- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the golden era of silent movies, stars have been described as screen gods, goddesses and idols. This is the story of how Olympus moved to Hollywood to divinise stars as Apollos and Venuses for the modern age, and defined a model of stardom that is still with us today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Film Stardom, Myth and Classicism by M. Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Charting the Firmament

1

Shadows of Desire: War, Youth and the Classical Vernacular

The first issue of British film fan-magazine Picturegoer, in October 1913, announced that ‘actual stars, and the greatest of these, of the dramatic firmament’ are being drawn to appear on the screen, as if they were moths to a silver sheet, or rather celestial beings projected before an audience at a planetarium. Despite the exclusivity of the language, the magazine’s readers are then invited to make their ‘“picture” acquaintance’ with these stars, already negotiating the balance of extraordinary and ordinary that characterises screen stardom1. In the same issue readers were alerted to the opening of The Carlton Theatre on London’s Tottenham Court Road. This ‘crimson carpeted Temple of White Marble’ was an early example of a wave of picture palaces from the 1910s to 1930s that provided comfort amid increasingly opulent architecture, often neo-classical, for exhibitors to draw larger middle-class audiences, who would have seen many of these actors on the (already culturally prestigious) stage, to worship the new screen gods2. ‘Playgoers’ will ‘become picturegoers’, the magazine concludes. At such screens that year fans might also experience what the magazine calls the ‘stupendous Italian productions’ of The Last Days of Pompeii (Mario Caserini), to which it devotes a main article, and the ‘great classical tragedy’ of Anthony and Cleopatra (Enrico Guazzoni), two of the many popular epics set in antiquity reaching an international audience in the 1910s, to which Hollywood would respond with ever-more expensive productions such as D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916). Through these small references we can see the promotion of cinema being subtly shaped by cultural discourses of the sometimes ancient past, and the stars of the firmament given a new home that rendered them as ethereal constructs of moving pictures, but paradoxically also producing a lasting record of otherwise ephemeral stage performances. Picturegoer’s announcement two weeks later that actress and courtesan Lillie Langtry had been signed to Famous Player’s ‘gallery of artists’ makes just such an assertion. Langtry is quoted, rather portentously, saying that appearing on film is ‘a distinction that will survive myself. Through its power of perpetuity, I am immortal – I am film!’3 Such aspirations to immortality, infused by the discourse of classical grandeur, were associated with many stars in the 1910s, when in the new age of mechanical reproduction, cinema promised to preserve the obsolescent performance for posterity, and somehow save its beauty from immanent loss, as if an animated form with the permanence and presence of sculpture. Again, a bi-focal temporal view is apparent. Cinema is both a wonder of modern technology, but in providing this art of immortality, it is bound to the past in its search for both a legitimising place in history, and in the venerated forms inherited therefrom.

It is this tension that the American Photoplay magazine addressed in two editorial prefaces from 1918 promoting cinema as a modern, yet traditional, art form. In ‘Art and Democracy’, we are presented with an illustration of two gallery visitors admiring a painting and a sculpture4. The text below relates how artists in ‘olden days’ used to survive on the benefaction of royalty, then a ‘wealthy merchant class’ imitated the aristocracy and ‘sought reflected glory by patronizing the arts’. At the end of the nineteenth century, the magazine continues, art was elitist in both subject and audience, and thus for the middle class and poor

there were only museums where they were permitted to see pictures and statues that they could not hope to own. In the very magnificence of the displays they were made to feel the more keenly the fact that this was not THEIR art, that it was not made for THEM.

