![]()

Part I

Introduction and Background

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The presidency is unquestionably the central institution in the American government. The president and vice president are the only two officials elected by the nation as a whole. The media focuses attention on the office and person as well as his or her friends, family, and advisers. There is not as much attention paid to substantive activities, such as policy and governance. We as a nation look to the president for leadership.

This makes the American presidency a highly individualistic office and institution. The individuals elected to it or who ascend to the office very much determine the shape and functioning of the second branch of government. These individuals influence the parameters of the office for those who follow. The overall theme of this work will be the effects that individuals who occupy the office of president have on the institution—for both them and their successors.

Background and Constitutional Roots

The current institution of the American presidency has developed predominantly since the 1930s. The look, the duties, and the behavior we attribute to American presidents is not what one might expect from a reading of the Constitution or of the accounts of those who met in Philadelphia in 1787. The Framers were ambivalent toward the office of president and the duties and powers that should be assigned to it. Naturally, after having just fought a war for independence against what they had felt was a tyrannical monarch, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were leery of a singular executive office with vast powers. As a result, the Constitution says little about the scope of the presidency as a key concern on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the powers for the legislative branch, while being sufficiently vague to allow room for future adaptability, are rather well laid out.

The Articles of Confederation, the first document detailing the structure, duties, and powers of the government, delineated no real executive power. The executive was viewed predominantly as a chief administrator whose responsibility was to ensure the day-to-day functioning of government. All real national governmental power rested with the Congress. Soon after the adoption of the articles, however, it became clear that the new nation would have some difficulty functioning, perhaps even surviving, if some stronger powers were not ceded to the central government. Under the Articles of Confederation, most power really was left to the states. This set of circumstances led to competing policies on interstate trade, the minting of money, and the ability to quell public disturbances (e.g., Shays’s Rebellion).

This early view of federalism made arbitration between states and central coordination of activity difficult, to say the least. Many states would coin their own money and impose tariffs on goods crossing their borders from other states. Voluntary contribution of revenue by the states to the central government made national budgeting often unsteady and filled with the unexpected. Such uncertainty in the revenue process also made it difficult for the new nation to repay debts it incurred during the war against Great Britain.

The Constitutional Convention was called, in part, to resolve these weaknesses. As with the compromises that shaped the structure of the national government and the powers given to it, the powers given to the presidency were also a compromise. Specifically, this compromise was between those who sought great powers for the office and those who did not wish to see a powerful executive. The delegates did consider the possibility of an executive by committee because of their fear of monarchy, but soon discarded the concept as unworkable.

It was delegate James Wilson of Pennsylvania who delineated powers for the chief executive based on the powers granted to governors in the New York and Massachusetts State Constitutions. Those powers had been based in the philosophies of John Locke and Baron de Montesquieu, who both saw the need for a singular office to which the responsibility for the execution of the laws would go. Montesquieu, in particular, seems to have been the driving force behind the concept of separation of powers and the creation of a strong executive with limits on its powers. Much less frequently discussed are a number of philosophers who may have influenced the Framers. In his detailed intellectual and philosophical history of The American Presidency, Forrest McDonald (1994) wonderfully depicts many of these thinkers and their beliefs. In particular, the work of Jean-Louis De Lolme on the English Constitution is enlightening and has a familiar ring to it. De Lolme, naturally, is referring to the King when he discusses “the executive,” but describes many of the powers of the central government that would emerge from the Constitutional Convention and specifically the very powers the Framers would assign to the executive. Much of the debate, however, centered around two views or models of the executive: the weak executive model and the strong executive model.

In the weak executive model, the executive would be chosen by the Congress for a limited term of office. He (historically speaking) would serve at the pleasure of the Congress—much like a prime minister in a parliamentary system of governance. It would be the chief task of the executive to carry out the will of the legislative branch and serve mostly an administrative function. All war and treaty powers would be reserved to the legislature and there would be no executive veto of legislative action. In some versions of this model, the executive was conceived of as an executive by committee (Madison 1787).

The strong executive model, in contrast, would be independent of Congress. In this view of the executive branch, there would most certainly be a single individual to occupy the office and carry out the duties. The Congress would have only limited power to remove the president and, similarly, there would be limited ability by the legislature to control the actions of the executive. Any council (i.e., a cabinet) would be advisory in nature and would serve solely at the will of the executive.

