![]()

Part I

Materiality, Space and Practices: Definitions and Discussions

Key questions:

What is materiality? What is materiality in management and organization studies? How does one make sense of materiality and space at the level of everyday practices in society and organizations? Are instruments, artefacts, affordances and imagination relevant focuses to make sense of space and materiality?

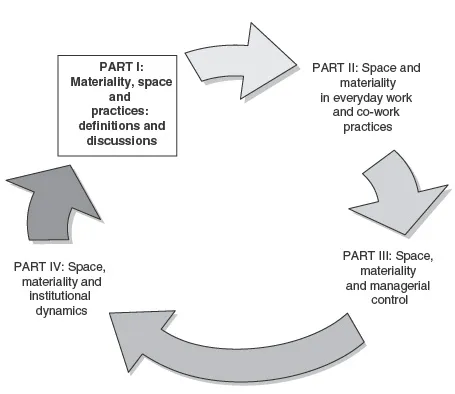

![]()

1

Living in the Material World

Andrew Pickering

Introduction

My topic is materiality and how ideas on materiality from my field – science and technology studies (STS) – might cross over into management and organization studies. ‘Sociomateriality’ (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008) is already an important topic in management and organizations, but I will try to widen the frame. We can start with technologies of the self, then turn to industry and technoscience, and finally explore an odd form of management which builds in the perspective that I want to develop. The overall idea is to multiply our sense of the many different ways in which matter is intertwined with us.

First we should get clear on what the problem is. The problem, as I see it, is that since Descartes, Western philosophy, social science and even commonsense have taken for granted a dualist ontology of people and things. We are different in kind from animals, machines and nature inasmuch as we have something special that the rest of creation lacks: souls, reason, knowledge and language. And this difference is also an asymmetry. We are the only genuine agents in history. We have will, intention, goals and plans, whereas non-humans are machine-like, predictable, passive, waiting for the imposition of our will. We call the shots. This sort of human exceptionalism, as I call it, is nonsense but it is the key to understanding the form that the human sciences take today (Pickering, 2008). Sociology since Durkheim has generated a fabulous range of resources for thinking about autonomous active human beings as if they were masters of a passive universe.

Challenging this picture is not as simple as one might hope. In my experience it entails a paradigm shift, in Thomas Kuhn’s sense. The trick, I would say, is to change our conception of agency in a way that enables us to come at the world from a new angle. We should stop thinking about agency in terms of will, intention, calculation and representation, and start thinking about it in terms of performance, in terms of doing things, things that are consequentional in the world. Performance is the place we should start from, not reason, language, representations and symbols. And the key point is that if one starts from performance, Cartesian dualism collapses. We humans are performative agents – we do things in the world – but so do rocks and stones, cats and TV sets, stars and machine tools. At the level of performance, we are the same as everything else; we are not different in kind. Furthermore, at the level of performance, we are constitutively engaged with our environment: we do consequential things to it, and it does things back to us, on and on forever in what I like to call an open-ended dance of agency (Pickering, 1995a). We are stuck, so to speak, in the thick of things – we can never step outside and take command as traditional sociology likes to imagine.

So the paradigm shift I have in mind moves in a non-dualist direction by emphasizing performance rather than will and representation and cognition, and by recognizing that performance densely and constitutively enmeshes us in the world rather than splitting us off from it. To throw in some more words, the dualist social sciences are ‘humanist’ in the sense that they find their explanatory variables exclusively in the human and social world, while the perspective that I associate with STS is instead ‘posthumanist’, decentring the human and foregrounding instead non-dualist couplings of people and things.

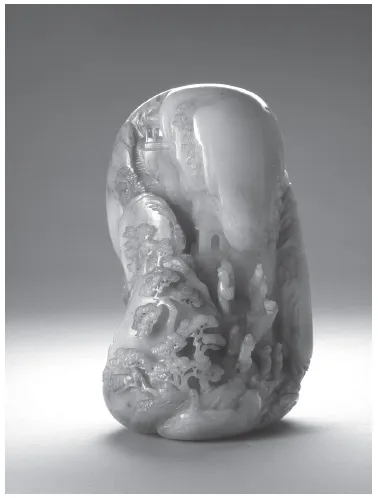

As a mnemonic, consider the jade sculpture shown in Figure 1.1. At the bottom right you can see some small figures, and in other places you can see traces of human constructions – an archway in the middle and a stairway towards the top. But these are minor parts of the overall composition, not the key elements of it: the trees, mountains and clouds are much more powerful and striking, and the people nestle amongst them. The vision here is of humanity as just a part of a larger world, and this sort of vision is, I would say, a necessary condition for finding questions of materiality and space, the concrete substrate of our being, interesting. And then we can note that this little sculpture is not Western. It is Chinese; it exemplifies what I think of as a Taoist ontology, not a Cartesian one.

