![]()

PART I

Foundations of Food and Agriculture in the Caribbean

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Role of Agriculture in Caribbean Economies: A Historical and Contemporary Analysis

1.1 Overview

Agriculture has always been integral to the economies of the Caribbean. Potter et al. (2004) posit that the evolution of regional societies and economies in the Caribbean has been fundamentally determined by the plantation era and the inequalities and inequities created by slavery and colonialism. After emancipation in 1838, “new rural land use patterns and agrarian structures emerged reflecting a different, though still unjust social order” (Potter et al., 2004, p. 97). In the Caribbean of the post-emancipation period, there emerged a local peasantry made up of ex-slaves who left the sugar plantations and established independent communities, called free villages, with economies based on small-scale agriculture and other informal activities such as small-scale retailing, fishing, and charcoal burning. With export agriculture based on sugar still dominant, there developed an agricultural system characterized by a structural dualism (Barker, 1989, 1993). The features of this system are a large-scale export-oriented sector based on traditional plantation crops like sugarcane and banana juxtaposed with a small-scale farming sector focusing on domestic food crops that are staples in local diets and local cuisine (Barker, 1993; Beckford and Bailey, 2009). This duality has persisted and characterizes agriculture in many Caribbean countries to this day.

Agriculture in the Caribbean is characterized by significant diversity, with each island having its unique landscape shaped by economic imperatives, cultural history, and environmental realities (Potter et al., 2004). Agriculture benefits Caribbean economies in a number of ways. These include contribution to gross domestic product (GDP), export earnings, employment, and domestic food supply. It provides industrial raw materials, is the basis of rural livelihoods, and is still a major land-use activity in many of the countries in the region (Deep Ford and Rawlins, 2007; Potter et al., 2004).

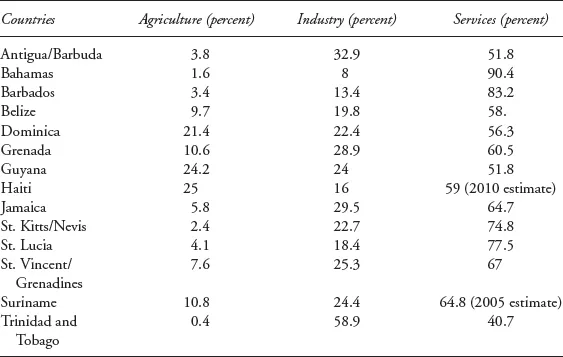

Agriculture is still very important to the Caribbean but its economic significance is changing as economic imperatives shift and island economies diversify to become more industrial based and service and technology oriented. In terms of agriculture’s contribution to GDP, there is a declining regional trend (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Comparative contribution to GDP in the CARICOM

Source: CIA—The World Factbook 2012 (2011 estimates unless otherwise noted).

Regionally, agriculture makes up around 25 percent of GDP, making the highest contributions to the economies of Haiti and Guyana. This compares to around 5 percent in developing countries and above 40 percent in Africa and Asia. In St. Kitts and Nevis, agriculture’s contribution to GDP fell from 40 percent in 1964 to less than 6 percent in 2000. In Barbados, it declined from 38 percent in 1958 to 4 percent in 2000 (Potter et al., 2004). Unlike the developed world, where agriculture’s declining contribution to GDP coincided with a rapid growth in urban industrialization, in the Caribbean the decline is matched by a rapid expansion of the service sector, which is dominated by tourism. Regionally tourism now contributes up to 75 percent of GDP, with notable exceptions being Guyana and Haiti, where its contribution is less than 50 percent (Potter et al., 2004). Ironically the growth of tourism has not led to a corresponding growth in agriculture, as was expected (Lewis, 1958; Momsen, 1972; Timms, 2006; Rhiney, 2009). Today agriculture in the region is in decline, with significant implications for food security. Traditional exports like sugar and bananas have not been able to withstand the loss of preferential access to markets in Europe. Sugar in particular has declined dramatically in terms of its importance to foreign exchange earnings, although it still employs a significant portion of the labor force in former slave economies in the region. For example, in St. Kitts and Nevis, sugar accounted for 78 percent of export earnings in 1978, but in 2004 it accounted for just 2 percent of export earnings though it employed 8 percent of the labor force and occupied 30 percent of arable lands (Potter et al., 2004). Domestic food production has declined sharply over the past 15 years in particular, and today the Caribbean is a net importer of food—“a paradise that cannot feed itself” (Ahmed and Afroz, 1996, p. 4). Only Guyana and Belize are net food exporters (Deep Ford and Rawlins, 2007; Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute, 2007). There is no real consensus as to when the decline in agriculture may have started in the Caribbean, but Ahmed and Afroz (1996) postulate that the turning point for Jamaica may have been after independence in 1962 and that the decline would have intensified during the 1980s under structural adjustment policies. In 1981, according to Ahmed and Afroz, there was a 40 percent increase in food imports due to the government’s decision to remove existing import restrictions on a range of foodstuffs that could be produced locally. This resulted in competition from cheaper imports, which in turn led to a 12 percent reduction in domestic agricultural production the following year. Weis (2004) described this decline of domestic food production in Jamaica as a crisis. This is supported by Ahmed and Afroz (1996, p. 7), who submitted that “[n]ot only has Jamaica been unable to expand its agricultural items, but it faces a major food crisis because of declining production of staple food for the local market.” In addition, agriculture as a percentage share of GDP and total labor force has also declined in recent times. According to a study done by the World Bank (1993), agriculture’s percentage of GDP in Jamaica decreased from 8.3 percent to 5.7 percent between the 1970s and 1985. At the same time, the percentage of the labor force employed in agriculture dropped from 30 to 24 percent.