As with most aspects and provisions of the new governing document, the end result was a compromise. In this case, however, the final structure more closely resembled the strong executive model. The difference was that the Framers had created a potentially strong institution that would share power with the other elected branch of government—the legislature. Perhaps, the single greatest achievement of the delegates at that convention was to create the system of checks and balances, or as Madison put it, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition” (Madison 1788). Throughout our history, we have seen one branch of government check the overreaching of another or two branches working together to prevent one branch from so totally dominating the political process that democracy is frustrated entirely. The common sense of the deliberative process prevented the overtly partisan actions of some in the legislative branch from reaching fruition. In the cases of the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and William Jefferson Clinton, the more statesmanlike tone and the deliberation in the Senate thwarted the efforts of the House. In the case of Richard Nixon’s abuse of power, the investigative powers of the Senate, the impeachment power of the House, and the power and prestige of the Supreme Court (and in the end, Nixon’s ability to see the inevitable) saved the nation from perhaps its most grave constitutional crisis since the Civil War.

What Are the President’s Duties and Powers?

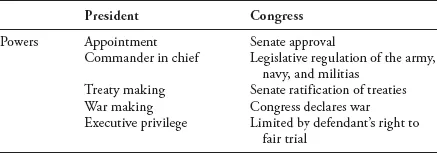

Article II of the Constitution delineates not only the most basic process of selecting the president, but it also lays out the duties and powers granted to the executive. Once again, though we often use terms like “powers granted,” it is more often the case that the powers are held in check by some limiting power held by either Congress or the courts. Naturally, there are some powers held by each of the three branches that are exclusive to that branch. See table 1.1 for a list of powers held by the president and the powers of other branches that can check those powers.

More often than not, we as a society refer to the president as “the commander-in-chief.” While this is a direct quote from the constitution and seems to be a rather traditional view of the presidency, it is a somewhat misleading statement. The constitution actually states that “the president shall be Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.” This wording must be taken in its actual context. As we will see throughout our discussion, the presidency has changed over the two hundred plus years of our nation’s history. It has grown in scope, relevance, and political (if not legal or constitutional) power. When the founders wrote those words in 1787, the armed forces of the United States consisted of the various state militias—the organizations we today think of as the National Guard. So, at least in the infancy of our nation and of the institution of the presidency, the president was commander in chief of very little. This is not the image we have of our contemporary president in command of millions1 of fighting men and women and the technological marvels they use to defend our national interests.

Table 1.1 Examples of presidential powers checked by powers of other branches

We usually think of the legislative process as one involving only those we elect to the US House of Representatives and the Senate. The president is, in reality, a key player in the process. Some scholars have referred to the president as the nation’s chief legislator (see e.g., Stephen Wayne’s Legislative Presidency 1978). Most students of American government and politics, even if only at the high school level, are aware of the president’s power to veto2 legislation passed by both chambers of Congress. The president’s legislative duties, functions, and abilities are not limited solely to the veto, however.

In addition to the more well-known power of the veto, the president has a number of other powers that relate to the legislative process. The president may recommend legislation to Congress and may “from time-to-time” address the Congress with respect to the state of the union.3 Most presidents in the twentieth century used this vehicle to lay out their legislative agenda for the coming year. Another power exists where the two chambers cannot agree about when to adjourn; the president may adjourn the legislature. More importantly, and not used very often in recent history, is the president’s power to convene extraordinary or special sessions of Congress to deal with pressing national matters. Perhaps, the most effective use of this power to achieve a political end was when Harry Truman called the Republican controlled Congress into session in August of 1948 for a two-week special session. The Republicans in the legislature refused to act on the proposals Truman sent to them and Truman then campaigned against the “do-nothing Congress.”

Presidents influence public policy in a number of ways outside of the legislative arena. Obviously, as the principal foreign policy officer of the nation, the president has a great deal of influence over our relations with other countries. It is not only through personal visits or the pronouncement of policy under the scrutiny of the press or in the halls of the United Nations that he or she may do so, but also through the negotiation of treaties with foreign leaders. Such agreements must be approved or ratified by two-thirds of the US Senate.4 With each new administration come many appointments to key positions in government, among some of the most important of these are our ambassadors to other countries. Who the president selects to represent both our nation and him- or herself affects how we interact with other players in the arena of world politics. It is rare that a presidential nominee for an ambassadorship is rejected by the Senate. Presidents also have the power to receive ambassadors from foreign powers and it is usually carried out in a rather routine fashion. New nations seek out this exchange as a measure of legitimacy among the players on the world political scene.

