eBook - ePub

Sexuality and the Gothic Magic Lantern

Desire, Eroticism and Literary Visibilities from Byron to Bram Stoker

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sexuality and the Gothic Magic Lantern

Desire, Eroticism and Literary Visibilities from Byron to Bram Stoker

About this book

This fascinating study explores the multifarious erotic themes associated with the magic lantern shows, which proved the dominant visual medium of the West for 350 years, and analyses how the shows influenced the portrayals of sexuality in major works of Gothic fiction.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sexuality and the Gothic Magic Lantern by D. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sex and the Ghost Show: The Early Ghost Lanternists

Georg Schröpfer and Philipsthal the showman

Georg Schröpfer (1730–74), an ex-waiter, ex-Hussar and practising Freemason, opened his coffee-house around 1761 in the Klostergasse, Leipzig. Yet the business was not profitable and in order to make ends meet, Schröpfer branched out into providing a séance involving the summoning of ghosts. These sessions actually involved projections from a hidden lantern.

First, Schröpfer gave a verbal introduction to his ‘rite’, a speech sprinkled with Masonic and Cabalistic references.1 The audience was then led into the room of the séance, a chamber where the showman commanded the spirits to appear before him, and suddenly a fog rose from the floor. Images of apparitions were projected from a hidden magic lantern onto this smoke, the movement of which gave them the appearance of life. These visions were accompanied by a clattering: blows against the door of the room, ringings and hellish ‘hisses, wheezes and whistles’.2 In later shows, the piercing tones of the glass harmonica (a musical instrument containing a glass spindle turned by a treadle and played with moistened fingers) were to join these sound effects. Schröpfer went on to exhibit his ghosts in many other settings, including Dresden where, as a prelude to the main attraction, he led his guests down gloomy corridors to disorientate them. Schröpfer’s spectacle spawned many imitators.

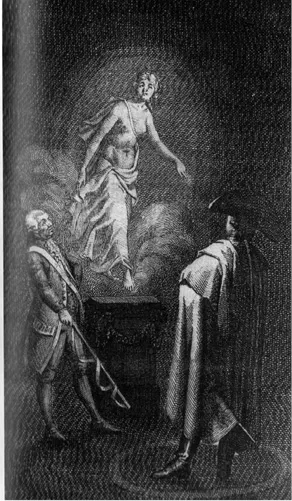

We know that live women actors were involved in Schröpfer’s shows because one of the observers remarked on a participating actor’s obvious state of pregnancy and another’s wearing fashionable buttoned ladies’ shoes. We can also deduce that some phantoms at Schröpfer’s and his imitators’ séances were female spirits shown in dishabille. An engraving in Karl von Eckharthausen’s Aufschlusse zur Magie (1788–91) reveals a typically voyeuristic scenario (Figure 3). Eckharthausen was a Bavarian scholar, mystic and lanternist who had mounted his own phantasmagoric displays and had actually known Schröpfer, which perhaps hints that the rather titillating engraving depicts the nubile kind of spirit familiar in such projections.

Figure 3 Engraving from Karl von Eckharthausen, Aufschlusse zur Magie (1788–91)

The engraving depicts a lady draped in a classical cloak which, it seems, barely covers her and exposes her breasts and idealised, well-toned stomach; this fair-haired apparition is shown treading the smoky air above a garlanded pedestal (perhaps a gravestone or shrine). With down-turned arms, she looks out of the picture frame at the viewer. A male master-of-ceremonies or necromancer (his jacket resembling military uniform) seems to gesture with his beribboned staff or pointer which tilts suggestively down from his crotch. The slant of this staff is visually echoed in the angle of a sword emerging from the cloak of another masculine observer whose back is turned to us. Has this stoutly booted and dominant figure who stands inside a magical circle commissioned this ceremony? Is this woman his deceased wife or lover – if so, why does she stand exposed in archaic costume while the men wear contemporary dress? The cloaked viewer’s posture – he seems to stand hands-on-hips – is redolent of a powerful male desire to probe the outer reaches of human knowledge, here incarnated as this radiant spectral woman. His expression is hidden from us but his head is turned directly towards the woman’s bared abdomen, and the signifying weapon, the sheathed tip of his sword, extrudes from his cloak in a display of phallic erotic fixation.

