- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through rich stories of African migrant women in Johannesburg, this book explores the experience of living between geographies. Author Caroline Kihato draws on fieldwork and analysis to examine the everyday lives of those inhabiting a fluid location between multiple worlds, suspended between their original home and an imagined future elsewhere.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Migrant Women of Johannesburg by C. Kihato in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Emigration & Immigration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Welcome to Hillbrow, You Will Find Your People Here

“Get out! GET OUT!”

Tired, hungry and disorientated, Fazila squinted in the bright light streaming through the truck’s back door. The driver cut a large figure, and his silhouette offered her some respite from the glaring afternoon sun. As her eyes adjusted to the light, she asked “Are we there?” barely recognizing her own voice. She had not spoken for days in her full voice and her mouth was dry. Had she left Lubumbashi for South Africa four, five days ago? She could not be certain and had lost count. Her journey to South Africa seemed like one long arduous night cramped at the back of the truck with no windows.

Fazila’s journey had, in fact, started not four or five days before, but a few months before, in 2000 in a Kinshasa jail. She had been taken in for questioning by the Kabila regime because of her links to a man who had worked for the deposed president, Mobutu. After a few days in jail, she bought her way out and flew to Lubumbashi where she found a driver who, for a fee, would smuggle her into South Africa. Without a passport or a change of clothes she climbed aboard the truck with all the money she had, and left for Johannesburg. “I abandoned everything. I am going to a country where I don’t know what is going on there. I left my studies, family, my life. I lost everything,” she had said to me in the livingroom of her Berea apartment. From Lubumbashi, the truck entered Zambia. Fazila and seven others, including a woman with a two-year-old child, travelled through Zambia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in silence. The border guards and the police at roadblocks could not know that the driver was carrying human cargo. They were crossing the borders illegally. Under the cover of darkness, they made pit stops once a day to go to the toilet in bushes.

“What day is it?” she heard someone in the truck ask the driver.

“Same day it is where you came from. Welcome to Hillbrow, you will find your people here.”

Fazila gathered herself and stepped tentatively into the commotion on the streets. She blinked as her eyes adjusted to the light. As she straightened the creases on her clothes, a heady feeling of excitement and fear came over her. “I am here, I am in Johannesburg,” she thought to herself. For a few moments, she forgot her anxieties and listened to the banter of street life—cars honking, a police siren, and people buying and selling. After the hushed silence and the irregular rhythm of the truck’s overextended engine, the cacophony of the city’s sounds accosted her ears. She stood on the sidewalk and looked up at the towering apartment blocks. Down the street, she noticed traffic lights, each set turning green and then, moments later, red, as if in a synchronized dance. The smell of fried chicken mingled incongruously with the exhaust fumes from a nearby taxi. How far she had come from the place of her birth, Bukavu! As reality began to creep in, her fear returned. She needed to focus on survival, finding food, accommodation, and work, in that order. Looking around her new host city, she caught a glimpse of a cylindrical skyscraper, the iconic and infamous Ponte City. She did not know then, but at 54 stories high it is the tallest residential building in Africa. With a history of suicides, gangs, international drug cartels, and stories of revival, Ponte, Norman Ohler writes, “is Johannesburg’s infamous landmark.”1 She remembers noticing its rooftop, a gigantic blue and white billboard advertising VODACOM.

Johannesburg: A City Between and Betwixt

For those living in Johannesburg’s wealthy northern suburbs, its inner city is perplexing, impenetrable, and dangerous. Stories of crime, drugs, the concentration of “illegal aliens,” and poverty lament the decay of what was once the symbol of South Africa’s gold wealth and prosperity. But these stories of despair are only a partial rendering of Johannesburg’s infamous center. In truth, Johannesburg’s inner city is an ambivalent place—a site of both opportunity and lack, hope and despair.

In many ways, this has been Johannesburg’s story since its founding as a mining camp in the mid-nineteenth century. After the discovery of gold in 1886, the city became a magnet for people seeking their fortune in its mines, industries, and growing service sector. By the 1900s, Johannesburg had a class of black contract laborers living in single-sex dormitories or overcrowded slums, who needed permission to be in the city.2 They became the city’s workhorses who never belonged. Wealth and success is almost always accompanied by poverty and misfortune. And Mongane Wole Serote’s poem “City Johannesburg” captures this paradox in the story of a migrant worker who leaves the warmth of “his love, comic houses and people” in search of the city’s wealth in an unforgiving, alienating, and racially segregated environment. At the height of apartheid and its industrial glory, Serote’s Johannesburg is at once the source of life and of death to those who ventured to work in its mines and industries.