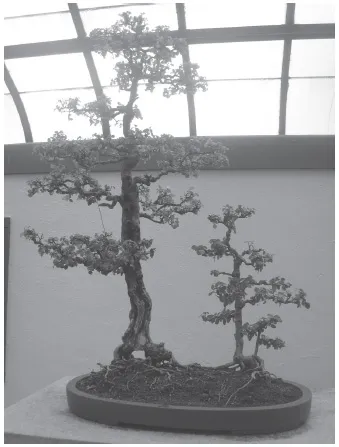

And to stay with the East, for a small but perspicuous example of how we are plugged into the larger social world, we could think about bonsai trees (Figure 1.2). In an obvious sense, keeping a bonsai tree is itself a decentred dance of agency, between the tree – a non-human agent – which continually grows new shoots in unpredictable places and directions, and a human agent who reacts to that, trimming the shoots here and there in pursuit of an emergent aesthetic, and so on, back and forth between the human and the non-human. Bonsai, then, can be a model for how we exist in the world in general, and this points us in one direction to the posthumanist analysis of a dense performative engagement with the world, and in the other to Taoism again, with its non-modern understanding of the world as endless decentred flows, transformations and becomings.

Figure 1.1 Jade Mountain, 1700–1725 AD

Reproduced by permission of Durham University Museums, Gift from Sir Charles Hardinge, DUROM. 1960.2205

But isn’t Taoism one of those premodern philosophies that the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment were supposed to have demolished? This turn to the East, which I want to take seriously, is a marker of the price to be paid for throwing in your lot with posthumanist STS. I think the Taoists got it right about how the world is, and we modern Cartesians have got it wrong.1

More than images and philosophies, we need examples of what is at stake in the shift to the posthumanist paradigm. Most directly, it is interesting and important to explore and appreciate the ways in which management and organizational forms are emergently mangled alongside the introduction of new technologies (and vice versa). But rather than enter into the existing literature on this (see e.g. Orlikowski & Scott, 2008; Jones & Rose, 2005; Barrett et al., 2011; Lynchnell, 2011), I aim here, as I said, to widen the frame, and I want to begin with technologies of the self.

Figure 1.2 Bonsai Tree. Credit: Jane Flaxington (personal picture)

The dualist conception of the self is that of a stable, reliable centre of the action, autonomous, calculating and rational, that one can appeal to as an explanatory variable. The great achievement of Michel Foucault was to show that this distinctly modern self, if it exists at all, is a historical creation, not the essence of humanity. In Discipline and Punish (1979), he showed how the materialities of architecture, partitioning space and organizing lines of sight, can function to transform inner states, making men docile, engineering a certain version of the modern self. The central insight of his book is that specific human selves are made in specific human/non-human assemblages. The phrase ‘technologies of the self’ comes from Foucault’s later work (1988) in which he explored ways in which people have worked on themselves to systematically transform their inner being. Often these have entailed purely mental disciplines. The Stoics, for example, tried to imagine themselves in the worst possible situations so that they could face up to them with equanimity if they ever really happened. But we can still think of this in terms of performativity. The self is multiple, and technologies of the self set up inner automatisms or machines that act as a check on other automatisms.

I take the idea of technologies of the self more literally and materially than Foucault. The counterculture of the 1960s, for example, deployed all sorts of material technologies in what we used to call ‘explorations of consciousness’. Sensory deprivation tanks, biofeedback set-ups, stroboscopes, dream machines and psychedelic drugs all figured as doorways to altered states. Very strikingly here, new selves and subject-positions emerged in performative interactions with material set-ups. In The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley described and explored a new relation to the world and his own inner being that went with his first experience of mescaline. And in his follow-up essay, Heaven and Hell, he argued that all mystical experience of unity with the divine depends on some such material technology, including, for instance, fasting, flagellation, chanting and meditation, as well as strobes (Huxley, 1956; see also Lilly, 1972; Geiger, 2003; Pickering, 2010).

Examples like these help us to see that far from being a stable given, the human self is itself materially produced and engineered. But one qualification is important. Technologies of the self are not causal in a linear sense. LSD elicits bad trips as well as good ones – the same molecules but very different effects. Emilie Gomart and Antoine Hennion (1999) once did a fascinating study of the ways in which drug users and music lovers construct specific set-ups – which they called dispositifs, following Francois Jullien (1999) – to optimize their experiences, tuning themselves, one could say, materially and socially, into an open-ended space of possibilities. When should you take this drug – in the morning or the evening? Alone or in company with other people? Alone or in the company of other drugs? And what should you do while taking it? Gomart and Hennion have a lovely quote from someone saying ‘I steal so naturally’ when on some drug I can’t remember.

