- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

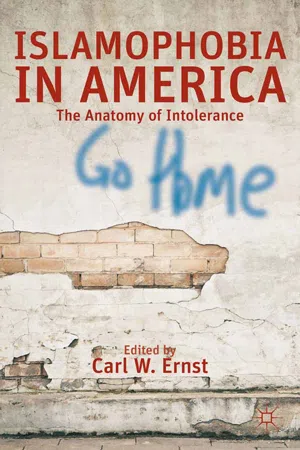

Islamophobia in America offers new perspectives on prejudice against Muslims, which has become increasingly widespread in the USA in the past decade. The contributors document the history of anti-Islamic sentiment in American culture, the scope of organized anti-Muslim propaganda, and the institutionalization of this kind of intolerance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Islamophobia in America by C. Ernst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Common Heritage, Uncommon Fear

Islamophobia in the United States and British India, 1687–1947

Peter Gottschalk and Gabriel Greenberg

When confronted with the commonality of Islamophobic themes of the fanatic Muslim man, the oppressed Muslim woman, and an intolerant Islamic religion, defenders of these views often respond that their prevalence must reflect their truth. After all, they argue, all stereotypes have some seed of truth. The ironclad quality of this tautology—that past repetition of an allegation is justification for its reiteration—recommends a different tack in refutation. A historical evaluation of these claims that demonstrates their persistence despite historical changes helps demonstrate how the core of American and British Islamophobia derives from received truisms that have established—and continue to establish—basic expectations about how Muslims behave. These expectations shape how information about Muslims is interpreted so that what fails to fit within this frame of reference (e.g., Muslim tolerance, nonviolent Muslim protest) often is overlooked.

If a Mohammedan, Turk, Egyptian, Syrian or African commits a crime the newspaper reports do not tell us that it was committed by a Turk, an Egyptian, a Syrian or an African, but by a Mohammedan. If an Irishman, an Italian, a Spaniard or a German commits a crime in the United States we do not say that it was committed by a Catholic, a Methodist or a Baptist, nor even a Christian; we designate the man by his nationality.1

Perhaps, the only thing that exceeds the accuracy of Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb’s observation is the surprise that this New Yorker made it more than a century ago. Such a comment would not seem out of place in the United States or Great Britain following the attacks of 9/11 and 7/7. Americans and Britons have struggled not only with domestic Islamist violence but also with the question of how to respond, in terms of both national defense and community engagement. Since the 2001 attacks, non-Muslim Americans have crowded classrooms to learn about Islam, churches and synagogues have invited Muslim speakers to conversations, and mosques and Muslim organizations have heightened interfaith outreach. Nevertheless, Muslims have continued to suffer heightened suspicion in both countries, drawing worried looks, enduring invasive scrutiny, and even being removed from airliners. But the fact that Webb’s criticism—too often, even if decreasingly, appropriate in the United States and the United Kingdom of today—dates from so long ago demonstrates that Anglo-American Islamophobia is not new.

A historical exploration of British and American literature between 1690 and 1947 demonstrates the roots and qualities of Islamophobia that Britons and Americans have shared. Meanwhile, significant differences between the perspectives found in the two countries demonstrate how these were fashioned by differing concerns about their own societies. In order to emphasize this difference, we choose to compare American views of Muslims with those found among Britons who had lived in India. In the latter context, predominantly white Christian Britons found themselves a minority in a land once ruled by successive Muslim rulers who left impressive vestiges of their once-mighty empires. As a ruling elite, Britons had to adapt their Islamophobic inheritance to the exigencies of governing tens of millions of Muslims. In the United States, engagements with Muslims appeared to be a matter of international affairs alone, “Mohammedans” representing an “other” far more distant than the Jews, Catholics, and other religious minorities who lived among the Protestant majority.

Before beginning, we need to outline the parameters of this study. First, by “Islamophobia,” we refer to a largely unwarranted social anxiety about Islam and Muslims. Much more could be said about British and American stereotypes about Muslims. Other groups have also suffered negative stereotypes in these societies, but few communities have been perceived as so threatening. Hence, our argument here focuses only on the features of Muslims that have evoked such fear among the majority without exploring many of the other accusations about Muslims—such as their misogyny, their opposition to modernity, their commitment to a sensual religion, and their association with specific races. Other essays in this collection deal with these important issues, as does our previous work.2

Second, some might argue that American concerns about certain threats (e.g., the Barbary pirates) did not focus on Islam at all. We agree that in certain confrontations, American representations may have fixed primarily on the supposed race, ethnicity, and/or nation of an antagonistic group that happened to be Muslim. However, even such depictions almost invariably included Islamophobic inflections that proved Islam to be a damning quality of that group. For instance, the Barbary pirates might be “Arabs” but that included—if it was not exacerbated by—the unfortunate quality of being Muslim as well. Meanwhile, missionary literature continually reinforced the supposedly inherent conflict between Islam and Christianity. Third, we note that a focus on British perspectives in India should not suggest that South Asians did not have their own views, that they did not differ from Britons’, or that they simply subsumed their understandings to British ones. Earlier scholarship has demonstrated the significant and changing dynamics of interaction and representation between many of the myriad groups of the subcontinent both preceeding and during British rule. However, our particular endeavor to track the shared heritage and divergent expressions of Anglo-American Islamophobia mandates the exclusion of these voices.

