eBook - ePub

Federalism and Decentralization in European Health and Social Care

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Federalism and Decentralization in European Health and Social Care

About this book

This is the first book to examine the processes of territorial federalization and decentralization of health systems in Europe drawing from an interdisciplinary economics, public policy and political science approach. It contains key theoretical and empirical features that allow an understanding of when health care decentralization is successful.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Federalism and Decentralization in European Health and Social Care by J. Costa-Font, S. Greer, J. Costa-Font,S. Greer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Health System Federalism and Decentralization: What Is It, Why Does It Happen, and What Does It Do?

Joan Costa-Font and Scott L. Greer

1. Introduction

Discussions of decentralization in health systems are ubiquitous, in politics and political economy, in economics, in health services, and in public policy. So is decentralization or territorial complexity in health policy and other areas of welfare responsibility, such as education and social care. It seems no country’s policy elites or scholars can quite stop debating the territorial organization of their government, public administration, and health services. They also decentralized more, starting in the 1970s in most cases. Its causes are much discussed, with diversity, democracy, and nationalism all playing clear roles (Hooghe et al. 2010; Loughlin et al. 2011; McEwen and Moreno 2005).

The rising tide of decentralization has major consequences for at least some health and social care systems (Saltman et al. 2007). Symbolically, it undermines the link between health, social citizenship, and the state (Greer 2009; Ferrera 2005). There is a strong tradition of thought that associates the state with citizenship, and which assumes that as both a practical and ethical matter, social citizenship rights such as health should be a national responsibility. From that point of view, any fragmentation of health services would be seen as privileging some at the expense of the rest, and hence would be unfair and unequal. However, the development of European integration and deepening of democracy unveiled differences in preferences and need, and the increasing perception of government inefficiency acted as a trigger for decentralization reforms; health care was a key one among them both in budget magnitude and strategic importance. More specifically, Besley and Kudamatsu (2006) argue that the correlation between health and democracy can be explained because they contend that democracies demand accountability to a broad set of citizens at regular intervals.

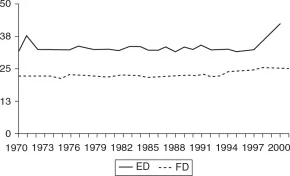

Figure 1.1 Expenditure and fiscal decentralization in the OECD (1970–2001)

Source: Stegarescu, 2005.

These patterns are complex; to speak of decentralization as if it were simple is to create confusion. Figure 1.1 shows that decentralization of expenditures (ED) is more prevalent than decentralization of fiscal revenues (FD), but looking at patterns there is a clear decentralization of patterns in OECD countries after the mid-1990s. More and more countries have been entrusting at least the management of health systems, if not their revenue raising, to regional and local governments (also Hooghe et al. 2010; Adolph et al. 2012).

Decentralization promises all sorts of things: to permit diversity and experimentation; to encourage learning and competition; to bring policymakers closer to the people so they are more informed and accountable; to coordinate and delegate; to get the central government out of the details of local policy; to engage people in decisions affecting their lives; to reflect territorial differentiation and afford stateless nations some self-determination. It is no wonder that it has appeared as a solution to all sorts of problems and it has been associated with all sorts of democratizing, modernizing, and budget-cutting policies. It can, in particular, be a way to rejuvenate and defend welfare states. Some economists have presented it as an alternative to privatization (Tanzi 2008). Unlike the privatization strategy that would lead to making use of market to complement or supplement what public healthcare systems provide, the decentralization strategy attempts to transfer health care and other responsibilities to subnational levels of government, creating as a result further veto power to attempts to wipe out public healthcare provision at a country level. This argument is consistent with evidence that decentralization does not lead to a “race to the bottom” (Costa-Font and Rico 2006) and if public entrepreneurs are scattered through the territory, decentralization can further public healthcare development (Costa-Font 2010a; Costa-Font et al. 2011). Political scientists are less likely to approach the choice of political institution as an optimization problem, but their many case studies of decentralization driven by an effort to enhance or defend welfare provision are consonant with this idea.

