eBook - ePub

Asian and Pacific Regional Cooperation

Turning Zones of Conflict into Arenas of Peace

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An exploration of why and how peace has gradually mitigated intense conflict in the Asia-Pacific region, this volume draws on case studies and multivariate quantitative analysis to test theories of peace and conflict regarding the region.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Asian and Pacific Regional Cooperation by M. Haas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Asiatische Politik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theories

After World War II, there was a belief that Europe could not abide yet another world war. Yet the division between the communist Eastern Europe and capitalist Western Europe meant that both were armed to the teeth, even rattling nuclear weapons as modern-day sabers.

Responses to the challenge differed. Division into two superpowers was the immediate reaction, but that kept the world in an uneasy suspense over who would prevail and where. A second response was reliance on the United Nations (UN) to mediate or at least to mitigate divisions, but the UN was divided between the Eastern and Western blocs of countries, and a third bloc of nonaligned states wanted attention directed toward them. Some envisioned a “United States of Europe,” but that meant dismantling sovereign states that had spent centuries guarding their borders from attack. A less ambitious plan was to bring about some economic and social unity through regional organizations without political unification.

A flood of academic writing developed to promote regional organizations in Europe. Leaders in Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, and the South Pacific found reasons to develop regional institutions as well. One of the reasons is that Chapter VIII of the UN Charter serves to integrate regional organizations into the world’s global polity. Very recently, one scholar has maintained that Chapter VIII permits regional intergovernmental bodies to act on security matters when the UN’s Security Council is deadlocked, provided that the Security Council is officially notified (Slaughter 2012). Thus, an analysis of how regional organizations handle interstate conflicts is vital to the maintenance of global peace and security today. Accordingly, this volume seeks to determine how regional organizations in Asia and the Pacific have turned zones of conflict into arenas of peace over the past five decades.

Chapter 1 in this section of the book summarizes several theoretical approaches. Chapter 2 applies cultural elements, sometimes left out of discussions by theorists who focus on Europe, to regional cooperation in Asia and the Pacific.

1

International and Regional Cooperation

Arenas of Peace

World peace has been a goal for millennia. The continents of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Europe are so vast that the most practical way to bring incessant warfare to an end would be to hope that small arenas of peace will be established and grow in size.

In a quantitative analysis, my study found that the most peaceful eras in world history have been unipolar—dominated by a single country (M.Haas 1970), though, of course, those dominated were usually unhappy. A multipolar world, according to the data, is the least peaceful. The level of conflict in a bipolar world, such as the Cold War division between Soviet and Western spheres of influence, falls between the unipolar and multipolar worlds.

World War II engulfed almost every corner of the globe. Afterward, bipolar Europe remained at relative peace. Asia was home to the most international conflicts, involving China, India-Pakistan, Indonesia, Korea, Vietnam, and various border conflicts. Yet, except for the ongoing war in Afghanistan and recent flare-ups on the Korean peninsula, Asia has enjoyed an almost continuous period of peace for the last two decades.

Although the island states of the Pacific remained calm since the battles of World War II, internal conflicts have recently erupted in Fiji, Papua, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. In all four cases, the conflicts have not spilled over to other countries.

There are several reasons why the zone of conflict in Asia has become an arena of peace similar to that in the Pacific. One of the most important is the rise of friendly relations among countries of both regions, as developed through intergovernmental cooperative arrangements. The present volume seeks to explain how and even why this has occurred.

The Rise of International Cooperation

There was a time when empires in the Americas (the Aztecs and the Incas), Asia (China and India), Europe (Rome), and the Middle East (Egypt and Persia) arose when one state could impose its domain over previously independent states. Dynastic rulers in China and India succeeded in creating unified empires where once there were warring states. Both efforts to unify Asia, which date back to 2,500 years ago, constitute major achievements in international statecraft (Bozeman 1960:Ch4; Grousset 1953; Spear 1960).

When no such dominance was possible within a geographic region, interimperial conflict prevailed. Rulers were considered “sovereigns” who could not be challenged. Cooperation among hegemony-seeking empires was not the norm.

