eBook - ePub

Japan and Reconciliation in Post-war Asia

The Murayama Statement and Its Implications

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Taking a comparative approach and bringing together perspectives from Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan, this volume considers former Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama's 1995 apology statement, the height of Japan's post-war apology, and examines its implications for memory, international relations, and reconciliation in Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japan and Reconciliation in Post-war Asia by K. Togo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Historical Role and Future Implications of the Murayama Statement: A View from Japan

Kazuhiko Togo

Abstract: The Murayama Statement of 1995 was the pinnacle of Japan’s apology for its wrongdoing before and during World War II. The position it put forward has been inherited by all subsequent Japanese cabinets. This chapter analyzes the holistic and unconditional character of the Murayama Statement, in which Japan as a nation was held responsible for its past colonial rule and aggression. It then clarifies this position by comparing the statement with West German president Richard von Weizsäcker’s 1985 speech on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the end of World War II. It subsequently deepens the analysis by looking at the work of Karl Jaspers and Daisetsu Suzuki in relation to the statements by von Weizsäcker and Tomiichi Murayama, respectively. Finally, the severe criticism of the statement by elite diplomat Ryohei Murata and others on the right, as well as by left liberals, is explained. The chapter concludes with concrete policy suggestions for strengthening Japan’s position on reconciliation with Asian and other countries.

Togo, Kazuhiko, ed. Japan and Reconciliation in Post-war Asia: The Murayama Statement and Its Implications. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137301239.

The statement by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama on August 15, 1995, is generally seen as the most unambiguous expression of Japan’s contrition since World War II. This chapter is based on the premise that there are certain universal issues of moral responsibility from which states and their leaders cannot escape. The definition of an objective criterion by which they can be measured is complex, but I believe that global society is slowly but surely moving toward adherence to these moral responsibilities. Thus Japan should face and come to terms with the pain it caused other nations during World War II, and in this context the Murayama Statement represents the pinnacle of Japan’s post-war apology.

In a previous paper (Togo 2011), I looked at Japan’s post–World War II settlement of war-related issues, including the issue of wrongdoing and apology. This settlement occurred primarily through international treaties such as the San Francisco Peace Treaty. However, after the end of the Cold War, when the topic of war memory and apology reemerged in international forums, the 1995 Murayama Statement was instrumental in synthesizing the position of the Japanese government on historical recognition and on reconciliation with Asian and other countries. If ever the Japanese government’s recognition of history has been expressed voluntarily and unambiguously, following the acceptance of the judgments of the war crimes tribunals prescribed in Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, it was in the Murayama Statement.

In view of the importance of the Murayama Statement, one is struck by the lack of serious study devoted to it. What are the major characteristics of the statement? What are its unique features, and how does it compare with other statements made in other countries that fought World War II? This chapter addresses these questions through a philosophical, political, and legal analysis of the statement, and through comparison with the experiences of other countries, particularly Germany. Since the chapter is concerned with adherence to universal moral responsibilities, much emphasis is placed on the thoughts and views of Richard von Weizsäcker and Karl Jaspers. Through this analysis, I attempt to define Japan’s future policy in terms of facing its role in recent history and ultimately achieving true reconciliation with the Asian and other countries.

Major characteristics of the Murayama Statement

Although the Murayama Statement should be analyzed in its entirety, usually only the key section is addressed:

During a certain period in the not too distant past, Japan, following a mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war, only to ensnare the Japanese people in a fateful crisis, and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations. In the hope that no such mistake be made in the future, I regard, in a spirit of humility, these irrefutable facts of history, and express here once again my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology. Allow me also to express my feelings of profound mourning for all victims, both at home and abroad, of that history.1

I begin my analysis of the Murayama Statement from the perspective of who perpetrated the wrongdoing, the nature of the wrongdoing, and the response to this wrongdoing, and then move on to address unanswered questions of responsibility and reconciliation.

First, who perpetrated the wrongdoing? In other words, who carried out this “mistaken national policy”? The subject here is “Japan,” and the primary distinctive feature of the Murayama Statement is the clear affirmation that Japan, as a state, in its entirety, pursued the mistaken policy. There is no further qualification, such as “Japanese leaders” or “Japanese militarists” or even “the Japanese people.”

