eBook - ePub

Theatres of Immanence

Deleuze and the Ethics of Performance

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theatres of Immanence

Deleuze and the Ethics of Performance

About this book

Theatres of Immanence: Deleuze and the Ethics of Performance is the first monograph to provide an in-depth study of the implications of Deleuze's philosophy for theatre and performance. Drawing from Goat Island, Butoh, Artaud and Kaprow, as well from Deleuze, Bergson and Laruelle, the book conceives performance as a way of thinking immanence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theatres of Immanence by Kenneth A. Loparo,Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Immanent Authorship: From the Living Theatre to Cage and Goat Island

I want to begin this chapter by exploring the extent to which the dual notions of immanence and transcendence might be used to differentiate specific approaches to authoring performance. The concept of immanence, I will suggest, has implications for how we think about a variety of forms of authorship, including both collaborative, collective devising and directing. Indeed, I want to propose that immanence provides a productive way to consider the relationship between these authorial modes. Our investigation of immanent authorship will begin with an elaboration of immanence and transcendence as philosophical concepts: conceived by Deleuze as the two ideal poles of a continuum of relation to creative production, with the former tending towards a ‘bottom-up’ approach in contrast to the top-down tendency of the latter. Secondly, I want to look at the resonance between these ideas and those of the Living Theatre as one company that might be understood to belong to a broader ‘collective creation’ movement – an emergent tendency within theatre companies, particularly in and around May 1968,14 towards undoing the hierarchies and divisions of labour that had become the normative mode of organization with respect to theatrical creativity.15

Although the company received the greatest critical acclaim for earlier works such as The Connection (1959) and The Brig (1963), the Living Theatre are best known for Paradise Now (1968), a piece that Stephen J. Bottoms refers to as one of the ‘countercultural landmarks’ of the 1960s (Bottoms 2006: 238). Collectively created while the company were in exile in Europe and subsequently toured around the United States during the politically and socially volatile years of 1968–69, Paradise Now is frequently cited by scholars as exemplary of the concern with presence, and the rejection of representational theatre, understood to characterize the American avant-garde theatre (or ‘alternative theatre’ or ‘Off-off Broadway’ theatre) of the 1960s. However, as well as ensuring its persistence, the notoriety of Paradise Now has arguably also damaged the legacy of the Living Theatre, particularly insofar as the piece tends to be reductively represented as a pure and simple ‘affirmation of live, unmediated presence’ (Copeland 1990: 28). Much derided in subsequent critiques by Christopher Innes (1981, 1993) and Gerald Rabkin (1984), the company are often construed as vulnerable to deconstruction given their appeals to notions of “truth” and “authenticity”; they act as the ‘straw-man’ for Derridean performance theory to the extent that they are understood to trust speech over script, and the body over language, as the means to locate an inner self.

Nevertheless, this chapter will suggest that we should be wary of allowing such deconstructive critique to prevent us from seeing the value in the immanent experiments of the Living Theatre, as we know that Deleuze and Guattari did.16 Such experiments include a range of techniques for desubjectifying performance, including not only collective creation but also improvisation and the use of chance procedures. We will examine each of these in what follows, drawing in insights from the Living Theatre’s collaboration with John Cage and contrasting their approach to critiques of collective creation and improvisation by their contemporary, Jerzy Grotowski. In turn, we will move on to explore how immanent authorship is manifest in the work of former Chicago-based company Goat Island, noting from the start how the company affirm the desubjectifying powers of collaboration, but without abandoning the role of the director.

Founded in 1987, Goat Island was a collaborative performance group, directed by Lin Hixson and formed of the core members Matthew Goulish, Bryan Saner, Karen Christopher, Mark Jeffrey and Litó Walkey. During their 20 years of creating work, the company earned both respect and fascination in the field of performance for their commitment to the affective potential of intricate choreographies performed by nonexpert bodies, and the capacity of a slow, genuinely collaborative research and creation process, which starts from a state of not knowing, to generate new thoughts and unexpected sensations. In 2006, Goat Island announced that their ninth performance, The Lastmaker (2007), would be the last work they would create as a company before individual members went on to pursue new projects and collaborations, such as Goulish and Hixson’s initiative Every House Has a Door.