Natalie Dow Schull’s (2005) study of digital gambling goes along the same lines. She explores the ways in which gamblers find their way into ‘the zone’ – a space of mindless detachment from the mundane world, characterized by a feeling of seamless flow. This is, of course, a sort of dualist separation from the world, but it depends, nevertheless, on all sorts of non-dualist material couplings. The gambling machine itself – an automated slot machine – is crucial. Nothing would happen without it. But many more levels of tuning are also involved. The gamblers learn to put paper cups on adjacent seats to keep other human beings away, and stick toothpicks in the mechanism so that one gambling episode follows automatically from another. And from the other side, engineers endlessly tinker with the hardware and software to help the gamblers entrain themselves to the machines more effectively. The machines are equipped to make possible drink orders and cash withdrawals without human intervention; the software becomes adaptive, speeding up or slowing down play in response to the revealed preferences of the gambler.

I can make two observations on this example and then we can move on. One is that gambling machines have a dual function: they are the pathway for gamblers into the zone, and, at the same time, they plug the gamblers into the circuits of capital. This inner/outer connection is probably always a feature of technologies of the self. The Stoic’s inner stability goes with the role of ruler of the outer, political, state. Inner calm and non-violent political protest hang together with meditation as the pivot. Explorations of consciousness were integral to the counterculture as a distinctive form of life. So matter here can be seen as helping to constitute both specific selves and the specific social structures with which they hang together.

Second, the gambling example (like bonsai) points to the concept of emergence. As I said, the machine causes nothing; it is not the explanation of the gambler’s behaviour. Instead, the gambler has to find out how to use the machine in practice, how to tune themselves into it. Likewise, the machines, and the engineers behind them, have to find out how to use the gambler. Nothing in this trajectory of coupled findings-out is given in advance. It is emergent in the brutal sense of not being predictable or even explicable in terms of independent variables. And just like the coupling of people and things, emergence is something which is hard for the Western imagination to take in. The shadow of the Cartesian machine still hangs over the social sciences. To find any inspiration for thinking about such processes you would have to look elsewhere: to biological notions of co-evolution, say, or further afield, to Eastern philosophy – the Taoist image, again, of the world as a place of endless decentred becomings.

We can leave the self behind and move from the micro to the macro and think about technoscience, the coupling of science, industry and the economy that we take for granted today and that seems to be the last hope of the West. As is well known, one of the first important examples of technoscience dates back to the second half of the 19th century and the dye industry: a whole series of synthetic dyes were discovered which were the foundation of a new industry and a new sort of chemistry, and the new industry and the new science grew together as a new sort of scientific/industrial assemblage (Pickering, 2005, 2012). The story is too rich to get into here, but I do want to suggest that it is, in a way, isomorphous with what I just said about technologies of the self.

We can start by noting the obvious. As Thomas Pynchon wrote in Gravity’s Rainbow (1975), ‘If you want to know the truth, you have to look into the heart of certain molecules’; the synthetic dye industry was absolutely dependent on emergent properties of matter, on how matter turned out to perform. The key event was the discovery of the dye called mauve, by William Henry Perkin in London in 1849, and the key point to note is that Perkin was not trying to produce a dye at all. He wanted to synthesize the antimalarial drug quinine, and it just so happened that when he mixed certain chemicals and processed them in a certain way he arrived at a substance that could dye cloth a pretty colour. Here again then we find brutal emergence in the domain of matter, something completely unpredictable in advance that was immensely consequential for human history. And similar emergent material phenomena marked the whole history of this industry. It was important, for example, that mauve was not alone. Experimenting with different chemicals, chemists succeeded in synthesizing an ever-expanding list of coloured substances that could serve as dyes. Emergent material phenomena here were absolutely central to the emergence of the world we live in now.

At the same time, it is important to think how these substances were drawn into the human world, and especially how they were transplanted from the laboratory into chemical factories. Scaling up their production proved to be non-trivial. Attempts to do so were dogged by explosions, and the destruction of lives and property. Again we would have to say that it just so happened that Perkin and others found ways to more or less safely scale up the process, cooling the reactants to prevent explosive boiling. They could have failed in this negotiation with the emergent properties of matter, and technoscientific dye production might never have happened. This is a point that has interested me a lot recently. A century-and-a-half after Perkin, chemical factories still explode. So we have this paradoxical situation in which the social sciences resist seeing that matter has agency, while, out there in the real world, the typical problem is to contain material agency, to keep it in check and channel it, to shield ourselves from it. Disastrous failures like Deepwater Horizon and Fukushima can serve to bring this point home. And much human labour is, in fact, devoted to maintenance schedules and the like, which would make no sense without a recognition of the performative agency of matter that they try to keep in check, an attempt which necessarily, I would say, fails from time to time. Our entire world is built on this sort of chancy engagement with the material world. We live on performative islands of stability (Pickering, 2011a). The social sciences need to be able to get that into focus.

But what about science? We are taught to think that we have science to thank for technoscience, as if the science comes first and makes industry and the modern economy possible, A performative perspective suggests that this is a mistake. Perkin had no idea what he was doing when he synthesized mauve – or, at least, only a mistaken idea. And the blossoming of the dye industry was integral, in fact, to a transformation of chemists’ understandings of matter. Chemical theory struggled to keep up, trying to rationalize what had already been accomplished, and a good theory was one that could do that, and also help in some way in mov...