- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The current economic crisis has presented itself as a formidable challenge to the welfare states of Europe. It is more relevant than ever to ask: do existing minimum income protection schemes succeed in adequately protecting citizens, be it whether they are excluded from work, working, retired, or having children? Drawing on in-depth and up-to-date institutional data from across Europe and the US, this volume details the reality of minimum income protection policies over time. Including contributions from leading scholars in the field, each chapter provides a systematic cross-national analysis of minimum income protection policies, developing concrete policy guidance on an issue at the heart of the European debate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Minimum Income Protection in Flux by I. Marx, K. Nelson, I. Marx,K. Nelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A New Dawn for Minimum Income Protection?

1.1 Introduction

In May 2009, the European Parliament called on the Commission and the Member States ‘to guarantee the right to a minimum income irrespective of individuals’ chances in the labour market’. In its Resolution, the Parliament made reference to an almost 20-year-old European Council Recommendation that recognized ‘the basic right of a person to sufficient resources and social assistance to live in a manner compatible with human dignity’. Some months earlier, in a Recommendation on the active inclusion of people excluded from the labour market, the European Commission (2008) had already stated that the ‘Council Recommendation 92/441/EEC of 24 June 1992 on common criteria concerning sufficient resources and social assistance in social protection systems remains a reference instrument for Community policy in relation to poverty and social exclusion and has lost none of its relevance, although more needs to be done to implement it fully’.

The re-emergence of the 1992 Recommendation in European Union policy discourse, after having lingered in relative obscurity for almost two decades, is as remarkable as it is important. This reappearance of minimum income protection is not only evident at the European level, but it has also taken place in several member states, be it to varying degrees. Thus we start this introductory chapter by setting out why the subject of minimum income protection is more topical than ever, and why we believe that legitimately to be the case. We then move on to provide a short overview of existing research on minimum income protection, setting the scene for this book and what it contributes.

1.2 Minimum income protection and the EU agenda for social inclusion

It would seem self-evident to put the re-emergence of minimum income protection on the EU agenda in the context of the economic crisis we have been witnessing for the past couple of years. This is undoubtedly true. Yet we believe it is probably more accurate to say that the economic crisis sharpened an already emerging awareness of the crucial role social safety nets play in providing adequate protection when markets fail to do so. Clearly, even before the crisis that awareness was growing. Paradoxically, perhaps, this was not because things were bad, but because they were so extraordinarily good. The years prior to the crisis had brought strong employment growth in many countries and unemployment rates had reached levels not seen in decades. Yet relative poverty rates had hardly budged. In some countries poverty had actually increased.

1.2.1 Blooming labour markets and poverty standstill

The rise in employment levels in the period preceding the financial crisis which started in 2007 had not come by accident. In most EU countries a marked policy shift had taken place towards boosting labour market participation levels and reducing benefit dependency among those at working age. The increased emphasis on supply-oriented labour market policy took a drastic turn in some countries. It also involved social protection reform (Kenworthy, 2011). The German so-called Hartz reforms are perhaps one of the most prominent examples of this restructuring of social protection. Unemployment assistance (Arbeitslosenhilfe) and social assistance (Sozialhilfe) was abolished and replaced by a new benefit (Arbeitslosengeld II). In this reorganization of social protection it was mainly the middle tier of the system of unemployment benefits that was subject to the most extensive cutbacks. The new benefit corresponded more closely with the lower rates of social assistance than with those of the former unemployment assistance benefit (Eichhorst, Gienberger-Zingerle and Konle-Seidl, 2008). However, since its introduction, Arbeitslosengeld II has fallen short of general income growth, while poverty among recipients has increased (Kuivalainen and Nelson, 2011).

The shift from passive programmes to policies that more directly aim to increase labour supply had started already in the 1990s with the advent of such doctrines as the Third Way in Britain and the Active Welfare State in Belgium. When the Lisbon Agenda was agreed at the turn of the new millennium, the idea of employment growth and poverty alleviation as natural and inseparable allies had become central to policy reform in most if not all EU member states. Active approaches to social protection also applied to EU social cohesion policy. Central to the Lisbon Agenda, and particularly to its execution, was the creation of new employment opportunities. This underpinning was quite effectively summarized in the title of the Kok (2003) report on a revised European employment strategy: ‘Jobs, jobs, jobs’. This renewed belief in the possibilities for social development fostered by full employment proved not altogether illusory. Just prior to the crisis, unemployment rates had dropped to historically low levels in many countries. In some countries the unemployment rate was far below levels that observers only a decade earlier deemed impossible to achieve (OECD, 1994). Spectacular success stories came to dominate the academic and political agenda, the ‘Dutch Miracle’ being one example. Yet it also became increasingly clear that employment growth had not produced the expected outcomes in terms of poverty reduction. Marked increases in employment rates had been accompanied with rising or stagnant poverty rates for the working aged population. The Lisbon Strategy proved unsuccessful in the fight against poverty (Cantillon, 2011).

