![]()

Part I

Global University Rankings: History, Concepts and International Developments

![]()

1

Introduction: University Rankings and European Higher Education

Tero Erkkilä

Introduction

Global university rankings have existed for only a decade and yet they have received unprecedented attention from higher education policy experts and scholars, as well as from politicians and the general public (Cheng and Liu, 2006, 2007; Erkkilä and Kauppi, 2010; Hazelkorn, 2008; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Salmi and Saroyan, 2007; Salmi, 2009). Previous analyses of global university rankings have concentrated on the methodology they use and their social effects from the perspective of efficiency and quality assurance (Dehon, Vermandele and Jacobs, 2009; Shin, Toutkoushian and Teichler, 2011), their impacts on higher education institutions (HEIs) (Hazelkorn, 2011) and their ability to reshape the higher education landscape in terms of its diversity (Kehm and Stensaker, 2009). There are also studies on the global governance of higher education that identify university rankings as one of its elements (King, 2010; Shin and Kehm, 2013).

This book provides a detailed analysis of rankings as policy instruments of global governance, but unlike the other analyses, we contextualize our investigation by looking at the institutional outcomes of the use of rankings in Europe, both at the EU level and at national level. We concentrate primarily on the political challenges, policy shifts and institutional results that the rankings precipitate. The situation of European higher education shows that the rankings do not acknowledge different institutional traditions and that the policy reactions and institutional responses differ contextually. Moreover, the authors draw attention to the role of institutional traditions in channeling and absorbing the changes that have taken place. In offering a critical approach, this study argues firmly for diversity in higher education, highlighting the limitations and unintended consequences of governance through ranking.

At present, there is growing concern over the academic performance of European HEIs in light of global university rankings that portray European universities as faring poorly by international comparison, with only a few exceptions. The top HEIs in the United States (US) enjoy higher rankings. This has been damaging for Europe’s self-image as the historical home of the university institution (Ridder-Symoens, 2003a, 2003b; Rüegg, 2004, 2010). The above discrepancy has also contributed to the reshaping of higher education policies in Europe. European nation states still have differing national discourses regarding academic institutions and their reform, which reflects the relatively limited extent of international regulation in the realm of higher education. However, the construction of a European policy problem of academic performance has marked a start for institutional reforms in Europe, often drawing its insights from global narratives on higher education (Schofer and Meyer, 2005) as echoed by the university rankings.

We examine the challenges for European higher education in the context of global governance, including perceptions in the US and Asia. The global rankings have geographic implications, as they produce rankings not only of universities but indirectly also of countries and regions, revealing differences among them. They render institutional traditions visible, making, for instance, the European university model a policy concern for the European Union (EU). The rankings are also increasingly policy relevant. They have helped create a political imaginary of competition, where European universities have to be reformed if they are to be successful. There are several ongoing reforms in the domain of higher education in Europe that refer to the university rankings when identifying states of affairs that demand action.

Regarding the notions of reform, the rankings increasingly provide an ideational input for higher education policies at the EU level, as well as at national and institutional levels. Indeed, the organizations producing the league tables have come to steer decision making while possessing no apparent norm-giving authority. Some scholars have likened this reflexivity to a Foucauldian compliance with received norms, now portrayed by the rankings (Erkkilä and Piironen, 2009; Löwenheim, 2008). Moreover, the new political imaginary of competition as an influence on the policy choices of domestic policy actors may become so captivating that they no longer perceive other options beyond this policy discourse.

However, we should not overemphasize the impacts of the rankings, as there are several ongoing policy initiatives that work in the same direction, such as the Bologna process (Schriewer, 2009). It is therefore challenging to identify the actual effects of rankings in themselves. Global policy scripts (Meyer et al., 1997) tend to take different forms when implemented at national level and may lead to layering of old and new institutional forms, or even an outright conversion of institutional practices. The national institutional traditions therefore have the ability to buffer or channel the institutional impacts of policy scripts, such as rankings (see Chapter 5 of this volume).