This chapter explores the role and place of agriculture in Caribbean economies in the context of continuity and change and the implications for regional food security.

1.2 Contextualizing Agriculture in the Caribbean

Fifty years after the English-speaking Caribbean started to rid itself of colonial rule with the independence of Jamaica, and 174 years after emancipation, agriculture in the Caribbean is still fundamentally shaped by the legacy of the plantation system and the colonial political economy in which it originated and flourished (Potter et al., 2004; Timms, 2008). This political economy connected Caribbean economy and society to extraregional markets in the metropolitan countries of Europe, a link that has persisted in the contemporary Caribbean. Plantation crops such as sugarcane throughout the region and other crops like nutmeg, arrowroot, and pimento in, respectively, Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Jamaica were exported, while inputs to agriculture, most of the foods eaten by the masses such as flour and salted fish, and consumer goods were imported. In the plantation system and throughout the colonial era, sugar was king and plantations cultivating sugarcane and other export crops were established on the best arable lands. In the case of sugarcane, these were coastal plains and interior lowlands and alluvial plains. This left only marginal lands for small-scale domestic agriculture. During slavery, the provision grounds made available to slaves to grow some food for themselves were established on the most marginal plantation land that was basically unsuitable for sugarcane cultivation. In 1838, slaves were emancipated throughout the British Empire. Former slaves could continue to work on the plantation for wages; however, desperate to distance themselves from their former lives, many of them chose to leave the sugar estates and established independent communities. Farming and other informal activities became the basis of rural livelihood in these free villages. With all the best lands occupied by sugar plantations, marginal land on hilly terrain and steep slopes was utilized by small-scale farmers. Small-scale domestic agriculture in the Caribbean came to be associated with hillsides and is sometimes described as hillside farming. As part of the dichotomized and dual structure of Caribbean agriculture, sugarcane still occupies the best lands. Sugarcane cultivation was in decline throughout the region even before preferential markets in Europe were dismantled, after which it became even more unprofitable and uncompetitive; sugar is no longer king. In many islands, land that has been taken out of sugarcane cultivation has not been made available to smallholder farmers. In Jamaica, some former sugarcane lands have been put into banana cultivation—another export crop, but which also has a huge domestic market given its critical role as a staple food. Elsewhere, like St. Kitts and Nevis, former sugar plantations have been used for housing developments.

Agriculture in the Caribbean did not originate with European colonization. The first peoples in the region are thought to have been Amerindians, mainly Tainos, Arawaks, and Caribs. They were all agriculturalists to varying degrees and their influences can still be seen in contemporary Caribbean agriculture. Crops like beans, corn, cassava, and pumpkin, which were grown by the first peoples, are still grown around the region today. Other cultural influences can also be identified, including African, East Indian, and European. African influences are found in many of roots and tubers grown across the region. In Guyana and Trinidad, which both have large populations of people of East Indian ancestry, rice is a popular crop. Vegetables such as carrots, onions, and cabbage were introduced from Europe, and breadfruit, also popular throughout the region, was introduced from the Pacific Islands.