For all the importance of decentralization as a phenomenon, inquiry reveals that as a concept it is much too broad. It has almost no meaning on its own or that it can be invoked for almost anything, up to and including obviously centralizing policies within certain regional territories. More generally, decentralization proxies variables are as diverse as “regional autonomy”, “regional and local democracy”, and “veto points”.

2. The book’s mission

This publication both integrates and, we hope, clarifies this practically and theoretically confusing realm. It integrates across three divides: between economics and political science, between “federal” and other kinds of country, and between health and social care. It musters two disciplines – economics and political science – to map the past, present, and future of the territorial allocation of authority in the decentralized and big countries of Western Europe. It bridges between the different categories of state and terms such as “federal” or “devolution” that often obscure the interesting similarities and differences between Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, Nordic countries, and the UK. It thereby shows the ubiquity of territorial politics and the necessarily territorial nature of many health and social care policies. Finally, it incorporates social care as well as health. Social care is not just an understudied sibling of the healthcare system; it is also a key determinant of the workings of health care because its success or failure influences both the composition of need for health care and the fate of patients after their treatment is over. In ageing societies with increasing incidence of non-communicable and chronic diseases, the distinction between health and social care is increasingly difficult to maintain as a policy or an intellectual stance.

It clarifies, we hope, by stripping out assumptions that economists, political scientists, and practitioners have too often introduced into their analyses of decentralization and the allocation of authority in health. All too often, intriguing hypotheses with a germ of truth have been given more credit and power than they deserve, whether it is the old Jacobin hypothesis that centralized states deliver equality and prevent corruption or the Tiebout hypothesis that decentralization forces local governments to compete away their services (Chapter 2). Instead, it brings to the fore both theoretical discussion from second-generation fiscal federalism and new politics of the welfare state, alongside empirical evidence both quantitative and qualitative of different European countries that differ widely in institutional design and historical inertias.

This introduction frames the theoretical and empirical chapters by stating the key questions that are often begged or ignored: what does decentralization mean, why does it happen, and what are its effects? It then briefly reviews the book, highlighting lessons from the theories reviewed in Chapter 2 and the country studies.

3. The allocation of authority in health care

There is a great deal of received wisdom about decentralization, much of it the half-remembered remains of debates about the territorial organization of one country or another, or overenthusiastic application of intuitive but limited hypotheses. Unfortunately, much of it is contradictory, dated, limited, or even possibly wrong and often does a disservice to the authors who formulated the original ideas. The second chapter shows how both economics and political science have handled the causes and effects of decentralization. The territorial politics of health is a terminologically and intellectually complicated area hosting multiple disciplines, approaches, and nationally specific discourses. “Decentralization” can be a slippery topic that encompasses topics as diverse as constitutional change in the UK and re-centralization of planning in Norway (see relevant chapters in the book). This chapter presents our shared questions.

We define decentralization as a change in the allocation of authority in which powers shift to smaller territorial units of government. We argue for agnosticism about the causes and consequences of decentralization. There are plenty of explanations and intuitions, and functionalist interpretations, but many go beyond their data. This book, starting with a clear focus on the territorial allocation of authority, helps bring out the plausibility and limits of different causes and consequences.

3.1. What does decentralization mean?

As mentioned above, the very meaning of decentralization is a cause of no little confusion. Much of the problem lies in the continuing use of a framework developed by a World Bank economist in the early 1980s that incorporated almost every form of administrative change into the definition of “decentralization” including, most notably, privatization as well as more conventional territorial definitions (Rondinelli 1981, 1983). This definition creates a remarkable level of confusion: simply put, creating a Scottish Parliament, selling British Telecom, and moving the drivers’ license agency out of London are three profoundly different kinds of actions, and lumping them together does not make them easier to understand (Lemieux 2001). Only in the crude perspective of early-1980s neoliberal economics could they be seen as meaningfully similar in causes, mechanisms, or consequences (Exworthy and Greener 2008; Peckham et al. 2007).