Second, what was the nature of the wrongdoing? In other words, what was the content of the “mistaken national policy”? It was “colonial rule” and “aggression.” This is another distinctive feature of the Murayama Statement: the clear and holistic description of the nature of the acts involved. A comparison with the Resolution to Renew the Determination for Peace on the Basis of Lessons Learned from History, adopted by the Diet (the national House of Representatives of Japan) on June 9, 1995, clearly demonstrates the unconditional character of the Murayama Statement:

The House of Representatives resolves as follows:

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, this House offers its sincere condolences to those who fell in action and victims of wars and similar actions all over the world.

Solemnly reflecting upon many instances of colonial rule and acts of aggression in the modern history of the world, and recognizing that Japan carried out those acts in the past, inflicting pain and suffering upon the peoples of other countries, especially in Asia, the Members of this House express a sense of deep remorse.

We must transcend the differences over historical views of the past war and learn humbly the lessons of history so as to build a peaceful international society.

This House expresses its resolve, under the banner of eternal peace enshrined in the Constitution of Japan, to join hands with other nations of the world and to pave the way to a future that allows all human beings to live together.2

This reads almost like a scholarly description of historical events. The “colonial rule and acts of aggression” cannot be understood as acts that were perpetrated by the Japanese alone, because they were common at a specific stage of world history. The resolution described this as an objective fact, saying that Japan was part of it. The Murayama Statement displays none of this relativism: it focuses solely on Japan’s acts, without passing any judgment on the acts of other countries.

Jane Yamazaki clearly sees the unequivocal and exclusive nature of the historical recognition in the Murayama Statement: “In Murayama’s apology, apologizing for ‘aggression’ and ‘colonial rule’—accusations that could be leveled against many countries—allowed Japan to take the high moral road of having rejected militarism and colonialism when others had not. Strong condemnation of the wrongdoing is the hallmark of this kind of apology” (2006, 110).

Third, how does Murayama say Japan should respond to this wrongdoing? In other words, what should be done? “I express here my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology.” Here again, the expression is straightforward and unconditional. In contrast to the resolution adopted by the House of Representatives, which mentions only “deep remorse,” the Murayama Statement is an unequivocal apology.

The Murayama Statement also sets out concrete policy objectives, both before and after the key section quoted above. The preceding section outlines how

the Government has launched the Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative—to support historical research—in the modern era between Japan and the neighboring countries of Asia and elsewhere; and rapid expansion of exchanges with those countries. Furthermore, I will continue in all sincerity to do my utmost in efforts being made on the issues arisen from the war.

The section following the key paragraph quoted states that “Japan . . . must eliminate self-righteous nationalism, . . . [and] advance the principles of peace and democracy.”3 It is a truism that Japan’s fundamental contrition and compensation were the result only of a network of international treaty obligations that started with the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

But then comes the key question of “responsibility.” Who should be considered responsible for past colonialism and aggression, and how should the present generation view their responsibility? Murayama did not use “responsibility” as a key word, but the fundamental concept he developed seems to allow three interpretations: (1) The state itself was responsible for all the pain caused by colonialism and aggression. There is nothing that limits or conditions the state’s responsibility. (2) This applies to all who, in some way or other, participated in Japan’s acts during the period of colonial rule and aggression. There is, for instance, no notion of the leaders’ responsibility and their subordinates’ exemption from responsibility. (3) Given that Murayama was speaking about acts more than fifty years in the past, while still addressing the need for a concrete apology, it appears that this responsibility also touches the generation that did not participate in any act causing such pain in other countries. This holistic approach to the concept of responsibility is an important characteristic of the Murayama Statement.

The last question that needs to be addressed before we move to the next section is why Murayama made this statement. The speech tells us that Murayama’s primary motive was reconciliation with Asian and other countries that had suffered as a result of Japan’s acts. In terms of concrete actions to achieve reconciliation, Murayama stated: “I believe that, as we join hands, especially with the peoples of neighboring countries, to ensure true peace in the Asia-Pacific region—indeed, in the entire world—it is necessary, more than anything else, that we foster relations with all countries based on deep understanding and trust” (my emphasis). Fostering relations with all countries based on deep understanding and trust indeed appears to be the reason Murayama made his statement. The boldness of the statement seems specifically designed to achieve this purpose.

