eBook - ePub

Submerging Markets

The Impact of Increased Financial Regulations on the Future Growth Rates of BRICS Countries

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Submerging Markets

The Impact of Increased Financial Regulations on the Future Growth Rates of BRICS Countries

About this book

Submerging Markets is a valuable resource asset to the world academic community, government agencies, global business organizations and anyone interested in the impact of the new financial regulations and reforms implemented after the 2008 crisis, relative to the possible and probable future economic growth rates of the emerging markets (BRICS).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Submerging Markets by R. Marino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part III

The BRICS: Capital Flows Analyses

5

An Analysis of Brazil’s Economy Relative to Its Capital Flows

It’s not uncommon for a nation with a low savings rate to have a need for external sources of capital to finance domestic growth and Brazil is no different. The latest data shows that its savings rate is roughly 20 percent of GDP. In its peer group (BRICS), China’s saving rate is approximately 54 percent of GDP and India’s is around 35 percent of GDP. The data for Russia and South Africa compare more closely to Brazil.

In the case of China, I can make the argument that China understates its GDP by pegging the renminbi to the dollar, but when you take that into consideration China’s savings rate as a percentage of GDP would be closer to 27 percent. Outside of its peer group in the advanced economies, Brazil’s savings rate would compare favorably with the United States which is at 13.3 percent, Japan at 25.0 percent, and Germany at 25.7 percent. Obviously, the difference is that the advanced economies are established and the need for external sources of funds to finance domestic growth is almost nonexistent.

The ongoing stream of external funds to Brazil has not changed much in recent times. Brazilian growth skyrocketed from 3.2 percent in 2005 to 6 percent in June 2007 through June 2008. However, its current account changed from a 1.6 percent surplus to a 1.2 percent deficit in the same time period. This particular shift raises two issues of balance of payments undercurrents: yields on foreign capital invested in Brazil tend to be aligned with Brazil’s domestic growth agenda as opposed to the advanced economies monetary policy and the exchange rate is at the expense of foreign investors as opposed to the Brazilian borrowers.

Historically after the Latin American debt crisis of 1982, Brazil did not reenter the global financial arena until the 1990s and only after it restructured its entire debt obligations with its creditors. With the Real plan, hyperinflation came to an end in 1994 and that became the catalyst for a much stronger more, durable macroeconomic framework, which included the restructuring of privatization and sanctions were lifted against nonresident ownership of some of its core industries, for example oil, gas, and telecommunications. These changes culminated in a dramatic increase in foreign direct investments (FDIs) in the mid1990s. However, Brazilian yields were still attractive enough making Brazil’s debt instruments the more dominant foreign investment. There were periods of time from the mid1990s to around 2003 when foreign equity investments dominated, but for the most part, foreign capital inflows were earmarked for Brazilian debt instruments mainly in the form of public debt.1

Between 1999–2002 due in part to privatization inflows, FDIs averaged around US$25 billion roughly 4.3 percent of Brazilian GDP and in turn that number financed Brazil’s current account deficit. Foreign direct investments to Brazil went from around US$15 billion in 2005 to a staggering US$35 billion in 2007 with no privatization provisions. According to the UNCTAD (2008) World Investment Report, global FDI inflows experienced an overall increase of around 30 percent in 2007 totaling roughly US$1.8 trillion. Latin America and the Caribbean received approximately US$126 billion with US$35 billion going to Brazil, roughly 28 percent.2

Obviously, Brazil was the number one destination in the region followed by Mexico and Chile. By comparison and interestingly enough, South America extractive industries and natural resource based manufacturing saw an increase of 66 percent in the same time period amounting to over US$72 billion of capital inflows.3