The connection between Goat Island and Deleuze has already been explored in the writings of founding member Matthew Goulish, as well as in the work of performance scholars such as the company’s UK archivist Stephen J. Bottoms, and David Williams. All three have exposed some of the Deleuzian aspects of Goat Island in a range of important observations (see Bottoms 1998; Williams 2005; Cull and Goulish 2007). For instance, in writing about the process of creating the company’s eighth performance – When will the September roses bloom? Last night was only a comedy (2004) – Goulish evokes notions of ‘stuttering’ in performance and a ‘zone of indiscernibility’ between human and animal that clearly evidence an engagement with Deleuze’s thought. Likewise, his earlier monograph, 39 Microlectures: In Proximity of Performance (2000), draws on the concepts of ‘deterritorialization’, the machinic and differential repetition.17 As, Bottoms has noted, it is not that Goat Island have ‘consciously sought to translate Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas into the performance context’ (Bottoms 1998: 434), but nevertheless their approach to the creation of performance – as collaboration, as becoming – registers their affinity to the values of Deleuze’s ontology.

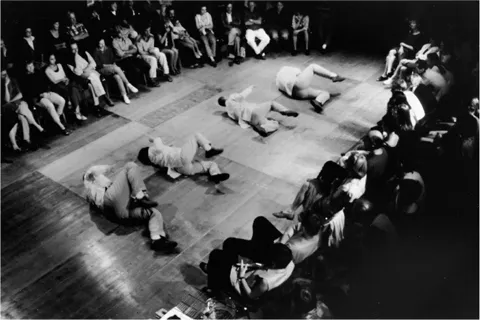

Image 1 Goat Island, It’s Shifting Hank (1994). Photograph courtesy Belluard Bollwerk International Festival, Fribourg, Switzerland, in performance, 1994. Pictured left to right: Timothy McCain, Karen Christopher, Matthew Goulish, Greg McCain

Here, I want to focus on the approach to collaborative authorship and directing that Goat Island developed over their 20 years of making work. Immanent authorship, the company allow us to make clear, is not a matter of ‘freeing’ the author from all rules or constraints. In contrast, we find that, for Goat Island at least, immanence is often to be found where we least expect, for instance in modes of authorship that are based on the imposition of rules and constraints, that serve to preserve rather than homogenize difference within a process of collaborative authorship. However, before we enter into the practical details of these approaches, I want to go into more depth regarding the philosophical background to the concept of immanence and explore, in particular, its relationship to the notion of ‘the subject’ and, hence, ‘the author’.

To have done with God and the Subject: Immanence in philosophy

As I touched on in the Introduction, immanence and transcendence are distinct modes and different ways of understanding creativity and organization. In some forms of organization – whether we are thinking in terms of ontological, social or artistic processes – creation or the production of form relies on ‘a transcendent instance of command’: some thing that functions as a leader, director or author from a position outside the process itself (Holland 2006: 195). In turn, we can say that this transcendent ‘thing’ need not take the form of a person, but could equally be a different kind of body, like an idea. Whatever form it takes, the role of this transcendent figure is ‘to guarantee coordination’, to impose organization top-down on the chaos of processes or, again, to conceive what to create from the material and to execute that conception (Holland 2006). As Eugene Holland has explained, transcendent modes of creation are those in which the ‘modes and principles of … organization’ are external to the activity in question – they are neither part of that activity, nor have they issued from it (Holland 2006). In contrast, immanent modes of organization and creativity allow coordination to emerge bottom-up, and the ‘modes and principles of … organization’ to come from within the processes themselves, not from outside them. There is no leader, director, author or transcendent idea that commands coordination and organization from without; rather, ‘coordination arises more spontaneously and in a manner immanent to the … activity’ (Holland 2006). The material bodies involved in the creative process do not obey commands issued from a transcendent source, but generate their own rules and forms of creation.

Initially articulated in the context of theological accounts of the nature of the relationship between God and worldly creatures, in Deleuze immanence becomes a secular, ontological principle, which in turn can inform our understanding of creation in an artistic context (indeed, Deleuze will make no distinction between ontology and aesthetics). In Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, Deleuze says that his concept of immanence is built up from ‘the great theoretical thesis’ of the seventeenth-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza; namely, the notion of existence as ‘a single substance having an infinity of attributes’ and, correlatively, of bodies or ‘creatures’ as ‘modifications of this substance’, produced without the intervention of ‘a moral, transcendent, creator God’ (Deleuze 1988: 17). As Beth Lord has outlined, the established theism that dominated the Dutch Republic at the time was committed to an image of an ‘anthropomorphic, intentional God’, in contrast to which Spinoza proposed an immanent God, manifest in nature (Lord 2010: 4).

