eBook - ePub

Managing Risks in the European Periphery Debt Crisis

Lessons from the Trade-off between Economics, Politics and the Financial Markets

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Risks in the European Periphery Debt Crisis

Lessons from the Trade-off between Economics, Politics and the Financial Markets

About this book

The European Periphery Debt Crisis (EPDC) has its roots in the structural characteristics of the individual economies affected. This book offers a full diagnosis of the EPDC, its association to the national and international structural characteristics and a full analysis from a risk management point of view of the available policy options.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Risks in the European Periphery Debt Crisis by G. Christodoulakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Risk Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Genesis of the Crisis, Use and Abuse of Economic Policies

1 |  | The Genesis of the Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis |

Philippe d’Arvisenet |

1 Introduction

The euro crisis is often said to have been the consequence of an excessive debt, private or public, and finally both. But that excessive debt would not have resulted in such a serious crisis had the eurozone institutions properly ensured the correct working of the mechanisms of a monetary union.

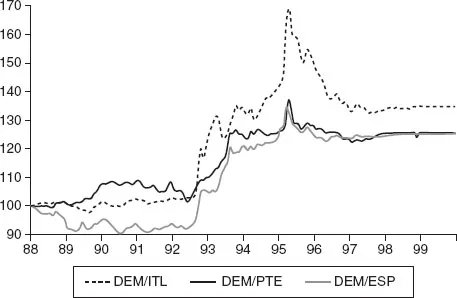

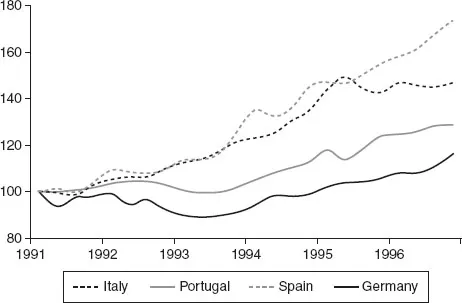

The euro was seen as instrumental in eliminating the risk of competitive devaluations and possible protectionist pressures, obviously something that would not be welcome in a deep integrated single market with freedom of trade in goods and services and capital movements. History shows that European countries have repeatedly shown little appetite for floating exchange rates. Following the collapse of Bretton Woods, they launched the “snake”, then the European monetary system (EMS), a regime of fixed but adjustable exchange rates. When the EMS collapsed in the early 1990s, with huge exchange rate adjustments (Figure 1.1), considerable changes in exports performances followed (Figure 1.2). Beside political considerations, such disturbances were a good argument in favour of a single currency, a much more robust arrangement than a classic fixed exchange rate regime.

When the euro was launched, it did not comply with the requirements of an optimal currency area. Some suggested that the features of an optimal currency area that justify the adoption of a monetary union would progressively show up (the so-called “endogenous currency area theory”). Until the crisis burst, the cycles became more correlated, as we document below (regarding the rates of growth, inflation, output gaps, etc), but simultaneously, labour costs diverged, and rates of indebtedness were not kept under control, resulting in a widening of external imbalances. The conjunction of high debt together with the rise in risk aversion resulted in “sudden stops”; the appetite of investors to finance external and public deficits disappeared, and the crisis erupted. In a true monetary union that would not have happened, the deficits being automatically financed; the euro eliminated exchange rate speculation, but not speculation in debt. Things happened just as if member countries had issued debt in a foreign currency without control over their own currency by a central bank that could act as a lender of last resort. Official support, together with policies aiming at reducing imbalance became inevitable.

Figure 1.1 Exchange rates

Figure 1.2 Exports of G & S, volume (index Q1/1991 = 100)

Sources: Eurostats, OECD

At the beginning of the crisis, policies that were implemented aimed at reducing fiscal deficits with the implementation of austerity programs, on a case-by-case basis. Delays and errors were made with respect to the distinction between liquidity and solvency, the involvement of the private sector, and the size and scope of the bailout mechanisms. With the worsening of the crisis, contagion and policy mistakes triggered a vicious circle between sovereign risks and banking risks. It became obvious that pan-European measures were required, hence the European semester, the six pact, the two pact, the “fiscal compact”) and the banking union (d’Arvisenet, 2012).

