eBook - ePub

The Unhappy Divorce of Sociology and Psychoanalysis

Diverse Perspectives on the Psychosocial

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Unhappy Divorce of Sociology and Psychoanalysis

Diverse Perspectives on the Psychosocial

About this book

A collection of 18 contributions by well-known scholars in and outside the US, The Unhappy Divorce of Sociology and Psychoanalysis shows how sociology has much to gain from incorporating rather than overlooking or marginalizing psychoanalysis and psychosocial approaches to a wide range of social topics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Unhappy Divorce of Sociology and Psychoanalysis by Lynn Chancer,John Andrews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Personality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The History of Sociology and

Psychoanalysis in the United

States: Diverse Perspectives on a

Longstanding Relationship

1

Opening/Closing the Sociological Mind to Psychoanalysis

George Cavalletto and Catherine Silver

For sociologists interested in integrating psychoanalytic ideas and concepts in their work, important lessons, both positive and negative, can be gleaned from the past history of the relationship between the social sciences and psychoanalysis. Specifically, regarding US sociology, one period is arguably of particular interest: the period following World War II, from the late 1940s through the 1950s.

Evidence from these years suggests that the influence of psychoanalytic ideas was extraordinarily widespread among American intellectuals. Reflecting on the period, Peter Berger reports that psychoanalytic ideas about the unconscious, repression, and the centrality of sexuality and childhood played a significant role in the “world-taken-for-granted” of college-educated Americans (Berger, 1965, pp. 26, 28). American sociologists of the period, the evidence suggests, shared in this attachment to psychoanalytic ideas. According to a survey of the major fields of sociology written in conjunction with the American Sociological Society’s 1954 annual meeting, “the theories of Sigmund Freud have become pervasive in American thought-ways in the mid-twentieth century and in contemporary American sociology. Many sociologists are using adaptations of psychoanalytic methods, segments of its theories, and . . . selected and varied concepts” (Hinkle, 1957, p. 574). Contained in the reflections of another sociologist writing during the period, we find stated that “an awareness of psychoanalysis has tended to become a normal quality in an American social scientist” (Madge, 1962, p. 565). And Howard Kaye, in an astute overview of the period, retrospectively came to a similar conclusion: “In the 1950s and 1960s, Freudian theory was deemed to be a vital part of the sociological tradition. . . . Freud was very much an object of admiration and discipleship in Western academic and cultural circles” (1991, p. 87).

This essay examines several aspects of this “opening” of the sociological mind to psychoanalysis. First, we present statistical evidence to support the reportorial and anecdotal accounts above. We continue with a detailed analysis of various articles and book reviews dealing with psychoanalysis published in the late 1940s and the 1950s in the professional journals considered at mid-century to be dominant in the field: the American Journal of Sociology (AJS) and American Sociological Review (ASR) (Parsons and Barber, 1948, p. 250; Kinloch, 1988, p. 181). The main findings of these examinations will then be placed within the historical record of major institutional and ideological changes that affected academic sociology in the period, with the goal of providing not only evidence of an upsurge of a positive interest in psychoanalytic ideas but also an explanation of why there arose a sociological backlash against the use of these ideas and why it proved so effective. For as we shall see, this backlash was of such ferocity that by the end of the 1950s the newly “opened” sociological mind had become for the most part “closed.”

Preliminary data

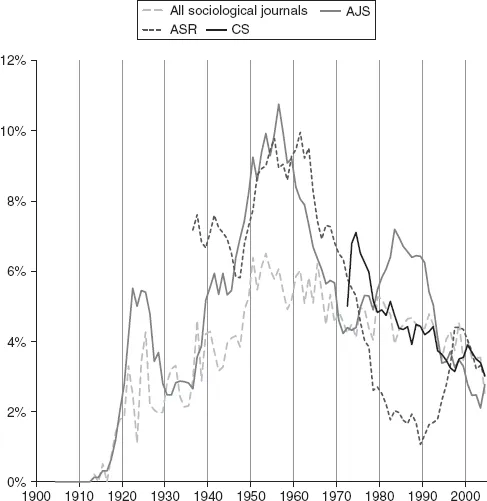

Figure 1.1 covers the period 1900–2005 and indicates graphically the percentage of articles and book reviews using terms that refer to psychoanalysis, first in all sociological journals (the dotted line) and secondly in AJS and ASR (the thin line, and the line made up of dashes). The percentage figures reflect the proportion of all articles and book reviews published in each year that contain one or more terms from a list of terms related to psychoanalysis. As the graph makes clear, beginning in the mid-1910s, the percentage of articles and book reviews that contained one or more of these terms rose decade by decade and peaked in the mid-1950s, only to decline at first gradually and then, by the mid-1960s, precipitously, eventually falling by 2005 to a level comparable to that of 1920. Most notably, the graph makes evident that with regard to AJS and ASR, the proportion of articles and book reviews referencing psychoanalysis in the early 1950s exceeded 10 per cent while the proportion in the earliest and most recent decades hovered during most years around 2 per cent.

