- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Men and Masculinities in Irish Cinema

About this book

Spanning a broad trajectory, from the New Gaelic Man of post-independence Ireland to the slick urban gangsters of contemporary productions, this study traces a significant shift from idealistic images of Irish manhood to a much more diverse and gender-politically ambiguous range of male identities on the Irish screen.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Men and Masculinities in Irish Cinema by D. Ging in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

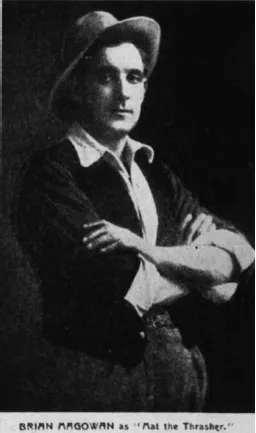

One of the earliest heroic male figures to appear in an Irish-made film was Mat ‘the Thrasher’ Donovan in Knocknagow (1918). Defined by his relationship to the land, Donovan exhibited strong sporting abilities, unfaltering self-discipline and a keen sense of community. Catholic and hard-working, he was untainted by modernity’s excesses and by the feminised, urban culture of Britain (see Figure 1.1). As such, he epitomised the New Gaelic Man of the early twentieth century. Fast-forward almost ninety years and we encounter a radically different range of male protagonists on the Irish screen: from Stuart Townsend’s slick, metrosexual Lothario in About Adam (see Figure 1.2) and Cillian Murphy’s troubled transvestite Patrick ‘Kitten’ Braden in Breakfast on Pluto (2005) to Colin Farrell’s laddish, underclass criminal Lehiff in Intermission. This book attempts to tell the story of how and why images of men in Irish cinema have changed so dramatically over the past century and, in doing so, maps out the changing historical relationship between nation, cinema, and masculinity in Ireland.

By and large, Irish cinema has been strikingly deficient in heroic men. Cinematic visions of Gaelic musclemen and swashbucklers do not readily spring to mind. We are more accustomed to images of men who are violent, tyrannical, emotionally damaged, depressed, suicidal, alcoholic, socially marginalised or otherwise excluded from the dividends of male cinematic heroism. Unlike many other mainstream national cinemas, which have – at least until recently – tended to treat heroic, patriarchal and patriotic masculinities as relatively unproblematic, most Irish filmmakers have been savagely critical of these paradigms and, since the emergence of what is known as the First Wave in the late 1970s/early 1980s, many of them have been engaged in a sustained and extraordinarily well-observed critique of the dysfunctioning of traditional patriarchy.

Figure 1.1 Matt ‘the Thrasher’ Donovan in Knocknagow (1918), Ireland’s first feature-length indigenous film: Gaelic manhood as selfless, spiritual and grounded

(Courtesy of the Irish Film Archive).

(Courtesy of the Irish Film Archive).

The early years of cinema in Ireland were characterised by foreign productions made in and about Ireland, a trend which persisted right up until the formation of the first Irish Film Board in 1980. As film historian Kevin Rockett (1996: i) points out, ‘more fiction films were produced about the Irish by American film-makers before 1915, when the first indigenous Irish fiction film was made, than in the whole hundred year history of fiction film-making in Ireland.’ Despite this, there was a moderately vibrant period of indigenous filmmaking during the silent era and, taken together, these films demonstrate some interesting similarities in terms of their construction of discourses around Irish manhood. Indeed, it is arguably only during this period that Irish cinema could be said to have engaged with a dominant, state-endorsed vision of Irish masculinity and Irish national identity. Thus, although an indigenous film industry was slow to develop and cinema did not play a key role in the construction of national identity, even the patchy filmic output of the first half of the twentieth century offers useful insights into emergent constructions of Irish manhood.

Figure 1.2 Fast-forward to 2000: Adam’s narcissism, materialism and urban lifestyle epitomise metrosexual masculinity in Gerry Stembridge’s About Adam (2000)

(Courtesy of Venus Film & TV Productions Ltd.)

(Courtesy of Venus Film & TV Productions Ltd.)

