eBook - ePub

Renewable Energy Transformation or Fossil Fuel Backlash

Vested Interests in the Political Economy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Renewable Energy Transformation or Fossil Fuel Backlash

Vested Interests in the Political Economy

About this book

Renewable energy is rising within an energy system dominated by powerful vested energy interests in fossil fuels, nuclear and electric utilities. Analyzing renewables in six very different countries, the author argues that it is the extent to which states have controlled these vested interests that determines the success or failure of renewables.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Renewable Energy Transformation or Fossil Fuel Backlash by Espen Moe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Energy Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that China will no longer sacrifice the environment for temporary economic growth (CCICED, 2013); a year later Premier Li Keqiang followed up by stating that China ‘will resolutely declare war against pollution as we declared war against poverty’ (Guardian, 2014a; GWEC, 2014, p.14). Whether China lives up to its promises obviously remains to be seen, but clearly environmental and energy issues now attract serious attention from very powerful political and industrial actors. In a world where oil prices, despite their recent dramatic fall, had long been stable at more than US$ 100 per barrel, where peak oil (as in the point of maximum oil production (after which it will inevitably decline)) is fast approaching, and where climate change is becoming an evermore concrete and tangible challenge, a fresh look at energy policy, and renewable energy policy in particular, is very much in order.

Chinese authorities are not alone in taking these issues seriously. (Rather, their statements reveal a somewhat belated emphasis of their importance.) Since the 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown at Fukushima, both Japan and Germany have gone a long way toward ending their dependence on nuclear power. In the US, every president since Richard Nixon has concerned himself with energy security. President George W. Bush in 2006 warned that ‘America is addicted to oil.’ In 2010 President Barack Obama urged the US to make serious investments in clean energy rather than just surrendering the clean jobs of the future to Germany and China, and in 2014 he used the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to bypass a gridlocked Congress and impose stricter regulations on the power sector (in particular, the coal industry) (EPA, 2014b; New York Times, 2006; White House, 2010). In Denmark, the parliament has decided that by 2050 the Danish energy system will be fossil free (Lund et al., 2013). And in Norway, former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg in his 2007 New Year’s speech somewhat pompously labeled the development of Carbon Capture Storage (CCS) technology as Norway’s equivalent of the moon landing, and its contribution to solving the world’s energy and climate problems (VG, 2007).

Some of these initiatives and utterances may prove to have been little more than rhetoric and lofty plans. After all, worldwide emissions have never been higher than in 2013.1 But even lofty plans and rhetoric often provides a suggestion as to which way the wind blows, and about what stirs the public imagination. It is certainly clear that energy issues are at the forefront of the political discourse like never before. Energy security no longer just means more oil on bigger oil tankers. It means that we, to an ever greater extent, need to come up with new ways of producing energy (as well as new ways to reduce energy consumption). And preferably, the new energy alternatives need to be far less polluting than the old ones. If not, the Chinese war on pollution would be lost before it had even gotten underway, and the Danish plan to become fossil free would be nothing but fine words on glossy paper. While there is no single solution to these problems, it is very hard not to see renewable energy as one of them.

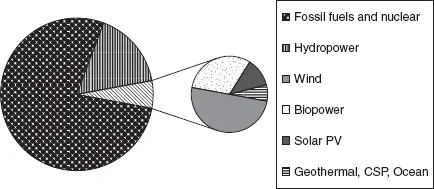

So, renewable energy must be pretty important, then? The question may seem puzzling. But the first and most obvious answer is that, in and of itself, it really is not. Out of global final energy consumption, renewable energy (not including hydro) accounts for no more than 1.2 percent (2.0 if biofuels are included), and out of all global electricity production, the wind and solar share is 3.6 percent, with 2.9 percent for wind and 0.7 for solar (see Figure 1.1).2 These numbers increase year by year, but they are still very small, and fossil fuels provide a fairly steady 80 percent of our energy (REN21, 2014). So, why spend an entire book on something that accounts for only a little more than 1 percent of global energy consumption?

