- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Gothic Child

About this book

Fascination with the dark and death threats are now accepted features of contemporary fantasy and fantastic fictions for young readers. These go back to the early gothic genre in which child characters were extensively used by authors. The aim of this book is to rediscover the children in their work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

First Steps

To understand the concept ‘gothic child’, the notion ‘child’ itself has to be cleared of its present-day meanings. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it is a necessary step that needs to be taken in order to avoid confusion and amalgamation by taking into account the changing face of childhood today and transposing it into a period which may have had a different conception of childhood, especially as concerns the age, rights and responsibilities of the child. Secondly, the rediscovery of this concept, as it is reflected in the gothic writings of the period 1764–1824, is hardly possible without taking into consideration the reality of the times. For instance, today’s readers may be shocked if an author refers to the child with the pronoun ‘it’. But it was not unusual in the eighteenth century and there are numerous reasons for the practice. The Convention on the Rights of the Child is a recent development and it is important to remember that in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century worldview, it is the adult (parent or guardian) who decided on these rights. What is more, what we call ‘rights’ today was then referred to as ‘obligations’ or ‘duties’ and these were integrated into a broader, religiously inflected outlook on the child’s role.

When the word ‘child’ is used in the following pages, it always points to the meaning that can be elicited from the gothic genre from 1764 to 1824. All concepts pertaining to the semantic field of ‘child’, including words used as synonyms and meronyms within the works listed in the bibliography, have been used for this study. The singulars and plurals of ‘infant’, ‘babe’ and ‘baby’, ‘boy’ and ‘girl’, ‘daughter’ and ‘son’, ‘youth’ and in some cases ‘great youth’ or ‘very young’ when they refer to childhood or to the experience and state of being someone’s child have all been included, alongside ‘childhood’, ‘infancy’, ‘childish’, ‘boyish’, ‘like a child’ and ‘childlike’.

The first issues that need to be addressed are linked to the identity, place and representation of the child in the gothic novel. Who is called a ‘child’? How is the word used? Is it applied to young persons only and if so, what is their age? Are there any other meanings attached to it? This chapter begins with an analysis of the term ‘child’ and its usage and then continues with a discussion of the child’s place within the gothic narrative. The second part of the chapter intends to define the function of the child within the gothic plot and the last part deals with the appearance, representation and characterisation of the child in gothic.

‘Child’ in 1764–1824 Gothic

In the novels belonging to first-wave gothic, the term ‘child’ is applied to an immense array of characters – it is a mark of filiation; it denotes states of dependency (affective or financial); it is applied to persons of unstable perception and understanding as well as to characters of both sexes lacking affective maturity; to those who are vulnerable or helpless; to those who are under legal guardianship; and to those subjected to parental will and authority regardless of their age. When calling someone ‘child’, the narrator usually takes into account that person’s innocence or lack of knowledge, their potential for development or their intellectual pliability. It appears that everyone can be a ‘child’ in gothic at any given point in the narrative. In fact, the period of childhood frequently extends to cover adulthood, as we find in the arguments of the Cambridge latitudinarian Thomas Rutherforth. In Institutes of Natural Law (1754), he ‘[makes] use of the word childhood in a more loose sense, than is commonly used, to signify all the time of a persons [sic] life, that passes, whilst his parents are living’ (Rutherforth, 161). Thus, when we are not dealing with babies and young children, we are dealing with someone’s child (a daughter or a son) or with an adult’s reminiscences of childhood. And most gothic heroes and heroines remain children until that moment of inexorable certainty when they are forced to look at a parent’s dead body. This is precisely what happens in Summersett’s Martyn of Fenrose (1801) when two soldiers decide whether the body of the father should be presented to his son:

‘Oh, it will be too much for the gentleness of his nature! Spare him [ ... ] from a sight so distressing.’