The handful of radically different visions of Irish manhood cited above demonstrate that masculinity is neither a monolithic nor a stable concept, that acceptable or dominant models of masculinity change over time and that, increasingly, different masculine types compete with one another for screen space. This should be obvious, when we consider how dramatically the acceptable codes and conventions of male identity construction have changed historically and differ from place to place: male homosexuality was acceptable in Roman times; high heels and make-up did not constitute a threat to aristocratic masculinity in seventeenth-century France; Mexican machismo is premised upon dominant sexual activity, irrespective of whether it occurs with men or women. As Connell (1995) has demonstrated, masculinities are ‘configurations of practice’ and must be understood within a broader framework of gender relations. However, although there are different manifestations of masculinity in any society at any given time (working-class, middle-class, gay, straight), each era has a hegemonic or dominant form, which attempts to legitimate male power and privilege. Although hegemonic masculinity in effect correlates to a very small minority of real men, and subordinated and marginalised masculinities do not necessarily benefit from the patriarchal dividend in the same way, they may still be complicit in the hegemony of patriarchy on account of the overall advantage to men of the subordination of women: ‘Masculinities constructed in ways that realise the patriarchal dividend, without the tensions or risks of being the frontline troops of patriarchy, are complicit in this sense’ (Connell, 1995: 79).

Both mainstream and art-house film have been to the fore in picking up on the radical, though often unnoticed, ways in which acceptable performances of masculinity change over relatively short periods of time. In this sense, films have much to say about how a particular society ‘does gender’ at different points in time. What characterises the hero of the classic western, the war movie or the action film is often emblematic of how that society has traditionally defined the ideal man, and much scholarly work on masculinity in cinema (Donald, 1992; Cohan and Hark, 1993; Kirkham and Thumim, 1993; Tasker, 1993; Smith, 1996; Spicer, 2001; Powrie, Davies and Babington, 2004; Pomerance and Gateward, 2005) has tended to focus on these dominant or traditional manifestations of manhood. According to Smith (1996: 88), this tendency to concentrate on images of the heroic male has effectively created a ‘monolithic view’ of masculinity in film studies, which disavows the multiplicity of masculinities or male subjectivities that populate mainstream cinema. However, even within the parameters of the debate on hegemonic masculinities in cinema, there is little consensus regarding the ideological functioning of the traditional male hero. Since the 1990s, both ontological and epistemological disturbances to the notion of an ‘unperturbed monolithic masculinity’ (Cohan and Hark, 1993: 3) have become increasingly evident in the diversity of cinematic masculinities available (Spicer, 2001) and in the variety of theoretical approaches being applied to their analysis.

What most of this research points to, therefore, is a much more complex discursive relationship between real and cinematic men than is implied by a simplistic cinema-as-social-mirror model. As we will see, for example, cinematic tropes of male disempowerment and victimhood do not necessarily signal patriarchal defeat; on the contrary they can be read as strategic attempts to reclaim agency and power through the representation of their loss (Savran, 1998; Carroll, 2011). Moreover, film production and distribution are complex, expensive, highly collaborative and market-driven processes. While it is rarely possible, particularly within the parameters of textual analysis, to take account of the multiplicity of factors determined by the wider contexts of production and consumption within which films circulate, it is nonetheless important to acknowledge that a natural, transparent or consistent relationship between what happens in ‘reality’ and the stories that get told on celluloid can never be assumed. Indeed, most films do not set out to represent the social world accurately: cinema is often as much about presenting a vision – be it utopian or dystopian – of how things could be as it is about commenting on how things are. Finally, it is crucial to note that no film industry, Hollywood included, is ideologically monolithic – indeed, cinema has also been adept at exploding the myths about hard men and in presenting us with alternative images of manhood, in the form of gay men, transgendered men, caring fathers and dedicated homemakers. As Rose Lucas (1998: 138–9) comments in relation to Australian cinema:

I would maintain that there is a necessarily intricate, even tangled, relationship between the production of ideology, or dominant social values as evidenced across a range of cultural experience, and the visual representations of the cinema. In this sense, images of masculinity in the cinema may indeed reflect and thus perpetuate dominant social ideas about masculinity; they may equally – and perhaps, at the same time – work to challenge and problematise those dominant representations.

In this sense, it is more useful to regard cinema not as a barometer of social experience but rather as a constituent part of the social world, an arena in which discourses are constructed and contested as well as merely represented. Indeed, as I argue in this book, films may collectively challenge the widely accepted take on a particular social reality and, as such, can provide a significant counter-discourse to the dominant or commonsense one. Thus, even if their relationship to dominant discourses is inconsistent or not directly representative, films offer us a nonetheless tangible set of images, themes and stories with which to grapple and, as such, are as viable an intervention into a topic such as masculinity as any other. Indeed, as this book seeks to demonstrate, their sometimes extraordinary capacity for picking up on issues that are unspoken or avoided in other discursive arenas makes their analysis in relation to masculinity especially fruitful.