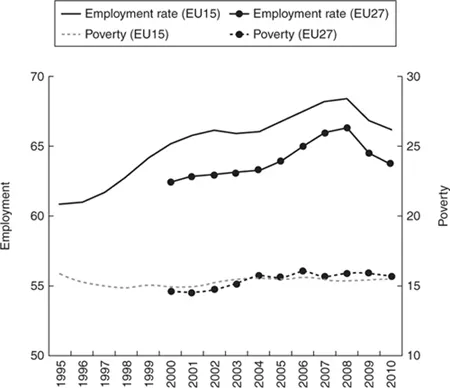

Figure 1.1 shows the poverty and employment rates as averages for the EU countries 1995–2010. Here we use the EU at-risk-of-poverty rate corresponding to the share of individuals below 65 years that live in households with incomes below 60 per cent of the median disposable income. All income is measured after adjustments for household size and composition. The employment rate is for the population aged 15–64. The increase of employment is quite evident. Between 1995 and 2008 the employment rate increased on average by about 8 percentage points in the EU15. For all EU member states we only have data from 2000 and onwards. In this larger group of countries the increase in employment was particularly pronounced in the mid-2000s. For our purposes it is particularly interesting and relevant to note that the increase in employment is not followed by a corresponding decline in the relative income poverty rate. In fact, the poverty rate has been fairly stable over the period, fluctuating around 15 per cent in the EU15 and towards the end of the period being at a slightly higher level in the EU27.

Figure 1.1 Poverty and employment rates in the EU countries, 1995–2010

Note: The poverty threshold is 60 per cent of the equivalized median household disposable income. The poverty rate is for the population less than 65 years. The employment rate is for the population aged 15–64.

Source: Eurostat.

The distributive outcomes of the welfare state are often due to a number of interrelated factors, such as the organization of social protection, the functioning of labour markets and demographic patterns. We can see at least two principal reasons why job growth has failed to reduce poverty levels in Europe. The first observation is that employment growth did not sufficiently benefit individuals and families in the lower tail of the income distribution. In countries where job growth did take place, the new labour market opportunities mostly went to young people, women and other groups who were entering the labour market for the first time. In some countries job growth was of such magnitude that it was theoretically big enough to provide every unemployed person with a job. Nonetheless, dependency on the welfare state remained in some instances stubbornly high, the Netherlands being one example (Marx, 2007). Another factor of relevance for the limited success of job growth in poverty reduction terms is that having a job does not necessarily imply a life free from financial poverty. The combination of strong employment growth and stagnant poverty heightened awareness to an issue that was not new but that became more poignant: the issue of in-work poverty (Andreβ and Lohmann, 2008; Crettaz, 2011; Fraser, Gutiérrez and Peña-Casas, 2011; Marx and Nolan, 2012).

1.2.2 Minimum income protection and the OMC

Effective poverty reduction and increased social cohesion require more than job growth and employment income. Minimum income protection also has an indispensable role to play, for non-active people and workers alike. While some scholars have been arguing that the social dimension of European integration would prompt governments to adopt some common denominators (Threlfall, 2003), tangible results on European policy convergence or harmonization in the area of social protection is unclear at best. In terms of social insurance replacement rates and social assistance benefit levels, quite the opposite development of cross-national divergence has been observed (Montanari, Nelson and Palme, 2008; Nelson, 2008).

These enduring institutional differences in national frameworks for social protection are to some extent surprising, not the least when focus is on minimum income protection. It is true that the social dimension of European integration has for many years been a contested topic (Hantrais, 2007). In part due to the difficulties of countries coming to agreements on binding legislatives, the Lisbon Agenda included a new EU initiative to foster social integration, focusing on the diffusion of ideas and best practices. Within the framework of the Open Method of Coordination (OMC), the member states agreed on common objectives and indicators against which national and EU developments could be evaluated and compared (Atkinson et al., 2002). The intention was and remains to assist the member states to identify good examples, which can be used nationally to develop new ways to tackle the issues of poverty and social exclusion. The protection of minimum incomes is integral to the social dimension of the OMC. The prominence of minimum income protection for European social policymaking is visible in the portfolio of indicators for the monitoring of the European strategy for social protection and social inclusion (European Commission, 2009). Social assistance is the only benefit scheme that enters this list and the proposed indicator is the level of non-contributory and means-tested minimum income benefits as percentage of the EU at-risk-of-poverty threshold for three types of jobless households. The impact of this policy indicator for measuring social progress in the various member states has so far been modest. One reason is of course that the data is still under preparation, although some progress has been made on the basis of tax and benefit model simulations developed jointly by the European Commission and the OECD.

