eBook - ePub

The Field of Eurocracy

Mapping EU Actors and Professionals

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Field of Eurocracy

Mapping EU Actors and Professionals

About this book

The word Eurocracy has resonance throughout out Europe but in reality we know little about the people who work in and around the EU or how they fit into its large bureaucratic framework. Based on extensive fieldwork, this book addresses this problem by exploring the MEPs, diplomats, civil servants and commissioners that work in and around the EU.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Field of Eurocracy by D. Georgakakis, J. Rowell, D. Georgakakis,J. Rowell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

MEPs: Towards a Specialization of European Political Work?

Willy Beauvallet and Sébastien Michon

Introduction

The degree of Europeanization of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) is a central bone of contention between inter-governmentalists and supra-nationalists in European Studies (Schimmelfeinnig and Rittberger, 2006).1 The debate dates back to the normative arguments put forward by neo-functionalist theorists who claimed that the direct election of MEPs would produce a body of professionals dedicated to the promotion of the Community and its parliament (Haas, 1958; Cotta, 1984). From this perspective, European socialization, through membership in the institution, is perceived as a process of loyalty transfer from the national level to the European level. Other studies contest the evolutionist perspectives implied by spill-over theories. They underline the permanence of national ties and the ineffectiveness of spill-over in structural terms (no emergence of a European public or political space), ideological terms (no significant conversions to Europe) or sociological terms (no identifiable European political class). These scholars emphasize the pre-eminence of nationally centered political careers and the heterogeneity of national processes of selecting representatives (Reif and Schmitt, 1980) and of practices of representation (Navarro, 2009), as well as the lack of interest from representatives who are mostly nationally minded – as measured by their high resignation rates (Bryder, 1998). Accordingly, the importance of the internal socialization processes of the European Parliament (EP) is downplayed. The evidence of the pro-European position of many MEPs is ascribed to an effect of selection processes within national parties rather than to a conversion resulting from direct involvement in European institutions (Scarrow and Franklin, 1999; Scully, 2005).

These studies provide an alternative to the predictive and normative postures that are still present in the academic literature on the European Union (Hix et al., 2005). However, there are two limitations. First, these studies neglect the effects of closure linked to institutional construction. Numerous studies published since the 1990s have shown the specialization and rationalization of parliamentary work following the transformation of institutional configurations brought about by the succession of treaties since 1986 (Bowler and Farrel, 1995; Delwit et al., 1999; Costa, 2001). For instance, Hix and Lord (1997) document a shift from an ‘exogenous’ political system (based on external considerations and constraints) to an ‘endogenous’ one (based on considerations and constraints determined by the imperatives and specificities of internal factors). From a neo-institutionalist perspective based on a rational choice approach, Kreppel (2002) highlights the establishment of a ‘supranational party system’ influenced by external forces, and in which actors develop strategies and use their organization skills to respond to these evolutions. The second limitation of these studies – and of others inspired by neo-functionalism and neo-institutionalism – is their lack of sociological depth. On the one hand, they neglect the effects of social and political trajectories on the forms of investment and the choices made by the actors in situ. The approach is too often descriptive and fails to use social and political biographies to put into perspective preferences and practices (votes, number of questions asked, parliamentary reports and so on). On the other hand, they tend to disregard the consequences of the transformation of the MEPs’ profiles since the first direct election of 1979. These are significant, if not revolutionary, transformations. Verzichelli and Edinger (2005) have, for example, analyzed the constitution of a ‘critical mass of EU representatives,’ but have pointed out the permanence of the centrifugal forces limiting the autonomization and differentiation of a specifically European elite.

This chapter aims at going beyond the often-normative dilemmas inherent to these debates. It adopts a political sociology approach (Georgakakis, 2009; Georgakakis and Weisbein, 2010) and, more precisely, an approach labeled as structural constructivism (Kauppi, 2003). This entails studying Europe as a growing space of power, rather than as a system or a regime (Hix, 1999; Magnette, 2003a; Quermonne, 2005) resulting from economic, legal and ideological spill-over or as a mere bargaining arena controlled by member states (Moravcsik, 1998). In order to analyze the EP’s institutionalization, we will mobilize tools from the ‘sociology of the state’ (Weber, 1959; Elias, 1991; Georgakakis and Weisbein, 2010). Along these lines, we will conceptualize the differentiation of this space as the result of multiple processes of accumulation and concentration of specific resources as an often unexpected or undesired effect of the competitive cooperation between various actors (European and national civil servants, political representatives, members of interest groups and so on) who strive to increase their own capacities for action and decision making.