1.3 The Role of Agriculture in a Global Context

According to Meijerink and Roza (2007), there appears to be somewhat of a paradox in the role of agriculture in economic development. This is manifested in the fact that while agriculture’s contribution to GDP has been steadily declining, the production of some critical crops like cereals has been increasing. It would seem that agriculture’s role in the total economy might actually decline as it becomes more successful (Meijerink and Roza, 2007). They suggest that it might be tempting to say that an emphasis on other sectors of the economy at the expense of agriculture facilitates economic growth. But Haggblade (2005) posits that the agricultural sector is still important in economic development, but that the overall economic growth reduces the role of agriculture when measured in terms of contribution to GDP. This analysis makes it clear that assessing the role and contribution of agriculture in isolation from the state of other economic sectors constitutes an incomplete approach. The majority of the world’s poor live in rural areas and for these people agriculture is the main source of employment and income. It was estimated that in developing countries, 53 percent of the total work-force was employed in agriculture, with the figure in sub-Saharan Africa being 60 percent (World Development Indicators, 2006).

1.4 The Role of Agriculture in the Caribbean

Agriculture makes several important contributions to Caribbean economies. First, it still contributes significantly to GDP in most countries of the region. In the very small islands its role is not as important. For example, in the Bahamas only approximately 2 percent of the total land area is cultivated, and farming is more accurately defined as gardening and serves mostly subsistence functions. Still, agriculture accounts for 3 percent of GDP. Increased investments in other sectors and continued bias against agriculture, especially the small-scale farming sector, have resulted in increased contributions of other sectors to GDP and a decline in agriculture’s contribution. In Antigua/Barbuda, for example, agriculture accounted for 20 percent of GDP in 1961, but with the collapse of the sugar industry and the development of a thriving tourism industry, this declined, and in 2000 agriculture contributed only 4 percent to GDP (Potter et al., 2004). In other countries, export agriculture is an important economic activity and contributes significantly to foreign exchange earnings. This applies to traditional export crops like nutmeg in Grenada, arrowroot in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, rice in Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago, bananas in the Eastern Caribbean and Jamaica, sugar in many islands, and coffee in Jamaica. In some islands like Jamaica, there is a growing category of relatively recent agricultural export crops, mainly roots, tubers, and winter vegetables developed since independence. These have contributed significant foreign exchange earnings in the last two decades and have the potential to be even more important. Agriculture also plays a critical role in food security throughout the region, providing domestic supply of food and energy for the workforce. In this respect it serves to save foreign exchange that would otherwise be spent on food imports.

In most Caribbean countries agriculture is the major economic land-use activity, although it is contributing less and less to GDP. Official data typically indicate single-digit contributions of agriculture to GDP. For example, it is estimated that agriculture contributes 8 percent to Jamaica’s GDP, but the Inter-American Institute for Co-operation in Agriculture (IICA) suggests that when backward and forward linkages in the commodity supply chain are accounted for, the contribution of agriculture to GDP is three to seven times higher than that reported in national statistics. IICA studies in Latin America have shown that agriculture’s contribution to GDP is usually underestimated. For example, in Argentina, official statistics indicate a 4.6 percent contribution of agriculture to GDP, but this figure increases to 32 percent when forward and backward linkages are considered. In Brazil, the official figure of 4.3 percent rose to 26.2 percent; in Chile, Mexico, and Costa Rica, respectively, official figures of 5 percent, 4.3 percent, and 11.3 percent increased to 32.1 percent, 24.5 percent, and 32.5 percent (IICA, n.d.).

The importance of agriculture is underestimated because of how its contribution is perceived and measured. In the Caribbean and the developing world in general, agriculture’s contribution to GDP tends to be measured only in terms of primary production. The value-added elements of agro-processing and the employment function and other linkages are rarely taken into account. It should be noted that the same is true of developed countries. For example, in the United States, the official estimate of agriculture’s contribution to GDP is 0.7 percent, but when backward and forward linkages are considered, this increases to more than 8 percent (Meassick, 2004).