It is not hard to define decentralization more meaningfully. The first important statement about decentralization is that it is territorial. It means shifting the territorial level of organization of some power or another, altering the allocation of territorial authority by giving rise to some expansion of regional autonomy, and more specifically a regional political agency (Besley 2006). This means that it excludes de-concentration (moving government offices around) as well as other kinds of administrative reform, such as privatization or New Public Management. Governments committed to such other reforms have sometimes also embraced decentralization, but there is no necessary link between decentralization and any other kind of reform. For every case of decentralization coupled with neoliberal management reforms in this book, there is one in which it went with expansion of the welfare state (e.g. Spain) or an effort to democratize public administration (e.g. France), and the epitome of new public management, the UK under Thatcher and Major, was also the epitome of territorial and political centralization (Bulpitt 1983). The territorial allocation of authority is the object of study here.

The key subordinate distinction for many purposes is that between elected and unelected general governments. Territorial politics and territorial issues are ubiquitous, of course. Population characteristics including demographics, economies, and health needs all vary territorially. As a consequence every government policy has some territories that get more than others: money spent on teaching hospitals rewards areas with those (usually big old cities), while money spent on rural primary care does nothing for cities. This automatically means that territorial politics always has a distributive component: taxpayers are funding programs and policies that have different effects in different places. But those distributive decisions can be made more or less visible and political. Heterogeneity can be accommodated rather than set aside. Greater visibility for territorial differences, in the case of health and social care, can have many effects. It can trigger further healthcare development and innovation if political credit can be traced to regional incumbents. But, as Chapter 2 explains, soft budget constraints can be particularly pervasive in the case of health care because it is unlikely that the central government will not bail out regions that fail to meet their budgetary commitments (Crivelli et al. 2010).

Chapter 2 presents the work of economists and political scientists on the conditions for the various outcomes, stressing how institutional design can shape them. But one finding that is rare in territorial politics literature shapes the data, health systems, and health policies of the countries we study. That is the distinction between National Health Service systems, where taxation finances a state-dominated system, and social insurance systems where legislation shapes semi-public insurance carriers. National Health Service systems in decentralized countries, such as Italy, Spain, Norway, and the UK, tend to be decentralized to the major level of local or regional government (e.g. regions in Italy, Spain, and the UK, or local government in Scandinavia). In social insurance systems, whether centralized or decentralized, the health finance system and the organization of health care are separated from regional governments, as in France where the state’s use of regional health agencies is quite separate from elected regional governments, or in federal Germany, whose constitutional court went so far as to declare the logic of territory alien to the logic of social insurance (see the chapter by Mätzke). The reasons for this difference – the apparent propensity to decentralize National Health Service systems – remain as unexplored as the difference is unremarked. It could be a strategy to democratize, to harness competition, to spread blame, or just a response to the expectations and veto players found in social insurance systems.

3.2. Why do countries decentralize?

For all the debates about decentralization and the allocation of authority, there is remarkably little structured attention to territorial politics and territorial political change: it can be extraordinarily difficult to identify the responsibilities of tiers of government within a country, let alone to explain how they got that way.

The dominant mode of discussing centralization and decentralization in health is technocratic. It argues the costs and benefits of a particular allocation of authority: will services be more efficient, innovative or responsive, or cheaper if they are run by a particular level of government? We see it in every article about centralization or decentralization that simply takes governments at their word about the functional benefits of a particular allocation of authority (Costa-Font 2010b), or that argue for one change or another on grounds of good health services.

The problem is when these functional justifications are taken as explanations of the decision. Decentralization might produce better health policies in the UK or Spain, but a cursory look at those countries’ histories suggests that health policy did not motivate devolution or furthering regional autonomy, but the demands lie in the political arena instead. At most, it was one of many issues that contributed to a sense among leaders of the stateless nations that they should have more autonomy (Gr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- 1. Health System Federalism and Decentralization: What Is It, Why Does It Happen, and What Does It Do?

- Part I: Background

- Part II: Cross-Country Evidence in Tax-Funded Health Systems

- Part III: Cross-Country Evidence in Social Insurance Systems

- Index