After Schröpfer’s sudden suicide, it was left for the showman called Philipsthal or Philidor to take up the mantle. Philipsthal travelled Europe with a show called his Geisterscheinung or ‘Ghost-shining’ to introduce magical conjuring tricks, a physics demonstration and even an orchestra into the ghostly repertoire of his lantern show.3 With his soubriquet, ‘Professor of Physics’, and scientific experiments inherited from a real ex-science teacher – the showman Giovanni Pinetti – Philipsthal toured the capitals of Europe attracting large, if sometimes sceptical, audiences.4 It was Philipsthal who, in Paris in 1792, first gave his phantom show the title phantasmagorie.5 Whilst in the capital, he also offered to resurrect ‘all the illustrious dead’, to ‘evoke at will the shade of any person that might be requested’.6 This was managed by asking the relative of the deceased person to provide a drawing or print of the person’s likeness; Philipsthal would then have a glass lantern slide of this image created for projection.

Raising dead mothers

This offer to ‘resurrect’ the dead was a brilliant if risky strategy. In the context of Paris, though, the risk to the showman who ‘raised’ the dead could not be more acute. This offer certainly brought the showman new admirers because it bolstered the bogus connections between the phantasmagoria and necromantic magic and also involved the intimate lives of members of the audience and memories of their deceased loved ones in a public display, the show almost acquiring the aura of a Spiritualist séance or mediumistic reading 50 years before these appeared. Further, to offer to resurrect, even temporarily, dead mothers and wives touched upon a most powerful psychological reflex in this patriarchal society. It is to be remembered that the French revolutionary authorities had at first flirted with and then abandoned ideas of proto-feminism. In those countries that were to host the aggressively capitalist and burgeoning industrialist economies of north-west Europe, the roles played by the majority of women were often severely circumscribed. It is also clear (as soon as parish records began to be kept in Britain in the 1860s) that the rates of maternal mortality in childbirth could be as high as 1 in every 12 mothers at peak periods.

Gothic novels and the ‘Graveyard’ school of poets had dramatised this complex of suppression and trauma in the recurrent themes of missing and dead mothers and the phenomenological space created by loss. Drawing on primal fears, this space was often filled in Gothic novels by that which, George E. Haggarty, in discussing Radcliffe’s The Italian, calls ‘an erotics of loss’:

Ellena is attracted to a disembodied voice, albeit a very beautiful one, and a feeling of other-worldly melancholy. She identifies with this sound, and she also feels the desire to put a face to all this wealth of sensibility. As these sounds rush over Ellena, this first view of Olivia in the lamplight, this secret attempt to penetrate the veil, and the abject figure of Olivia’s stance, all suggest an erotic intensity that the brutality of this prison-like convent only intensifies. The love that grows between Ellena and Olivia could be described as an erotics of loss: unbeknownst to both of them, Olivia is the mother that Ellena lost to ‘death’ in childhood.7

‘Erotic intensity’ was indeed apparent in such fantasies but, as Elizabeth Andrews writes, because ‘The female was the object of consumption’, her own basic appetites were often ‘denied’. She was frequently depicted as ‘starved and starving’:

This also communicated the taboo of female appetite, a taboo that persists and changes within the Gothic as the female assumes the status of subject and the power to devour; she moves from being ethereal to bestial in the nineteenth century.8

These strains of artistic expression were to combine, later in the century, with the High Victorian idealisation of virtuous women and motherhood. In their own spheres, women were beatified in the subject of Coventry Patmore’s poem ‘The Angel in the House’, and yet also vilified and demonised if they fell away from socially sanctioned tenets of respectability. Carolyn Dever’s Death and the Mother from Dickens to Freud: Victorian Fiction and the Anxiety of Origins provides a viable framework for the consideration of Dickens’s mawkish idealisation of deceased mothers.9 Yet, as we have hinted above, attempts to promulgate the purity of missing mothers also often took the form of a paradoxical denial of female sexuality. Such negation proves all the more problematic in relation to the urge realised in attempts to recover or revivify the mother’s image. This cathectic quest is, at least in part, Oedipal and therefore breaches taboo areas of discourse by default, engaging with the mother’s denied (and hence demonic) sexuality. In Jungian terms, the drive to recover the dead mother can also operate as a quest to discover the anima, the female side of the male. A composite figure like the Bleeding Nun of Lewis’s The Monk and Jonathan Harker’s lust for female demons in Dracula both serve as manifestations of these drives based on psychological denial.

Philipsthal finally took the necromantic associations of his show much too far and projected a slide of Marat in the form of a demon at the height of the Parisian Terror, a very dangerous gaffe. He was forced to make a hasty exit, thus leaving the stage free for competitors, amongst them the ingenious E.-G. Robertson, whose spectres would draw in the crowds at the Capuchin convent.