We will therefore analyze the use of global university rankings as policy instruments, focusing on the policy concerns that they have triggered in Europe. Furthermore, we will assess the ranking’s potential effects on higher education policies, institutions and disciplinarity. These transformations strive for competition and excellence in higher education but may also lead to an increasing economism, institutional uniformity and susceptibility to unintended consequences.*

Global university rankings

Given the prominence that the global university rankings enjoy in the media coverage of higher education, it is striking that such league tables have been in existence for only ten years. The first Shanghai ranking was published in 2003, followed by the publication of the Times Higher Education Supplement (THES) ranking in 2004. University rankings have existed in the Anglo-American countries for a longer time, but only at a national level. The first US evaluations of graduate programs started already in the 1920s, and a ranking of US colleges was published already in 1983; university rankings as a tool of assessment was adopted in the United Kingdom (UK) in the 1990s (Harvey, 2005; see also Chapters 2 and 6 of this volume). There have also been rankings that cover certain language areas, such as the Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung (CHE) in Germany, which was launched in 1998, covering the German-speaking universities, also in Austria and Switzerland (see Chapter 12 of this volume). But worldwide attention to university rankings came with the Shanghai ranking, which first made a global comparison of HEIs in 2003.

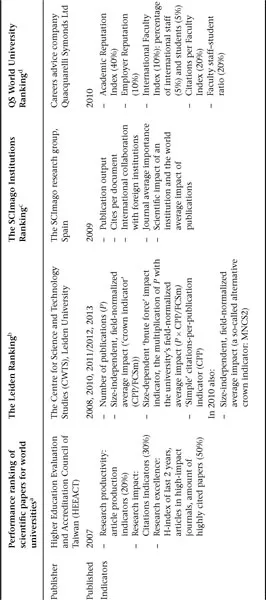

Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 present the global university rankings. Two major university rankings are published by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Institute of Higher Education and in the THES newspaper, and the Shanghai and THES rankings are perhaps the most prominent global university rankings at present. Having begun as an initiative of the Chinese government, the so-called Shanghai list has been ranking academic institutions annually since 2003. This ranking focuses on ‘measurable research performance’ (Liu and Cheng, 2005, p. 133). The first THES ‘World University Rankings’ was published in 2004 in response to a rising demand for advice on higher education (Jobbins, 2005, p. 137). The THES ranking concentrates heavily on research output and includes reputational evaluations of universities and assessments of the learning environment.

The rankings have been under criticism for their composition and normative underpinnings (Erkkilä and Kauppi, 2010). In Chapter 2 of this volume, Barbara Kehm discusses the problems of rankings in detail, including their possible negative effects. She concludes that the rankings are here to stay and we are compelled to live with them. Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 outline the background (producer, years of publication) and attributes of global university rankings. As the first global ranking, the Shanghai list has had a strong impact on the higher education (HE) field by identifying the key attributes of ‘excellence in higher education’. It relies heavily on bibliometrical analysis, individuals who have received academic awards and publication by the most prominent natural sciences journals.

Table 1.1 Global university rankings published in the first half of the 2000s

Table 1.2 Global university rankings published in the later half of the 2000s

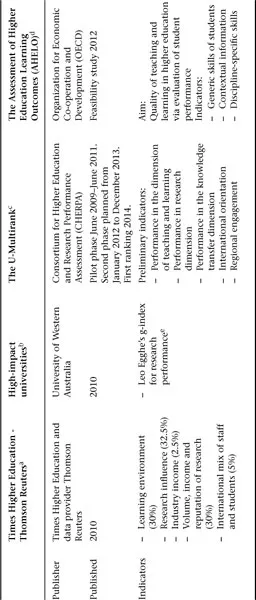

Table 1.3 Global university rankings published since 2010

The international recognition that the Shanghai ranking has attained was perhaps unintended, making it a standard by accident (Erkkilä and Kauppi, 2013). The Shanghai ranking is often cited as a domestic policy instrument for evaluating how Chinese universities fare against the ‘world class universities’. But as Bob Reinalda’s analysis (Chapter 3 of this volume) shows, despite the Shanghai ranking’s domestic use in China, the rankings are part of global and regional interactions that involve huge investments and markets in higher education and policy harmonization through approaches such as the Bologna process in Europe. In this respect as Reinalda argues, it was no mere accident that the first university ranking originated at an Asian HEI, coinciding with the significant investments in higher education in the region.