‘[I] have prepared him for the occasion [ ... ] when I bring him to the body of Alwynd, and point out his many gashes, the tempest of the soul will vent itself freely, and probably be soon succeeded by a calm of long continuance.’ (Summersett, 84)

The child is thus supposed to mourn by carefully observing the bruised corpse. Instead of trauma, the narrator sees in this an occasion to ensure a peaceful adult life for the descendants. Similarly, Bonhote, Carver, Lathom and Ireland present readers with scenes of distress where children of all ages attend funerals, sleep next to corpses or witness the deaths of their parents. A striking example is young Laura, in Oakendale Abbey (1797), whose parents are murdered in India. Adopted, she sees the head of her second father on a spike, carried by a crowd of bloodthirsty revolutionaries. Another example is the orphan Huberto in Ireland’s Gondez (1805) who is imprisoned at the age of seven; he watches over his dying stepmother and sleeps on her corpse. This is how the gothic child grows up. Contemplation of parental death and the observation of public or private mourning or execution rituals constitute a rite of passage for the child and are thus encouraged.

But even after that rite of passage, at the approach of adulthood, the usage of the word ‘child’ remains vastly extensible. Accordingly, examples range from the helpless babe metaphor to the childlike innocence of the heroine and the childishly capricious villain. The gothic novel also pays considerable attention to adult children in relation to the legal, social and religious status of their parents. Often, the child is a projection, an idea or a memory in the adult’s mind. The child’s age is therefore variable and frequently difficult to determine. Very few authors mention the exact ages of those they choose to call children. From the unborn child, through early babyhood to adolescence and adulthood, ‘child’ becomes an epithet, applied to both young and old, to signify belonging, to mark social status and the state of subordination or to stress age differences. Furthermore, the word ‘child’ has both positive and negative connotations in a variety of contexts, and some of them coexist (frequently in the same novel) in apparent contradiction. To some narrators the child is a burden. For others it is a blessing. Some authors confer to the concept a transcendental dimension and situate it high or low on the spiritual scale; they see in the child an angel or a demon, and in many cases transform the figure into a potent metaphor. Many authors use the child to analyse domestic, social or political matters. For some, the child obeys and is subordinate to the father. For others, the child rebels and overthrows the rule of the father. Thus, the figure of the child in gothic is both a subject and a ruler, subordinate and subordinating. The child can be a small, insignificant, weak element of the plot but it can also govern all events and determine the behaviours, decisions and actions of adult figures. And if there is a clear-cut rule about the nature of the child in gothic, it is that the child will invariably appear in every novel. Often, this is done in such a way as to leave it partly in the shadows. Frequently, one has to seek the child between the lines and in the hazy margins of the text in order to find it.

For instance, the titles of most gothic novels published in the period 1764–1824 give us no indication about the characters we may expect to find within. Titles like Castle of Beeston (1798), The Castle of Santa Fe (1805) or Forest of Montalbano (1810) refer directly to the building or the place name. The most obvious explanation is that this custom originated in the ruin exploration craze and the growing desire for historical exoticism and travel which seized eighteenth-century readers. Other titles were chosen with the aim of attracting amateurs of the horrific and supernatural with a touch of mystery and the promise of exciting love affairs. But upon a closer analysis of the dense body of gothic novels and romances published throughout the period, there can also be found authors who have used a child in the title or who refer to a child with an indirect mention of family relationships, parentage, filiation and heritage. Walpole’s Mysterious Mother (1791), Parsons’s Girl of the Mountains (1797), Roche’s Discarded Son (1807) or Pickersgill’s Three Brothers (1803) are among these. Authorial attachment and interest in exploring childhood, in studying the characters of parents and their children or in using the child as a symbol and metaphor are clearly revealed in titles like The Children of the Abbey (1796), The Mysterious Pregnancy (1797), the adaptation Edmond Orphan of the Castle (1799), The Haunted Castle, Or, the Child of Misfortune: A Gothic Tale (1801), The Children of the Priory (1802), The Child of Mystery (1809), The Child of Providence; or, the Noble Orphan (1820) and Gwelygordd, or, The Child of Sin (1820). One thing is especially interesting in the lengthily titled novel The Gothic Story of Courville Castle; or, the Illegitimate Son, a Victim of Prejudice and Passion: Owing to the Early Impressions Inculcated with Unremitting Assiduity by an Implacable Mother; whose Resentment to her Husband Excited her Son to Envy, Usurpation, and Murder; but Retributive Justice at Length Restores the Right Heir to his Lawful Possessions (1801). The word ‘child’ is not used but a whole network of images deal with one central issue, that is, an illegitimate child is begot. The title deals with family relationships and also opposes the ‘right heir’ to what one assumes is ‘the wrong heir’. This corresponds to a binary opposition between the good child and the bad child, a conflict that we find at the heart of gothic from its very beginning.