In parallel with developments in scholarship on gender in cinema, masculinity has entered mainstream public debate, with the result that it is increasingly understood not as a monolithic entity but rather as a diverse and hybrid set of constantly changing modes of behaviour and identification. The past two decades have borne witness to important public debates about men’s roles in a changing society. This focus on men and masculinity has challenged the hitherto invisibility not only of male power and privilege but also of male suffering and anxiety, and it is primarily in the media that these new and often contradictory discourses on masculinity are being articulated and (re)negotiated. In Britain alone, the popular press has coined a plethora of new terms such as the New Man, the New Lad, Millennium Man, the Dad Lad, Metrosexual Man and Colditz Man (Beynon, 2002). However, as well as offering men and women ‘the culture’s dominant definitions of themselves’ (Gamman and Marshment, 1988: 2), mediated fictions also function as interventions into social discourses on the ‘genderscape’. Oftentimes, these discourses are confusing and contradictory: in the entertainment media, gangsters, criminals and hard men are enjoying a resurgence in popularity; yet a set of counter-discourses in the news media expresses a fear of deviant or antisocial male youth (Devlin, 2000) and of ‘men running wild’ (Beynon, 2002: 128).

Irish masculinities reflect much of this diversity, as this journey through Irish cinema will demonstrate. Related to all of the above developments but, in particular, to the influence of sub-genres from elsewhere, such as the British ‘underclass film’ (Monk, 1999) and the American ‘smart film’ (Sconce, 2002), is an increasingly ambiguous engagement with male-centred narratives, whose protagonists resist unequivocal ideological categorisation. In response to the polysemy that underpins postmodern culture, we are more inclined to re-read mainstream films and their representation of hegemonic masculinities as performative, as masking anxieties about powerlessness and failure and in terms of the fissures and slippages they fail to conceal. Thus, while traditionally, academic studies of masculinity in cinema have focussed on mainstream media texts’ perpetuation of dominant ideologies of gender (Donald, 1992; Hanke, 1998; Strate, 1992), there are a growing number of theorists who claim that, rather than presenting an ideologically coherent view of masculinity, the mainstream media are increasingly involved in contemporary society’s ‘troubling’ or problematisation of masculinity. Postmodern and post-feminist theorists, in particular, tend to view contemporary images of machismo not as reasserting or valorising hegemonic masculinity but rather as articulating anxieties about the impossibility and redundancy of the hypermasculine. In film studies, a number of influential theorists (Cohan and Hark, 1993; Tasker, 1993; Neale, 1983 and Smith, 1996) have argued that the hegemony of the heroic or hypermasculine male has always been underpinned by insecurities and contradictions. Cohan and Hark (1993: 3), for example, contend that ‘Hollywood film texts rarely efface the disturbances and slippages that result from putting men on screen as completely and as seamlessly as the culture – and the criticism – has assumed.’ It is in the context of these ontological and epistemological developments that this book has attempted to address Irish cinema’s recent moves toward liberal cosmopolitan cultural trends such as Lad Culture and New Mannism.

Underpinning this analysis as a whole is a concern not only with what films have had to say about and to understandings of Irish masculinities, but also with how these images and discourses appeal to and are used by their audiences. According to Michael Kimmel (1987: 20):

Images of gender in the media become texts on normative behaviour, one of many cultural shards we use to construct notions of masculinity.

Kimmel’s claim is instructive in that it acknowledges the powerful role played by mediated images in naturalising and reinforcing certain gendered behaviours, but also because it highlights media reception and identity construction as active, heterogenous and complex, as well as contingent upon a range of other contextual factors. In much of the literature on cinematic representations of masculinity, there are hidden assumptions about media effects, whereby it is implied that boys unquestioningly accept and emulate patriarchal role models. According to John Beynon (2002: 64):

… it is obvious that cinematic masculinity comes in visually crafted, carefully packaged and frequently idealized forms. These representations often have a more powerful impact than the flesh-and-blood men around the young and with whom they are in daily contact. Screen images are likely to be far more exciting and seductive than fathers, teachers, neighbours and older brothers.

While many screen images of masculinity are undoubtedly more appealing than real men, such claims tell us little about why such figures are appealing to audiences or how audiences situate their engagements with these images against the wider backdrops of their lives. Most importantly, they fail to qualify what is meant by ‘impact’. Empirical research that has considered how male audiences/consumers use mediated images as part of the social fabric of their daily lives (Robbins and Cohen, 1978; Walkerdine, 1986; Denski and Sholle, 1992; Fiske and Dawson, 1996; Lacey, 2002; Ging, 2005; 2007) has yielded rich – and often unexpected – insights, and should remind us that images, whether of unreconstructed hard men with an axe to grind or happy metrosexuals, offer different pleasures, identifications and fantasies to different viewers. Thus, for example, in her empirical study of The Sopranos’ British male audience, Lacey (2002: 101) revealed that the show gives men ‘a way into owning a drama and at the same time marking it as masculine TV territory’. Her findings indicated that middle-aged viewers in particular identified not with Tony’s power or the glamour of the mobster lifestyle but with the drudgeries of his life, and the pressures of trying to balance the emotional dramas of family life with his job. Lacey’s study thus supports Martha Nochimson’s (2002: 13) assertion that crime culture’s appeal may be less about violence and fantasies of male authority and more ‘a metaphor for the tangled desires of our daily lives’.