Beyond that, it can been stressed that in a monetary union with no exchange rate risks, countries/ regions tend to specialize in activities in which they benefit from comparative advantages. That is welfare-enhancing, but does not come without side effects. Some will specialize in the production of tradables – industry in the first place; others will specialize in non tradables (services). As a consequence some will exhibit structural foreign trade surpluses, and others structural deficits. Such external imbalances are not the consequence of mistakes in policies; they result from the natural mechanism of comparative advantages. Ruling out such imbalances, in other words refusing structural transfers similar to those that take place in any country/ federation, assumes that restrictive policies are conducted repeatedly in countries that tend to exhibit deficits. The alternative would be a limit on the mechanism of specialization. One might then question the advantages of adopting a common currency.

2 Without fiscal federalism, excess debt and widened external imbalances triggered a sudden stop

2.1 Rising imbalances

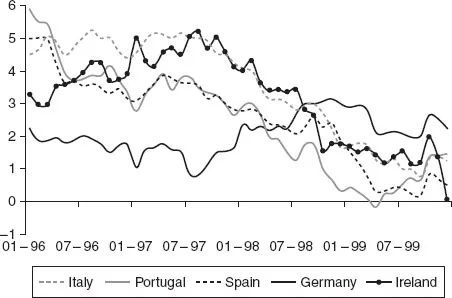

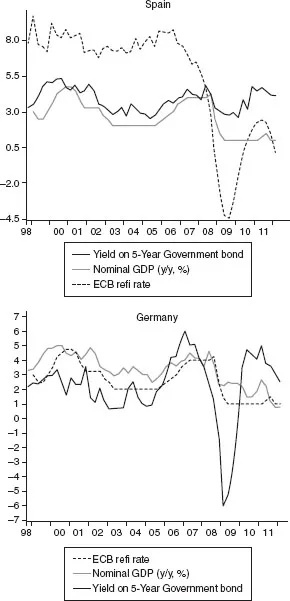

The key objective of monetary policy, that is avoiding inflation (or deflation), can be achieved through the reputation of the central bank, backed by its independence and its transparency. When its reputation is solidly established, and the rate of inflation moves above or below the central bank’s inflation target, such developments are seen as temporary and do not affect expectations, a key driver of inflation in the medium term. When its reputation is absent, however, building it requires an investment that is costly in terms of growth and jobs (the Volcker experience). In the eurozone, the central bank’s reputation was simply transferred from the Bundesbank to the ECB, all countries enjoyed low short- and long-term rates as a result, and real rates dropped to lower levels (Figure 1.3).