For Deleuze, writing three centuries later, the notion of a transcendent entity that acts as the condition for the creativity of the world persists, but in the form of human subjectivity rather than a God figure. This is, to a great extent, the legacy of Kant. As Todd May summarizes, Kant inaugurates a philosophical tradition that is

in thrall to a human subjectivity that abandons God not by overthrowing transcendence but by gradually usurping God’s place in it. The primacy of the human subject is not a turn to immanence, not an immersion in the world, but transcendence carried on by other means. (May 2005: 28)

Above all, this transcendent thinking manifests itself in understandings of the relationship between mind and matter; hence its significance for theorizing artistic creativity as well as ontology. After Kant, human subjectivity is construed as that which constitutes the meaning of the material world from a position outside or beyond that materiality. As May makes clear:

Constitution does not imply creation. It is not as though there was only mental substance and then, by some miracle, physical substance was created from it. What is created is not the material but the world. The what it is of the material world, its character, is constituted by the mental world, woven from the material world’s inert threads into a meaningful complex. (May 2005: 29, emphasis in original)

According to such a perspective, it is the interaction of consciousness, understood as the special and unique substance of human subjectivity, with matter that enables the world to become meaningful. In this way, it is not just that transcendence posits a fundamental dualism, but that this dualism institutes a hierarchy in which the subject becomes sovereign over all that it surveys. In this way, May concludes, the transcendence of the subject ushers in the subordination of difference to which Deleuze and contemporaries like Derrida so strongly object.

Only that which … conforms to the conceptual categories of human thought is to be admitted in the arena of the acceptable. Physicality, chaos, difference that cannot be subsumed into categories of identity: all these must deny themselves if they would seek to be recognized in the privileged company of the superior substance. (May 2005: 31)

For Deleuze, this transcendent thinking is a kind of illness; ontological dualism is what he calls a ‘philosophical disease’, passed on from one generation of philosophers to the next. But some philosophers – such as Spinoza, but also Nietzsche and Bergson – were less susceptible to this disease than others, and become the resources that enable Deleuze to develop an alternative, immanent account of the relationship between subjects and the world, between beings – including human beings – and Being, in the sense of existence in general. Being, Deleuze says in Difference and Repetition, is univocal: ‘Being is said in a single and the same sense of everything of which it is said, but that of which it is said differs: it is said of difference itself’ (Deleuze 1994: 36). Or again, to take a quote from Deleuze’s second book on Spinoza, consider the idea that there is ‘one Nature for all bodies, one Nature for all individuals, a Nature that is itself an individual varying in an infinite number of ways’ (Deleuze 1988b: 122). Another way to say this might be to say that difference is what all things have in common, for Deleuze; or, further, that because nature differs, what all things have in common is that they are not ‘things’ at all, but processes of ceaseless variation, change or creativity. And this includes subjects. In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari ‘reject dominant “humanist” models of subjectivity focused on the integrity and unity of a single self’ (Robinson and Tormey 2010: 23), when they say that ‘The self is only a threshold, a door, a becoming between two multiplicities’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 249). At times, particularly in his earlier work, Deleuze will even go so far as to suggest that the self is an ‘illusion’. For instance, in Difference and Repetition, he argues that ‘The modern world is one of simulacra … All identities are only simulated, produced as an optical “effect” by the more profound game [jeu] of difference and repetition’ (Deleuze 1994: 1, xix). Not just human identity, then, but any appearance of identity or self-sameness is taken to be just that, an appearance or by-product of a more fundamental processuality in which nothing repeats, or, rather, the only thing that repeats is differential (rather than bare) repetition itself.