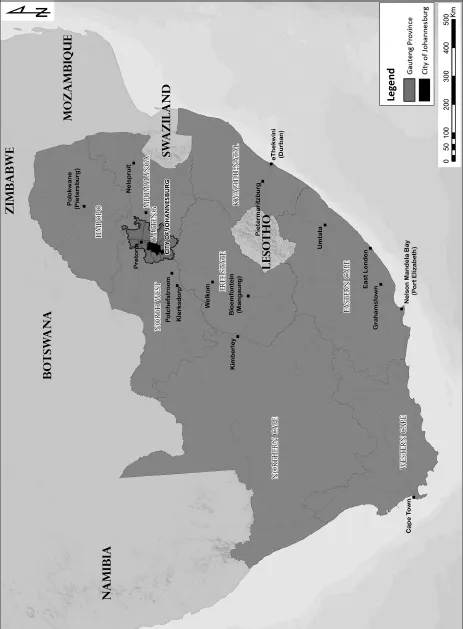

Map 1.1 Locating Johannesburg within Gauteng and South Africa

Johannesburg is located in Gauteng province. Most of the country’s internal and international migrants find their way to Gauteng because of its dominant economic position in South and Southern Africa. With a population growth rate of 2.7 percent between 2001 and 2011, Gauteng is the fastest growing of South Africa’s nine provinces.3 It is also the country’s most populous province, with 12.3 million people, representing 23.7 percent of South Africa’s population.4 It is estimated that about 3.75 million people live in the city of Johannesburg.5

The history of Johannesburg’s inner city and its surrounding areas has been covered elsewhere6 and is not the focus of this book. But its beginnings as a mining town, and the subsequent racialized nature of its industrialization, had an impact on how migrant labor and, in particular, black populations saw themselves in the city. The apartheid city produced a group of people who lived and depended on it, but could not claim it as their home. Blacks were temporary sojourners to the city of gold. And although they toiled in its mines, industries, and streets, they had no rights to live in it or make decisions about its future.7 Those allowed temporary domicile could not live with their families because of restrictions on movement.8 These were people useful only for the duration of their economically active years. Like the protagonist in Serote’s poem, their lives straddled Johannesburg and their homes in South Africa’s rural areas and neighboring countries. Today’s cross-border migrants may not face apartheid’s harsh racial policies, but, like the migrants of yesteryear, they continue to live between their countries of origin and the city of gold—never fully at ease in their adopted city.

Figure 1.1 Johannesburg’s dazzle—big brands and city lights in the Central Business District

The Setting

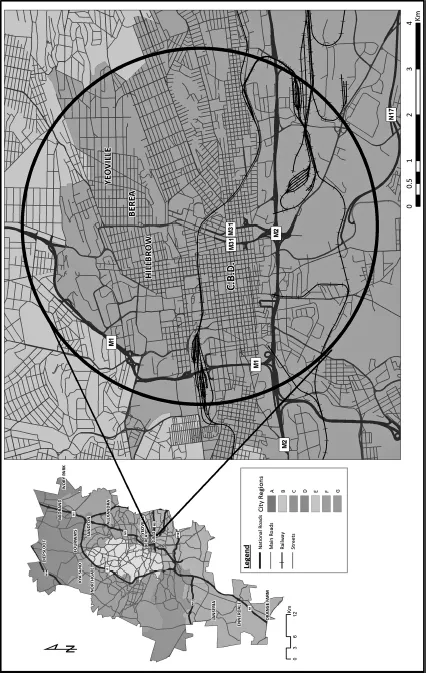

This book is set in Johannesburg’s inner city—the Central Business District (CBD) and areas northeast of it where the residential suburbs of Berea, Hillbrow, and Yeoville lie. Unlike most of Johannesburg, the inner city has a high-density residential stock that was built in the 1930s during an economic upturn.9 The apartments, particularly in Hillbrow and Berea, were built to house the city’s well-to-do, providing shops and services to match a sophisticated urban lifestyle. It is the availability of accommodation, the retail opportunities that high-density living provides and the inner city’s central location that continues to attract new migrants today. But, like cities elsewhere, Johannesburg’s center has seen periods of booms and busts. At the culmination of the CBD’s decline in the early 1990s was the flight of big capital. The exodus of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, De Beers, and Gold Fields, and the closure of the iconic Carlton Hotel sealed the city’s fate. Although today there are signs of the city’s revival with the development of new art, knowledge, and lifestyle precincts like Arts on Main, these investments remain small, niche, and exclusive, appealing to artsy, green, and urbane lifestyles.10 In their midst however, remains a sea of decaying, overcrowded, poorly managed buildings and infrastructure.

