analyze nationalism is using an emic (or indigenous) term in the study of nationalism. I will return to this below.

In the social sciences, ‘the body’ has been studied as a metaphor for a society’s concerns about its borders. In earlier anthropological accounts, these concerns shaped cultural practices around purity, dirt and contamination (Douglas, 1966). Structuralist, symbolic and psychoanalytic arguments were used to explore these relationships. In contrast, social classes (and nations as larger examples of these) were seen to be produced through the repetition of daily bodily praxis (Bourdieu, 1977). For Douglas, the relation between the body and the community is created through the symbolism between structures and for Bourdieu it is created through the repetition of everyday practices that generate social structures. Both perspectives allow for the idea that aspects of the body transmit meaning about borders of the collectivity and that, in turn, the body’s meaning is shaped by the larger collectivity. Nevertheless, the micro processes of the body through which this larger collectivity is formed have been seen in the work of feminist accounts of the body (Martin, 1991; Ginsburg and Rapp, 1991, 1995; Franklin, 1997). Extractions contextualizes these practices within the global markets that are opening up to facilitate reproduction.

Race, IVF and parenthood have been examined in the USA and UK (Thompson, 2005; Wade, 2007), while anthropology has dealt extensively with broader concepts of reproduction and notions of exchange in general (Konrad, 2005; Strathern, 1988, 1995). Studies of IVF and reproduction in India (Bharadwaj, 2006a, 2006b; Gupta, 2006) have questioned the connections between neoliberalism, the state, religion and reproduction. Scholars studying the Middle East (Tremayne, 2006; Inhorn, 2003; Zuhur, 1992) have analyzed relationships between Islam and reproduction. Embodiment and medicalization have been central concerns of recent ethnographers of Israeli reproduction (Teman, 2010; Ivry, 2009). Medical ‘tourism’, cross-border reproductive care and medical migration have been gaining significant scholarly attention from within anthropology, law, sociology, bioethics and other fields (Roberts and Scheper-Hughes, 2011; Inhorn, 2011; Gürtin, 2011; Shenfield, 2011; Storrow, 2011; Dickenson, 2007).

Israeli IVF has been examined, with reference to the everyday practices and the rabbinical and state discourses around ‘Jewish kinship’ (Kahn, 2000). Along with other Israeli scholars I argue that there are many ways in which reproductive technologies in Israel are tied to ‘the nation’, particularly through militaristic metaphors (Ivry, 1999, 2009), and through cultural ideas of nature and motherhood (Teman, 2003, 2010). Extractions ethnographically extends this field and looks at the political, economic and ethical dimensions of the unequal positions of women in differently positioned societies, and illustrates how reproductive technology relates to the contemporary context of Israeli state politics. The discursive practices of ova donation that I observed create novel relationships between the individual, reproduction and the Israeli state. With its attention to global economic and Israeli political ‘cultures’, this book thereby contests the rather more exclusive focus on Jewish ideals of pronatalism.

This book presents Israeli accounts of eggs as a resource that is in ‘shortage’; one that can ‘make more disposable people’; and is narrated as being forcibly removed (through dikkur, stabbing or poking); ‘returned’ into different women’s bodies; embodying a ‘promise’ for a child; something explosive; and providing sources of income for donors and clinicians. The research phase of this project involved a nine-month study conducted in Israel and Romania between January and September 2002. Qualitative methods of participant-observation in Israeli IVF clinics, and open-ended interviews with doctors, nurses, Israeli (Jewish and Palestinian) ova recipients, (Israeli and Romanian) ova donors, lawmakers, lawyers and patient advocates were undertaken in the data-gathering phase of the research. Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were carried out with 25 ova recipients and recipient couples, 2 Israeli ova donors, 20 Romanian ova donors, 5 Israeli IVF doctors, 3 representatives of the Israeli Ministry of Health (one of whom is a rabbi and gynaecologist and two of whom are lawyers), 2 egg donation activists, a lawyer who won a key case at the High Court of Justice for importing Romanian eggs, and numerous other healthcare professionals and clinic staff. I analyzed this material qualitatively, looking for emerging patterns in how ideas about egg donation were being discursively produced. The arguments elaborated below emerge directly out of this research. Extractions examines both Jewish and Palestinian experiences of assisted reproduction in Israel. It does so at the juncture of the transnational movement of reproductive substances.

Anthropology makes culture: on the particular and the universal

Israeli egg donation is costly, people must be able to pay initially out of pocket for treatments, are urged to undergo as many possible treatments as necessary and subsequently often fall into debt. These are classed and racialized outcomes of the strong push to reproduce in Israel. A racial topography of egg donation is found in Israel that is similar to the racialized practices of egg donation in other Western contexts. This similarity is crucial because the anthropological endeavour to find ‘the particular’ can sometimes make us the handmaidens of hegemonic nationalisms. A preference for analytic attention to the particulars of Jewish history and the inception of the Israeli state can lead to an over-attribution of these particular aspects to Israeli reproduction as a whole. The focus on histories of anti-Semitism, religious division between Jews and non-Jews, or even the secular–religious split amongst Jews to the exclusion of other aspects (internal racism, internal class divisions, cross-national similarities with other Western countries) can inadvertently reproduce the tropes and myths of the founding of the state rather than merely explain them.

For instance, Jewish Israeli women accept and even desire ova from Romanian women, regardless of the religion of the donor and recipient because they are white and European (Nahman, 2006). Conversely, Jewish Israeli women will rarely admit that they would accept ova from Palestinian women. In addition, the everyday practices of Israeli IVF clinics have been shown to reinforce heteronormative values, even as the state attempts to ‘pinkwash’ the occupation by promoting its pro-gay stance. Transnational Israeli practices of oocyte extraction, transport and transfer (the technical term for inserting an embryo into a woman’s uterus) practices embody the Israeli concern over borders and are, in themselves, a way of allowing Israelis to ‘stay put’ given the transnational mobility of eggs. One might expect that transnational ova donation practices reproduce the State of Israel as ‘globalized’ and ‘transnational’. And they do. But they also reproduce ideas and practices of the Jewish nation-state through practices of transnational ova donation. These practices involve movement across national borders that reproduce Israeliness as Europeanized and Jewish, reinforce the banality of crisis and allow subaltern Israelis to identify and resist the national body in its hegemonic form. In all of this, Romanian women are not just an exploited global resource, but also active participants who inter-cumulate. The practices of egg donation described here in their minutiae are telling a story about national aspirations, politics of ethnic cleansing, eugenics and everyday crisis, violence and victimhood.

A layer of Israeli inequalities is that which despite official laws in Israel that deem all of its citizens to be equal, the realities of everyday life dictate that one must be Jewish in order to be a legitimate citizen, with equal access to good jobs, healthcare and education (Dominguez, 1989; Peled, 2004; Liebman and Don-Yehiya, 1983)....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Glossary

- 1 Extractions

- 2 TheoristSellers

- 3 EmbryoMethod

- 4 Repro-Migrants

- 5 Borders

- 6 ExplosionCrisis

- 7 Synecdoche

- Notes

- References

- Index