With the rise of technological advances in warfare, prosperous countries acquired the means to resist imperial ambitions on the basis of various defense systems. One result in Europe was the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, an agreement to stop endless wars by accepting nation-states rather than rulers as sovereign, while ignoring whether their rulers required subjects to be Catholic or Protestant. Thus, the current states system developed when European countries and empires tired of endless warfare, decided to recognize states as the legitimate units of an international society, and promised not to interfere in the affairs of other countries. In other words, European powers sought an arena of peace.

But the most advanced European states then extended imperial control overseas to engulf the non-European world, stressing global rather than regional ambitions in a scramble for colonies that trampled on the sovereignty of non-European peoples. In time, those colonized resisted, starting in the Americas, whereupon Europe began to accept governments of the new states into the states system.

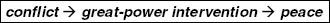

Proposals to unite warring European states into peacemaking arrangements appeared from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century, such as those of philosophers Dante, Immanuel Kant, and the duc de Sully. They consisted of pious plans for intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) of states to resolve conflicts short of war. After the Napoleonic Wars, the major powers met at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to reestablish the Westphalian acceptance of individual states within defined borders and an agreement to enforce that order with force after multilateral consultation among the great powers. The major powers, thus, took responsibility for assuring peace in Europe (see Figure 1.1). But the Vienna system of multistate cooperation broke down quickly because of conflict among the major powers.

Figure 1.1 Congress of Vienna model.

Simón de Bolívar’s concept of a federation of South American states led to a conference at Panamá in 1826. His objective was to promote the solidarity of the newly independent states of South America. The legacy of his effort is an array of cooperative, regional international organizations in Latin America, beginning with the Pan American Union of 1890, which set an example for other regions.

The calamity of World War I persuaded countries to establish a League of Nations in order to avoid future wars. But the United States refused to join the League, and colonized people were excluded because they lacked sovereignty.

After World War II, the United Nations emerged as an organization with nearly universal membership, committed to ending colonialism and thereby achieving universality. In 1949, the Council of Europe was formed, bringing Western European countries together, though countries in Eastern Europe did not join until the Cold War ended.

When large numbers of new states in Africa and Asia became independent, regional organizations of states formed in those regions. The island nations of the South Pacific are the latest to form regional bodies. The most, notable is the South Pacific Forum (SPF) in 1971, which changed its name to Pacific Islands Forum (the Forum) in 2000 as island states in the North Pacific joined the organization, emerging from the UN trusteeship system administered as a “strategic trust” by the United States.

Nowadays, the international arena consists of three main elements—individual countries organized as states, the United Nations and other IGOs, and such nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as Amnesty International that try to influence both states and IGOs. Some IGOs and NGOs have been universal in membership, but others have been specific to certain regions. Very few have been biregional or transregional.

What regional organizations have shared in common is the view that the League and the United Nations have encompassed too many countries for consensus to develop on matters of intimate importance among states within various geographic regions. For some countries, unwelcome domination by Western countries in the UN was reason enough to form separate regional bodies. Conflict was globalized during the Cold War, so some regions sought to uncouple themselves from East-West entanglements in order to establish an arena of peace.

When I embarked on a study of regional organizations in Asia during 1971 on behalf of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the UN Institute for Training and Research, one view at the UN New York headquarters was that regional organizations were disrupting the need to build a world community. The term “regionalism” was used, as if the formation of regional bodies was some form of ideological dissent from the universalism of the UN. After I submitted my report, published several years later (M.Haas 1979), the UN shifted perspective, realizing that regional organizations were building a regional spirit that was a precondition for the development of a true world community. Indeed, as my report had recommended, the UN began to provide assistance to regional organizations, and symbiosis between regional and universal organizations became the goal and the reality.

Asia was transformed from a zone of war into an arena of peace, thanks particularly to the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN).1 The Pacific islands region was fortunate to be at peace after World War II, and regional cooperation has ensured that the Pacific has not become a zone of interstate conflict.