The contribution of agriculture therefore tends to be underestimated. For one thing, its importance in agrobusiness is not always accounted for (Meassick, 2004). Also, agricultural professionals and workers are not counted when the role of agriculture is being assessed. Farmers are not the only category of agriculturalists (Meassick, 2004). There are also agro-processors, food inspectors, extension workers, educators, veterinarians, engineers, and salespeople and marketers. The agricultural sector should be assessed in its broadest sense and not narrowly defined in terms of primary production. According to the IICA, agriculture has a threefold role in national development in the Caribbean: food security, social stability, and environmental protection. It is critical to rural development and prosperity as it absorbs surplus labor and provides income and livelihood. Livelihood assets in the rural context are often defined largely in agricultural terms (Campbell, 2011).

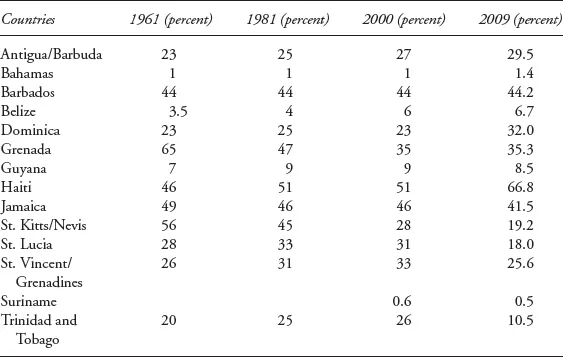

According to Potter et al. (2004), employment in agriculture as a percentage of the total labor force has declined in recent years. Among CARICOM countries, the agricultural labor force ranged from 8 percent in Trinidad and Tobago to 20–30 percent in Belize, Dominica, Grenada, and Jamaica (Potter et al., 2004). In terms of land use, agriculture still occupies significant space: about 45 percent in Jamaica and Barbados, and 30 percent in the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) countries. On the other end of the spectrum, only 2 percent of land in the Bahamas is cultivated, largely because of terrain and soil constraints. Like the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands and Montserrat have very small percentages of land under agricultural cultivation. In some countries, such as Guyana and Belize, agricultural land use has increased, while in others, such as Grenada and St. Kitts and Nevis, it has declined (see table 1.2). In the former, expansion in rice cultivation led to the increase. In Belize, where less than 7 percent of land is under agriculture, there has been a significant increase in agricultural land in the last 25 years and a doubling since 1961 (Potter et al., 2004).

It was estimated that in 2009 agriculture accounted for 7 percent of GDP in Jamaica but absorbed a significant 21 percent of the employed labor force (CARICOM Secretariat, 2009). It contributed greatly in provision of fresh produce for agroprocessing and also accounted for more than 20 percent of exports in 2004 (CARICOM Secretariat, 2009). Despite the obviously important role of agriculture in the economy, the country still imports 80 percent of the cereal and cereal products used, as well as 12 percent of its meats and a growing volume of fruits and vegetables. Agriculture can play an even greater role through the expansion of aggregate output and value added.

The role of agriculture in the Caribbean has been shaped to a large extent by the declining fortunes of traditional export crops, especially sugar and bananas. Both have suffered as a result of the loss of preferential access to international markets in Europe. In the Eastern Caribbean, the banana industry has likewise been adversely impacted by loss of preferential markets and competition from cheap banana produced in Central America (Grossman, 1998). Today domestic food crops outperform export crops and represent the driving force behind Caribbean agriculture. In Jamaica, for example, yam cultivation is one of the few bright spots in the agricultural sector (Barker and Beckford, 2006) and makes an important contribution to export earnings.

Table 1.2 Changes in agricultural land in CARICOM, 1961–2009

Source: Adapted from Potter et al. (2004) and World Bank (2010) (data.worldbank.org>indicators).

Agriculture in the Caribbean is also negatively impacted by the ubiquitous natural disasters to which the region is susceptible (McGregor, Barker, and Campbell, 2009; Campbell, 2011; Beckford, 2009). The main ones are meteorological hazards such as hurricanes, droughts, floods, and landslides. Hurricanes get most of the headlines and have the most immediate impact, but the scenario is really one of alternating cycles of hurricanes, drought, and floods, often experienced in the same year. The impact of natural disasters is discussed in chapters 11 and 12 in this volume, but billions of dollars in losses have been incurred by the agricultural sector over the last few decades (McGregor et al., 2009; Campbell, 2011). The last two decades have seen an increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, and the agricultural sector throughout the region has taken a pounding. The time to recover from extreme events is getting shorter and shorter, and this affects stability and consi...