Clara Reeve’s The Old English Baron (1777–78) contains good examples of the heterogeneous usage of ‘child’ and also of this very particular confrontation between right and wrong heirs, and good and bad children growing up together. The novel has the merit of not being the first of its kind and, therefore, its author had ample time to think over the plot, the characters, the setting and the outcome. The use of children and heirs is, therefore, far from accidental. Reeve borrowed themes, motifs and character traits from Walpole and from Hutchinson’s Hermitage (1772). In the attempt to improve what she thought imperfect, she modified the location and settings, and the family configuration; she combined the dramatic excess of the Continental Otranto with the chivalric Romanticism of the very British Hermitage and, meanwhile, made some mistakes herself. However, her decision to keep the idea of an extended family and develop issues of adoption, fratricide, sibling rivalry and usurpation by giving the leading role to an orphan and a twice-adopted child is the principal reason why Reeve’s work is as gothic as those that precede it. No doubt, the setting is medieval, Romantic and gloomy, and there are forests, castles and secluded shacks. But these are not the objects of principal interest. It is the grown-up child and heir that becomes the object of central focus. The idea that the foundling can return and claim back his due defines the novel’s action exactly as it did in Otranto.

A notable example from Reeve’s text is the use of the expression ‘big with child’ (Reeve, 6, 49) instead of other conventional expressions such as ‘pregnant’, ‘far advanced in her pregnancy’, or even the frequently used ‘situation’ or ‘condition’. Consciously or not, when referring to advanced stages of pregnancy Reeve lays the stress not on the mother but on the child, and on the portentous role attributed to this child. Further, Reeve uses ‘child’ interchangeably with ‘my son’, ‘son’, ‘infant’, ‘babe’ and ‘offspring’ well over a hundred times on a total of 263 pages – that is, on every other page. Reeve uses ‘child’ for young persons of the age of 17, 16 and for children of unknown age below 16. These ‘children’ are brothers, sisters and cousins, most of them related by blood and never portrayed in detail. And then there is the detailed portrait of the twice-adopted child – Edmund – whose mysterious resemblance to a late lord finally legitimises him as the lost heir of the House of Lovel. The boys in Reeve’s narrative grow into men only after undergoing successive rites of passage – war, exploration and travel – which usually confront them with death. The lost Lovel heir, however, is constantly surrounded by adult men who protect him. He is continually referred to by the expression ‘child of’ (Reeve, 95, 144, 216) and ‘offspring’ (Reeve, 144) even in his adulthood. At first this is done to demean him in comparison to superior men of rank (he is a mere child) but then, ironically, it also raises him above them as the legitimate successor and future master (he is the child of a noble). The representative of the Catholic Church in the person of Father Oswald introduces a religious and spiritual dimension to the usage of ‘child’ to affirm and strengthen the elevated rank of the lost Lovel heir. Thus, the child becomes a figure of potential, a character who develops throughout the story and whose significance in the storyline is multifaceted – domestic, political and spiritual.

Reeve’s development of the child influenced later representatives of the gothic genre. We find the same systematic use of child characters in Lathom, Ireland, Lee, Radcliffe and Maturin, resulting in a progressive construction of a very complex notion. It is important to stress the fact that the practice of introducing children into the narrative is not limited to female authors. Probably due to the scale of their magnum opus, Maturin and Godwin produced some of the most striking child portraits in gothic. In addition, with the expansion of the genre, Wilkinson, Parsons, Roche, Dacre, Moore and Brewer contributed to the creation of a child-centred sphere that includes child mothers, childish or childlike heroines, child villains, peasants and a vast number of ‘children of’ – children of providence, children of nature, of labour, of misfortune, of mystery, of sorrow, children of love and children of God. This is sometimes carried to such extremes that almost any gothic character may become a ‘child’ or a ‘child of’ and, therefore, the function and place of that notion in the text gradually becomes a constant.