Structural constructivism emphasizes three complementary elements: first, the importance of the processes through which certain resources (‘capital’) are concentrated and redefined at the European level (Georgakakis and De Lassalle, 2007a; Rowell and Mangenot, 2010); second, the emergence of new ‘breeds’ of political professionals in charge of individual and collective political enterprises aimed at appropriating specific resources, whose management requires increasingly specialized knowledge and skills (Georgakakis, 2002a); third, the existence of specific socialization processes promoting shared values, skills and cultures that limit access to a field of power (Georgakakis, 2004b; International Organization, 2005; Michel and Robert, 2010). By combining these elements, we can study the invention of a European political and institutional order that is both partly differentiated from and interdependent with national spaces – a situation which has been termed a ‘multi-level political field’ (Kauppi, 2005).

The institutionalization of the EP needs to be put into perspective with the emergence of a new category of specialists in political work (Beauvallet and Michon, 2010b). This European professionalization is the product of social and political processes and not the result of ideological choices or a mechanical effect of new legal rules or treaty provisions (Beauvallet, 2007). The peripheral position of the EP in national political spaces makes it less attractive to political elites than many national political mandates. This situation has, in turn, favored more open recruitment, with the investiture of actors who are less endowed with the most legitimate national political resources. For a growing number of actors, the EP represents an opportunity to professionalize and acquire political capital, especially as the increasing importance of the EP within the European institutional triangle has helped make investment in parliamentary work more rewarding. Together with institutional and political evolutions, these socio-political transformations favor the emergence of actors who are more directly specialized in European affairs and are able to accumulate and concentrate enough internal resources to hold leading positions in the field of Eurocracy.

The persistent turnover of parliamentary personnel and heterogeneity of MEPs linked to its multinational character and the variety of procedures to select candidates and electoral systems are, therefore, partly compensated for by internal dynamics restricting access to the European field, the clearest manifestation of which is the strong specialization of leadership positions within the EP.

In order to test these hypotheses, we have built a biographical database of elected MEPs of the sixth EP (2004–9), with data collected from the official institutional list (n=785).2 Beyond the national logics and the strong heterogeneity inherent in a multinational population, the first section will aim at showing how their social and political recruitment have nonetheless tended to converge. The second section underlines the emergence of a parliamentary elite: that is, specifically European in terms of resources and career types, likely to occupy the main leadership positions within the EP.

The transformation and specialization of MEP recruitment

By studying MEP profiles, we can observe a degree of convergence of socio-demographic and political characteristics and a growing average length of seniority. The EP appears as a privileged space of political investment for political personnel climbing up the political ladder. One can identify a Europeanization of selection processes: that is, the emergence of explicit and codified norms, which apply to various national contexts. The differences in profiles between MEPs from countries of the 2004 and 2007 enlargements and the other countries confirm this hypothesis: the former, recently subjected to European norms, are close to MEPs of the 1980s in terms of social and career characteristics.

The underlying convergence of socio-demographic characteristics

The EP is increasingly considered to be an area of political professionalization for a predominantly middle-aged, well-educated and partly internationalized and feminized elite. Professional backgrounds tend to reflect those of the general political personnel (Best and Cotta, 2004). MEPs come from the middle or upper-middle-classes, with a predominance of lawyers and academics (Hix and Lord, 1997; Norris and Franklin, 1997), who adapted to the field of Eurocracy that, as a whole, has historically favored law and expert competence (Vauchez, 2008a). The high level of the degrees obtained by MEPs confirms their intellectual profiles. For example, in the sixth EP, 81 percent held a university degree, and 27 percent had completed a PhD. MEPs from accession countries tend to be more academically qualified, and more often have studied economics, science and technology and health than law and the humanities. They are more likely to have been active in scientific professions, as top civil servants or in the diplomatic corps than have their counterparts from older member states (see Table 1.1).

Through the increasing internationalization of elites and academic markets (Wagner, 1998), MEPs increasingly have international profiles. In the sixth EP, 12 percent had obtained a degree in a country other than their own (elsewhere in Europe, in the United States or even in Russia for some East European MEPs). Smaller countries with a relatively peripheral position in the EU are, not surprisingly, over-represented in this regard: Hungary, the Czech Republic, Malta, but also Portugal and Greece. Going across borders and attending prestigious universities abroad allows elites from ‘small’ countries to receive the same training as future elites from ‘big’ countries, allowing those from small countries to acquire resources that can be converted in both national and European spaces.