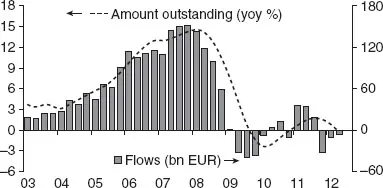

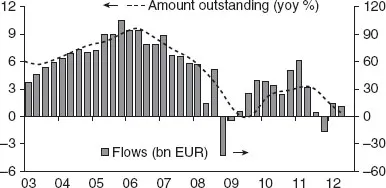

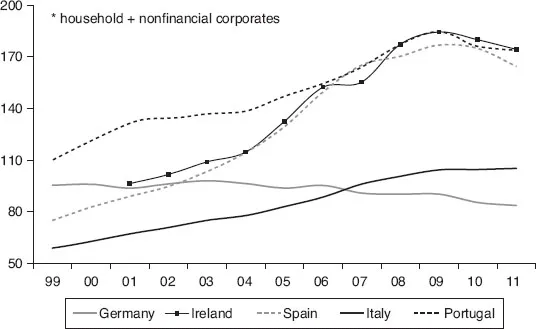

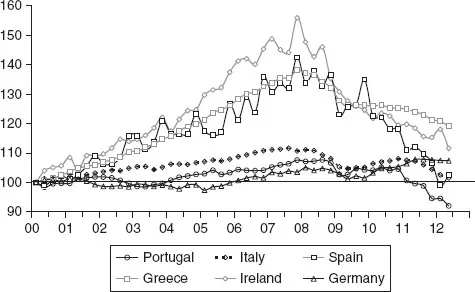

Countries that had previously experienced high interest rates benefited from much friendlier financing conditions with real rates much below growth, especially in the south of Europe. By contrast, financial conditions in Germany were restrictive (Figure 1.4). So a borrowing binge erupted (Figures 1.5 and 1.6). This resulted in elevated debt ratios, especially in the private sector (Figure 1.7), where domestic demand was strengthened (Figure 1.8).

These conditions, which favoured certain sectors above others, led to a misallocation of resources (particularly in residential construction), fuelling a bubble rather than the development of the tradables sector. In Spain and Ireland, for example, employment in construction as a proportion of total employment rose to twice its long-term average. In other countries, most notably Greece, capital inflows helped finance government spending (starting with current expenditure). For some time, this gave no apparent cause for concern, as shown by the extremely low levels of sovereign spreads. Growth was boosted well above potential and above real rates, which supported the appetite for debt and risk, with finally adverse consequences for both relative rates of inflation and competitiveness. The consequences were a slowdown in exports and soaring imports driven by strong domestic demand. In turn, this led to a widening of external deficits.

Figure 1.3 Real three-month interbank rates, %

Sources: Thomson Reuters, BNP Paribas

The boom in activity and asset prices inflated the tax base (Ireland, Spain), so the fiscal situation appeared sound. External deficits resulting from a private sector financing gap or from widened fiscal deficits were easy to finance. Capital flows were (rightly) expected to grow with the expansion of trade and financial transactions resulting from the single market in a context where exchange rate risks had disappeared. In fact, the eurozone seemed to behave as an optimal currency area, which it was not.

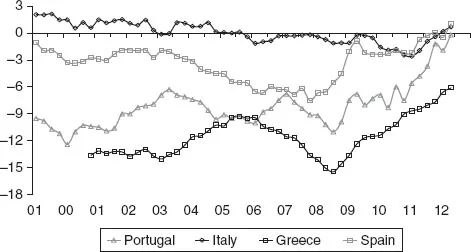

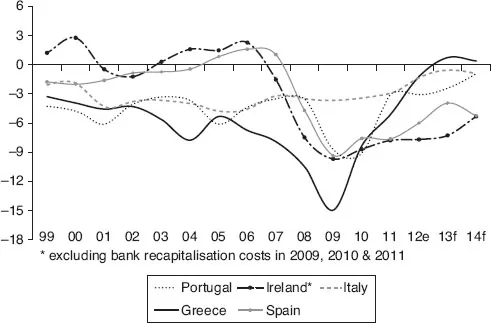

The widening of external deficits (Figure 1.9) and expansionary fiscal policies in some “peripheral” ’ countries (Figure 1.10) continued for as long as investors had an appetite to lend (Figure 1.11). That might not have been an issue had the deficits been related to productive investment that would have generated income in the future. But in the case of many countries, the deficits were due to increasing government expenditure and/or excesses in the private sector, especially in residential construction.

Figure 1.4 Financial conditions in Germany

Figure 1.5 Eurozone: credit to non financial corporate

Source: BCE.

Figure 1.6 Eurozone: credit to households

Source: BCE.

Figure 1.7 Debt of the private sector * as % of GDP

Sources: Eurostat, BNP Paribas.