Approaches to the Study of International Cooperation

Scholarship on regional international organizations initially consisted of accounts of the basic structure and purposes of regional arrangements, largely without overt theoretical considerations (M.Haas 1971:Part E). Descriptive accounts of particular organizations prevailed. When I wrote such an essay about the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (M.Haas 1974a) without employing a theoretical approach, the editor of a scholarly journal agreed to publish my work as a representative of an old-fashioned genre that needed to be respected, though the call for more theoretical research was increasing (M.Haas 1974b).

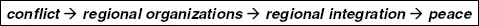

Figure 1.2 International organization model.

Pervading academic writing on international organizations for several decades was the view that nation-states are, at best, passé. Whether to promise greater security or to urge countries to seek peace, some scholars of international relations propounded the view that nations should abandon nationalism and band together for the human race to survive. Regional and universal organizations are often seen as realistic stepping stones toward a unified and peaceful world (see Figure 1.2).

Integration Theory

In The Uniting of Europe (1958), Ernst Haas saw the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) as a possible first step toward a world that might ultimately abolish the nation-state (cf. E. Haas 1974). In what is known as integration theory, Haas and others began to analyze how regional institutions might proceed toward the objective of political union (see Figure 1.3). ECSC, they argued, would begin to do so by having economic powers over governments, that is, by forming supranational regional entities.

The goal of ultimate political integration was presumed to be achievable through economic integration, that is, the abolition of trade barriers by such arrangements as customs unions, common markets, and free trade agreements. National sovereignty on economic matters was to be surrendered to a supranational authority. Consistent with their vision, there was a progression from ECSC to the European Economic Community and then to the European Community and finally to the European Union (EU). The goal of economic integration was advanced thereby. So persuasive was integration theory that the same perspective was applied to regional efforts outside Europe (E.Haas 1961; E.Haas and Schmitter 1964; E. Haas 1975; Nye 1971; cf. Schmitter 2005). Visionaries saw the process ultimately as a global effort that would bring about a peaceful world.

Figure 1.3 International integration model.

Political integration was assumed to result as states increasingly surrendered slivers of sovereignty. Yet political integration of sovereign states was not achieved. By the mid-1970s, Ernst Haas (1976) questioned whether a focus on political integration should continue. Soon, integration theory was all but abandoned.

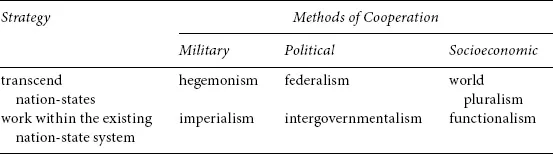

After all, how could a disunited world of sovereign states ever bring about a peaceful globe? Unpacking the assumptions of integration theorists and others, there are two main strategies—working within the existing nation-state system or transcending nation-states to establish a new type of international polity. The methods of achieving greater unity have stressed either military means, political negotiations, or socioeconomic penetration. Thus, there are at least six ways in which the world might become an arena of peace (see Table 1.1).

The hegemonism of a Rome and the imperialism of a Great Britain are inhumane and overly bloody pathways toward world unification. World War II proved that hegemonic methods are obsolete. The vulnerability of colonized peoples to be conquered by new hegemons also suggested that imperialism should be eliminated. Therefore, those in the quest for world peace considered four alternative approaches:

1. Federalists believe that separate political states must be unified. The federalist approach envisions the formal transfer of political authority to regional or global institutions and is a direct, constitutional attack on national sovereignty. The unification of the 13 American colonies, into a confederation and later a federation, is seen as the paradigm most appropriate at the international level, since peace might be maintained if a global authority had a monopoly on the use of force. Federalists espouse two tactical methods. Compact federalists urge world leaders to agree to a unified federal world through the “high politics” of diplomacy and international conferences to write a world constitution (Streit 1943; Hutchins 1948). Functional federalists would take one policy arena at a time, seeking to build up a federal supranational authority to deal with each issue-area, from agricultural policy to water policy, that is, on matters of “low politics” (Etzioni 1965; Friedrich 1968). Either way, the result would be a supranational entity with power over all previous states.

Table 1.1 Forms of international cooperation

Within Asia, a federal approach hardly seems realistic. The only example is the unification of sultanates under the Union of Ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I Theories

- Part II Dynamics

- Part III Effectiveness

- Notes

- References

- Index