In terms of age, European representatives are, again, not much different from other political professions: most are middle aged (Best and Cotta, 2004). In 2007, their mean age was 53.8 years (standard deviation of 10.1 years) – the oldest being 83, whereas the youngest was 24, and the modal age class was between 50 and 60 (40 percent of MEPs). This situation results from a long-term evolution. In 1979, the European political profile was older: the notion of the ‘end-of-career’ MEP prevailed. During the late 1990s, it was the opposite; most MEPs (73 percent) were aged between 40 and 60 and 14 percent were under 40, whereas 13 percent were over 60 (Hix and Lord, 1997). Variations among countries need to be pointed out: Luxembourg, Cyprus and Estonia had high average ages (over 60), followed by France and Italy (56 and 57 respectively), while Bulgarian, Hungarian, Maltese and Romanian MEPs were under 50 on average.3 Generally speaking, MEPs from left-of-center political groups tended to be younger (52 for the Greens/European Free Alliance (EFA) and for the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL), compared to an average of 55 for the European Popular Party (EPP), and 57 for the Independence/Democracy Group (ID). Female MEPs were, on average, three years younger than their male counterparts (respectively 52 and 55).

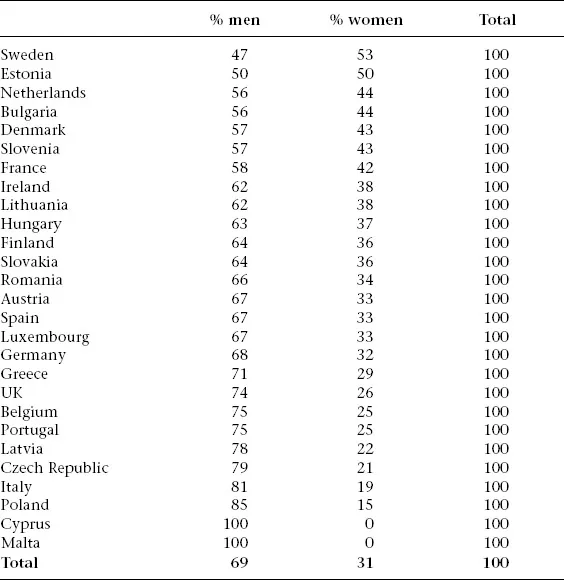

The proportion of women, higher than in most national parliaments, doubled between 1979 and the last two EPs: 16 percent in 1979, 31 percent in 2004 and 35 percent in 2009. If the EP is one of the most feminized parliaments in Europe (Kauppi, 1999; Beauvallet and Michon, 2008), it has not yet achieved gender parity. Major variations remain among countries, indicating important differences among national political systems. There are few female MEPs from Cyprus, Malta, Poland, Italy, the Czech Republic and Latvia. Women are better represented in Sweden – the only country where parity is achieved – and in the Netherlands, Denmark, Estonia, Slovenia and France, where more than 40 percent of MEPs are women (Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Distribution of occupation and degree levels in the sixth EP

Table 1.2 Gender distribution in the sixth EP depending on country of election (in descending order)

All in all, the MEPs from countries of the 2004 and 2007 enlargement are less feminized than those from the original 15 EU members (28 percent against 32 percent, respectively) and there are more women in center-left groups (Norris and Franklin, 1997) – Party of the European Socialists group (PES), 40 percent of MEPs, 47 percent for the Greens/EFA – than in the GUE, 31 percent, EPP, 28 percent, and especially the ID, Union for Europe of the Nations (UEN) and non-attached, between 11 percent and 16 percent. Generally speaking, the EP provides opportunities for political profes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Studying Eurocracy as a Bureaucratic Field

- 1 MEPs: Towards a Specialization of European Political Work?

- 2 Tensions within Eurocracy: A Socio-morphological Perspective

- 3 The Permanent Representatives to the EU: Going Native in the European Field?

- 4 ECB Leaders. A New European Monetary Elite?

- 5 The World of European Information: The Institutional and Relational Genesis of the EU Public Sphere

- 6 Expert Groups in the Field of Eurocracy

- 7 Interest Groups and Lobbyists in the European Political Space: The Permanent Eurocrats

- 8 The Personnel of the European Trade Union Confederation: Specifically European Types of Capital?

- 9 European Business Leaders. A Focus on the Upper Layers of the European Field Power

- Conclusion: The Field of Eurocracy: A New Map for New Research Horizons

- References

- Index of Names

- Index of Institutions and Concepts