- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How and why do business organisations contribute to climate change governance? The contributors' findings on South Africa, Kenya and Germany demonstrate that business contributions to the mitigation and adaptation to climate change vary significantly.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Business and Climate Change Governance by T. Börzel, R. Hamann, T. Börzel,R. Hamann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Business Contributions to Climate Change Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction

Ralph Hamann and Tanja A. Börzel

Introducing our research question

Climate change and related social and environmental changes present societies with increasingly urgent problems at multiple spatial scales. A diverse range of social actors is involved in contributing to climate change, and an even broader range is suffering and will suffer its manifold consequences. In this book we focus on business organisations because they are vital arenas of decision-making, in both mitigation and adaptation. In other words, they are important sources of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), and they therefore need to help to mitigate these emissions. At the same time, these businesses also need to make significant changes to prepare for and adapt to increasingly severe climate change and the resulting socio-economic changes (Berkhout et al., 2006; Kolk and Pinkse, 2012).

We ask how and why business organisations contribute to climate change governance. Governance is broadly about ‘organised efforts to manage the course of events in a social system’ (Burris et al., 2008: 3). We define it here more specifically as the structures and processes through which commonly binding rules are established, and through which public goods or services are provided (Risse, 2011). Climate change governance, then, pertains first to those efforts that seek to maintain a stable climate as an essential, global public good – including the norms, rules and procedures that aim to mitigate climate change through reduction of atmospheric greenhouse gases, through either reduced emissions or sequestration. Second, climate change governance seeks to ensure that social and economic systems are able to adapt, and effectively respond, to climate changes that are already occurring and that will occur in future. This is commonly referred to as climate change adaptation (IPCC, 2007). To some extent, mitigation and adaptation are distinctive policy arenas, because ‘their impact refers to different temporal and spatial scales [… and they] involve different actors in the process of policy formulation and implementation’ (Pinkse and Kolk, 2012: 181). But in some areas, notably land use change and forests, there are important synergies between adaptation and mitigation (e.g. Swart et al., 2003).

The focus on business contributions to climate change governance links this book to a broader debate about the role of private actors in governance, and one of our objectives is to synthesise the partially separate manifestations of these themes in the political science and management studies literatures. The role of private actors in governance is still contested. In an increasingly globalised economy, companies are assumed to escape strict national regulation by relocating their production sites to ‘areas of limited statehood’ where state regulation is low and/or enforcement is weak. While countries with high levels of regulation will respond by lowering their standards, countries with weak regulatory capacities refrain from tightening regulation in order not to lose foreign direct investment. Thus, the behaviour of firms can drive states into a ‘race to the bottom’, leading to degradation of natural resources and to compromising social standards for the sake of potential economic growth or attracting short-term foreign investment (see, e.g. Chan and Ross, 2003; Brühl et al., 2001; Kaufmann and Segura-Ubiergo, 2001; Lofdahl, 2002). At the same time, however, companies can be ‘drawn into playing public roles to compensate for governance gaps and governance failures at global and national levels’ (Ruggie, 2004a: 13). Empirical evidence suggests that under some conditions companies voluntarily commit themselves to social and environmental standards and adopt private self-regulatory regimes – even in the absence of a regulatory threat by the state (e.g. Mol, 2001; Vogel and Kagan, 2004; Levy and Newell, 2002; Pinkse and Kolk, 2009; Prakash and Potoski, 2007; Greenhill et al., 2009; Börzel and Thauer, 2013). Climate change is a formidable research area in which to investigate whether business performs such governance functions, what forms these contributions take, and under what conditions and for which motives and incentives business performs them.

This introductory chapter provides an initial review of the literature and a conceptual framework for the book as a whole. In the next section, we explain in more detail what we consider to be business contributions to climate change governance. We then discuss the issue of climate change as a ‘wicked problem’ in order to describe the problem characteristics and organisational field of interest in our empirical analyses. We also explain our focus on ‘areas of limited statehood’, defined as geographical or thematic areas in which states struggle or even fail to establish and enforce commonly binding rules and to provide or safeguard public goods. The concept of limited statehood helps us first, to investigate climate change as an organisational field in which states face fundamental challenges, and second, to analyse business contributions to governance in particular geographical areas, in which states face capacity constraints.

In the fourth section, we develop a framework with which to characterise firm responses to climate change and to address the first question of this book: how do companies contribute to climate change governance? We develop this framework by combining existing typologies in either climate change mitigation or adaptation, and use it to provide an overview of the business activities discussed in the chapters of this book. Finally, in the fifth section, we consider a set of concepts to help answer the second question of this book: why do companies contribute to climate change governance, and what explains the variance in firms’ responses? These concepts fit broadly into three categories – institutional drivers, organisational drivers and problem characteristics – and their relative importance and potential interaction will be prominent themes in the empirical analyses and concluding chapter of this book.

Business contributions to climate change governance

Almost by definition, much of the governance literature emphasises the role of either public or private regulation in curbing the negative externalities associated with private organisations’ activities. This is a vital concern, given the growing emissions of greenhouse gases, most of which are attributable to business organisations. Climate change that is brought about as an external consequence of emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels and fugitive emissions from smokestacks, exhausts, refrigerators and various other business processes has thus been framed as a large-scale market failure by prominent government advisor, Nicholas Stern:

The problem of climate change involves a fundamental failure of markets: those who damage others by emitting greenhouse gases generally do not pay … Climate change is a result of the greatest market failure the world has seen.1

The market failure is at the same time a governance failure, due to the absence of binding rules and ongoing difficulties in establishing and enforcing these rules in the international climate change regime. This is why establishing and enforcing binding rules is a vital part of our definition of climate change governance, and why we want to understand better how and why companies respond to such rules and sometimes even contribute to their development, even if states are reluctant or incapable to do so.