Readers will notice that several abrupt upsurges occurred in the years before and after the 1950s, the most significant one being in the late 1930s. The abruptness of this earlier rise reflects, in part, a response to the death of Sigmund Freud in 1939 and it had a quite different character than the one that peaked in the 1950s—for one thing, almost all of the authors of the articles published in the earlier period were non-sociologists (Jones, 1974, p. 32), whereas (as we shall see in the next section) all but two of the articles of the 1950s were written by sociologists. Readers will also notice that Figure 1.1 indicates several instances of sharp declines in psychoanalytic references, most conspicuously ASR’s abrupt and deep drop-off in the early 1970s. This particular decline was the direct result of the journal’s elimination of its book review section and the launching in its place of a new publication devoted solely to book reviews, Contemporary Sociology (CS). That such a steep decline in references resulted not from changes in the journal’s article section but rather from the elimination of its book review section and—equally important—that the percentage figures of the new book review journal were immediately higher than those of ASR, both strongly suggest what the analysis below confirms: in the years preceding its elimination, ASR’s book review section accounted for a majority of this journal’s items referencing psychoanalysis, a finding also repeated in the case of AJS.

Figure 1.1 Sociological journal articles and book reviews with references to psychoanalysis, 1900–2004

Source: Data compiled from Sandbox, a beta search program of JSTOR. Lines represent percentages of items (articles, reviews) out of total items of each year that contain one or more of the following terms: Freud, Freudian, psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic, Horney, Lacan.

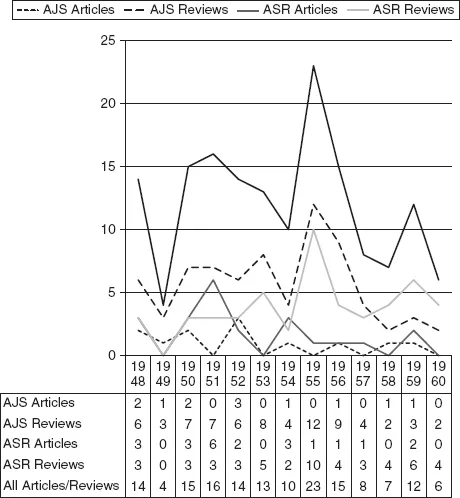

Figure 1.2 focuses on a narrower time period than Figure 1.1: the period 1948–1960, and indicates the number of articles and book reviews with a significant focus on psychoanalysis. These numbers are considerably smaller than those represented in percentage terms in Figure 1.1. The smaller numbers reflect the fact that when all the articles and book reviews pinpointed by the computerized search that yielded the figures of Figure 1.1 were directly examined, more than half of them did not include any significant discussion of psychoanalysis.

Figure 1.2 Articles and book reviews with a significant focus on psychoanalysis, American Sociological Review and American Journal of Sociology, 1948–1960

Also, Figure 1.2 confirms as a general principle what Figure 1.1 presented as a consequence of ASR’s elimination of book reviews in 1972: both journals’ book review sections were more open to a discussion of psychoanalytic ideas than were their article sections (that is, book reviews constituted 87 per cent of all items dealing significantly with psychoanalysis in AJS and 68 per cent of such pieces in ASR). Other types of variations are also revealed by the table and graph of Figure 1.2: for one thing, more articles and book reviews with a significant focus on psychoanalysis were published in the first six years of the period 1948–1960 than in the last six years (this was especially true of articles, with 72 per cent of all such articles appearing in the first six years). Moreover, Figure 1.2 reveals major differences between the two journals’ article and book review sections: in particular, the Figure’s table shows that AJS published significantly fewer psychoanalytically focused articles than ASR (AJS: twelve articles; ASR: twenty-two articles), while at the same time AJS published significantly more psychoanalytically focused book reviews than ASR (AJS: seventy-three book reviews; ASR: forty-nine book reviews).

This in turn suggests that to gain a better understanding of the quality and range of these journals’ opening to psychoanalysis, their writings’ actual contents need to be examined. From this examination, we should be able to uncover reasons behind differences in the writings of the first and last years of the period, and between the two journals’ handling of psychoanalytic issues; we should also be able to gain general insight into differences between those who favored and those who opposed the opening to psychoanalysis.

Analysis of articles and book reviews

The article sections of AJS and ASR

Articles positively disposed toward psychoanalysis

Several basic facts emerge from an overview of the articles from 1948–1960 in AJS and ASR that contain a significant focus on psychoanalysis. Overall, thirty-four articles with this focus appear in the two journals, a much higher proportion (65 per cent) in ASR than in AJS. Of all the articles published during the period, twenty-three (68 per cent) were deemed positively disposed toward psychoanalysis and the use of psychoanalytic ideas in sociology. Of articles positively disposed to psychoanalysis versus ones judged negatively disposed, the records of AJS and ASR are diametrically opposed: the 1948–1960 issues of AJS contained only four positive articles (out of the journal’s twelve psychoanalytically focused articles); on the other hand, ASR contained 19 positive articles (out of twenty-two in total).