In an earlier chapter, I mentioned that capital flows to the emerging market economies have basically resumed to the pre-crisis levels from the inordinate steep downturn following the world financial crisis of 2008 and estimates of future capital flows are on the high end. However since the resumption of capital flows from the decline following the global financial crisis, volatility has reared its ugly head and it’s become a very serious concern for emerging market economies. ‘But, especially since the financial crisis, which has highlighted the potential for pro-cyclical behavior of the financial sector, many EMEs are also concerned about the fragility that large inflows – and herd behavior that contributes to boom-bust cycles – can engender.’4

The ongoing stream of capital flows to Brazil and Latin America in general are subject to various and assorted economic market conditions. The inflows may reflect temporary interest rate differentials where yields are greater in Brazil as opposed to the home country, but this particular economic condition is subject to change, which could very well create at least a partial reversal capital flows. As of this writing, most capital inflows to Brazil originate in advanced economies who for the most part are struggling to regain the economic momentum of the pre-2008 global crisis. If the developed economies investment communities find that the pace to full recovery is too slow or even worse, if any experiences yet another recession, this dilemma could very easily trigger an aversion to risk and the investor may prefer to pull back to what is considered to be more of a safe haven.

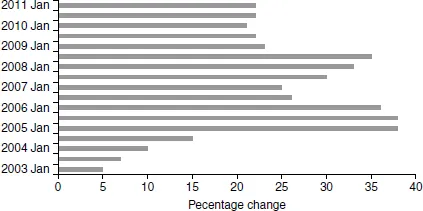

In recent times, Brazil has demonstrated an improvement in economic fundamentals. Consequently, a slow down or even ‘sudden stops’ in capital inflows should not be considered a ‘structural break’. More often than not, investors in the advanced economies want the best return on their investment and they’re willing to accept a level of risk if the risk/reward theory is underscored by a somewhat robust global economy, but if the majority of the developed economies are undergoing sluggish or even recessionary growth rates, the probable inclination of the average investor will be to pare down foreign investments knowing full well that in a global economy, it’s just a matter of time before Brazil’s economy will follow suit. The inherent problems associated with sudden changes in large capital inflows and large capital outflows are the overall complications found in macroeconomic policy management which can pressure exchange-rate appreciation along with possible monetary policy compromise. Moreover depending on the nature of the investment, a sudden surge or reversal of capital flows may ultimately affect Brazil’s domestic economic integration. The overriding aim behind capital flows is obviously growth (see Figure 5.1).

The BRICS growth rates have been robust, but the capital flows required to sustain robust growth rates have become even more volatile recently due in part to the sluggish nature of the advanced economies. Consequently at the end of May in 2011, a joint high level conference was held by the Brazilian government and the IMF in Rio de Janeiro to address these very issues. The focal point of the conference was titled ‘Managing Capital Flows in Emerging Markets’.5 In attendance on behalf of the Brazilian authorities, the IMF, and selected central banks were Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil, Alexandre Tombini Governor Banco Central do Brazil, Min Zhu Special Advisor to the Managing Director of the IMF, Paulo Nogueira Batista Executive Director of the IMF, Nocolas Eyzaguirre of the IMF, Jonathon D. Ostry of the IMF, Subir Vithal Gokarn Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India, Jose De Gregorio Governor Central Bank of Chile, Turalay Kenc Vice Governor Central Bank of Turkey, Jose Uribe Governor Banco de la Republica de Colombia, Atchana Waiquamdee Deputy Governor Bank of Thailand, Nelson Barbosa Filho Executive Secretary Ministry of Finance Brazil and Oliver Blanchard of the IMF.

Figure 5.1Credit to Brazilian households y/y percentage

Source: BBVA Research.