Figure 1.1 Renewable share of electricity production, 2013

Source: REN21 (2014).

The more roundabout answer is that the world is currently facing, or in the midst of, a number of different crises. Some are immediate, some are drawn-out, and others are mainly about the future. But since 2008 we are in the midst of a financial crisis. It is the biggest economic crisis the world has faced since 1929, and it has been particularly protracted in Europe. In China, stimulating renewable energy industries – industries perceived as major growth industries of the future – was part of the Chinese government’s plan for China to keep growing through the crisis, and notions of renewable industry heading a wave of green economic growth was much heard both in Europe and in the US. Second, we may be looking at an energy crisis. By all means, this is a different kind of crisis than the financial crisis and we are slowly adjusting to a world where oil is far costlier than a mere decade ago, but when the oil price started climbing, the increase was extremely abrupt, from less than $20/barrel in 2002 to $50 in 2007, before peaking at $147/barrel in 2008. It has fluctuated considerably since then, but since 2011 only rarely dipped below $100/barrel. Granted, at the time of writing, and in less than a year, the oil price has more or less halved, currently standing at around $60/barrel, analysts warning that the dip may be more than just temporary. Still, the long-term forecasts are for prices to once again increase. The International Energy Agency (IEA) (2013c) predicts $128/barrel by 2035, and before the oil price started crashing, an IMF working paper suggested as much as $180/barrel already by 2020 (Ayres, 2014). This estimate is now unlikely to be fulfilled, but it does suggest that eventually prices will inexorably start rising again.

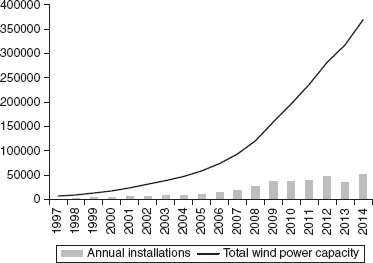

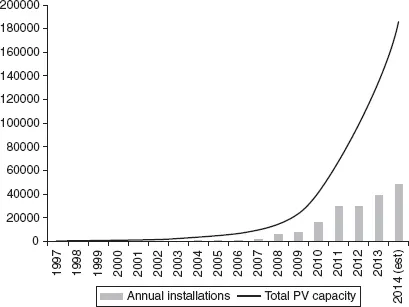

The oil price contributes to the financial crisis in the sense that energy prices this high are undoubtedly bad for the overall economy. However, the real energy crisis is more of a drawn-out thing. Peak oil has been a concern for decades, and while it represents no immediate problem (we keep pushing it into the future), it is quite obvious that today’s fossil fuel regime cannot last forever, for the simple reason that the resources will eventually exhaust (or at least dwindle to such an extent that they become exorbitantly expensive). Third, we may be looking at a climate crisis, which is another drawn-out, long-lasting crisis where the immediate impact is not particularly severe, but the long-run consequences are far-reaching. Thus, if peak oil is upon us, not only do we need to compensate dwindling reserves of fossil fuel with something else, but in order to combat global warming, this ‘something’ else needs to be fairly emissions-free. Thus, while renewable energy is not the answer to all our worries, first it could provide us with new growth industries, second with more energy, and third with relatively emissions-free energy. It could go some way to providing solutions to all three crises (obviously renewable energy technologies still have to become cheaper and more efficient). And if we look at how fast renewable energy has expanded, the prospects may not even be completely far-fetched. Since 2000, on average, wind power installations have increased by 24 percent annually, whereas PV (photovoltaic) capacity has increased by an average of 41 percent. In 2000, global wind power capacity was not even 20GW, whereas in 2014 it reached 370GW (see Figure 1.2). For solar, in 2014, capacity reached an estimated 185GW, up from a mere 1.5GW in 2000 (see Figure 1.3) (EPIA, 2014a; GWEC, 2015; REN21, 2014; SolarServer, 2015; WWEA, 2014).