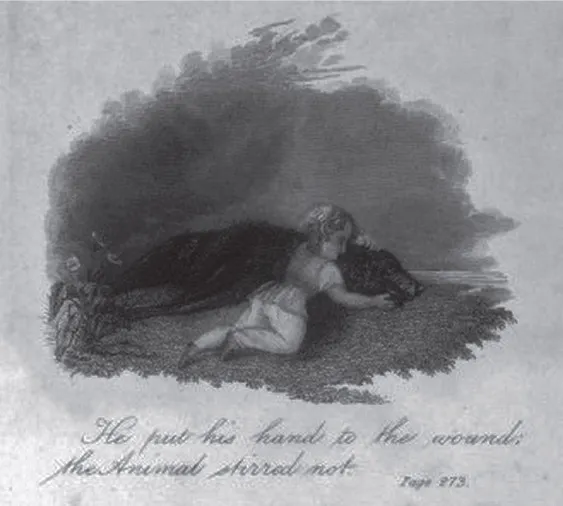

One of the illustrations of the 1831 edition of Godwin’s St. Leon (1799) contains a pencil-on-paper drawing of a child and his dog based on the events of the novel (see Figure 1.1). The effect achieved by the high angle adopted for the drawing is very similar to that of many gothic texts. They are attempts to look down upon a vulnerable, powerless individual, to evaluate their emotional and moral potential and to observe the most striking episodes from their life. Similarly, Maturin and Lewis employ the high-angle device (to depict a parent looking upon a sleeping/dying child) repeatedly and Ireland inverts it by changing the position of child and parent – an omniscient narrator looks down upon a child looking down at the corpse of his mother. The drawing in St. Leon summarises one of the founding principles of the gothic chain narrative and the place of the child in it – after telling the story of his own birth, childhood and youth, the narrator becomes a parent who takes care of and observes his own children. Thus, his life and further adventures are solidly tied to the child and he is bound to look upon and deal with the child figure at all times.

Figure 1.1 Frontispiece to William Godwin’s St. Leon, pen and ink on paper, drawing of a child and his dog, 1799.

The Child’s Place in the Narrative

Within the gothic novel ‘the voice of childhood is feeble’, writes Horsley Curties (Ethelwina, 168). Fashionable author and man of fashion with connections himself (see Townshend), he would later on write for children in Select and Entertaining Stories [...] For the Juvenile; Or, Child’s Library (1815). Curties’s perception of his favourite genre is indeed accurate. In many novels, the child’s voice is reduced to a barely audible whisper. The occasional, distant laughter of peasant ‘children at play among the rocks’ (Udolpho, 28) or ‘the feeble cry’ (Melmoth, 512) of an infant are among the few means of declaring a child’s presence. All those without a voice, those who cannot or do not speak in gothic are children, or in-fans. Furthermore, the child is commonly referred to with the pronoun ‘it’, denoting an absence of gender distinctions, which can only appear after the child is properly integrated into the world. This convention objectifies the child as if in support of the idea that the child is a character and a figure, a device, a symbol, and a characteristic with the help of which adult characters can be manipulated. In the novels of Cullen, Sicklemore, Brewer, Wilkinson and Lewis, to cite a few, the child is not always the narrator of its own story. More often, it is the adult omniscient or first-person narrator who tells about the child. For most authors, the child exists through the voice of the adult, as a directly observed figure (when adults care for or watch over children) or as a more or less distant memory – as an idea, a wish, a desire, a projection and a metaphor. Hence, ‘child’ in gothic is sometimes used to refer to a state of being but not always to a human being possessed of faculties and emotions. When not coming from the child, the voice of childhood belongs to the child within the adult. This is how the child in gothic acquires a preternatural, otherworldly aura of an omnipresent being not necessarily possessed of corporeality.

A broad classification of children in gothic encompasses two types of character. On the one hand, there are children who are constitutive elements of the Romantic landscape, who play a role of supporting characters or are mere accessories contributing to the general atmosphere. Dead babies, child corpses or skeletons and occasionally appearing peasant children are among these. On the other hand, there are children who participate in the plot, contribute to the creation of suspense and take part in the actions, becoming the main characte...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 First Steps

- 2 ‘Becoming as Little Children’

- 3 Experimenting with Children

- 4 Child Sublimation

- 5 The Political Child

- 6 The Gothic Child on Film

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Gothic Child by Margarita Georgieva in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.