Brazil’s growth rates are pretty much on par with the rest of the BRICS. From 2006 through the forecasts of 2011 and 2012, Brazil’s growth ranged from a high of 6.1 percent in 2007 to a low of –0.6 percent in 2009, which puts Brazil in the middle of the pack with China on the top end in the same time period with a high of 13 percent in 2007 and a forecasted low of 8.7 percent in 2011. South Africa, on the other hand, came in at the low end of the group with a high of 5.6 percent in 2006 and a low of –1.7 percent in 2009.6

According to Min Zhu of the IMF, managing capital flows especially in Brazil and the rest of Latin America requires an adherence to solid economic principles. Policy interventions need to be in line and in place prior to sudden capital flow problems and these interventions need to advance solutions, which could alter or remove domestic distortions that for whatever reason exacerbate overall capital inflow problems. The scale of the proposed interventions should be balanced with the size and scope of possible capital inflow issues. Moreover, it’s the responsibility of each country to account for possible ‘spillovers’ and multinational effects of its activities.7

In terms of managing capital flows, established macroeconomic policies become the first line of defense: a free flowing exchange rate that is allowed to appreciate – but obviously not if the country’s currency is overvalued or if there’s a threat to the home country’s external currency stability – the creation of reserves aligned with the nation’s insurance metrics, a balanced approach to the country’s monetary and fiscal policies, which include tighter fiscal applications in an effort to prop up sustainable demand growth, and of course if times are right, lowering interest rates, which also helps maintain sustainable demand growth.

Furthermore, the above policy procedures have to be in place before the creation of capital controls or capital flow management measures. If not, any possible outcome concerning capital flows management will be distorted. Brazil’s ongoing efforts to streamline the volatility of capital flows speak well for its central bank and its central banker. The whole notion of precautionary measures in line with possible capital flow volatility makes for a more solid monetary and fiscal foundation: ‘reap the benefits of capital flows while safeguarding against the risks; stem the inflow pressures by reducing incentives for capital to cross the border and ensure they are avoiding external adjustment that may be necessary from a national or multilateral perspective’.

Brazil received roughly US$100 billion in portfolio and FDI capital flows in 2010 and an additional US$37 billion through the first quarter of 2011.8 In his presentation, Zhu makes the case that the IMF will evaluate the policies in place of the capital export countries. Furthermore in an effort to serve the national and global interests, he claims that the IMF has undertaken a very detailed, in-depth analysis of ‘outward spillovers’9 relative to capital flows. To that end, its evaluation will focus on the five largest economies in the world: the United States, the Euro area, Japan, China, and the United Kingdom. The results of their findings will be presented to the IMF Board in a series of Spillover Reports.10

In terms of the annual GDP percentage change of the five largest economies between 2006 and the 2012 forecast, the Euro Zone went from a high of 2.8 percent in 2007 to a low of –3.5 percent in 2010. Japan increased its GDP in 2006 by 3.0 percent which was the high in the aforementioned time period to a low of –4.1 percent in 2009. On the other hand, the United Kingdom increased its GDP by 2.4 percent in 2006 which was also its high between 2006 and the 2012 forecast, but the UK experienced a significant decline of GDP in 2009 of –5.2 percent and the United States followed a similar pattern hitting a high of 2.8 percent in 2006 only to watch its GDP decline by –4.9 percent in 2009.11 Interesting enough during the same timeframe, the BRICS averaged an increase on the high end of 8.56 percent and an average on the low end of 4.3 percent.12 The GDP trend line between 2006 and the 2012 forecast for the advanced economies is somewhat similar in size and scope, but its revelation is irrefutable. Obviously, an increase in GDP is much more difficult for a developed economy that is operating at full economic capacity as opposed to a more agile and flexible developing economy proving that the advanced economies are much slower to recover from a catastrophic economic shock, for example the 2008 crisis.

According to the IMF, capital controls are an appropriate tool for Brazil to manage capital flows contingent on the Brazilian government’s ability to monitor any ‘distortions’ resulting from the controls.13 Furthermore, Blanchard makes the case that Brazil’s economic outlook is ‘favorable’ with some signs of ‘overheating’. This evaluation came forth at the end of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- HalfTitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- PartI The Need for Increased Regulation

- Part II Capital Flows and Growth Rates Revisited

- Part III The BRICS: Capital Flows Analyses

- Conclusions

- Notes

- Index