The lantern novel

In March 1786, Philipsthal arrived in Groningen fresh from his success at the Hôtel des Menus Plaisirs du Roi, Versailles. It will be remembered that it had been in this latter milieu nearly 70 years before that magic lantern slides had been employed extensively in erotic entertainments and pornography.

It is over this period, as Philipsthal returns successively to Holland, Germany and Austria, that Friedrich Schiller starts to write The Ghost-Seer (appearing in several instalments from 1787 to 1789 in the journal Thalia). The rituals employed accompanying the hidden lantern show in The Ghost-Seer recall the lantern-of-fear shows of Georg Schröpfer; it is clear also that Schiller moves beyond the more circumscribed repertoire of the Leipzig showman, to a more complex set of visual associations. There had been a flurry of literature addressing magic lantern shows in the early 1780s and Schiller definitely knew of Johann Karl August Musäus’s very popular Volksmärchen der Deutschen (German Folk Tales) (1782–86), where lantern trickery is revealed in the context of local nobility and a woman of mixed human and elfin ancestry who runs the show. The darker side of lantern illusionism is evoked here and this milieu might well have influenced Schiller:

The Lady Bela had the fewest adherents, for her heart was not good, and she often used her magic lantern to make mischief. Nevertheless she had inspired the people with such fear, that no one ventured to object to her for fear of rousing her vengeance.10

By April 1791, Philipsthal was in Vienna with his ‘Schröpferische Geister Erscheinung’ (‘Schröpfer-esque Ghost Phenomena’) and, by Christmas of the same year, he had augmented his show with a dance of the witches and the ‘fairies of all ages’.11

In Schiller’s novel we are told of three lantern shows masquerading as necromantic séances and these culminate in the vision of a living woman posed in a scene strongly reminiscent of a lantern tableau for the delectation of a male observer:

No! Up until that moment I had never really seen the fair sex! [...] the sun fell on this apparition. With inexpressible grace – half kneeling, half prostrate – she had thrown herself at the foot of an altar: the most striking, the loveliest, the most perfect outline, unique and inimitable, the most beautiful profile in the whole of Nature [...] the amazement caused by my first sight of her gradually gave way to a sweet emotion [...] She must be mine.12

These are the words of Schiller’s enthralled prince on seeing an anonymous young ‘apparition’ in a Venetian church. Though there were, as I’ve described, many novels which mentioned magic lanterns, The Ghost-Seer is the first major novel where lantern shows play important and explicit structural roles in the plot and subplots. In this scene, Andrew Brown translates Schiller’s ‘Gestalt’ (feminine: shape or form) as the word ‘apparition’, thus making it identical with the lantern’s false projections earlier in the story. It is an inspired translation because the woman’s form is being used in exactly the same way as the ghostly apparitions in the previous three lantern shows.

A same-sex milieu

Schiller’s The Ghost-Seer opens at carnival time in Venice and is narrated by an old army friend of a Protestant German prince who shares his adventures. At the opening of the tale, the prince has a ‘restricted allowance’ and so travels quietly with ‘Two gentlemen on whose absolute discretion he could fully count’.13 He has ‘shunned pleasures’ and at the age of 35 has withstood the ‘allurements of this voluptuous city’ and, most tellingly perhaps, ‘The fair sex had [...] remained a matter of indifference to him,’ as is also the condition of his army companion who doesn’t know a ‘single lady’ of the city.14 John Lauritsen discusses what Jack Gumpert Wasserman has written of the unique attractions of Venice for homosexuals:

First, and certainly foremost was the absence of all criminal and civil laws proscribing sodomy. Wasserman’s other five reasons concern associations with the culture of antiquity, a historically close connection with Greece, the ‘topography of Venice’ (which ‘provided unparalleled opportunities for clandestine meetings’), and the artificiality or magic quality of Venice. Wasserman describes the Venetian Carnival, in which gay men exuberantly took part.15

Schiller’s narrator tells us that ‘Deep seriousness and dreamy melancholy were ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Sex and the Ghost Show: The Early Ghost Lanternists

- 2 Byron: Incest, Voyeurism and the Phantasmagoria

- 3 Brontë’s VilletteVillette: Desire and Lanternicity in the Domestic Gothic

- 4 Le Fanu’s CarmillaCarmilla: Lesbian Desire in the Lanternist Novella

- 5 Lanternist Codes and Sexuality in DraculaDracula and The Lady of the ShroudThe Lady of the Shroud

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index