The development of global rankings in higher education can also be linked to the general drive for evidence-based policymaking and other global rankings. Since the 1990s, there has been a surge of various rankings of good governance and national competitiveness that have paved the way for other global policy assessments. The THES ranking and others that followed it can perhaps be more directly linked with this general development (Erkkilä and Kauppi, 2013). This was first produced by QS Consulting. QS compiled the THES ranking between 2004 and 2009, until it was replaced by Thompson and Reuters (first published in 2010). As Tables 1.1 and 1.3 show, there was also a change in the methodology of the ranking when the contracted producer changed. Though the THES ranking has perhaps concentrated more on the assessment of learning, it also uses the bibliometrical methods.

There are also lesser known global rankings of HEIs (Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3), including attempts at measuring the web presence of universities by the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities. There are also global rankings of HEIs produced in Taiwan (Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan, HEEACT), the Netherlands (Leiden University) and Australia (University of Western Australia) that tend to focus on the research output of universities. The Educational Policy Institute produces the only global ranking to assess national systems instead of HEIs, focusing on the affordability and accessibility of higher education. This provides an alternative view of the matter of higher education rankings, where the Nordic and Central European university systems are ranked higher than the Anglo-American and Asian ones.

The selection of rankings presented in Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 shows a developing field of expert knowledge in global higher education assessment that has become highly competitive, concerning actors as diverse as university research centers, newspapers and consultancies. There are also two recent additions to the field of ranking: U-Multirank by the European Commission funded Consortium for Higher Education and Research Performance Assessment (CHERPA) and the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). U-Multirank aims at providing a new type of mapping tool for comparing HEIs globally, based on the CHE ranking. AHELO assesses learning outcomes in higher education (Table 1.3).

U-Multirank is a new initiative launched by the European Commission to make a global mapping of excellence in higher education (see Chapters 2 and 3 of this volume). Here too, an earlier ranking stands in the background, as the development work of U-Multirank is largely based on the previous CHE ranking that initially covered HEIs in the German-speaking area, later including most Dutch universities (see Chapter 12 of this volume). The fact that EU is involved in producing a global university ranking is revealing in terms of the political implications of the rankings. The launch of U-Multirank was related to the felt need to have a ranking that would do justice to European universities (Erkkilä and Kauppi, 2010). This demonstrates the rankings’ ability to create policy problems in need of solution (cf. Bacchi, 1999). Moreover, the European Commission’s involvement in ranking of HEIs speaks of a European-wide policy ‘problem’ in search of a solution.

Global university rankings and the policy problem of European higher education

Though global university rankings do not assess national or regional HE systems as such but rather HE institutions, they nevertheless have geographical implications. How do German or French universities fare against British universities? And what about Europe vis-à-vis the US and Asia? The motivation for the Shanghai ranking was said to be that the Chinese authorities wanted to know how their HEIs fared in comparison to ‘world class universities’ (Kauppi and Erkkilä, 2011). Since the publication of the first global rankings, this concern has jumped onto the agenda of all countries that want to improve their HEIs’ standing in these gradings.

The future of higher education in Europe has been a policy problem for some time, leading to the outlining of a European university model. Here the historical perspective is often based on the Humboldtian tradition (Paletschek, 2011). Scholars treat this as a historical model that is now under threat through the Bologna process (Michelsen, 2010) and pursuing competitiveness in a knowledge-based economy (Nybom, 2003). However, there are also critical voices pointing to the invention of a Humboldtian tradition in the current debates on ‘Americanisation’, ‘privatisation’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘elite’, where the historical actuality of the Humboldtian model is seldom verified (Ash, 2008). Though the redefining of the European field of higher education cannot be reduced to university rankings, it is nevertheless becoming increasingly apparent that the rankings have the ability to shape the policy problems and the political and institutional responses to them (Hazelkorn, 2011; Kehm and Stensaker, 2009).

The global rankings are becoming cartographies of institutional traditions. From the European perspective, they have depicted a rather varied picture, with only a few top ratings in the league tables of ‘world class universities’. This has further strengthened the policy concerns over the state of higher education in Europe. Ironically though, the rankings now give an almost real time view of the HEIs and they lead to an invention of historical models, such as the European model of higher education (cf. Hobsbawn, 1987).

European HEIs are now increasingly being compared to the American and Asian universities. The rankings make such comparisons seemingly facile in portraying new pe...