The disappointing outcomes of the Lisbon Strategy in the social sphere have raised the demand for more interventionist approaches to tackle the issues of poverty and social exclusion. It was in this context that renewed references appeared to the European Council Recommendation on common principles for the organization of minimum income benefits in the EU member states. These principles included extended coverage, differentiated benefit amounts and formal indexation procedures. The exact governance structures were, however, not detailed. As such, countries were free to define the level of benefits by their own terms. Similarly, it was up to the member states themselves to judge how benefits levels should reflect household size and composition, and how benefits should be updated. The 1992 recommendation on minimum income benefits, originally drafted as an EU Directive but later downgraded to an EU Recommendation, followed the logic of soft governance that characterizes EU policymaking in the social domain. Instead of direct legal intervention and harmonization of national policy, in the early 1990s the EU started to promote social policy coordination by means of policy advice and guidelines. The shift that has appeared in EU governance since 1992, where coordination by objectives rather than means has become the guiding principle, makes this renewed interest for policy advice and guidelines in EU rhetoric on social policy matters somewhat remarkable. Whether or not the re-emergence of the 1992 Recommendation on minimum income benefits is a response to the failure of the Lisbon Strategy to produce improved poverty outcomes is beyond this introductory chapter to explore. Nonetheless, it is evident that this new blend of objectives and means in the steering of the European social inclusion process coincides with the advent of the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy, which has replaced the Lisbon Strategy as major framework for EU economic and social development.

1.2.3 Europe 2020

The Europe 2020 Growth Strategy, which details the approach for European economic development over the years 2010–20, would appear to mark a further step of European social integration (Marlier, Natali and Van Dam, 2010). The new strategy includes seven flagship initiatives, and the European platform against poverty and social exclusion is of most relevance for this volume on minimum income protection. According to the headline target for this flagship initiative, the member states are committed to raise at least 20 million people from the risk of poverty and social exclusion by 2020.

The idea that employment growth and poverty reduction need to go together remains at the core of the Europe 2020 Agenda, but there seems to be an implicit recognition now that higher levels of employment may not automatically bring better social inclusion outcomes. For example, the European Commission (2010) recently stated that social protection is an additional cornerstone of an effective policy to combat poverty and social exclusion in Europe, complementing the effects of growth and employment. Within this framework, social benefits should not only provide the right incentives to work, but also guarantee adequate income support (European Council, 2011). The concept of ‘income adequacy’ is of course ambiguous. Nonetheless, the European Parliament (2009) has defined the term as an income level at least on par with the at-risk-of-poverty threshold agreed by the EU member states. Programmes designed to provide minimum incomes, such as non-contributory and means-tested benefits, play a crucial role in fulfilling this objective. The centrality of minimum income protection for European social development is also notable in the Social Protection Committee’s (2011) assessment of the social dimension of the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy, where it is stated that member states should reinforce minimum income safety nets by expanding coverage and increasing benefit levels in regions where policies are weak. The role of the Social Protection Committee is to foster cooperative exchange between member states and the European Commission in the OMC framework on social inclusion.

The reality of inadequate safety nets really hit home when an economic downturn of a magnitude unseen in decades struck in 2007. Despite some differences between individual countries, unemployment levels generally surged, causing among other things an increased demand for income protection.

In several European countries the financial crisis implied a descent into financial hardship for many families. In this light, a more thorough and perhaps even more critical review of social protection and minimum income benefits seems urgently needed. This is where this book is aiming to make a contribution. The first duty of any welfare state worthy of that name is arguably to provide minimum safety nets that are able to rescue from poverty all those who fail to be provided by the market or first-tier contributory benefits. These minimum income benefits enter the distributive process when all other programmes have failed. Next we provide a review of the state of comparative research on minimum income benefits. Sometimes we refer to the term ‘minimum income protection’, which usually denotes the whole package of benefits received by families without work income and access to contribut...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 A New Dawn for Minimum Income Protection?

- 2 Struggle for Life: Social Assistance Benefits, 1992–2009

- 3 Mind the Gap: Net Incomes of Minimum Wage Workers in the EU and the US

- 4 Child Poverty as a Government Priority: Child Benefit Packages for Working Families, 1992–2009

- 5 Minimum Income Protection for Europe’s Elderly: What and How Much has been Guaranteed during the 2000s?

- 6 From Universalism to Selectivity: Old Wine in New Bottles for Child Benefits in Europe and Other Countries

- 7 Categorical Differentiation in the Light of Deservingness Perceptions: Institutional Structures of Minimum Income Protection for Immigrants and for the Disabled

- 8 Origin and Genesis of Activation Policies in ‘Old’ Europe: Towards a Balanced Approach?

- 9 Social Assistance Governance in Europe: Towards a Multilevel Perspective

- 10 Minimum Social Protection in the CEE/CIS Countries: The Failure of a Model

- 11 The EU and Minimum Income Protection: Clarifying the Policy Conundrum

- Index