But if all this is true, and if renewable energy can potentially be this important, why do we not just install it? Sheikh Zaki Yamani, Saudi Arabia’s powerful minister of oil and mineral resources from 1962 to 1986, once famously said ‘the Stone Age did not end for lack of stone, and the Oil Age will end long before the world runs out of oil’ (quoted in Aleklett, 2012, p.121). In his mind, oil would be replaced by more efficient forms of energy as new and better technologies were invented, and this would occur long before the oil had been extracted. Thus, if renewable technologies were already competitive, the market mechanism by itself would guarantee that renewable energy is fed into the system in such quantities that it makes for an energy transition. One of the goals of this book is, however, to show why this is not so, and how in most countries the institutional setup often contains a heavy bias in the direction of fossil fuels. Thus, there is no guarantee that Sheikh Yamani is right in suggesting that this problem will take care of itself. Michael Klare’s (2012b) prediction that we are instead facing a race for the planet’s remaining fossil fuel resources seems equally prescient. The Oil Age may easily end exactly because we run out of oil.

Figure 1.2 Total and annual installed wind power capacity, 1997–2014 (MW)

Sources: GWEC (2015); REN21 (2014).

Figure 1.3 Total and annual installed solar PV capacity, 1997–2014 (MW)

Sources: REN21 (2014); SolarServer (2015).

In a world without learning effects, economies of scale, barriers to trade, institutions, externalities, and so on, markets might easily provide the solution. Markets would then accurately factor in the extra costs deriving from fossil fuels from emitting CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs), so that all energy industries could compete on equal terms. In such a world, the fact that fossil fuel industries have had far longer to realize economies of scale and to develop mature technologies than most rival energy industries would not be important. However, this is not the world that we live in. Economists can help us compensate for some of the disadvantages that renewable energy industries and technologies face. Carbon taxes would, for instance, go some way toward putting a price on externalities resulting from GHG-emissions. The higher the tax on carbon emissions, the more competitive renewable energy would be, and the more the markets would favor renewables over other forms of energy.

However, ultimately carbon taxes are politically determined, and as such subject to a myriad of concerns. If one country sets its carbon taxes radically higher than other countries, energy-intensive companies may flee and set up shop abroad instead. Also, high energy and electricity prices are bad for the competitiveness of the industry in general, and it is bad for the purchasing power of common people. Thus, introducing, or indeed raising, carbon taxes comes at an industrial and economic, not to say a political cost, and one that politicians are often loath to bear. Doing the right thing for the long-haul is a distinctly bad political strategy if it costs you the next election.

But the lack of a global carbon tax set at an appropriately high level is only one of many reasons why renewable energy is not just replacing fossil fuels overnight. There are other structural constraints as well. Let us breeze easily past the more obvious ones: renewable energy has had far less time than fossil fuels to mature its technologies. Thus, in terms of learning effects, we expect technological progress in renewable energy to be faster than progress in established energy technologies. And in terms of economies of scale, the old and trusted industries have had far more time to realize these than have renewable industries.

The slightly more subtle bias is a political one. Institutional theory tells us that institutions create stability. They are the rules of the game. They lead to path-dependencies, and they act as bulwarks against radical change (e.g. March and Olsen, 1989; North, 1990; Olson, 1982). Consequently, institutional change also tends to occur at a far more glacial pace than technological change. New and upcoming industries frequently have different needs than established ones – in terms of knowledge and education, capital, linkages between academia, government and industry, patenting systems, and so on. The degrees to which these needs are met are crucial. A national system of political economy may be a good fit for one type of technologies and industries, but a distinctly bad one for other (and often rival) technologies and industries (e.g. Freeman and Perez, 1988; Gilpin, 1996; Nelson, 1995; Unruh, 2000). Quoting Gilpin:

... a society can become locked into economic practices and institutions that in the past were congruent with successful innovation but which are no longer congruent in the changed circumstances. Powerful vested interests resist change, and it is very difficult to convince a society that what has worked so well in the past may not work in an unknown future. Thus, a national system of political economy that was most ‘fit’ and efficient in one era of technology and market demand is very likely to be ‘unfit’ in a succeeding age of new technologies and new demands. (1996, p.413)

Thus, if the institutional system heavily favors old and established energy actors over new and promising, but ultimately vulnerable renewable energy actors, then this is something that markets will not pick up on. And so, if renewable energy is among the solutions for the future, energy-wise, industry-wise and climate-wise, the above points represent just a few reasons why markets do not automatically allocate enough resources to renewables. This also suggests why it is necessary to bring in the social sciences. The naïve take on renewable energy would be to simply think of this as a technological challenge, solved by natural scientists and engineers, letting technological progress run its course, and then within hopefully not too long, renewable energy technologies would be so efficient and sophisticated that they can compete on equal terms with fossil fuels.

This is, however, a book on the political economy of renewable energy, suggesting that politics and economics are crucial to understanding renewable energy. Obviously this does not mean forgetting that there is a heavy technological component to the rise (or the failure) of renewable energy. Compared to other and more established energy technologies, renewable technologies still have a lot of maturing left before they are anywhere near revolutionizing the world’s energy supply. But this takes nothing away from the fact that in addition to technological constraints, there are economic and political constraints affecting the prospects of renewable energy. Few areas are more cross-disciplinary than energy policy.

It is impossible to understand energy policy without understanding the linkages between the technological, the economic and the political. When renewable energy is not implemented in a country, this might be for technological reasons. But if we compare the most developed countries in the world, their ability to solve and work around technological obstacles is more or less the same, and so if one country manages to solve its technological problems, most others could follow suit. Then, there might be economic problems, typically as in renewables being too expensive, but many of the economic constraints faced by different countries also resemble each other. And then there are the political problems, and the political constraints, which are often the hardest to penetrate – because politics regularly operates according to a different logic, one that involves stakeholders, vested interests, institutions and institutional biases, as well as path-dependencies and inherited organizational and institutional cultures and quirks that are country-specific and where the experiences of one country cannot always be transferred to any other.

Renewables or bust?

So, are there no realistic or credible alternatives to renewable energy? Is renewable energy so important because it is the only current answer? The answer is not at all straightforward, but let us look at some of the alternatives.

Let us start with the default solution, which is simply more of the same. Granted, whether or not peak oil is upon us, there is no immediate danger. The world’s proved oil reserves have kept on increasing, especially if we also take unconventional sources into account, and the current drop in oil prices strongly suggests that the world is not running out of oil overnight. Instead, it is rather a matter of how eagerly we pursue the remaining resources, open up new areas for exploration, the extent to which new technologies can help us in exploiting resources that in the past used to be technologically unfeasible, and the extent to which new technologies can help us to extract a higher percentage of petroleum from existing wells. So, to an authority such as Daniel Yergin (2011) – co-founder and chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates and a Pulitzer Prize winner – the world is still awash in oil. We may be approaching a production plateau, but no peak. Reserves have never been greater, and pretty much the same goes for production levels (Yergin, 2011, p.239)!3

Others are not equally sanguine. Michael Klare (2012a, 2014) – professor at Hampshire College and the author of a number of highly influential books on oil and energy – forcefully states that while it is technically true that we are awash in oil, the days of ‘easy o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Japan: No Structural Change, Save for a Structural Shock? Vested Interests Pre- and Post-Fukushima

- 3 China: No Energy Transformation, but Full Speed Ahead. Or ?

- 4 The US: Renewable Energy Doing (Reasonably) Well. Despite the State or Because of It?

- 5 Germany: At a Crossroads, or Social and Political Consensus Setting It on a Course for Structural Change?

- 6 Denmark: An Energy Transformation in the Making? Wind Power on the Inside of the System

- 7 Norway: A Petro-Industrial Complex Leaving Little Room for Structural Change?

- 8 Conclusions

- Notes

- References

- Index