Calling the moving picture the ‘first art-child of democracy’, Photoplay concludes with Lincolnian zeal that like the art of the old masters, Mozart or ‘Michael Angelo’, cinema ‘is an art of the people, for the people’. The magazine thus constructs cinema as the ultimate democratic form, not withstanding the slight aroma of cultural imperialism. There is also the irony, given the white temples, and their counterparts, springing up in the localities of the magazine’s readers, that while elitism was to be derided; the industry, apparently entering its classical period, was keen to place a big gilt and marble frame around its products often as magnificent as those in that museum of the past. Later that year in ‘The Eternal Picture’, the magazine reinforces its temporal thinking: ‘Pictures are not only ancient as logical thought; they are universal’, it opines with an archaeological reference to the value of images being discovered in the soil and sands of the world. ‘The motion picture is not really new’, the editor concludes, ‘It is a thing as old as the world, cast in a new mold. It is something more: it is the first and only amalgamation of science and art … [science] found the immemorial picture a changeless image – and gave it the breath of life’5. The motion picture, and by implication, the star, is here constructed as the apotheosis of artistic evolution, and particularly of classical antiquity. Not only that, but it also has the power to bring prestigious painting or sculptures of the past to life and immortality in the fashion of Langtry’s words and, once more, the Pygmalion myth to which I shall shortly turn.

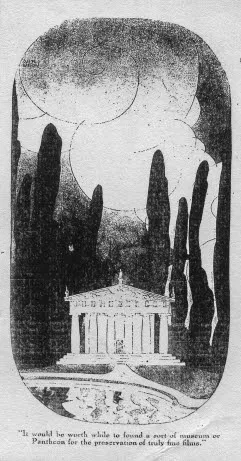

It is not hard to find similar statements of the cultural worth and power of the motion picture being proclaimed in the 1910s and early 1920s. In Britain, Picturegoer greeted the Italian production of Fabiola (Enrico Guazzoni, 1918) with the headline ‘Ancient Rome Lives Again!’, ‘It is as though twentieth century science had breached the gulf of years, lifting the veil for all of us to see’6. Photoplay returned to the theme in 1920. Claiming that ‘The Motion Picture in America is the most comprehensive movement toward a universal art-expression in several centuries’, again in slightly disingenuous genuflection towards ‘the great art of the Greeks [that] gave its form to every phase of Hellenic existence’7. Contemplating the ‘spiritual future’ of the movies in 1921, a feature penned by Nobel Prize-winning Belgian writer Maurice Maeterlinck visualised international cinema as muses in Greek dress attempting to break free from the shackles of industry depicted as a man in a suit cracking a whip. The essay even proposed the building of a ‘sort of museum or Pantheon’ within which to preserve ‘truly fine’ films that are ‘not inferior to many masterpieces of the past in literature, painting and sculpture’, an intriguing reference to the shrine of the old pagan gods which it illustrates as a shining white temple8. This image responds to Maeterlinck’s observation upon visiting America that its population held a ‘religious enthusiasm’ and ‘aspiration to something higher than material life’ which is partly served by films he views, with many exceptions, as often ‘tawdry’. Why is there such popular favour towards Hollywood, Maeterlinck asks, ‘[i]s it because it appeals to religious sentiments, because it insists on the necessity and benefits of Faith – without saying what sort of faith, and making faith appear superstitious, illusory and extremely dubitable?’9 This statement responds to both the question of why the people of America, and surely other nations too, need films, and therefore stars, and also why classicism, as a purely artistic vestige of a now-dead religion of antiquity, works so effectively to produce this secular pseudo-religion of film stardom. As a counterpart to Maeterlinck’s reverent Pantheon, writer Eugene Clement d’Art speculated in Picture-Play that the motion picture of the future would be exhibited in a form of giant cinema he names the ‘new Coliseum’, presenting a different classical model of perhaps less virtuous but equally spectacular occupation10. In Britain, too, fan-magazines presented cinema, often playfully, as if an extension of ancient Greek achievement. Picturegoer printed a comic verse in 1923 that joked about how far film has, or hasn’t, developed over the past decade, saying: ‘I thought that films would climb/The summit of Parnassus slopes/To join the arts sublime’11. An earlier feature, purportedly the ‘Confessions of a Kinema Star’, expressed this aspirational impulse more earnestly, asking rhetorically: ‘There’s something great in being in at the beginning of a great art, don’t you think?’. Comparing this time of cinema’s genesis and development to ‘looking on the first sculpture that was ever carved in ancient Greece’, the anonymous picture player concludes: ‘Whatever heights the “kinematograph” reaches – colour and all the other things – it can never begin again. We saw the start of it; and I think that is something great. Don’t you?’12 Film fans should consider themselves lucky, in other words, to be witness to the birth of another Golden Age. However, as is already very clear, cinema wasn’t exactly new at all, and neither were its stars (Figure 1.1).