When the positive and negative articles from both journals are considered together, one discovers another distinction dividing them into two groups. Each group is characterized by a distinct style of sociological journal writing. One group is written in an essayist style, a broad category that includes observational description and the refinement of interpretation, the review of alternative ideas and an engagement in general theorizing. A second group of articles is written in a scientistic style, a narrower category that includes a concern with hypothesis formation, the operationalization of concepts and statistical analysis of data. In some ways, this stylistic difference points to factors involved in the methodological distinction between qualitative and quantitative research methods, although “essayist” clearly refers to a broader category than “qualitative,” while “scientistic” is quite close to

“quantitative.” (Moreover, beyond its reference to a specific regard for quantitative methods, “scientistic” also brings with it an allusion to the various ways that its adherents often make manifest a conviction that quantitative methods constitute the only source of genuine factual knowledge, whether that be of nature or of human society, thereby, along with restricting “science” to quantitative methods, idealizing it as well (Habermas, 1971, pp. 4–5). When considered in terms of the articles that were positively disposed toward psychoanalysis, this divide has a distinctly chronological aspect: of the articles favoring the use of psychoanalytic ideas, all those of an essayist style were published before 1953; although several of a scientistic style were also published before 1953, only those of this style were published after 1953.

The most significant articles of the essayist type—two essays of general theorizing—appear at the beginning of the period: both by Talcott Parsons. In the first, published in the January 1948 issue of AJS, Parsons begins by expressing concern about the insecure academic status of sociology and in particular the discipline’s perceived inferiority in comparison with the more mature and theoretically integrated social science of economics. It is in this context that Parsons announces his championship of “a new synthesis” that would allow sociology to reach “full maturity.” Explicitly modeling his ideas here on the integration of disciplines that he had institutionally achieved at Harvard with the setting up of the Department of Social Relations in 1946, Parsons posits as sociology’s goal the creation of a master general theory that would combine concepts of sociology, anthropology and a Freudian-influenced social psychology. This unified theory, Parsons asserts, would draw much from Freud, who should be placed alongside Durkheim and Weber at the head of the sociological canon. Sociologists, Parsons adds, need also to examine the ideas of the neo-Freudians, for along with Freudian theory, “their work is a major contribution toward the synthesis which must develop if sociology is to come to full maturity” (Parsons and Barber, 1948, pp. 247, 252, 253).

In his second article, published in ASR in 1950 (and a transcript of his presidential address at the 1949 annual meeting of the American Sociological Society), Parsons vigorously reiterates his belief in the importance of creating for the social sciences “a general system of theory.” By this, he meant a theory that would serve these sciences in the way that theoretical physics serves varied scientific investigations of the properties of matter and energy. Foreshadowing ideas that would shortly appear in Toward a General Theory of Action (1951), Parsons calls for a theoretical “synthesis of sociology with parts of psychology and anthropology” and he devotes particular attention to what he sees as a breakthrough in establishing a theoretical common ground by which to connect theories of “the personality structure on the psychological level with the sociological analysis of social structure” (1950, pp. 8, 9). With the understanding that the psychology of which he speaks incorporates psychoanalysis, Parsons advances the claim that in the work of connecting psychological and sociological theories,

great progress has been made. The kind of impasse where ‘psychology is psychology’ and ‘sociology is sociology’ and ‘never the twain shall meet,’ which was a far from uncommon feeling in the early stages of my career, has almost evaporated. There is a rapidly increasing and broadening area of mutual supplementation. (p. 9)

Echoes of Parsons’ espousal of a sociological opening to psychoanalysis can be found in journal articles published in the early years of the period though most frequently this is advanced from a perspective of a specialized sociological subfield rather than that of cross-disciplinary theory formation. Typical in this regard are articles by Ernest and Harriet Mowrer who, beginning in the 1920s, associated themselves with a notable group of social workers, psychiatrists, and sociologists to create a psychoanalytically informed subfield of family studies (LaRossa and Wolf, 1985, p. 534; Hinkle, 1957, p. 593). In a 1951 ASR article, the Mowrers devote much of their attention to a discussion of the various ways that their sociological subfield is grounded on the reconfiguration of the Freudian “sex instinct” into “a more complex series of socially derived motivational units” (p. 28), thereby allowing “the family social psychologist [to] utilize a number of the theories and concepts of psychoanalysis, but structured by a cultural context and implemented by role analysis in the dynamics of marriage...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: The Unhappy Divorce: From Marginalization to Revitalization

- Part I The History of Sociology and Psychoanalysis in the United States: Diverse Perspectives on a Longstanding Relationship

- Part II Are Psychosocial/Socioanalytic Syntheses Possible?

- Part III The Unfulfilled Promise of Psychoanalysis and Sociological Theory

- Part IV The Psychosocial (Analytic) In Research and Practice

- Index