The Murayama Statement in comparison to Richard von Weizsäcker’s 1985 speech

After World War II Germany took a very different approach to responsibility and compensation than that adopted by Japan, which tried to resolve these issues through international state-to-state treaties. After the full extent of the Holocaust became known, Germany followed a policy of apology and individual compensation for all the victims of the Holocaust and other atrocities. In this respect, it is generally recognized that the most symbolic act of contrition was by Willy Brandt, who knelt down in December 1970 to honor and apologize to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The most conclusive statement of apology was made by Richard von Weizsäcker in the German Parliament on May 8, 1985, on the fortieth anniversary of Germany’s defeat in World War II.

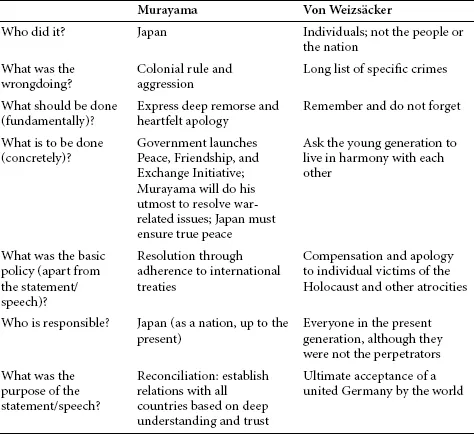

In comparing the Murayama Statement with this speech, I address again the three questions of who perpetrated the wrongdoing, the nature of the wrongdoing, and the response to this wrongdoing. I combine this with an analysis of responsibility and reconciliation—albeit in a slightly different order. (Table 1.1 provides a summary of the comparison that follows.)

First, what was the nature of the wrongdoing? In other words, how did von Weizsäcker perceive the nature of German wrongdoing before May 8, 1945? His speech starts with a long list commemorating “all the dead of the war and of the rule of tyranny: . . . the six million Jews, . . . the unthinkable number of citizens of the Soviet Union and Poland, the murdered Sinti and Roma, . . . the sacrifices of the Resistance in all countries occupied by us,” and so on (von Weizsäcker 1987, 43). The list is comprehensive, not limited to the victims of the Holocaust. It also does not exclude Germans as victims. The enumeration of the crimes committed vastly differs from the Murayama Statement, which mentions “colonial rule and aggression,” adopting a most holistic approach without specification.

Table 1.1 Comparing Murayama and von Weizsäcker

The next section concentrates on the Holocaust, describing the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis in detail. It uses phrases such as “the crime” and “the Holocaust” to refer to these acts (von Weizsäcker 1987, 47–48), and also describes how Hitler “wished to dominate Europe . . . by means of war.” In general, von Weizsäcker’s criticism emphasizes the scale and nature of the specific crimes discussed above (1987, 50), which again differs considerably from Murayama’s broad statement of “colonial rule and aggression.”

Second, I analyze the question of who perpetrated the wrongdoing in connection with the issue of responsibility. In a key section between his statements on the Holocaust and the domination of Europe comes the following sentence: “There is no such thing as the guilt or innocence of an entire people. Guilt, like innocence, is not collective but individual. . . . The predominant part of our present population was at that time either very young or indeed had not been born at all. They cannot acknowledge a personal guilt for acts which they simply did not commit” (von Weizsäcker 1987, 48). This is the fundamental difference between von Weizsäcker and Murayama, who took the holistic approach that Japan, in its entirety, was the perpetrator.

This, then, surfaces the issue of responsibility, which Von Weizsäcker also addressed: “All of us, whether guilty or not, whether old or young, must accept the past. We are all affected by its consequences and held responsible for it” (1987, 48). Probably the most famous theme of von Weizsäcker’s speech was that although present-day Germans were not the perpetrators, they are nevertheless responsible for the crimes committed in the past by a limited number of individuals. Von Weizsäcker’s position also helps to clarify Murayama’s position on the issue of responsibility, as described above. Without conditions, Murayama accepted the responsibility of Japan,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 The Historical Role and Future Implications of the Murayama Statement: A View from Japan

- 2 Political Apology in Sino-Japanese Relations: The Murayama Statement and Its Receptions in China

- 3 In Search of the Perfect Apology: Korea’s Responses to the Murayama Statement

- 4 Redeeming the Pariah, Redeeming the Past: Some Taiwanese Reflections on the Murayama Statement

- 5 Neither Exemplary nor Irrelevant: Lessons for Asia from Europe’s Struggle with Its Difficult Past

- Index