As the CBD was experiencing capital flight, the adjacent residential areas of Yeoville, Berea, and Hillbrow were also undergoing their own demographic and economic changes. The early 1990s saw an influx of people from South Africa’s rural areas and other African countries into the inner city, which urban authorities were ill-prepared for. The timing seemed right for Africans from both within and outside of South Africa. The dreaded pass laws that restricted blacks’ residence in the city had been repealed, allowing them to become bona fide residents in the city. For international migrants, the lifting of travel sanctions after the release of the African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela made it legal for foreign Africans, whose countries had participated in the boycott against apartheid, to travel to South Africa. Moreover, the devastating impact of Structural Adjustment Programs on African economies and livelihoods;11 and the growing political and civil unrest in parts of the continent propelled people to travel to places that were safer and had economic opportunities. South Africa became such an option for international migrants.

Map 1.2 Map of Johannesburg and the study area

The number of foreign-born migrants in Johannesburg remains an intense point of debate. City officials tend to exaggerate the numbers, some believing that up to 86 percent of Johannesburg’s population comprises of illegal foreigners.12 Far from these estimates, the 2011 census puts the number of foreign-born nationals in country at 3.2 percent.13 Although the number of foreigners in Johannesburg is likely to be above the national average, it is unlikely that eight out of every ten people in the province is foreign born. Measured estimates seem to suggest that between 13 and 14 percent of the city’s population are foreign-born.14 Whatever the numbers, the inner city provides many newcomers from South Africa and beyond a foothold into the city. Population figures in 2010 show that the CBD, the area where this research took place, has the highest population densities in Gauteng—with 64, 623 people per kilometer.15 A combination of factors—pressure on infrastructure, the lack of investor confidence, poor building maintenance, absentee landlords, and overcrowding—have resulted in the physical decay of many residential blocks and the infrastructure that serves them. The presence of international drug syndicates and gangs16 has sealed inner city Joburg’s reputation as an area riddled with “crime and grime.”

Figure 1.2 The city as we live it, cooking in the corner of a studio apartment in Hillbrow

It is the transitional aspects that drew me to inner city Johannesburg to study women from other parts of Africa. Hanging out with them, I became aware of the fluid nature of Yeoville, Berea, and Hillbrow. These parts of the city seemed to be places that migrants passed through rather than settled in. A place where newcomers saw themselves living for only a short duration of time—their sights set on Johannesburg’s northern suburbs or on cities in North America or Europe. In 1999, Morris found that many cross border migrants “saw South Africa and Hillbrow as a temporary stop.”17 A few years later, in 2006, a survey conducted by the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), Tufts University, and the French Institute of South Africa (IFAS), came to similar conclusions, confirming broader trends in what I witnessed in my fieldwork. The survey showed that the majority of respondents in the study, both local and foreign, imagined their lives elsewhere in the city, or outside the country.18 Both South Africans and foreign-born migrants keep strong ties with kin and communities elsewhere, even as their everyday lives are physically rooted in the city. Few who live in the inner city stay there longer than three years, perceiving it as inappropriate for raising a family or living with a spouse.19 Those who do stay on live as if suspended in society, aspiring for lives elsewhere. It is within these broad population dynamics that foreign-born migrant women’s experiences of the inner city are located....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: Welcome to Hillbrow, You Will Find Your People Here

- 2 The Notice: Rethinking Urban Governance in the Age of Mobility

- 3 Between Pharaoh’s Army and the Red Sea: Social Mobility and Social Death in the Context of Women’s Migration

- 4 Turning the Home Inside-Out—Private Space and Everyday Politics

- 5 The Station, Camp, and Refugee: Xenophobic Violence and the City

- 6 Conclusion: Ways of Seeing—Migrant Women in the Liminal City

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index