Figure 1.8 Domestic demand volume, Indice Q1/2000=100

Source: Eurostat

Figure 1.9 Goods and services balance, % of GDP

Sources: Nationales

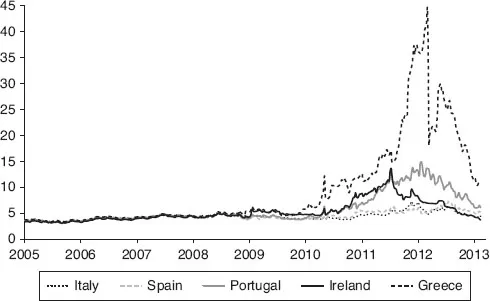

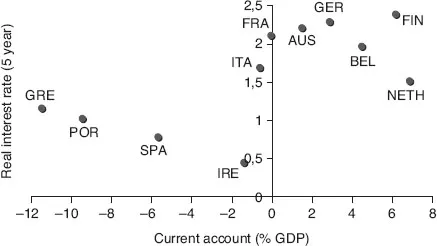

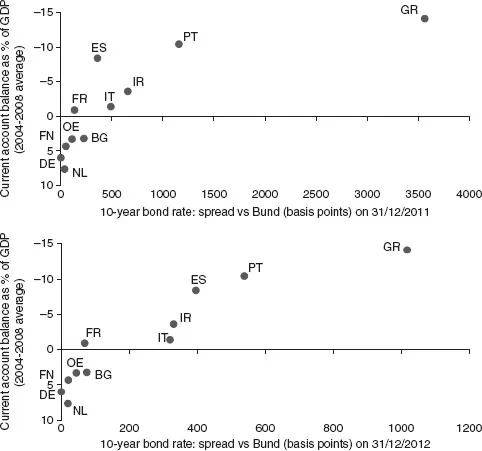

Finally, access to external finance became a problem. Countries that experienced low real rates exhibited large current account deficits (Figure 1.12). When the crisis erupted, countries with a large current account deficit were then affected by high spreads (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.10 Structural budget balance as % of GDP

Source: European Comission (Ameco)

Figure 1.11 Ten-year government bond yield, %

Source: Thomsan Reuters

Figure 1.12 Real interest rate and external imbalances

Source: European, BNP Paribs

Figure 1.13 Current account balance as % of GDP

Source: European Comission(Ameco), Thomsom Reuters

2.2 Sudden stops, spreads, fundamentals and beyond

Debt is unfriendly to growth. Herndorn et al. (2013) have shown that over 1945–2009, advanced countries with a government debt to GDP above 90% experienced an average rate of growth of 2.2% against 3.2% with a ratio between 60% and 90%. During the period often referred to as the “great moderation”, when inflation, unemployment and interest rates were all low, and demand for credit was stimulated by favourable financial conditions and a lack of volatility in economic activity, it became clear that external imbalances had to be reduced. According to conventional wisdom, that can be addressed with an effort to boost competitiveness and reduce fiscal imbalances and therefore domestic demand. That is a challenge in countries where foreign trade elasticities are such that an internal devaluation is not an easy solution.

Until the financial crisis broke in the late 2000s, almost all analysis of economic policy (BIS research was a conspicuous exception) attached little importance to trends in debt and credit. The health of the economy was supposed to be guaranteed by an independent central bank aiming at price stability by using its policy rate. Debt was considered – rightly, up to a point – as a means of improving the allocation of resources. It helps households smooth their consumption over bumpy income streams, and companies to insulate their investment and activity from fluctuations in demand. Similarly, government debt helps to spread taxes and consumption between generations: if one assumes that future generations will be richer and more populous, with more human capital and more efficient productive capacity, they can finance a transfer to the present generation. Inter-temporal utility is thereby increased. But beyond a certain level, debt has negative effects. Higher interest costs reduce the ability to cope with shocks, and increase sensitivity to variations in activity and interest rates, and solvency can be affected. As far as governments are concerned, the scope to bolster activity or assist economic agents in difficulty is reduced. Economic activity weakens and becomes more volatile.

Budget adjustments alone would undoubtedly suffice if spreads depended solely on fundamentals. Since 2008, however, as we have seen, panic behaviour has driven spreads well above the levels justified by fundamentals alone. This justifi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I: Genesis of the Crisis, Use and Abuse of Economic Policies

- Part II: Crisis Resolution, Prospect and Retrospect

- Index