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the theatrical parlance of the ‘star’ attraction back to 1779, gaining wider use from the 1820s, defining one who may also be a ‘person of brilliant reputation or talents’13. The term was already highly conducive to appropriation by cinema, which could technically and discursively elevate this figure in the limelight to the more elusive creatures of light and shadow beheld at the cinematograph. In Britain, a definition Picturegoer offered its readers in 1917 clearly looks to the media of the past in casting the star as a luminous being of the present while expressing the kind of existential uncertainty as to the exact nature of the star’s form and presence already noted:

We all know that a proper star is a luminous body in the heavens, and that it shines in the dark. A ‘star’ therefore became the chosen name that would most fittingly describe a person with brilliant abilities; a player, for instance, whose acting qualified him or her to shine on screen or stage … Thank goodness our film stars are no farther off than the picture screen of our favourite cinema14.

By the 1920s, M-G-M was gesturing to the stellar realm in declaring its famous legend that it had ‘more stars than there are in heaven’15. It is already clear that stars not only shine, but are enduring, and indeed, ‘immortal’; a statement of survival at a key point in history, as if a living work of art carving a passage through history. Thus, as fan-magazines suggest, in the new idols one also witnesses a return of the gods of antiquity, an idea that had also exercised the imagination of the Romantic poets. Discussing their use of classical imagery, Lawrence Kramer suggests that poets such as Keats gave ‘central places to a number of metonyms of divine presence, which embody the transfigurations that the gods would bring if they came’16. As I shall shortly argue, such returns had added resonance when, in the view of many – and supporting Maeterlinck’s view of Hollywood as secular religion – the Christian deity had apparently abandoned humanity amid the unprecedented devastation of the First World War. To further contextualise the way classicism was used to accentuate cinema’s looking forward and back, and indeed aspirationally ‘up’ to the future, we first need to turn back to observe the way the iconography and myth of antiquity has a long history of appropriation by those seeking both celebrity and political or cultural authority.

Figure 1.1 Illustration of Maurice Maeterlinck’s movie ‘Pantheon’, Photoplay April 1921

Iconography

Histories of Alexander the Great are also histories of the art of iconography, and indeed stardom, itself. It is thus not entirely facetious to see in Alexander the godhead of celebrity iconography. Studies of the history of fame reveal a figure who recognised the need to control his image in order to communicate his personal leadership across his empire, yet ensure this image was both clear and enigmatic. As Leo Braudy puts it, Alexander needed to make: ‘himself into someone to be talked about, interpreted, puzzled over, so that the mystery of his meaning would be as endless as his empire.’17 Like many cinema stars that have chosen one particular photographer to present them to their best advantage, such as Greta Garbo association with William Daniels, Alexander too favoured only the sculptor Lyssippos, painter Apelles, and Pyroteles the gem-carver18. Today, the ‘posed’ quality to Alexander’s statuary is striking, most pronounced in the slight turn of the neck and sometimes anguished expression, producing what Christine Mitchell Havelock describes as two distinct types, his ‘moral uprightness, his nobility, his Olympian calm on the one hand, and the transfigured, demonic, and inspired hero on the other’19. Apollo and Dionysus, perhaps, variously representing different periods of Alexander’s life and persona. Such poses also had the effect, Braudy notes, of fixing Alexander’s eyes ‘beyond the limited horizon of the person who looks at his representation’, and establishing a convention giving ‘many a solitary eminence the chance to be separated from the crowds but watched by them’20. Just as the stars of the silent era possessed this ordinary but extraordinary quality, and charismatic attachment to their present through the past, likewise Alexander’s fashioning of divine characteristics to further his image was ambiguous enough to exploit the religious beliefs of his times whi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Olympus Moves to Hollywood

- Part I: Charting the Firmament

- Part II: Flights to Antiquity

- Part III: Undying Pasts

- Conclusion: The End of the Golden Age?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index