However, in his work with Guattari, Deleuze frames the transcendent concept of ‘the Subject’ less as an illusion and more as an oppressive force operating at the level of the body and the social, as an organizing force that invites us to operate as if we were really separate from (and, in some cases, superior to) the other bodies populating the world. In A Thousand Plateaus, for example, Deleuze and Guattari characterize instances of subjectification as what they call ‘strata’: ‘acts of capture’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 40) or ‘phenomenon of sedimentation’ that impose organization and stasis on the otherwise mobile, material energy of the world (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 159). Alongside ‘the organism’ and ‘signifiance’, the subject is one of ‘the three great strata’, each of which attaches to a different aspect of life: the organism to the body, signifiance to the ‘soul’ (or unconscious) and subjectification to the conscious (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 160). The strata then come to coordinate our relationship to life, operating like a utilitarian logic or a transcendental point of view that passes moral judgement on differences from their respective representational categories:

You will be organized, you will be an organism, you will articulate your body – otherwise you’re just depraved. You will be signifier and signified, interpreter and interpreted – otherwise you’re just a deviant. You will be a subject, nailed down as one … otherwise you’re just a tramp. (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 159)

In contrast, Deleuze and Guattari argue that we need to ‘tear the conscious away from the subject in order to make it a means of exploration’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 160).

For now, a final way of understanding Deleuze’s immanence would be in relation to the scientific notions of ‘emergence’ and complexity theory. In 1969, while Deleuze and Guattari were working on Anti-Oedipus, Evelyn Fox Keller and Lee Segel published their seminal research on the behaviour of slime mould – a simple organism that nevertheless demonstrates highly complex behaviour. Now a classic example of ‘emergence’, Keller and Segel’s study of slime mould was one of the first specific accounts of what became known as ‘emergent systems’: systems that solve problems in a bottom-up rather than top-down manner, or immanently rather than transcendently (Johnson 2001: 14). As Steven Johnson among many others has discussed, slime mould has fascinated generations of scientists on account of its capacity for ‘coordinated group behaviour’ as well as its ability to oscillate between functioning as ‘thousands of distinct single-celled units’ and as a ‘swarm’ (Johnson 2001: 13). But whereas previously this behaviour was assumed to be coordinated by pacemaker cells, Keller and Segel found it to be a biological instance of leaderless organization and ‘decentralized thinking’ (Johnson 2001: 17).

In turn, many recent Deleuze scholars – from Brian Massumi to John Protevi and Manuel DeLanda – have emphasized the affinity between Deleuze’s work and the sciences of emergence. Protevi, for example, sees Deleuze as producing ‘the ontology of a world able to yield the results forthcoming in complexity theory’ (Protevi 2006: 19), while Massumi argues that Deleuze, along with Bergson and Spinoza, can be

profitably read together with recent theories of complexity and chaos. It is all a question of emergence, which is precisely the focus of the various science-derived theories that converge around the notion of self-organization (the spontaneous production of a level of reality having its own rules of formation and order of connection). (Massumi 2002b: 32)

And certainly, Deleuze’s emphasis on the processual and metamorphic nature of materiality constitutes a critique of hylomorphism: ‘the doctrine that production is the result of an … imposition of a transcendent form on a chaotic and/or passive matter’ (Protevi 2001: 8). In contrast, and thus in line with writing in the field of emergence, Deleuze’s thought ‘emphasizes the self-organizing properties of “matter-energy”’ (Marks 2006: 4), which Deleuze conceives of as the difference or line of variation running through all things.18 In this sense, one way in which Deleuze’s immanence manifests itself is as a specific understanding of how new forms are created, with an emphasis on the ways in which material bodies organize themselves rather than being construed as moulded into an organized form by an external force.

To have done with authors, directors and intention: Immanence in performance

Transferring such philosophical and scientific concepts of the distinction between immanence and transcendence to the domain of performance might enable us to generate contrasts between top-down and bottom-up tendencies in authorship, as well as to distinguish between different kinds of artistic organizations. Indee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Immanent Authorship: From the Living Theatre to Cage and Goat Island

- 2. Disorganizing Language, Voicing Minority: From Artaud to Carmelo Bene, Robert Wilson and Georges Lavaudant

- 3. Immanent Imitations, Animal Affects: From Hijikata Tatsumi to Marcus Coates

- 4. Paying Attention, Participating in the Whole: Allan Kaprow alongside Lygia Clark

- 5. Ethical Durations, Opening to Other Times: Returning to Goat Island with Wilson

- Conclusion: What ‘Good’ Is Immanent Theatre? Immanence as an Ethico-Aesthetic Value

- Coda

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index