Similarly, the president has available the appointment of a great many positions in the executive branch. These individuals range from the White House chief of staff to cabinet secretaries to other lower-level political appointees. All of the highest-ranking appointees must be confirmed by the Senate, but the president may make sole appointments of “such inferior officers” as granted by Congress. All of these individuals have significant influence over the development and implementation of public policy of all kinds, whether it is the terms of a nuclear arms treaty or workplace safety specifications promulgated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. If a president selects the wrong individual for one of these posts it could spell disaster for the president’s position on the policy or for the administration itself. Presidents have been placed in the position of requesting the resignation of key administration appointees or having to dismiss them outright because of an appointee’s deviation from the president’s position, failure to implement policy in accordance with the president’s wishes, overzealousness, and other offenses.

Perhaps, the highest profile appointments any president can make, and they are such because of the potential long-term impacts on public policy and interpretation of the law, are those to the US Supreme Court. Additionally, presidents also make appointments to the lower levels of the federal court system, but none garner the level of attention, scrutiny, and potential opposition as those to the Supreme Court. All federal court appointments are for life and while this term of office makes it difficult for judges to fall victim to the whims of politics, it also means that once confirmed their impact on public policy can be quite long lasting. More youthful appointees to the federal bench can have influence on law and policy making for many decades before they retire or pass away. Presidents can use this fact to their advantage in attempting to ensure their own lasting impact on policy beyond their maximum term (for more on presidential appointment strategies and qualifications of judges see chapter 16).

Continuing in this vein, presidents have more powers of a quasi-judicial nature. Just as we are all well aware of the powers that state governors have to grant reprieves and pardons, so too does the president have similar powers. We may even recall old movies where the convicted criminal awaits the last minute phone call from the governor pardoning him for his crimes. While rarely as dramatic, the president has a similar power with respect to those convicted of federal crimes. Usually, such grants on the part of the president are not very controversial, but on occasion they do stir some conflict. The most recent example of such controversy was the last minute pardons by Bill Clinton5 as he prepared to turn over power to George W. Bush in January of 2001. Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon was certainly controversial and served to undermine the initial public goodwill enjoyed by the Ford administration.

As many students of American government and politics are well aware, Congress has among its grant of powers something called “the elastic clause” or “the necessary and proper clause” to provide room for it to stretch its reach or expand its explicit powers.6 Some have argued that the oath of office that all presidents must take upon their ascension contains a particular phrase that provides much the same flexibility or elasticity given to Congress. All presidents must swear that they will “faithfully execute the office of President.” Some have argued that this phrase provides the “wiggle room” necessary for presidents to implement some laws in a way that the original authors of the law might not agree as their intent. Thus, a vaguely written law may give the president vast room in which to maneuver.

Limitations on Executive Power

It cannot be stressed enough that presidents, or for that matter any branch of government, cannot act alone. Presidents have little ability to act unilaterally. They need a majority of both houses of Congress to pass legislation; they need approval of the Senate to make many appointments, and they cannot raise revenues by simple executive order. Even in an era when we have conducted many significant military actions (some more the equivalent of war and others as “peacekeepers”), without a constitutional declaration of war by Congress, presidents cannot unilaterally wage war. They are constrained by congressional budgetary authority, international law, the War Powers Act, judicial review,7 and public opinion.

So, not only is presidential action constrained by the normal system of checks and balances, which gives the power of the purse to Congress, the ability to declare war to Congress, confirmation of appointees to the Senate, and the power to impeach to Congress, but it is also constrained by the actions of other nations and by the American people. In addition, unlike parliamentary systems of government where the political executive is a member of and elected together with the legislature, the United States has a separate election of the executive. This is relevant to our discussion of limitations on executive power because a prime minister in a parliamentary system can, by definition, almost always count on the support of a majority of the legislature to support his or her programs. Here, even when the president’s party is the majority in the legislative body, there is sufficient interbranch rivalry to make it impossible to count on party support in all cases. Certainly, recent presidents can attest to this fact, but more so for recent Democratic presidents. Jimmy Carter had no easy time achieving a majority for his legislative agenda and though Bill Clinton had much greater success in his first two years when he had a partisan majority, he suffered some major setbacks due to the actions of his own party in Congress.

Birthers, Qualifications, ...