Similarly Fiske and Dawson’s (1996) study of homeless men watching Die Hard shows that their respondents sought out antisocial moments in the film, which they perceived as threatening the status quo (for example when the terrorists attack the corporation or the terrorists repel the police). However, as the hero became more closely aligned with the police force, the homeless spectators lost interest and even switched off the video. The researchers concluded that there are potentially antisocial moments within this predominantly prosocial film, which show subordinate groups and individuals winning tactical battles, if not the final victory and that, for these men, who take refuge in a Catholic shelter where their reading material is policed, ‘The ability to read antisocial meanings against a prosocial text is the equivalent of reading pornography under the cover of a respectable newspaper’ (ibid.: 306). Nevertheless, Fiske and Dawson (1996: 308) also make the important point that, ‘Representations of violence may well offer potentially progressive meanings in class or racial politics but repressive ones in those of gender’ (ibid.: 308). In the same vein, Lacey’s participants’ non-preferred readings are not automatically synonymous with ideological resistance: that they picked up on the masculinity-in-crisis subtext of The Sopranos may in fact signal little more than their prioritising of a more recent variant of hegemonic masculinity (the male as victim of feminism) over another, more traditional one.

Men again?

Over the past three decades, feminism, gender studies and queer studies have served to unravel and thus make visible the artificiality of the relationship between sex, gender and sexuality, with the result that men and masculinity have come increasingly under the spotlight. Culture, politics and history are no longer viewed as gender-neutral, and masculine identities are increasingly understood as socially constructed (Hearn, 1987; Horrocks, 1994; Kimmel, 1996). In spite of the apparent ‘constructedness’ of gender identity, however, most societies maintain a vested interest in ascribing fairly limited sets of gender traits to each sex. Change is slow and oftentimes highly contentious, since these processes almost always threaten to illuminate and thus undermine certain powers and privileges within the ‘genderscape’. When masculine norms are challenged, for example, by the dual threats of feminisation and objectification inherent in recent trends such as New Mannism and metrosexuality, there is very often a concerted effort both at the cultural and the political level to reaffirm a more traditional or robust concept of manhood. Such attempts generally rely on gender-essentialist notions of innate masculinity, which is deeply paradoxical given the fact that self-conscious efforts to revive traditional gender norms necessarily draw attention to the artificial and non-essential nature of this very process.

Thus, for example, in the 1990s, the mythopoetic strand of the American men’s movement drew on ancient myths in order to argue for a natural, pre-ordained gender order, in spite of the fact that these myths derived from a patriarchal, feudal past whose genderscape was no more natural than the present one. Similarly, while David Fincher’s film Fight Club ostensibly railed against narcissism, consumerism and homoeroticism, it used the most toned, manicured and sexually objectified male body in Hollywood to do so. As Robert Nye (2005: 1955–6) argues:

On its face, each episode of ‘remasculinisation’ we identify ought to undermine fatally the universalistic pretensions of a category so unstable that it must be wholly reconfigured every generation or so, but those of us who teach gender and sexuality know the subtle forms resistance to this conclusion can take, even within the age groups in our culture most disposed to flexibility.

What these subtle processes of ‘remasculinisation’ (Nye, ibid.) indicate is that there is a constant struggle over what constitutes normative or acceptable gendered behaviour in men, as well as over the meaning and implications of changes to this behaviour. For some theorists, the alleged ‘crisis i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Gender and Nation: the Gaelicisation of Irish Manhood

- 3 ‘Instruments of God’s Will’: Masculinity in Early Irish Film

- 4 Institutional Boys: Adolescent Masculinity and Coming of Age in Ireland’s ‘Architecture of Containment’1

- 5 Family Guys: Detonating the Irish Nuclear Family

- 6 It’s Good to Talk? Language, Loquaciousness and Silence Among Irish Cinema’s Men in Crisis

- 7 Troubled Bodies, Troubled Minds: Republicanism, Bromance and ‘House-Training’ the ‘Men of Violence’

- 8 New Lads or ‘Protest Masculinities’? Underclass, Criminal and Socially Marginalised Men in the Films of the 1990s and 2000s

- 9 Cool Hibernia: ‘New Men’, Metrosexuals, Celtic Soul and Queer Fellas

- 10 Conclusion: a Masculinity of ‘Transcendent’ Defeat?1

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index