The Anglo-American Heritage

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, no one influenced British and American attitudes toward Islam more than Humphrey Prideaux. In 1697, this Anglican theologian published his seminal book on the topic, The True Nature of Imposture Fully Display’d in the Life of Mahomet. The book’s popularity led to eight editions in 25 years with copies finding their way to the American colonies as early as 1746.3 Although the volume’s central thesis—that a self-serving Muhammad intentionally deceived his followers by masquerading as a prophet—had long existed in Europe, his work made the allegation commonplace.4 Originally, Prideaux sought to write a history of Constantinople’s fall but, overwhelmed by a concern for what he perceived as British indifference to religion led him to narrate Muhammad’s biography instead. The author highlighted the so-called prophet’s fraud, tyranny, and fanaticism5 in order to demonstrate the qualities of a real impostor and counter deist claims of Christianity’s imposture.6 Indeed, a section addressing deist claims took up half the original book’s length. By the end of the eighteenth century, two American publishers released new editions to an audience shaped by revolution and religious schisms both at home and in France. The publisher of the second American edition sought to address the twin hazards of centralized government and oppressing dissent and omitted altogether the section devoted to the deist “apostacy” that so motivated Prideaux. To the editor, John Adams was the real threat, a modern Muhammad.7 Thus, the same denigrations of Muhammad were adapted to critique different Anglo-American situations over the course of a century.

Continental views also influenced British and American perspectives. The French philosophe Voltaire intended his 1742 play, Le fanatisme ou Mahomet le Prophete, as both a warning against religious intolerance and praise of secular humanism. Clergyman James Miller translated Voltaire’s work into English in a manner that supported the secular humanism theme while using the image of the lust-filled Mahomet to criticize fanaticism and the abuse of power. In England, it was reprinted annually between 1745 and 1777, while the play premiered in New York and Philadelphia in 1780 and 1796, respectively.8

These two early examples demonstrate three significant dimensions of Anglo-American Islamophobia that would be rehearsed repeatedly over succeeding centuries. First, depictions of Muslims—and of the final Islamic prophet in particular—often served as a foil serving social critiques of British and American domestic issues entirely unconnected to Islam. Just in the various editions of the two influential examples noted above, depictions of Muhammad’s life aided endeavors to warn Britons and Americans against deism, federalism, political tyranny, religious apathy, and religious zealotry.

Second, the perception of Muslims and Islam as a threat pervaded so broadly that even the most ardent secularists and Christians (these groups were not mutually exclusive) could utilize them as foils serving quite divergent agendas. Prideaux saw Islam as the anti-Christian product of a power-hungry imposter. Voltaire viewed Muhammad’s excesses as a warning to governments that espoused religion. As we shall see, secularists like Thomas Jefferson often included Muslims as an extreme example marking the lengths to which toleration should be practiced. Simultaneously, Christians often viewed Islam as—if not the greatest threat to Christianity—the largest obstacle to its universal expansion.

The third and final dimension of Anglo-American Islamophobia demonstrated by the example of Prideaux and Voltaire’s works is how certain lines of communication facilitated the transcontinental transmission of Islamophobic ideas. Given the popular authority of those with personal experience of Muslims and the British empire’s involvement with Muslim communities across the world, information and opinions often flowed westward across the Atlantic. Clearly, Britain and the other European powers with a stake in North America contributed the seeds for the first sad blossoms of Islamophobia there. This current continued through the next century as evidenced in a variety of ways by the American Charles Godfrey Leland. In 1874, he concluded his satirical travelogue by quoting an article from London’s Daily Telegraph.

We are very glad to announce that the annual pilgrimage to Mecca has gone off this year with remarkable success. “Glad to announce!” we hear good Mrs. Grundy ejaculate; “why should a Christian newspaper rejoice over the happy conduct and term...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Problem of Islamophobia

- 1 Common Heritage, Uncommon Fear: Islamophobia in the United States and British India, 1687–1947

- 2 Islamophobia and American History: Religious Stereotyping and Out-grouping of Muslims in the United States

- 3 The Black Muslim Scare of the Twentieth Century: The History of State Islamophobia and Its Post-9/11 Variations

- 4 Center Stage: Gendered Islamophobia and Muslim Women

- 5 Attack of the Islamophobes: Religious War (and Peace) in Arab/Muslim Detroit

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index