At the same time, companies are increasingly expected not just to adopt commonly binding rules, but also to develop innovative business processes, products and services that help society reduce emissions and/or adapt to climate change. Such contributions to the delivery of public goods associated with climate stability or social resilience may be motivated by the need to build companies’ competitive advantage and to establish and maintain a conducive business context (Porter and Kramer, 2011; Börzel and Thauer, 2013). Indeed, such hopes and expectations are expressed even at the highest levels of the United Nations climate change machinery, as illustrated in the following comments made by Christiana Figueres (Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) to a meeting of business leaders:

Business has the power to change consumer and supplier behaviour and turn it into a powerful vocal support that gives policy makers a clearer space in which to act … Admittedly, in the absence of a clear solid international framework, this represents a risk for business, but I pose that it is a manageable risk … Your [business] leadership is essential: 1. To push the envelope within your own business; 2. To bring around others in your business field to be ambitious; and 3. To create a virtuous cycle of push and pull between public and private sectors to pave the road toward sustainability and a low carbon future.2

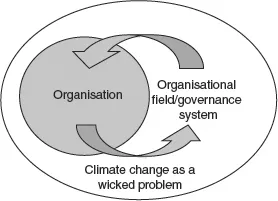

This ‘push and pull between public and private sectors’, illustrated in Figure 1.1, is a prominent theme in this book. Climate change has created an issue-specific organisational field, a platform for ‘debates in which competing interests negotiate over issue interpretation’ (Hoffman, 1999: 353), in which institutions create a set of expectations to be fulfilled or options from which to choose (Hoffman, 2001). Climate change has led to widespread and diverse changes in regulative, normative and cognitive institutions, and these exert pressure on companies to respond. For example, while state-based rules on climate change in Africa are as yet relatively limited, initiatives such as the Global Reporting Initiative or the Carbon Disclosure Project have created an important set of normative and cognitive structures.3 We thus expect a variety of institutional factors to drive firms to engage in activities related to climate change mitigation or adaptation. These institutional drivers are complemented or enhanced by firm-internal drivers, such as expected efficiency gains or increased market share, or benefits for a firm’s reputation. Organisations are not just passive respondents to institutional forces, but have diverse interests and display some urgency in responding within their context (DiMaggio, 1991; Perrow, 1985). Companies’ characteristics and strategic orientation are likely to influence how they respond to institutional pressures or incentives. In particular, management scholars have highlighted the diverse ways in which firms may seek to enhance their competitiveness in response to environmental concerns. This interplay between companies and their institutional context in influencing firms’ responses – the top arrow in Figure 1.1 – is discussed in more detail in a dedicated section below.

Companies’ responses will inadvertently, or even purposefully, influence the organisational field in which they are active – that is, there is likely to be some influence such as that represented by the bottom arrow in Figure 1.1. Some organisations may make a strategic choice to become institutional entrepreneurs – ‘actors who have an interest in particular institutional arrangements and who leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ones’ (Maguire et al., 2004: 657). The organisational field surrounding climate change is an emerging one, especially in areas of limited statehood. Given, also, the significant business interests at stake in the climate change policy arena (such as the imposition of carbon taxes, for example), there are important incentives for companies to try to influence the organisational field proactively. This is likely to include lobbying to achieve particularistic interests, which of course has already received significant scholarly attention (Ikwue and Skea, 1994; Kolk, 2001; Levy, 1997, Newell and Paterson, 1998). According to some analyses, such overtly confrontational approaches have shifted toward more conciliatory or even cooperative forms of engagement with the public sector (Kolk, 2001; Levy and Kolk, 2002; Levy and Newell, 2002; Levy and Rothenberg, 2002). The bottom arrow in Figure 1.1 may even include proactive efforts by firms to raise anti-pollution standards in public policy, or support the implementation of such regulations, for reasons discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the interactions between organisations and the governance system

We take a broad approach to climate change governance that includes activities within firm boundaries, as long as they are intentional and have some benefits for climate change mitigation and/or ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Business Contributions to Climate Change Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood: In-troduction

- 2 Corporate Response to Climate Change in Areas of Limited Statehood: An Outline of the Organisational Configurations in Kenya and South Africa

- 3 Climate Change Policies in the Car Industry: Asset Specificity as a Driver of Internal Innovation

- 4 Renewable Energy Incentives across Varying Levels of Statehood

- 5 Voluntary Collective Commitment: The Case of Business and Energy Efficiency in South Africa

- 6 Business Contributions to Climate Change Adaptation – From Coping to Transformation? Insights from South Africa and Germany

- 7 Adaptation to Climate Change: An Investigation into Woolworths’ Water Management Measures

- 8 Insurance, Climate-Risk and the Barriers to Change

- 9 Of Culture and Religion: Insurance Regulation and the Informal Economy in a South African City

- 10 Business and Climate Change Governance: Conclusions

- Index